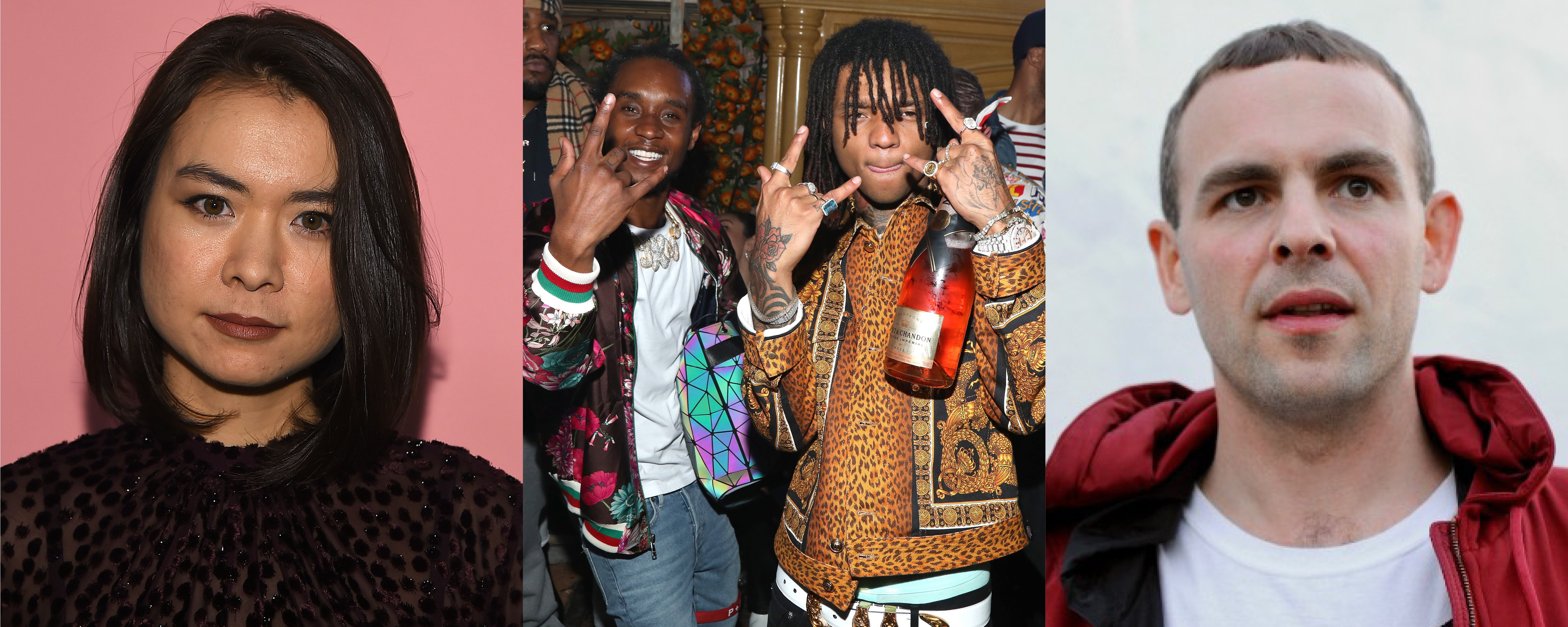

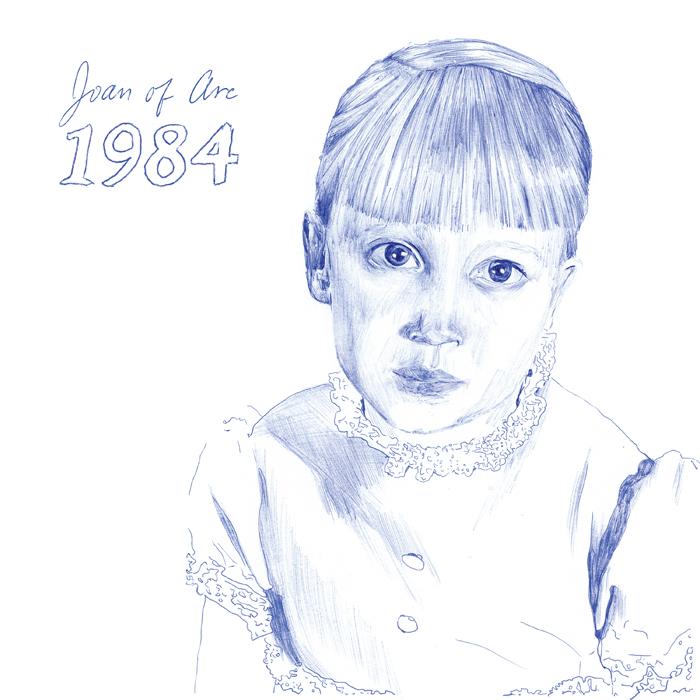

Experiments are controlled and reproducible, which is why Joan of Arc were always more of an art band. For the last 25 years, the interchangeable crew of musicians comprising frontman Tim Kinsella’s Chicago-based collective have produced more than 20 adventurous full-lengths, most featuring Kinsella on lead vocals. On their latest, they’ve toppled even that sort-of constant: The entirety of 1984 is written and sung by the newest member of Joan of Arc, Melina Ausikaitis, a solo and visual artist who’s played with the group for roughly five years and sang backup on last January’s He’s Got The Whole Land This Land Is Your Land in His Hands. It is first of all a vocal album, characterized by Ausikaitis’s idiosyncratic voice, while behind her the rest of the group (Kinsella, Theo Katsaounis, Bobby Burg, and Jeremy Boyle) assemble drone hums, improvisational melodies, field recordings, and empty space into an intimate and strangely intense piece of emotional landscape.

What 1984 isn’t is any direct reference to George Orwell, even if record label Joyful Noise Recordings has temporarily republished the novel with “Tim Kinsella” and “Chicago” substituted for “Winston Smith” and “London,” like so: “The flat was seven flights up, and Tim Kinsella, who was thirty-nine and had a varicose ulcer above his right ankle, went slowly, resting several times on the way.” 1984 the album has none of its namesake’s fascist terror and surveillance paranoia; it’s not a social parable but a starkly individual document. Ausikaitis writes with a self-consciously autobiographical naiveté and an attention to poetic detail too specific for fiction. “Tiny Baby” and “Vertigo” recall the events of her childhood in the random-seeming pattern of memory that’s organized by places and aberrations rather than linear time; one’s life story is not cataloged back-to-front like a history book, but by some other, more arcane organic index.

At live shows Ausikaitis performs with a musical art object she’s dubbed the “Fake Guitar,” but her primary instrument is her voice, trained as an adult to genuinely unusual effect: sometimes a nasal twang, a pleasantly bowed croon, or (on “Vermont Girl”) a self-serious Beat Happening bleat. Seamlessly manipulated, ululating vocal spirals blend “Vertigo” into the standout “Punk Kid,” as a groovy, billowing undertow propels one of Ausikaitis’s most memorable and gently satirical lines: “All my life, I’ve been eating shit / Look at me, I’m a real punk kid.” The only sense of violence comes in the frantically thundering acceleration of “People Pleaser,” as Ausikaitis shrieks and growls, “Just die!”; when the moment passes, the band lull into gently strummed acoustic guitar and blown-out kazoo effect on “Psy-fi / Fantasy,” as if stepping down from a bad trip into pleasantly psychedelic Flaming Lips-dom.

As much ground as 1984 shares with Joan of Arc’s previous work by virtue of its wry humor (“Forever Jung”) and commitment to the anti-formulaic, it stands alone—if only because a sincere, sensitive attempt to get at the particular and peculiarly alien quality of childhood is such an uncommon thing. Ausikaitis’s work is an empathetic gesture, allowing listeners to substitute her words of self-discovery on behalf of their own half-buried formative memories. There’s a mental practice in her stream-of-consciousness narration and its meditative accompaniment, as she sings on “Truck,” about drifting into oneself during a long road trip: “There’s no need to close the door / On your personal hole / I’ll tell you why / It’s a place where only you can go.” An odd gem in a catalog full of them, 1984 is a rewarding left turn from a band who’ve remained interesting for so long because they’re less likely to fall off than wander.