Anthony Bourdain was often wrong. The 61-year-old celebrity chef and television personality died Friday, June 8 of an apparent suicide. His death was horrifically tragic news to wake up to, particularly as someone who is the son of immigrant parents. In fact, while reading social media, it seemed like many immigrants and immigrant-raised people who knew and watched Bourdain felt a specific pain when learning of the news.

Bourdain may have been wrong about a lot of things–he would revisit cities if he felt he didn’t do them enough justice–but he always wanted to know the right version. He traveled the world trying different delicacies and street food while learning about the landmarks, cultures, and people he met. A famous quote of his was widely shared after his passing that grasped his spirit succinctly: “If I’m an advocate for anything, it’s to move. As far as you can, as much as you can. Across the ocean, or simply across the river. Walk in someone else’s shoes or at least eat their food. It’s a plus for everybody.” It wasn’t always so easy to find a celebrity chef who seemed to care about the people responsible for making their food, but Bourdain was well-known to be incredibly kind to those all over the world who created his favorite dishes. His sense of warmth, wonder, and genuine empathy guided his food writing and television programs, CNN’s Parts Unknown and the Travel Channel’s No Reservations.

It was there in his examination of the ultimate southern staple, Waffle House, and it was there when he talked about taking former president Barack Obama to Vietnam. But, for me, the best example of how he cared about the countries and cultures responsible for his favorite foods was when he sought out the diverse and global community of immigrants in the city of Houston during an episode of Parts Unknown. Bourdain came in with a simple premise: We (himself included) have dumb misconceptions about what life in a Texas city is like, sometimes forgetting that the melting pot there isn’t exclusive to the United States-Mexican border. Where plenty of foodies sought out hip, trendy barbecue or Tex-Mex restaurants, Bourdain wasn’t interested in something that basic.

“Close-minded, prejudicial, quick to make assumptions about places different than where they grew up. I’m not talking about Texas, I’m talking about, well, me,” Bourdain says at the start of the episode, before explaining that Houston is a city that reflects the immigrants, refugees, black Americans, and other local communities of color that call it hoome. The episode is dedicated to the marginalized, allowing them to share their culture and the food they love with pride. Bourdain explains things to give context and asks questions that let the people he meets take control of the narrative, but he is not overbearing, gross, or mugging for the camera. He instead acts as a journalist, submerging himself in the story but never presuming it’s his own.

The episode begins at Keemat Grocers, a supermarket in Houston’s Little India neighborhood, where an extravagant Bollywood dance party takes place while the mostly Indian residents shop and watch. The party is engineered and hosted by Sunil Thakkar, the owner of local Masala Radio. He’s later interviewed by Bourdain in Himalaya, an Indian-Pakistani restaurant, and gives perspective on the idea of “America” and the strong sense of international community in Houston. “On my street: 18 homes and 12 of them are from different countries—India, Pakistan, Malaysia, Indonesia. And once you live together you become family,” Thakkar tells Bourdain.

Bourdain then goes to a Quinceañera for Evelyn Araña in the Pasadena neighborhood of Houston. Here we see how Houston’s large Mexican population has created an entire Quinceañera industry, where families and friends alike compete to throw the best event for their 15-year-old daughters. It’s a gorgeous showcase, Araña’s quincé is elegant, extravagant, and full of familial joy. It’s a quick scene and one that features no mention of food but that wasn’t the point. Bourdain was making a statement about how foodie voyeurism can often overlook the culture of the communities that produce the food itself. Food, as with music, was communal and political and couldn’t exist as it does otherwise.

This is further exemplified when he visits Lee Senior High, the most ethnically diverse school in Houston, with a Vietnamese principal and a student body that’s 80 percent immigrants for whom English is a second language. Houston’s low cost of living but chance for economic growth is attractive to people who come to this country for opportunity, and it shows in the suburb that houses Lee Senior High. In the episode, a teacher notes people from countries as diverse as “Salvador, Vietnam, Iraq, [and] Syria” come from nothing and make the impossible happen. While that might be an oversimplification, it’s clear that the kids and their families aspired toward the American Dream, carving out a piece for themselves and in tribute to the countries they previously called home in the process.

#SLAB #Houston pic.twitter.com/wfM2r5e53e

— Anthony Bourdain (@Bourdain) June 11, 2016

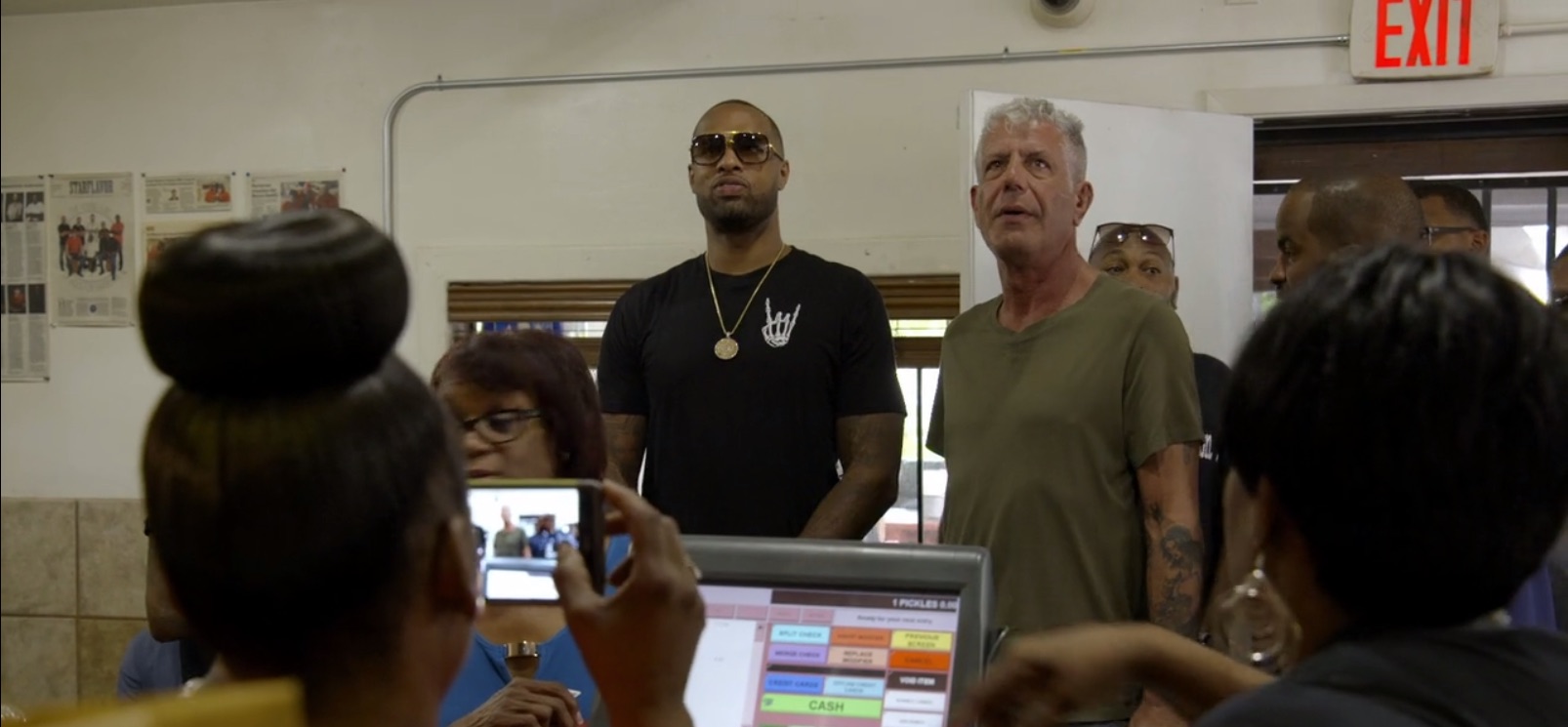

But Bourdain was clear to show that it’s not just immigrants that make Houston. It’s commonly accepted that the black American population there has created some of the best barbecue in the country and influenced the current rap landscape as much as anywhere else, a fact Bourdain highlights when he meets with Slim Thug. The rapper takes Bourdain to MacGregor Park to show off the city’s car culture, involving tricking out cars or “slabs” with candy-paint, luxury upholstery, and heavy trunk-rattling bass upgrades. Slim Thug, his friends, and Bourdain eat some of the best barbecue in the city, and talk about the Houston rap scene and lean, the codeine-based syrup made famous in Houston.

The scene demonstrates something many people loved about Bourdain: how comfortable he was in any surrounding, accepting of the fact that he was clearly out of place. The Houston episode in particular felt emblematic of his understanding of the way food, music, and humanity were inextricably interwoven–and his visits to the Indian, Mexican, Vietnamese, and Black food-halls came hand-in-hand with their musical traditions and loving attention to detail. He went to a state proudly designated as red-blooded American and pointedly focused on the immigrants that made it so.

Bourdain’s desire to learn was infectious and genuine, making him an ideal audience surrogate and host. His guests were comfortable around him because of that sincerity, something Bourdain was clearly grateful for. That he loved the uniqueness of food and considered it with thoughtfulness and excitement was a given. The beauty of Anthony Bourdain was that he took that same care and detail, and applied it to the people he met along the way.