Art exhibits focusing on the oeuvre of celebrities and musicians are not infrequently looked down upon by art aficionados and critics as unconvincing cash grabs. However, it seems fair to say that there are few subjects—certainly as far pop stars go—as worthy of the seriously-minded multimedia exhibition treatment as David Bowie. The elliptical 500-object David Bowie Is, which originated at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 2013, has proven itself to be both popular and substantial during its tour of the world during the last several years. It is now beginning its 11th and final run at the Brooklyn Museum in New York, and as the exhibit’s curators point out, New York City is a fitting place for the show to end.

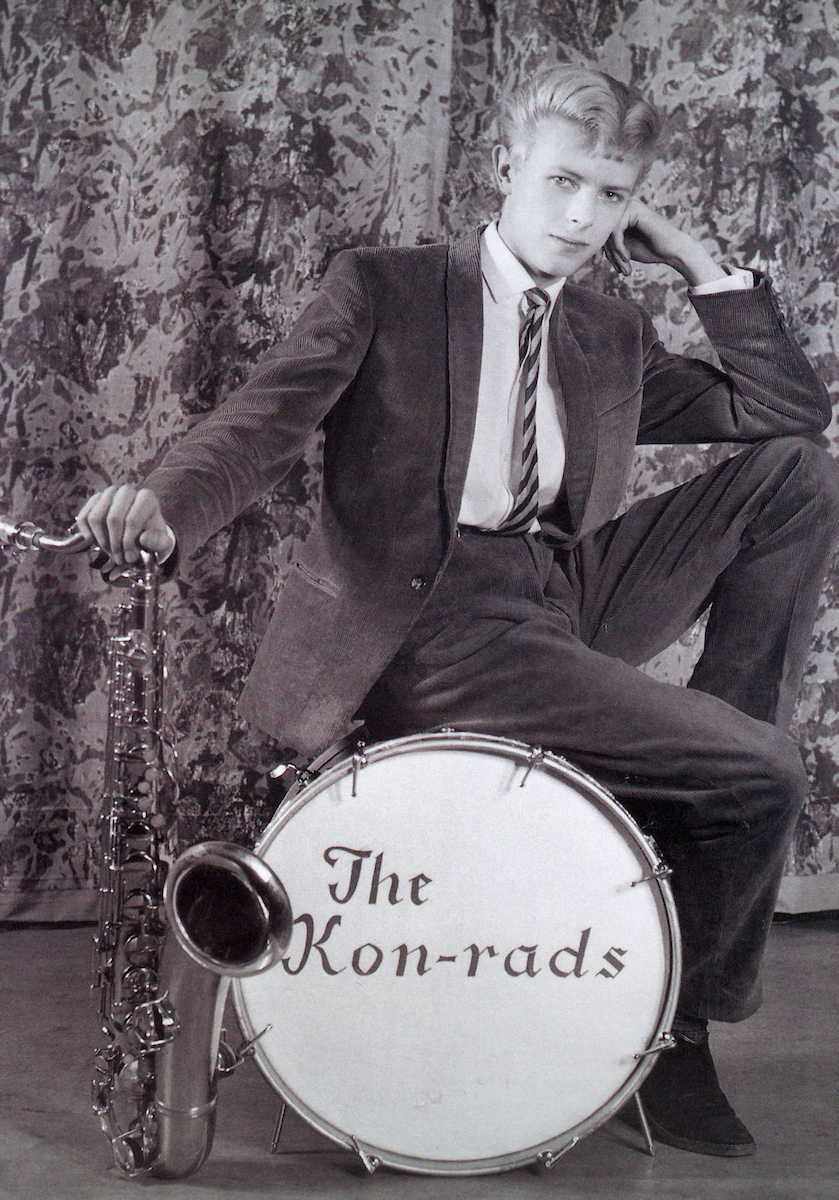

Bowie lived in Manhattan longer than he did anywhere else in his adult life. His final works were largely produced in the city, and he died there. As the first section of the exhibit outlines, the art world of NYC in the mid-60s also exerted a strong pull on the teenage, Brixton-born Davie Jones, who was then only contemplating becoming David Bowie (and therefore not sharing a moniker with a Monkee). Bowie’s early manager brought the young singer-songwriter an early copy of the prototypical New York avant-rock LP The Velvet Underground and Nico. Bowie, fully enamored, began covering songs from the album before it was even released in the UK.

It’s hard to pick selected artifacts from Bowie’s collected works that serve as good summaries or microcosms of his full career. No one of even his greatest albums, or a documentary or biography, can both reasonably articulate the breadth of his achievement and put across his art’s visceral, multidisciplinary power. David Bowie Is comes close to giving a rich and convincing impression of these things together. It is a fully unified visual, physical, and auditory experience which both shows and explains how visual art, fashion, theater, androgyny, sexuality, and changing social trends were reflected in Bowie’s music, as well as being essential to his extroverted public self-presentation. Though the show is bewilderingly laid-out–by design, it seems–the exhibit tells a palpable, sometimes even relatable story about an artist that was as much the consummate student as a peerless innovator. Bowie inevitably saved himself from any possible accusations of imitation by his natural, supreme magnetism and perpetual ability to synthesize his influences into strange new amalgams. In most cases, his creations found greater mainstream audiences than the work that inspired them, and ultimately ceased to resemble their points of inspiration.

The exhibit begins systematically, creating an image of the teenage Davie Jones as an appealingly curious and confused young hipster. It highlights all of the outré art, musical theater, dance, rock’n’roll, and films that he stumbled onto–anything interesting to which he was able to gain access. In one interview woven into the exhibit’s incidental audio track, Bowie recalls listening to avant-garde jazz (Eric Dolphy, specifically) long before he knew he liked it, because he had decided that it was important and cool. He remembers reading books that were way over his head for the sake of doing so; later, there is a curated stack of Bowie’s espoused top 100 books—obviously a deathly cool selection. Anecdotes like the Dolphy one crop up throughout the exhibit, providing charming detail. One of the central throughlines in Bowie’s career, the exhibit reminds us, is made up of breakthrough moments with others’ art which would help inspire his newest character, costume, and process change.

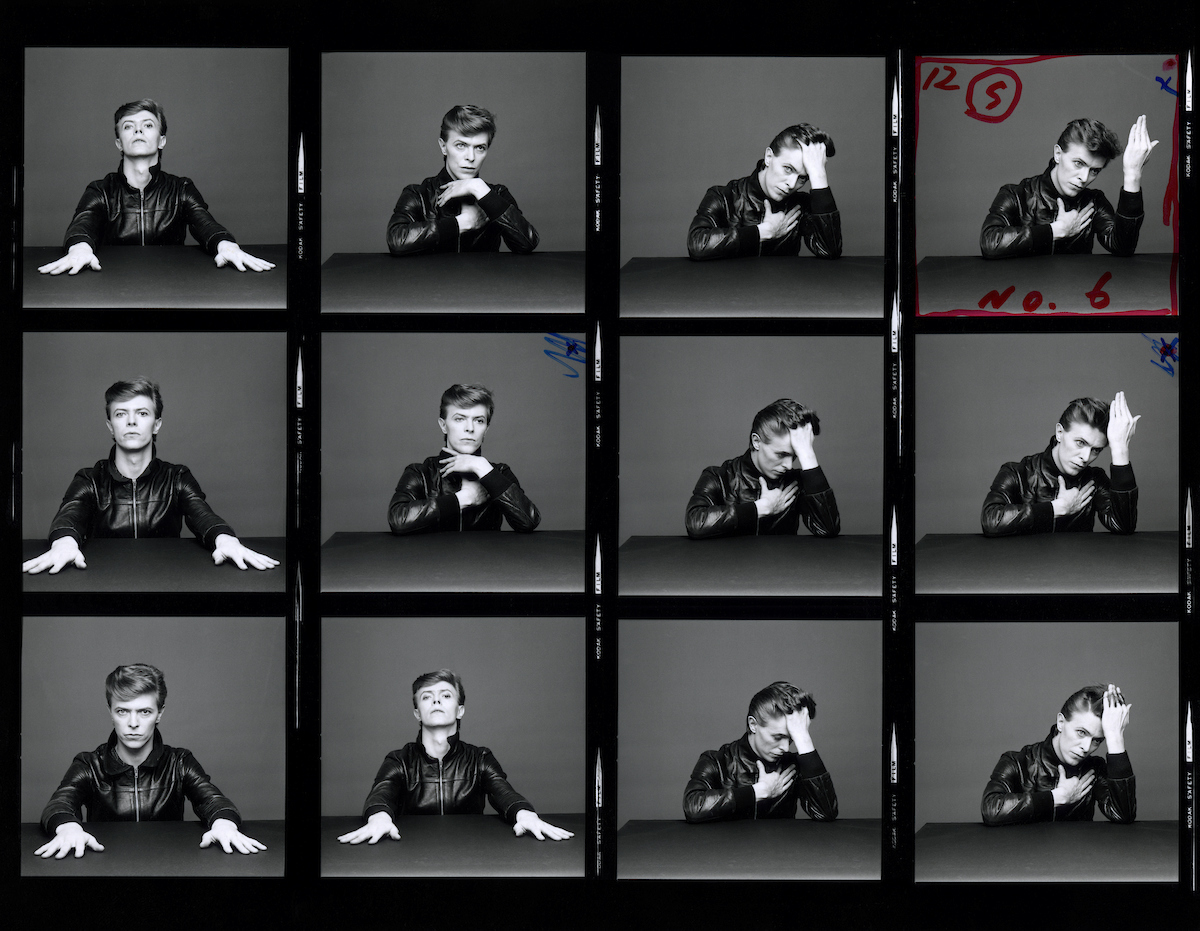

As Bowie’s rate of artistic consumption, socialite activity, and both creative and literal costume changes increases to a dizzying fever pitch as the viewer moves into the mid-1970s, the exhibit complicates and folds into itself more and more. It eschews clear chronology, pitting costumes and concept art from less revered and no less ambitious albums like 1995’s rich, avant-garde song cycle Outside and 1997’s variegated electronica experiment Earthling against more classic models from the Aladdin Sane or “Thin White Duke” era. Imposing mannequins of these various Bowies tower over the proceedings; relatively forgotten figures like a Hamlet-cape-clad character from the mid-’80s are brought out of obscurity and made physically manifest again.

As Bowie’s rate of artistic consumption, socialite activity, and both creative and literal costume changes increases to a dizzying fever pitch as the viewer moves into the mid-1970s, the exhibit complicates and folds into itself more and more. It eschews clear chronology, pitting costumes and concept art from less revered and no less ambitious albums like 1995’s rich, avant-garde song cycle Outside and 1997’s variegated electronica experiment Earthling against more classic models from the Aladdin Sane or “Thin White Duke” era. Imposing mannequins of these various Bowies tower over the proceedings; relatively forgotten figures like a Hamlet-cape-clad character from the mid-’80s are brought out of obscurity and made physically manifest again.

The section focusing most closely on the “Berlin era” is the show’s swirling nexus, highlighting a wonderful mess of conflicting impulses which resulted in some of the most unprecedented, inventive music and live shows in the history of rock. It features several strikingly grotesque portrait paintings by Bowie that give an insight into his inspired, confused, and slightly deranged frame of mind during his years living and often working in the city, during which he also struggled with drug addiction. In this segment, a wide swath of Bowie interests collide: Weimar Berlin (the Die Brucke school of expressionist art, Christopher Isherwood, Brecht, Cabaret), electronic experimentation (a 1974 EMS Synthi AKS recommended by Brian Eno), proto-punk rebellion (his production work with Iggy Pop), nightlife culture, and more. Nowhere in the exhibit is it harder to avoid its central rhetorical question: “What wasn’t Bowie?”

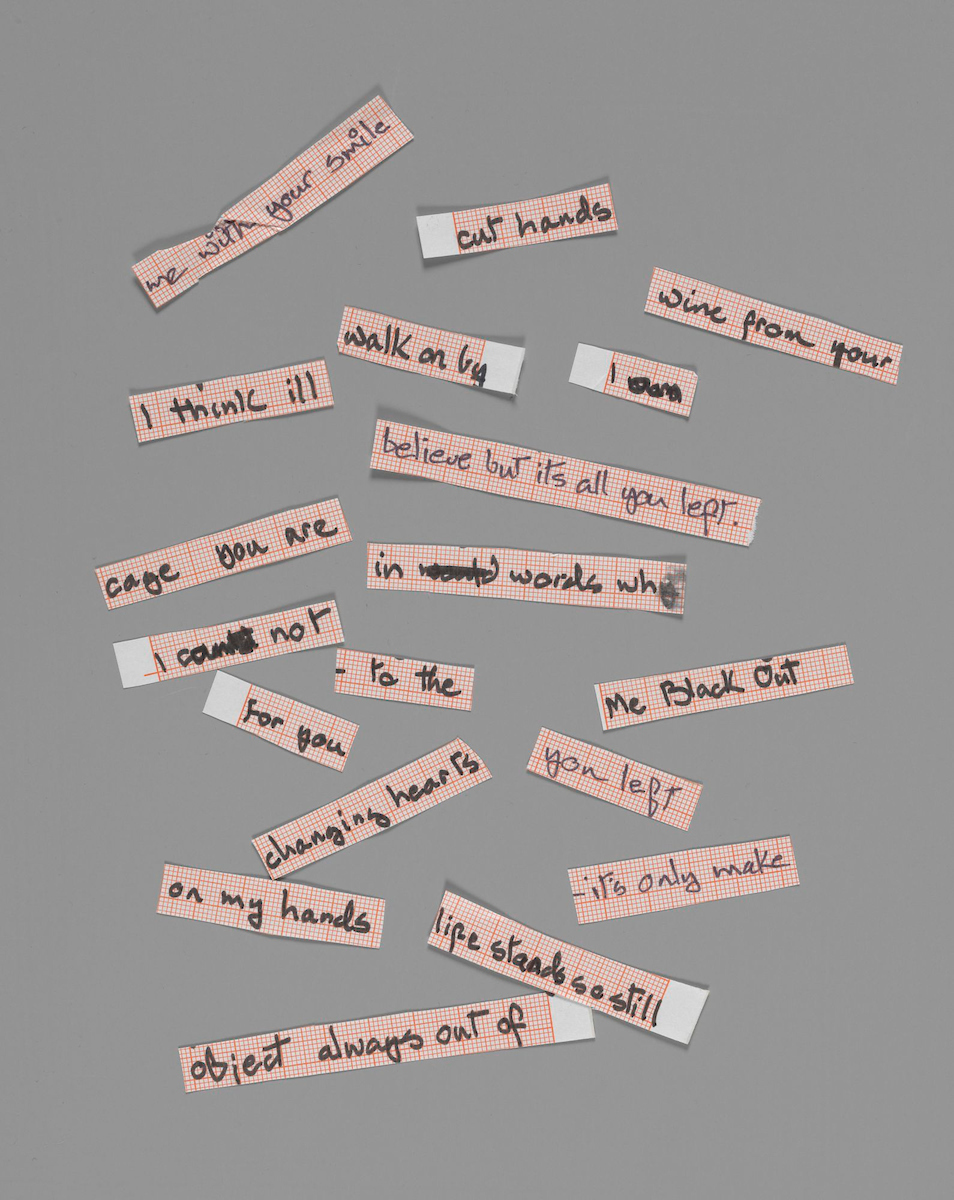

As captivating as it is to simply be in close proximity of otherworldly Kansai Yamamoto and Alexander McQueen stage garb, one of the more fascinating aspects of the exhibit is also its most visually dry: the section dealing with the restless maturation of Bowie’s songwriting. A section featuring notebook sheets and other ephemera emphasizes the commonalities in his lyrics across many different experimental periods. The lion’s share of Bowie songs feature an element of non-linear narrative, free association, or outright chaos, but he always anchors them with pithy lines that throw the whole picture into moving, populistic relief. Just from examining a series of journal sketches, his changing sources of inspiration–and an increasing desire to find new, unusual, and spontaneous inroads to creativity–are evident. We see scrawled, free-associative Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust era librettos inspired by the likes of Orwell, Kubrick, Lou Reed, Dylan, the Beats, and Alaistair Crowley. From there, there are the Oblique-Strategies-influenced “Berlin era” scribblings (including phrases that led to Heroes‘ “Blackout” on little cut-up scraps of paper) and evidence of the more intentional, pop-oriented approach of albums like Young Americans and Scary Monsters. Even later, there’s the results of the custom-made random word generator computer program he used during the making of Outside.

One of the best aspects of David Bowie Is is that, since it predates Bowie’s death, its elements have been altered only lightly to account for the last section of Bowie’s life and his passing. In no way does it feel like a memorial exhibit, with there being only a very limited amount of material from the Blackstar era. Indeed, the in-memoriam-like denouement of the show is somewhat ridiculous. On the way out, there’s the Paul Robertson 22 piece The Periodic Table of Bowie, which attempts to draw together and categorize esoterically every cultural or historical figure of the past (Greta Garbo, Fritz Lang) or the present (Invader, deadmau5) to which Bowie’s sensibilities seem moored. To obsess over his continuing influence, or how his myth has compounded since his death, would be a all-too-messy, massive pursuit. Thankfully, the exhibit doesn’t push it much farther than this piece; his life was mythic enough on its own.

One of the best aspects of David Bowie Is is that, since it predates Bowie’s death, its elements have been altered only lightly to account for the last section of Bowie’s life and his passing. In no way does it feel like a memorial exhibit, with there being only a very limited amount of material from the Blackstar era. Indeed, the in-memoriam-like denouement of the show is somewhat ridiculous. On the way out, there’s the Paul Robertson 22 piece The Periodic Table of Bowie, which attempts to draw together and categorize esoterically every cultural or historical figure of the past (Greta Garbo, Fritz Lang) or the present (Invader, deadmau5) to which Bowie’s sensibilities seem moored. To obsess over his continuing influence, or how his myth has compounded since his death, would be a all-too-messy, massive pursuit. Thankfully, the exhibit doesn’t push it much farther than this piece; his life was mythic enough on its own.

If it shies away from being critical of any of Bowie’s artistic pivots–the fascistic imagery that cropped up in the Thin White Duke period, for instance, or certain moments of overzealous appropriation of black culture–it does aim to explode the canonical image of him. It deifies certain discrete moments of public triumph and influence (the rise of “Space Oddity” following its broadcast on the BBC over footage of the Apollo 11 landing, his controversial, subtly homoerotic, Ziggy-clad 1972 Top of the Pops performance of “Starman,” and more). But its tendency is to scramble Bowieness together into something both mysterious, dizzying, and digestible. Though it is loosely organized around different broad storylines that fans and critics latch onto to tell neat stories about Bowie, David Bowie Is’s most valuable function may be its attention to detail–its clear ability to offer small, alluring surprises, even for obsessives.

David Bowie Is is on display at Brooklyn Museum March 2-July 15. All images provided by Brooklyn Museum.