The thing about black narratives is that they never really solely belong to black people—their validity often depends on what use it is to a white audience. Black voices aren’t inherently flawed, of course; the biased transaction is woven into America’s fabric. There’s plenty of crystal clear expressions of black pain and disenfranchisement in modern culture, but it’s the listener’s decision whether to extend empathy—and, frankly, it’s much easier for white people to have surface-level interactions with such expressions in ways that merely leave them feeling cleansed. Having a strong African-American fan base is laudable, the old canard goes, but you’ll really have made it one you’ve crossed over. Vince Staples is keenly aware of this context, and even further so how it applies in the fickle age of the internet.

Staples isn’t only distinguishable for the wit that has won him acclaim outside of even the context of rap, but how he doesn’t really bother with pretending that the above dynamic doesn’t exist. He unapologetically skirts the expectations one would have for a socially-minded rapper living in today’s political climate: He ought to have some soliloquy on the uniting power of music, he ought to have plenty of commiserative quotes about the police state, and he ought to readily have poignant introspection on his lyrics. He rarely offers either in conversation, and it appears he’s made the conscious decision to go abstract. Vince’s debut Summertime ’06—a bleak look at survival in Long Beach—had a linear enough thesis to be summarized in its penultimate track. But there’s no such track on Big Fish Theory, a flooring Eurostep of a sophomore turn. The closest thing we get to a political manifesto is “BagBak,” where he disses the president and calls for more “Tamikas and Shaniquas in that Oval Office.” The rest is a collection of allusive experimentations chiseled by Vince’s laser focus.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=YeUOvrnOCVY%3Fecver%3D1

Big Fish Theory’s whiplash sonic shifts and industrial makeup will make comparisons with Kanye West’s Yeezus easy. However, it may have more in common with The Life of Pablo, which combined elements of Yeezus’ avant-garde structure with My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy’s tortured look at fame. Big Fish Theory doubles the ambition of Summertime ’06’s corroded soundscape but condenses that breadth within a tight 36 minutes. As a result, you get moments like “Yeah Right,” where Kendrick Lamar sprints through New York slang and a Dana Dane reference after a trance breakdown, and Ray J harmonizes within the deep house of “Love Can Be…” Gothic closer “Rain Come Down” unfurls like a soot-covered “Fade,” except with a more serrated baseline, spastic clatters, and less Post Malone (but more Ty Dolla $ign). Although Staples’ 2016 EP Prima Donna foretold this kaleidoscopic direction, Big Fish Theory’s production still manages to be bracing and surprising.

House and Detroit techno have both been tabbed as reference points for Big Fish Theory, so a music genre’s legacy in creating safe spaces for targeted peoples come as a subtext. But Vince’s preoccupation with death and the transience of Internet-era celebrity hasn’t softened all that much: The album is aware that after the bodies stop gyrating, the sun must come up. The contrast between the high-BPM liberation and Vince’s realism forms Big Fish Theory’s core tension. He temporary kills the drum patterns on late arrival “Party People” to lay that bare: “Move your body if you came here to party / If not then pardon me / How I’m supposed to have a good time when death and destruction’s all I see?” Juicy J hedonistically chants about “counting up hundreds by the thousand” on “Big Fish,” but suicidal thoughts aren’t that far in the rearview for Vince.

The fraught dynamic and the dizzying aesthetics make Big Fish Theory feel claustrophobic by design. This would be fitting from the viewpoint of a black entertainer cognizant of his expendability, especially one who was once trapped in a cycle of violence by both the state and rivaling gangs. The project slows down to a decrepit durge on “SAMO,” which finds the homegrown lethality giving way to his newfound decadence—he deadpans about high-priced couches before letting slip that “partner and ’em got bodies.” In a context where maximalism asphyxiates with only temporary pleasures, the threats ring darkly cathartic.

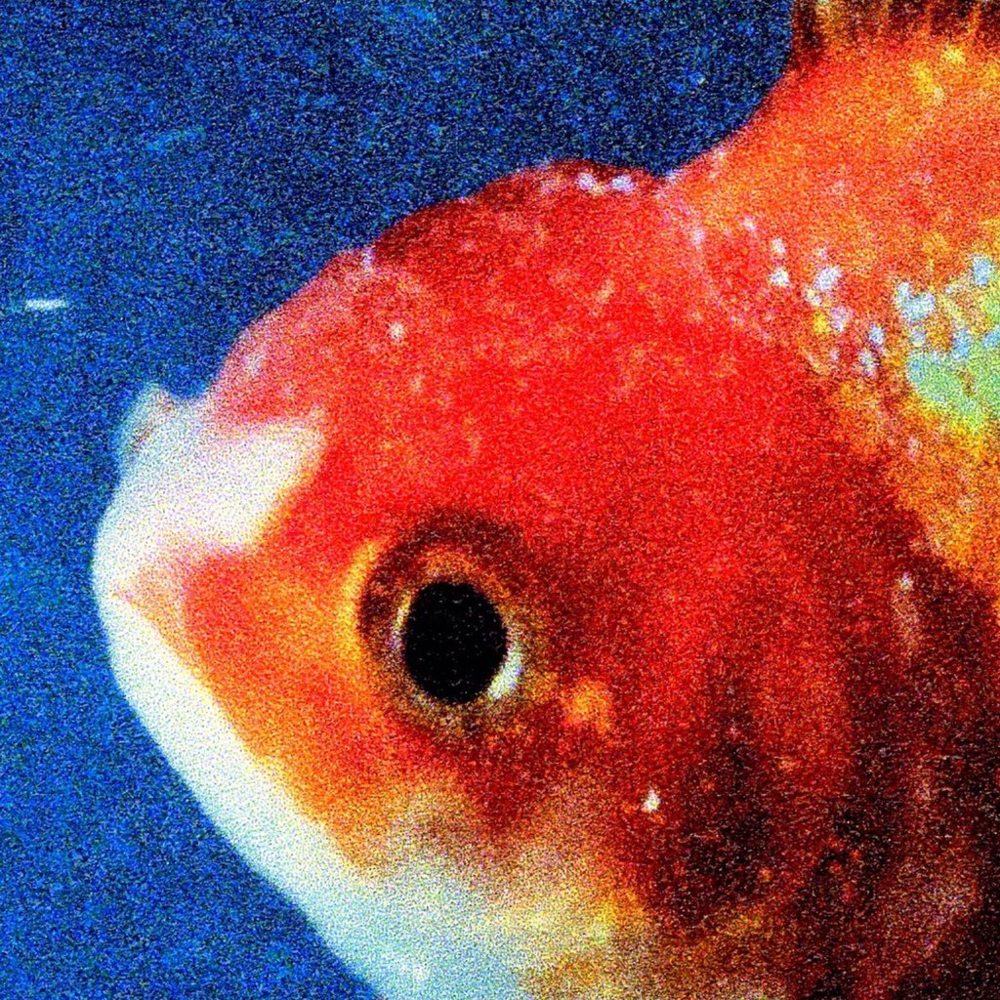

Although musings on high-life romance (like on “745”) feel too much like a side plot, Big Fish Theory further cements Vince Staples as a songwriter who can be thought-provoking and thrilling in equal measures. In an interview with Complex, Vince explained that the album title described, “Being larger than life in a smaller world, so to say. How rappers are perceived and perceive themselves.” The closest aquatic metaphor is perhaps a tank of fishes slowly drained of its water. They don’t accept death by lying prostrate; they spasmodically swim about for life. Big Fish Theory represents that sort of fight against suffocation, but with added neon lights.