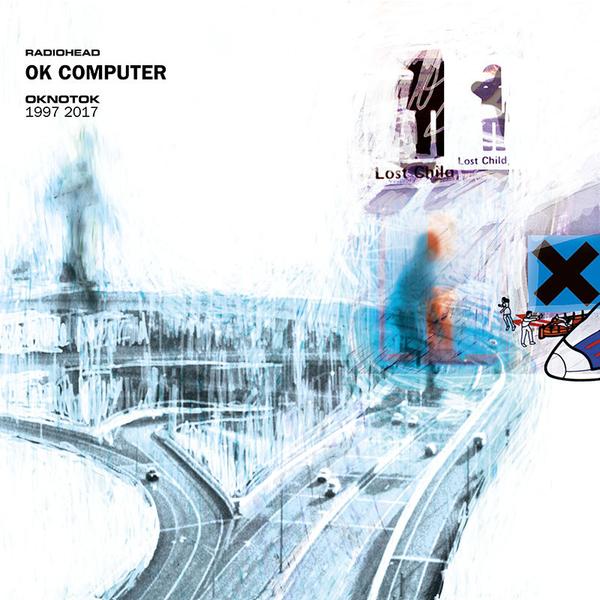

There was almost another album’s worth of material behind Radiohead’s most significant album OK Computer, and uniformly, it is good. One might expect that as many strong ideas were behind one of the most meticulously crafted and complex rock records of all time. Of Radiohead’s fairly rich back catalogue–from the glitchy Com Lag outtakes on the denser Hail to the Thief to the wayward experiments that pad out the Amnesiac “Collector’s Edition”— their 1997 leftovers are perhaps their most beloved among Radiohead devotees. Still, they’ve never been presented as a full unit, let alone bolstered and evened out on the mastering board to make them sound as monolithic as the actual album cuts. The recordings on the second disc of the OKNOTOK: 1997-2017 deluxe edition of OK Computer, which have all been previously available with the exception of three tracks that have mostly been disseminated in live bootlegs, sound like a live band playing identifiable instruments in rooms. Both the unified presentation and the enriched mix here exalts this material, selling it as a body of work relevant beyond the ranks of Radiohead superfans.

What is the succinct story this secondary group of songs tells? Some of the track sketch out chord progressions and stick to arrangements that feel like slightly like extroverted continuations of the guitar rock on The Bends (see “Pearly”’s gothic grunge). Then there are a few love letters to specific textures or instruments that would later become integral to the sonic universe of OK Computer (the misty synths and rickety jazz groove of “Melatonin,” a warped lullaby, or the staticy radio whistles of “Palo Alto.”) Most notably, there are several obvious could-be singles that seemed to create their own musical universes, but ones the band didn’t quite understand how to extrapolate on at the time. In their various stages of embryonic-ness, the B-sides and outtakes on OKNOTOK work together to create a world both related to and wholly separate from the grimmer, more cinematic one of OK Computer–something like a foreboding prequel.

There really only a few songs on the second disc of OKNOTOK that seem like they could have been easily slotted into the record after a little sprucing. “Man of War,” with its swimming, space-Beatles chording, doomsday piano and string adumbrations, sounds the closest–only a few overzealous Greenwood power chords tie it back to the band who wrote “Just” and “Creep.” It lacks the subtler surges of noise that became the main mode of emphasis on OK Computer, but has the same surrealist governing images: Our hero ends their obscure, murderous odyssey by “bak[ing] a cake/Made of all of their eyes.” The “Polyethylene (Parts 1 & 2),” a multi-sectional, perversely romantic epic that made for an apt B-side to “Paranoid Android,” of course, also had a close scrape with actually being included on the album. Included on this new, makeshift OK Computer Part II, its musical pivots jump-start the second side of the record nicely. When listening, it’s hard not to mentally fill in the gaps in the fairly straight-forward band arrangement, and wonder what it would have sounded like with all of the same otherworldly finishing touches of synths, static, and studio trickery of the songs that made the album.

There are also authentic hints on OKNOTOK of the future iterations of Radiohead: inroads to places the band knew innately they were not ready to go, perhaps. “How I Made My Millions,” which sounds most definitely like a demo, captures the exposed Yorke firing off flickering arpeggios on the keyboard that he would commit to in earnest on the band’s next several albums. “Meeting in the Aisle,” on the other, suggests a very different possible take on an electronics-based version of the band from the one that would soon come to be, fashioned in the vein of DJ Shadow (who would also inspire the drum manipulation on “Airbag”) and Massive Attack. You can hear the bent, nearly-atonal chording that would later show up on Amnesiac’s “Dollars and Cents”–an only half-fleshed-out idea that would prove fun for them to play for a lark once on tour fifteen years later. The funereal “A Reminder” stands as a bit of anomaly in the collection, reading like a morbid inner monologue from the depths of some retirement center; its bursts of spiritual-jazz keyboard and serrated noise tie it to the band’s recent arrangements on A Moon Shaped Pool.

The most storied and infamous songs in this collection have feeling of being something a bit too specific and broad-stroke for the universe of OK Computer, even as their pop prowess and peerlessness shines. Phil Selway described these songs to Rolling Stone as “the songs that I think people at the label were looking at thinking, ‘Yeah, there we go. That’s gotta work.’” It’s easy to hear why, but also why the band would abandon them. “I Promise” sounds like what it was for them: lovable at first, then an object of ire once they had to commit it to tape. Its impossibly addictive melodic hook is the kind no good songwriter would pass up, and know better than to complicate too much, but which would start to irk them after it was no longer just a sure bet on a tour setlist.

“Lift” also became an unsolvable dilemma in the studio, and, still, it seems a bit more staggering in the live videos than it does here, in the context of the other material they were working through at the time. In its particulars, it’s a striking, impressible pop-rock composition with a verse that is more crucial than its chorus, which was a bit of jeering sing-song that fit with the alt-rock of the time. The song made a hell of a lot of sense for a band contemplating a pop-rockier future and looking for some quick catharsis while opening Alanis Morrisette gigs, but next to the likes of “Exit Music (For a Film)” and “Lucky” on record, it no doubt felt intended out-of-context. But next to songs closer to its sensibility on OKNOTOK, it’s a testament to the band’s remarkable pop sense at the time–an inclination they, for their own neurotic reasons, quickly moved to complicate or subvert.

Reexamining the album next to its inspired runoff, there’s still precious little to say that hasn’t been said a million times already. But certainly, its themes gain a new life and weight when looked at next to these humbler, related sketches. The best part of the record was not the stock dystopian-imagery of a dissolute, slavish society, its malfeasant government and treacle-brained celebrities. It’s the unreliable narrators that espouse the disaffection and invests album with its singular energy–at turns manic, cosmic, and dilapidated. These ineffective dissidents prefer to privately stew over their TV dinners than try to change their situation; they experience their passing moments of bleak catharsis on cramped escalators, elevators, and on-ramps. The sleepy, Jonny-Greenwood-penned capstone for the album, “The Tourist” ends with a bell–the sound of a bleary-eyed traveler hailing the concierge at another sterile hotel. The song is, by Greenwood’s account, about families bustling around on mindless sight-seeing itineraries, but the lyrics just as easily conjure a lone figure on an interminable, Borgesian circuit of business trips. The bell, the final sound on OK Computer, suggests that the album has described a cycle that’s about to occur all over again.

There was little to nothing as picturesque and vivid in major-label rock as OK Computer in 1997, and it’s debatable if there’s been anything since. There’s a rough sense of timeline across its duration that enhances its effectiveness. The record begins with raging, despondent invectives suggesting angst specific to a young person (“Paranoid Android”) and saucer-eyed fantasies of escape (“Subterranean Homesick Alien,” with its synths that sound like starships taking off). But the outright panic gradually subsides; the album ends up with ruminations that seem to emanate from more broken-down, aging figures–the prole with “the job that slowly kills [them]” and the “local man with the loneliest feeling”–with reserved, more autumnal music to match. If OK Computer seemed to wither over its runtime, there is a more consistent, punchier quality to the second album sequenced out on OKNOTOK–full of big guitars, sweeping sentimentality, and drier wit. Here, its bold half-ideas, this many years on, sound better than ever, and find a new coherence.

https://open.spotify.com/embed/album/4ENxWWkPImVwAle9cpJ12I