Although A Seat at the Table currently stands as her opus, Solange hasn’t exactly toured behind it. Instead, she performed this summer at select festival dates, put on a high-concept show at the Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan, and then announced an October “performance series” with dates in California and New York, where she was at Radio City Music Hall this week. This unique performance schedule isn’t due to lack of effort—like the album, Solange’s shows are carefully considered and reference-heavy. For example, the performance series is named “Orion’s Rise,” a constellation that’s been a literary obsession for centuries. Orion’s Belt gets referred to on English poet Alfred Tennyson’s 1847 poem The Princess, where the eponymous figure founds a women’s university after refusing to abide by a world ruled by men.

Men were welcomed to the table at Radio City on Tuesday: Sun Ra Arkestra (who added orchestral accents to her set), the French pianist Chassol, and Earl Sweatshirt—Solange’s Radio City Music Hall openers—are all male-fronted acts. But like the album, the Orion’s Rise shows spring from the need for a restorative space outside of the prevailing patriarchal construct. The performance also celebrates the one-year anniversary of A Seat at the Table, an album that was a respite following a year of death and aggressive anti-black sentiment. As bleak as that year was, this one has been far worse. Before Solange’s hour-long set, a fellow attendee and I talked briefly about our surprise at how it really hadn’t been that long since A Seat at the Table dropped. Nothing distorts time like pain.

Solange acknowledged that A Seat at the Table was born from her own strife, too. “When I handed in the album, I felt so much rage, and anguish, and pain, and trauma that I had to work through,” she said in her lone anniversary-acknowledging monologue. But she was joyful throughout the night—she didn’t mention the world’s ongoing throes outside of her sanguine songs.

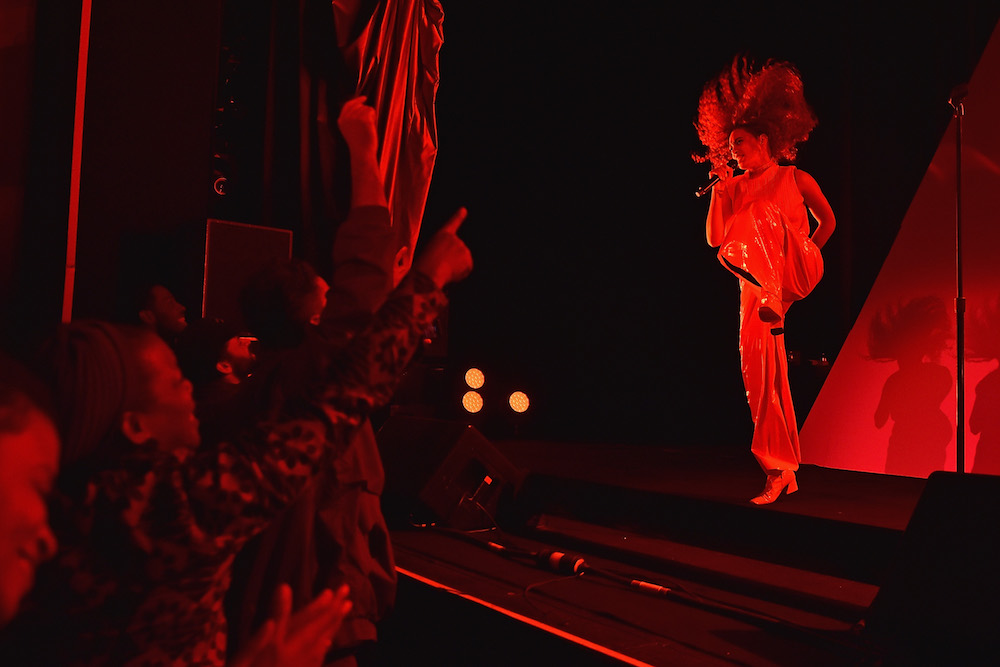

Solange was backed by a large-scale stairway and a band wearing immaculate, sand-white clothes. Two pyramids bordered the stage while a sphere—her star—rested at the center. Like the set design, Solange’s choreography was elaborate but nevertheless human. The climax of “Cranes in the Sky” saw her and her fellow dancers coordinating their squats and arm thrusts in ritualistic precision. This wasn’t a flex, but a performative display of the song’s spiritual surrender. For Seat at the Table’s manifesto “F.U.B.U.,” she excited the crowd as she whined along to a new horn arrangement, one which was partly ethereal, partly “Down for My Niggas.”

While this was undoubtedly Solange’s night—her set even included songs from her 2002 debut Solo Star—the show resonated because the spotlight wasn’t solely fixated on her. She even stood stage-left instead of the center after walking down the stairway upon taking the stage. The musicians swayed and stepped on cue, sometimes raucously so as to express that this wasn’t a staid, regal gathering befitting of the venue. The troupe’s formations were constantly shifting and often asymmetrical on both sides of a stairway, evoking the spontaneity of a black shindig (“I wanna know who’s invited to the cookout” she exclaimed near the show’s opening). Solange also continuously encouraged the audience to dance along, reminding us that the Afrofuturistic utopia didn’t have to end on the stage.

She was fully taking advantage of one the few times she could truly construct that environment; with the exception of Afropunk, the insistent melanin in Solange’s work is inherently less immersive in the predominantly white spaces that are summer festivals. It was omnipresent at Radio City, and the resulting jubilation peaked at the set’s penultimate song “Losing You,” when the crowd’s raised silhouetted hands were kissed by the hovering star’s white light.

It was a show that epitomized A Seat at a Table’s two big ambitions: Solange’s quest to assert herself as a definitive artist and her wish to provide an inclusive space for her people. The latter took precedence in the show’s final song “Don’t Touch My Hair.” In the extended outro, she conducted the horns clarion swells and recessions. Her back was turned to the crowd as she faced her star, which now glowed red.