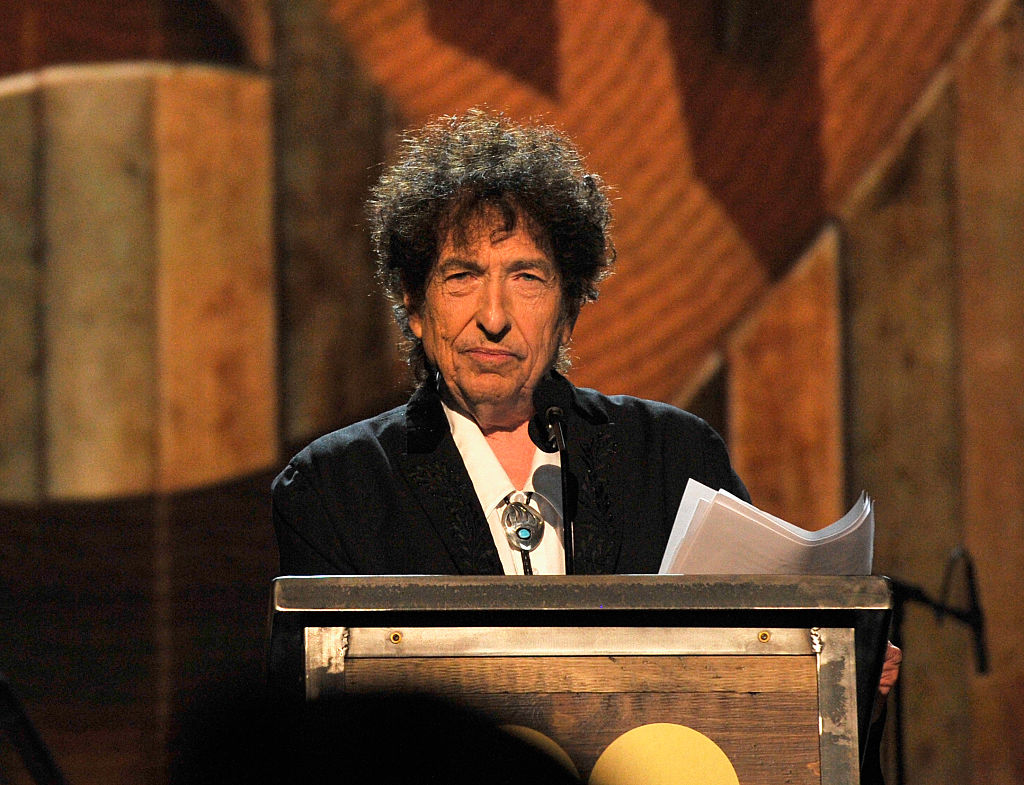

Over the weekend, Bob Dylan finally delivered the Nobel Prize lecture he had promised to the Swedish Academy. Giving a lecture is a requirement for Nobel Prize winners to receive their prize money of $900,000, and Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in October of 2016.

Dylan’s 27-plus minute speech explores, almost in epic-poetic style, a few works of literature whose “themes” made an impact on his songwriting. The project, he explained, was borne of spending time thinking about “how my songs related to literature…[to] see where the connection was.”

After an opening tribute to Buddy Holly and his early love of folk music (a form of music where “everything was a hit”), Dylan begins on the subject that forms a hefty chunk of the speech: Moby Dick. Dylan brings up religious allegories in its text, and the melting pot of cultures it drew from. He makes cryptic summations like “all visible objects are but pasteboard marks” while also basically running through the novel’s entire plot (prepare for spoilers if Moby Dick is on your summer reading list).

He precedes to All Quiet on the Western Front, which he calls “a horror story” He retells the protagonist’s tragic life story in the second-person: “Once you loved life, and the world, and now you’re shooting it to pieces.” Ultimately, he explains: “You’re so alone, and then some shrapnel hit into the side of your head, and you’re dead.” His thesis: “I put down this book, and closed it up. I never wanted to read another war novel again.”

He then runs through the plot of The Odyssey, which he calls “a great book, whose themes have worked their way into the ballads of a lot of songwriters….’Homeward Bound,’ ‘Green, Green Grass of Home,’ ‘Home on the Range,’ and my songs as well.”

After the body of the speech ends, Dylan asks “What does it all mean?” But then he seems to object to the question categorically:

“If a song moves you, that’s all that’s important. I don’t have to know what a song means. I’ve written all kinds of things into my songs, and I’m not gonna worry about it–what it all means. When Melville puts all his Old Testament doctrines and [many references]…in that story, I don’t think he would have worried about it either–what it all means.”

After recalling how Odysseus wanted to return from being “a king in the land of the dead” to “being a lowly slave to a tenant farmer on Earth,” Dylan used this idea to describe his own concept of songs versus literature: “That’s what songs are like, too: Our songs are alive in the last of the living. Songs aren’t like literature. They’re meant to be sung, not read…And I hope some of you get the chance to read these lyrics the way they were intended to be heard, in concert or on record, or however people are listening to music these days.”

Yes, it sure seems like Dylan doesn’t really think it made sense to give him this prize. Still, he’s taking it, and wouldn’t you? Listen to Dylan’s entire speech, backed by faint lounge-jazz piano, below.