“Perhaps I’m unique because people are so dull. I’m not very good at being dull.” —Morrissey

“I have nothing to declare but my genius.” —Oscar Wilde

We’re at London’s Cadogan Hotel, sitting in the very room where Oscar Wilde, patron saint of every British eccentric, pansexual, and dreamer, from Quentin Crisp to Steven Morrissey, was arrested back in April of 1895. Surveying the chamber as he polishes off another cup of tea, Morrissey declares himself “almost speechless. It’s a very historic place, and it means a good deal to me to be sitting here staring at Oscar’s television and the very video he watched The Leather Boys on.”

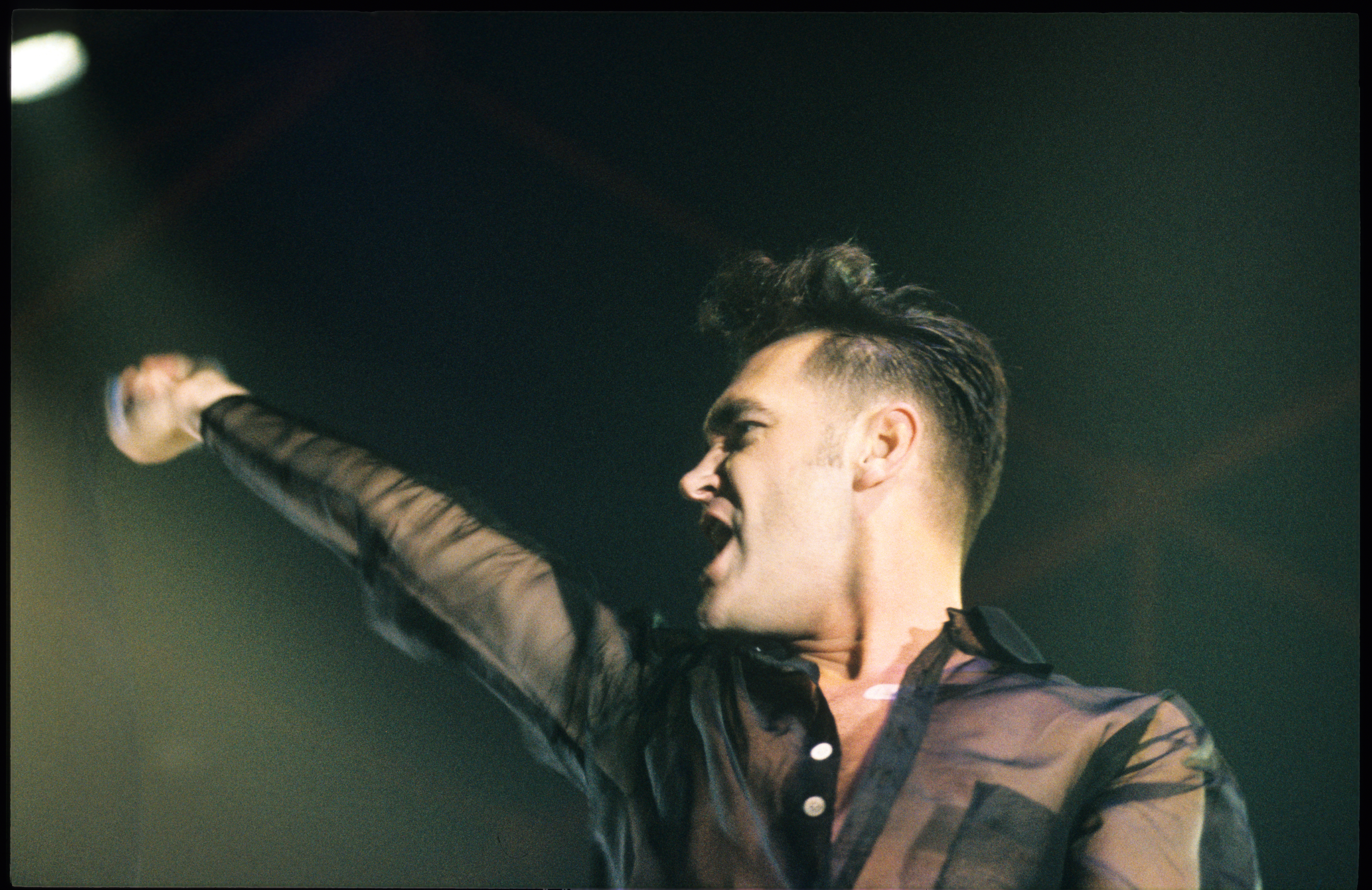

Morrissey smirks, sits back on the couch and helps himself to another cheese sandwich. The former Smiths vocalist, lyricist extraordinaire, celibate aesthete, and charismatic bigmouth seems to like cheese sandwiches. (A militant vegetarian, he titled an early Smiths album Meat Is Murder.) Sporting an Oscar Wilde T-shirt and a quiff like a cliff, Morrissey is preparing to follow in Wilde’s footsteps, leading the charge against all that is stupid, ugly, or boring.

“A few bricks need to be thrown through a few specific windows, whether we’re discussing Tiffany or nuclear waste.” He looks around the room again. “I gladly would if I thought there were any troops, but a one-man army can get a little strenuous. Who would make the tea?”

Years ago, when the Smiths were rising from the ashes of post-punk England, Morrissey and his followers were united by hatred, “hating everything, but not being offensively hateful. It was hate from quite gentle people.”

Morrissey became the hero of the lonely, the disenfranchised, the outsider, speaking, some might even say singing, for the loners who hated being alone but couldn’t stand the company of others. Viva Hate, his first solo effort, continues his railings against brutality, ignorance, British Prime Minister and Dog Lady Margaret Thatcher, and the world of pop music, a world he claims has been “infiltrated by idiots,” dismissing rap music and hip hop as “pop thuggery, a great musical stench, very offensive, artless and styleless, remarkably illiterate.”

“If we talk about Tiffany and Belinda Carlisle and the whole influx of Debbie Gibsons, we can quite easily be accused of giving too much attention to obviously untalented, obviously discountable people. But these people are ruling the world of popular music, and I think it’s a serious epidemic.

“I don’t believe that people are going out and buying certain records in the Top Ten. It’s impossible! Even taking into account the possibility that thirty percent of the public might be seriously mentally unspectacular.”

It’s less than a year since the Smiths imploded. Strangeways Here We Come, their last album, was released in the fall of 1987, though the band had dissolved earlier that summer. Morrissey last saw his songwriting partner and guitarist, Johnny Marr, in May of ’87, and lost contact with drummer Mike Joyce and bass player Andy Rourke last July.

Since Marr quit, he’s played on Bryan Ferry’s Bête Noire, written with the Pretenders, recorded with Roy Orbison, and earned plaudits for his work on Talking Heads’ Naked. Rourke and Joyce, meanwhile, have been touring with Irish songstress Sinéad O’Connor and recording with Adult Net (a spin-off of the Fall.)

For Morrissey, who once claimed that “the group are like a life support machine to me,” the separation meant a period of “extreme emotional turmoil” during which he was “literally bedridden.”

More tea, dear?

Thank you.

“The Smiths were like a painting,” he muses sadly. “Every month you’d add a little bit here and a little bit there. But it wasn’t quite complete, and it was whipped away. I find it hard to adapt to that. Even people who enjoyed the music thought the split was very timely. It’s very popular attitude that the split occurred at the right time. I get quite violent when people say that to me.”

The Smiths self-destructed at the peak of their commercial success. Even as the cheerfully titled “Girlfriend in a Coma” entered the British charts at Number 13 (an unprecedented achievement for a record on an independent label), the band was getting ready to, ah, pull the plug. Andy Rourke’s battle with heroin was an ongoing trauma, and the addition (and eventual sacking) of second guitarist Craig Gannon led to accusations that the Smiths were metamorphosing into the Rolling Stones, a bunch of hacks and poseurs living off the fat of the pop landscape. “Will the journalists please stop throwing things,” Morrissey cried at one of the band’s last live appearances.

“It was such a tight little unit,” Morrissey sniffs, “and it seemed that nobody could penetrate the Smiths’ secret, private world. On the occasion that somebody did break through, everything fell in twenty-five different directions.”

Clearly Johnny Marr needed other outlets for his guitarwork. Although occasional solos crept into songs like “Shoplifters of the World Unite” and “Sheila Take a Bow,” the crafted instrumentals that graced several Smiths’ B-sides disappeared. Rumor has it that Morrissey opposed their inclusion or refused to write lyrics for them, although Morrissey claims that “there was never any political maneuvering. It was never a battle of power between Johnny and myself. The very assumption that a Smiths instrumental track left Morrissey upstairs stamping his feet and kicking the furniture was untrue.”

Still, Morrissey refused to write lyrics for “Money Changes Everything,” which, after the Smiths’ demise, passed into Bryan Ferry’s hands and became “The Right Stuff” (the first single on Bête Noire).

Whatever the reasons, after six years the Smiths ceased to be, six years after they’d gate-crashed the charts and epitomized their time and their place.

“I think the Smiths totally spoke for now,” says Morrissey, consuming even more tea. “[We were] definitely the most realistic musical and lyrical voice of the Eighties, and it’s not just self-bleating.”

WHAT NOW, LITTLE MAN?

Morrissey has stylishly confounded those critics who believed that his songwriting partnership with Marr was a one-off, like Lennon/McCartney or Jagger/Richards. Viva Hate, a typical blend of Mr. M’s aggression and introspection (from the opening guitar scream to the final slash of the guillotine) was cowritten with longtime Smiths’ producer/engineer Stephen Street (involved with the band since 1984’s “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now.”)

“It was the last thing on earth I expected,” recalls Morrissey. “He simply sent a tape of his songs and said, ‘Would you like to record these?’ He was very shy about it.”

Marr’s uplifting riffs and clever compositions have been supplanted by the moody guitars and keyboards of Durutti Column’s Vini Reilly. Musically, the record’s less immediate than much of the Smiths’ work, more a vehicle for Morrissey’s poetry and distinctive, fairly tuneless vocals. Lyrically, his preoccupation with Britain in the early Seventies and with his own childhood and adolescence continues. “Late Night, Maudlin Street” deals with moving away, leaving friends; “Dial-A-Cliche” reflects on the difficult relationship between father and son (“Grow up/Be a man/And close your mealy mouth”); and “Suedehead” takes its title from a British trash novel which dealt with street gangs.

“A suedehead was an outgrown skinhead,” Morrissey explains, “but outgrown only in the hair sense. An outgrown skinhead who was slightly softer. Not a football hooligan. Back in ’71, when youth cults were on the rampage in Manchester, there was a tremendous air of intensity and potential unpleasantness. Something interesting grabbed me about the whole thing. I don’t think there were any good guys; everybody had several chips on several shoulders. There was a great velocity of hate. Everybody got their head kicked in. It’s made me what I am today.”

It was a grim time to grow up, particularly in the depressed and rain-soaked North. The hippie dream was over, and the Sixties had just stopped swinging. “It was the beginning of severe unemployment,” Morrissey recalls, “and people really believed that if you didn’t work you were slovenly and lazy and all those other interesting things. They still do, but it’s less aggressive now because we realize that there’s a world crisis, whereas then it was a terrible physical disease to stay at home and paint your face.”

Amidst the sadness and decay, he found solace in the music of T. Rex, Roxy Music, Lou Reed, and, of course, David Bowie, from whom Morrissey drew both solace and the idea that it was possible to invent (and re-invent) your own persona. It got him through the bad times.

“The last two years I didn’t actually go to school, it was that bad. I just walked around shops. I found the teachers and the tattiness of the entire school very annoying. There were always strikes, blackouts, winters of discontent. I thought, ‘Why bother?'”

Does he regret his lack of academic qualification?

“No, because I’ve not done that badly. I’ve got a very nice coat, and I’m sitting here at the Cadogan Hotel. What more do you want?”

“A few bricks need to be thrown through a few specific windows, whether we’re discussing Tiffany or nuclear waste.”

CEMETARY GATES

Having, as he claims, a healthy interest in dying and a fascination with doomed and suffering artists, it’s no surprise that the “Suedehead” video features Morrissey “messing with James Dean’s soil” out in Indiana. Obsessed with Dean since childhood, Morrissey published a cut-and-paste biography of the late actor, titled James Dean Is Not Dead, back before forming the Smiths.

He identifies with “that kind of mystical knowledge that there is something incredibly black around the corner. People who feel that way are quite special and always end up in a mangled mess.”

“I have a dramatic, unswayable, unavoidable obsession with death. If there was a magical, beautiful pill that would retire you from this world, I think I would take it.”

“Call me morbid, call me pale,” he advises on “Half a Person.” “I wear black on the outside, because black is how I feel on the inside,” he whines on “Unloveable.” But to project Morrissey as totally morose is to ignore the seam of black comedy that runs through his creations. From the opening salvo in ’82 (“Hand in glove/The sun shines out of our behinds”) to Viva Hate’s “Hairdresser on Fire” (“You are repressed but you’re remarkably dressed”), Steven Patrick Morrissey has been laughing at English life even as he’s been railing against its injustices.

His lyrics have clearly struck a chord with a generation of English youth, educated to expect more from life than Britain can now offer them. Still, he remains more a provocateur than an activist, sending cheeky messages from the sidelines.

HOW BIG’S THE CLOSET? CAN WE COME IN?

“I have always expected some fictitious spread like MORRISSEY INJECTS SLEEPING NUN WITH COCAINE, but there’s really nothing to report, and I’m half humiliated to have to admit that.”

Still, he revels in his ambiguous sexuality, and he’s received acres of press by coyly attesting to his constant and, by now, seemingly quite coveted virginity. And in the age of AIDS and sexual fear and hysteria, what could be more fashionable? Or more romantic?

Isn’t there the danger that success will spoil him, tempt him away from that? Doesn’t he have to keep a strict hold on himself to maintain a meatless, drugless, and sexless existence?

“Yes, it’s stricter now than it ever was,” he asserts. “I think as long as I make records, I’ll be sealed up in this vat of introspection. Maximum attention has got to be given to everything I do. And, in order to concentrate absolutely perfectly on everything, I have to give up sausages.”

BIGMOUTH STRIKES AGAIN

“We really have everything in common with America nowadays. Except, of course, language.” —Oscar Wilde

A hundred years ago, when Wilde declared his genius all over the States, he was lampooned by the press for his style, and his espousal of aestheticism and the English Renaissance. Less outrageously fashionable, but still managing to be stylish, Morrissey is equally likely to ruffle a few feathers, more through his persona than through his music, through his arrogance and his continued insistence on his importance.

“Sometimes I find it hard to believe that anything truly violent can happen again. Nobody is brave anymore. Nobody makes any brave records, any brave statements.”

He’s never been optimistic, and frankly, this is not an optimistic age. Pop music, the language of the streets, has become more and more escapist, more and more divorced from the battle cry it once was.

Does he see any possibility of a Smiths reunion, of a re-marshalling of old forces and powers?

“Yes, I do entertain those thoughts. As soon as anybody wants to come back to the fold and make records, I’ll be there. But,” he adds, “I’m nearly 29. [Morrissey turned 29 on May 22, 1988.] I’ll be dead in a couple of years. I don’t want to walk onstage with a hair transplant, with shoes on the wrong foot. I don’t want to haul the carcass across the studio floor and reach for the bathchair as I put down a vocal.”

More tea, dear?

Thank you.