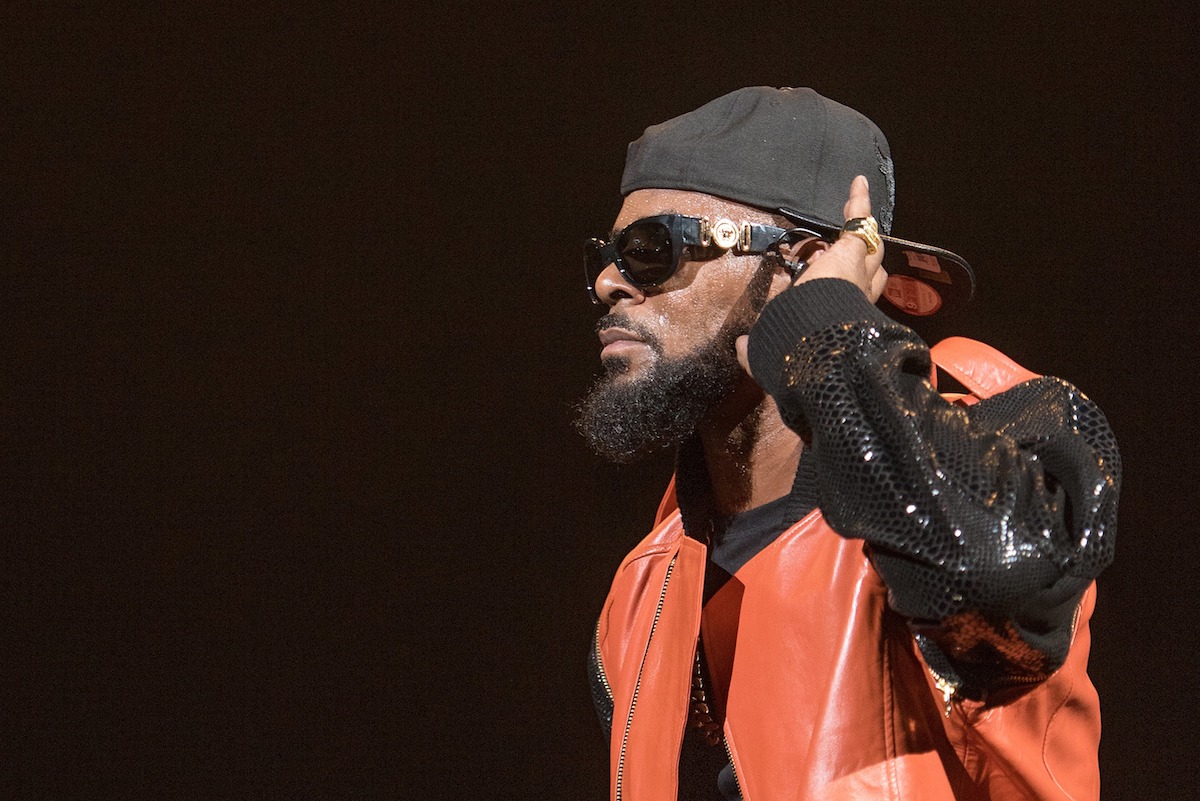

Yesterday, Spotify announced that it was pulling R. Kelly‘s music from its numerous editorial and algorithmic playlists. Due to a new update to its public hate content and hateful conduct policy, the streaming platform says that it will cease active promotion of the singer’s music on its official popular playlists, while still making it available within their catalog through their search feature, related artists tool, and other navigation options. Spotify also quietly removed music from rappers XXXTentaticion and Tay-K from its playlists; the former allegedly beat and strangled his then-pregnant girlfriend in 2016, while the latter is currently in prison on capital murder charges.

On the surface, it seems that, at least with Kelly, the move has a lot to do with mounting public pressure for action against the vocalist. Kelly has been accused of numerous incidents of sexual misconduct just in the last few months; recently the celebrity-backed Time’s Up campaign called on Spotify and others to remove the artist’s work from their catalogues. As more and more new victims continue to come forward, employees and musicians have distanced themselves from the vocalist, even as Kelly has consistently denied all accusations in official statements and through TMZ-sanctioned exclusives.

Unlike platforms like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and others, Spotify seems uniquely intent on getting its hate speech policy right. Written in consultation with the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Anti-Defamation League, GLAAD, and more groups, the company provides a careful definition of hate content, described as “content that expressly and principally promises, advocates, or incites hatred or violence against a group or individual based on characteristics” such as race, religion, sexuality, ethnicity, gender identity, and veteran status, among other minority statuses. Similarly, the company has also now defined “hateful conduct by an artist,” which states that though, in theory, they don’t censor music because of an artist’s “creative behavior,” they do want editorial decisions to “reflect their values.” “When an artist or creator does something that is especially harmful or hateful (for example, violence against children and sexual violence), it may affect the ways we work with or support that artist or creator),” the definition continues.

This isn’t the first time Spotify has publicly dealt with hate speech. Last year, the company pulled a number of bands with white suprematist ties from the platform completely after Digital Music News published a story titled “I Just Found 27 White Supremacist Hate Bands On Spotify.” Again working with the Southern Poverty Law Center, the company then said that while it believes record labels are “first hand responsible” for their output, “illegal content or material that favors hatred or incites violence against race, religion, sexuality or the like is not tolerated by us.” The move came in response to widespread action against white supremacist organizations across the web, with other platforms like Facebook, Reddit, Twitter, PayPal and more taking a stand against the “Unite the Right” demonstration in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Also Read

WHY SO MANY MUSIC TECH DEALS FAIL

At the same time, an artist’s departure from featured playlists isn’t a complete removal from the platform, and the decision seems more an attempt at compromise than steadfast, comprehensive decision. While a large portion of Spotify’s own identity has been built around the production of finely-tuned playlists on the platform, a still-significant number of users seek out content through Spotify’s search and other navigation techniques. Despite the rise of hyper-popular, industry-transforming playlists like RapCaviar, Undercurrents, and Discover Weekly, exclusion from Spotify’s own official playlists is very different than exclusion from the service completely. Other popular third-party playlists from major labels like Filtr (owned by Sony), Digster (owned by Warner), and Topsify (owned by Universal) have not announced any plans to remove these artists, or others accused of hate speech, from their playlists.

In positioning itself as a new kind of authority and policeman on the platform, Spotify ventures down a slippery slope in the expected oversight of its entire catalog. Were it to adequately assess music from every artist ever accused of domestic violence, sexual assault, or even “hate speech”/“hateful conduct” as they’ve defined it, music from Gene Simmons, Stephen Tyler, David Bowie, Chris Brown, Tupac, The Beatles and many, many others would certainly be caught in the crosshairs—an argument made explicitly by XXXTentacion’s manager. Following this logic, are accusations alone enough, or does the musician have to be officially convicted of the crime in question? (R. Kelly, for instance, has never been found guilty in court. In its attempt to draw boundaries for a specific code of conduct as tied to R. Kelly, Spotify alludes to a future where the near-endless history of its global music archive is a site for constant scrutiny, even in instances where the court of public opinion is either largely decided, or potentially irrelevant to continued access to the artist’s musical contributions.

At the same time, as Spotify has gone public and been forced to grow into its role as the world’s largest streaming platform, the move to control hate speech feels emblematic of a broader vision for the company amid numerous changes. In addition to announcing a new mobile free tier, Spotify recently said that they’re aiming to become a “R&D department for the entire music industry,” taking a page from the Netflix playbook in an attempt to bring new market efficiencies to the music industry at large. Other efforts like their “self-driving music” initiative look to improve on the extensive “machine listening” analytics already guiding many company decisions.

With this ambitious scale in mind (not to mention looming venture capital debt still potentially hanging overhead), it’s hard to think that the company would let a simple #Time’sUp PR scandal hold them back. Yet as for-profit platforms come to mediate more and more everyday cultural access, questions about representation and censorship loom heavy over an entire industry now reliant on such platforms for regular income. For companies like Facebook and YouTube, users have long been left in the dark about the limits of their freedom of speech on the platform, with YouTube video creators frequently frustrated by the demonetization of their videos without a clear explanation why. Arbitrarily enforced by platforms mostly in response to PR scandals (like YouTube’s recent child exploitation crisis), current content moderation policies tend favor viral outrage over smaller-scale flagging, frequently offloading as much responsibility to content creators as possible in the process.

While a baseline attempt to provide a definition of illicit behavior for creators is a welcome development from other approaches, the fact that what’s at this point essentially a streaming monopoly can arbitrarily enforce such rules unchecked is a hard pill to swallow. And without a foreseeable process for evaluating such ambiguities, the gesture sets a unique precedent for artists, labels, and an entire industry now reliant on the platform to survive, with expectations for even the simple inclusion of a song in one of the world’s largest online music archives now in theory open to more and more potential scrutiny. What does it mean to at any moment be potentially stripped of a money-making platform without due process, or even a process of appeals? If Spotify decides what histories get included in the public archive at all, then at least users deserve to understand the terms.