This one time, at band camp—okay, it was actually Ozzfest 2001, but it really felt like being at camp, and there were bands there, and it was summer—this huge spider bit Linkin Park’s Chester Bennington on the ass. Bennington is one of Linkin Park’s two singers, the one who does the real singing and most of the screaming. The spider was, like, a black widow or something. The welt—which Bennington shows off, with a mix of pride and terror, on Linkin Park’s best-selling DVD Frat Party at the Pankake Festival—is awe-inspiring in a Jackass kind of way: black and blue and about the size of an orange.

Things got very gross very quickly. The glands in Bennington’s neck and armpits swelled up; then, as the poison permeated his bloodstream, he found hard painful lumps all over his boy. “I thought I had cancer.” he says now. He was delusional; he couldn’t put a sentence together. He’d be walking, and a wall would come out of nowhere and smack him. Bennington’s doctor prescribed Cipro, an antibiotic now known for treating inhalation anthrax, but the singer was so confused that he kept addressing his physician as “Dr. Cipro.” Dr. Cipro ordered him to sit out the band’s last two Ozzfest dates, but Bennington refused.

Even under the best circumstances, Linkin Park’s live performances are emotionally and physically brutal, and Bennington would not dial it down—”I don’t like to hold back,” he says, “because that’s how you hurt yourself.” So, for two shows, poisoned and confused, he let out that lung-shredding rebel yell—the sound of a man ripping Band-Aids off his very soul—the way he always does, and jumped off the risers and the amps and the DJ booth, the way he always does. But he had Cipro battling spider venom in his blood, and something about that cocktail made his depth perception go all goofy. “He fell on his face a couple times,” Bennington’s co-frontman, Mike Shinoda, says, “like he didn’t expect the ground to be there so soon.”

If you ask Linkin Park about why they do what they do, about their apparently bottomless commitment to the work of being a band, they’ll say the things big rock bands always say—that they’re in it for the music and for the fans. They’re a big rock band—it’s their job to say these things. But there’s talk, and there’s action, and if, in the course of this story, Linkin Park seem like they’re just talking, think about Bennington performing with poison in his blood, because even if a lot of the people in the heat and dust of the crowd were just there to pound Bud Light all day and heckle Ozzy’s wrinkly warlock ass all night, there might have been someone out there who shelled out 37 bucks because they really needed to scream along.

Also Read

The 40 Greatest Music Video Artists

***

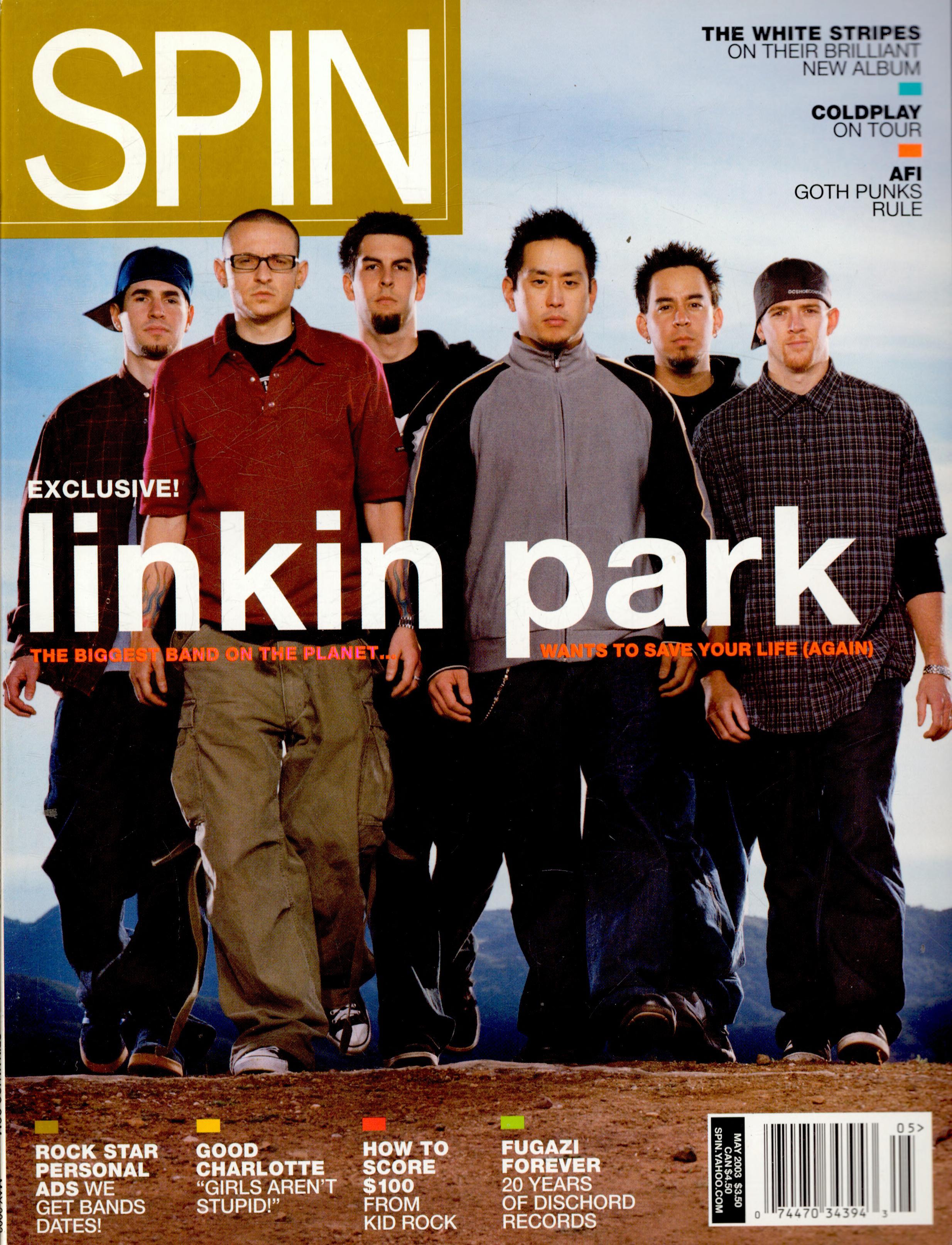

Rapper/producer Mike Shinoda is living proof of just how far an art-school education can take you. When Shinoda, 26, was attending Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design, he was also playing music all night with friends Brad Delson (now Linkin Park’s guitarist, then a UCLA communications major) and Joseph Hahn, who met Shinoda at ARt Center and is now Linkin Park’s DJ. Bennington joined later, after leveling all corners at a 1999 audition. The band’s 2000 debut,, Hybrid Theory—which included a liner note shoutout from Shinoda to his former neighbors “for putting up with us recording this screaming in my bedroom”—became the best-selling record of 2001, thanks to a series of tunefully tortured singles (“One Step Closer,” “Crawling,” “In the End”) and tireless touring, from Ozzfest to Family Values to the band’s own Projekt Revolution.

“They’re really serious guys who keep control of their shit” says fellow Ozzfester Jacoby Shaddix of Papa Roach. “I made good friends with Chester on tour. He’s a punk kid like me, from a fucked-up small town. I’d have to sneak him away to go party—the other guys in the band would be like, ‘Keep it straight,’ but I’d pull him away.”

In 2001, Shinoda and Hahn appeared on the X-ecutioners’ single “It’s Goin’ Down,” helping the New York City turntablist crew score a surprise pop hit. Last year, Linkin Park released Reanimation, an ambitiously weird remix album on which Shindo, Hahn, and hip-hop producers such as Kutmasta Kurt took a digital razer to Hybrid Theory. Underground MCs like Aceyalone and Phoenix Orion showed up to spit, and rock vocalists like Staind’s Aaron Lewis and Korn’s Jonathan Davis showed up to vent. The band gave all the tracks new names—”Pushing Me Away” because “P5HNG ME A*WY”—which made sense, because the record itself sounded like a generation making up a new rap-rock language by scrambling its own codes.

“They’re true fans of the art,” the X-ecutioners’ Rob Swift enthuses. “They’re not like, ‘Let’s have Mr. Hahn here as a DJ for the looks of it. ‘ It’s a real thing with them. I study Hybrid Theory whenever I want to get some inspiration for things I want to do.”

In a genre known for gratuitous nastiness, Linkin Park are an exception—they’re the band you’d trust to escort your sister to a movie, except they probably stand her up to log some extra studio time. Bennington takes pride in Linkin Park’s workaholic rep. “This is a business of love and labor,” he says. “You’re constantly trying to prove yourself, even after you’ve made it. And you have to love it—you have to love what you do, or else you’re going to hate it.”

Love of labor brought Linkin Park here, to Studio City, the farthest you can get from anything resembling Hollywood while remaining in Hollywood. The neighborhood is full of businesses that mind their own business: a smog-check place, a shuttered El Salvadoran restaurant, a 7-Eleven. A head shop across the street advertises Glass Pipes, Huge Selection in sun-faded psychedelic cursive, but otherwise, the area is largely free of distractions, which is how Linkin Park prefer it. They’re rehearsing for an upcoming tour—they’re working. The snack table is heavy with energy bars, the fridge is stocked with protein shakes. Each member has a manila folder “mailbox” on the production-office door where printouts of email memos from the band’s management either accumulate or don’t, depending on how diligent the Linkin Parkers are about retrieving them. Bassist Phoenix’s envelope is empty, Bennington’s is full.

Journalists who visit Linkin Park’s record label to hear Meteora are subjected to everything short of a cavity search: in that same cautious spirit, today, the band will practice behind a locked door. But they’re a little overprotective of their record because they’re proud of it and because of the 18 months of hard-rock labor that went into its creation. “We probably wrote enough songs to do a second album and then a third album,” Shinoda says. “The songs that aren’t on this album—I hope that no one ever hears them, because they’re awful.”

If you’re one of the millions who purchased Hybrid Theory, the songs that did make the cut won’t disappoint—there’s plenty of rocket-launcher guitar, pounding hip-hop beats, and moody electronic frippery. The album’s not a departure—when your last record went platinum eight times over, just try convincing yourself, or your record label, that a departure is a good idea. But it’s definitely an improvement. While Hybrid Theory’s rap/metal sound clash was sometimes awkward, the new album’s jagged edges fit together with jigsaw precision. “Hit the Floor” could be a Rage Against the Machine hockey-barn burner produced by Dr. Dre; on “Breaking the Habit,” Bennington emotes like a Pet Shop Boy over stuttering, proto-jungle beats. And although Bennington and Shinoda’s angst springs eternal, their writing has matured. When Shinoda barks, “I took what I hated / And made it a part of me,” or when Bennington pleads, “Let me take back my life,” Linkin Park sound like the most likely to chuck nü metal’s bad-childhood baggage and take off for someplace new.

***

Linkin Park began hammering out Meteora during Ozzfest 2001—after shows, between Halo tournaments, they would lay down riffs and melodies and half-finished songs on the Pro Tools digital-recording rigs they travel with. (“They convinced us that we should have a studio on our tour bus,” says Papa Roach’s Shaddix.) Shinoda insists that Linkin Park had “a lot of fun” while rolling with Ozzy’s dark caravan, but it’s clear that he and his bandmates view the extracurricular aspects of rock—the drinking, the groupies, the dwarf-tossing—as a necessary evil.

“Even when I was in high school,” Shinoda says, “parties were like, everything is just so played out. You go, people are drinking, people hook up, you talk to the same people who say the same stupid crap. It’s boring. And rather than do that, I could go hang out with my friends and write a new song. And who knows what that’s going to be like?”

Back home, they started arranging and rearranging, rerecording, micromanaging. Linkin Park never jam. “There’s something to be said for doing it that way,” Phoenix says, “but for us it’s just counterproductive.” Instead, they come up with ideas alone or in pairs; the collaboration begins in the studio, where ideas are tweaked and focus-grouped until everybody’s satisfied. “If one person’s not happy,” Shinoda says, “you gotta go back and start over.” The fact that Meteora sounds like an actual rock band playing together in an actual room, is, ironically, the product of endless clicking and dragging, endless discussion, the kind of ego-destroyingly, brain-meltingly democratic collaboration you’d think would drive even the closest-knit group of musicians utterly batshit.

“When Joe and I were in art school,” Shinoda says, “you’d put your stuff up in front of a class of 30 kids. And some people’s criticism would just feel so bad, so wrong, because you knew they didn’t really care about your or your work. Here, you’re dealing with six guys who really care about each other.”

Even the lyrics—which Shinoda and Bennington write together, usually after the music is finished—are put to the test. For the track “Somewhere I Belong,” Shinoda says, “we tried 40 choruses. It was just agonizing—you can’t even imagine writing ten, and we were writing the tenth one, and in our minds, it was done. And people would come in and say, ‘Yeah, it’s cool.’ and that’s not the response you want. You want, ‘That’s the greatest thing I’ve ever heard!’ In our heads, we were thinking, ‘Damn it—we gotta go on writing.’”

Linkin Park prefer to talk about their music this way, in terms of envelope-pushing and creative bar-raising and the satisfaction of a job well done. They don’t disclose other details, like what (or who) the songs are actually about. They would rather talk about how the songs resonate with the fans, the people who come to the meet-and-greets and pass them long letters about how Hybrid Theory kept them from running away from home, kids who don’t just dig the songs but really rely on them. They would rather talk about the girl who got through eight hours of brain surgery with help from their record. “They can’t do the surgery when the person’s knocked out,” Shinoda explains, “so they ask her, y’know, ‘What do you want to hear, to keep you up while we’re doing this?’ And she said ‘Hybrid Theory on repeat.’ And that was it.”

“For eight hours.” Bennington says, “that was what she listened to. And like, four hours into it, the doctors are like, ‘Okay, we gotta change it.’ And she was like, ‘If you change it, I’m falling asleep.’”

***

By design, your average Linkin Park song contains very few pronouns, aside from the narrative “I” and the all-purpose, unspecified “you.” Bennington and Shinoda write by talking about their own experiences, their own feelings; but as the process progresses, they ruthlessly strip away anything that’s too specific, anything somebody else couldn’t identify with, digging for the universal emotion that anyone could take and use if they needed it.

“There are a lot of weird things that go on in our culture,” Bennington says, sitting down to lunch at a cheese-steak place around the corner from the studio. “A lot of girls get sexually abused when they’re younger—that’s an epidemic in this country. And there’s a lot of kids who grow up without fathers. That’s why it’s hard to talk about the songs and just say, ‘This is what it’s about.’ because there are all these different things that can trigger the same emotions—getting kicked out of school, having your parents get divorced, or losing a boyfriend. All of those things can trigger anger, depression, aggression, self-doubt. When I’m writing, I’m constantly thinking about myself, because it’s the only experience I have to draw on. And I don’t see an exact reflection of myself in every face in the audience, but I know that my songs have validity to them, and that’s why the fans are there.”

Bennington may be the only true rock star in this unassuming outfit. Everyone else is around 25 and seems younger. Bennington is 27 and seems older. He’s from Phoenix, not California, and he’s the only member of the group that auditioned for his slot; to some extent, he still seems like the adopted kid in this band of brothers. When Shinoda talks about Linkin Park’s music, it’s in the passionate but sober terms of a young CEO. When asked which bands inspired him, he names Run-D.M.C. and the Beastie Boys and then U2 and the Police. Perfect—raucous rap-metal and life-affirming, messianic arena-rock sweep. Bennington cites Depeche Mode and the Smiths, misfits who sang about other misfits, about being freaked out by their bodies and their hearts. It was Bennington who told an interviewer early on in the band’s career that he’d been sexually abused as a child, then saw many of the journalists who wrote about the band interpret their lyrics through that prism.

The last part may explain why the members of Linkin Park are so cagey when they talk about themselves, why it feels like you could shake them by their ankles until their chain wallets fell out of their voluminous pants and still extract no personal details. It may also explain why, at one o’clock in the afternoon on a sunny Wednesday, Bennington is talking about the importance of honesty while wearing sunglasses. Indoors. He and Shinoda are a study in contrasts. Shinoda is stocky and Japanese-American and wears his fitted baseball cap low, covering his eyebrows. Bennington’s got nothing on his head but five o’clock shadow. There’s a distracting divot in his lower lip where the little golf-tee spike he usually wears is supposed to go. His black hoodie and Dickies shorts hang off his slight frame. In conversation, Shinoda is articulate and precise; Bennington’s the same, but there’s a sense that he’s keeping a less sedate energy in check. Shinoda seems like the kind of guy who organizes his sock drawer by color; Bennington seems like the kind of guy who organizes his sock drawer by color because he won’t be able to sleep otherwise.

They’re very different people, but they agree on one thing: They don’t want anybody—even their fans—to know that much about who they really are.

“I understand the impulse,” Bennington says, “but—”

“Think about when you were younger,” Shinoda says. “I used to think, y’know, ‘I wonder where Bono lives.’ And I’d wonder what it was like to be on tour and all of that, because that, to me, was like the most exciting thing.”

“I never really wanted to meet anybody that I idolized,” Bennington says. “I didn’t want my image of them to be altered if they didn’t live up to the craziness I expected. I like mystery. You look up to somebody and their music—there’s a mystery that surrounds them. If the mystery’s gone, it’s not as fun. People don’t want to imagine anymore—they want all this information, they want to know what everything feels like.”

Back at the studio, later that afternoon, Bennington is sitting outside on a folding table, limbering up his vocal cords with a Camel Light and talking about the album. “I think there’s a definite hint of optimism that wasn’t there [on Hybrid Theory]. Meteora’s still a dark record, but it’s a different kind of dark. It’s not pitch-black—there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.”

In the 2001 cult movie Donnie Darko, a blow-dried blowhard of a motivational speaker (played by Patrick Swayze) calls the perpetually seething, death haunted Donnie an “anger prisoner.” The scene’s a joke, as anything involving Patrick Swayze inevitably is. But the phrase sticks with you—it’s what Linkin Park sounded like on Hybrid Theory, and it probably describes many of the people who buy their records. Bennington hasn’t seen the movie, but he gets the concept.

“There’s this underlying anger in this country,” he says, “especially in young men. Nowadays, it’s not like you’re weird if you’re the only kid on your block who has divorced parents—you’re weird if your parents live together. And because it’s a relatively new problem, people don’t know how to deal with it, and a lot of kids feel like they’re misunderstood. And just the fact that we talk about these kinds of things lets people know that they’re not the only ones feeling this way and that it’s all right to question yourself and question the people in your life and to want to reevaluate things.”

Break’s over. Duty calls, and besides, Bennington has talked about himself enough for one day. He puts out his cigarette and goes back inside the rehearsal room, where his friends are, and shuts the door behind him. Back to work. For you, if you need him.