It was 1985. My life sucked.

I was 25, barely employed, and suffering for my art.

My adopted hometown, Seattle, was deemed “the most livable city in America.” Livable? Maybe. Boring? Totally. Remember, this was the ’80s.

Like so many of my peers, I fancied myself a pop star. It was—at the very least—a palatable career option. I put in the requisite time strategizing and navigating. Perseverance would carry me through every hurdle.

Also Read

Every Soundgarden Album, Ranked

And why not persevere? What else is there to do?

In an uncharacteristically shrewd move, I took the duties of hosting a local music hour on the University of Washington’s KCMU called “Audioasis,” which had a small but loyal listenership. I figured this would provide me with the perfect opportunity to debut my band’s demotapes. But the phones didn’t exactly light up.

One afternoon I received a message from proprietor of a tavern called the Fabulous Rainbow. In a stroke of managerial savvy, she decided that Tuesday nights should be local music showcases. Because of my new affiliation with the local music community, I was able to sleaze into the job of Tuesday Night Booking Czar. Keeping my own charitable instincts in check, I played hardball. I said I’d take on this responsibility only if I were compensated with all the beer I could drink. A deal was forged.

At the time, the local tavern rock scene was dominated by granola R&B with an occasional serving of loopy new wave. Metal ruled the burbs to the east of Lake Washington. Most of the early bands who would later be associated with the embryonic “Seattle sound” were still playing at Gorilla Gardens, an unsavory all-ages club.

On a fellow DJ’s recommendation, I booked two of the latter bands into the Fabulous Rainbow. When referring to the headliner, my cohort ping-ponged between classic rock hyperbole (“They’re God!”) and reverent understatement. My curiosity was piqued.

Judging by the headliner’s name, I would’ve expected navel-gazing hippie jams. Soundgarden. It sounded a little too manicured. The first thing I remember about the band was recognizing its guitarist. He was also a DJ at KCMU. I never would’ve pegged him as a musician. Kim Thayil hadn’t yet transformed into a Metal Guru. He opted for an anonymously collegiate look—Prince Valiant haircut and all. To see somebody so normal-looking playing such decidedly berserk riffage was scary. It was like Invasion of the body Snatchers—outwardly normal but with a secret agenda.

To this day, I remember the first Soundgarden song I ever heard (“No Wrong No Right,” recorded on Louder That Love.) I thought the singer was some white-trash jock—the sort that would have a field day kicking effete college students’ asses. He was too healthy, too unashamedly physical. The twee psychedelia of the Paisley Underground was ruling college radio at the time. Soundgarden was more like the PCP’n’Steroids Underground. It singlehandedly transformed my understanding of what rock’n’roll was and what it should be. The state of “alternative music” at the time (this was before the term became generic) was conceptual and elitist. Hardcore had become restrictive and bound in its dogma. British pop music had forsaken grit for a glossy artifice. The spontaneity and menace that made rock’n’roll so liberating and sexy had been bred out of it. Soundgarden brought it back to life. It didn’t know any better. But it’s never been about what you know, it’s about what you feel. Soundgarden plays soul music.

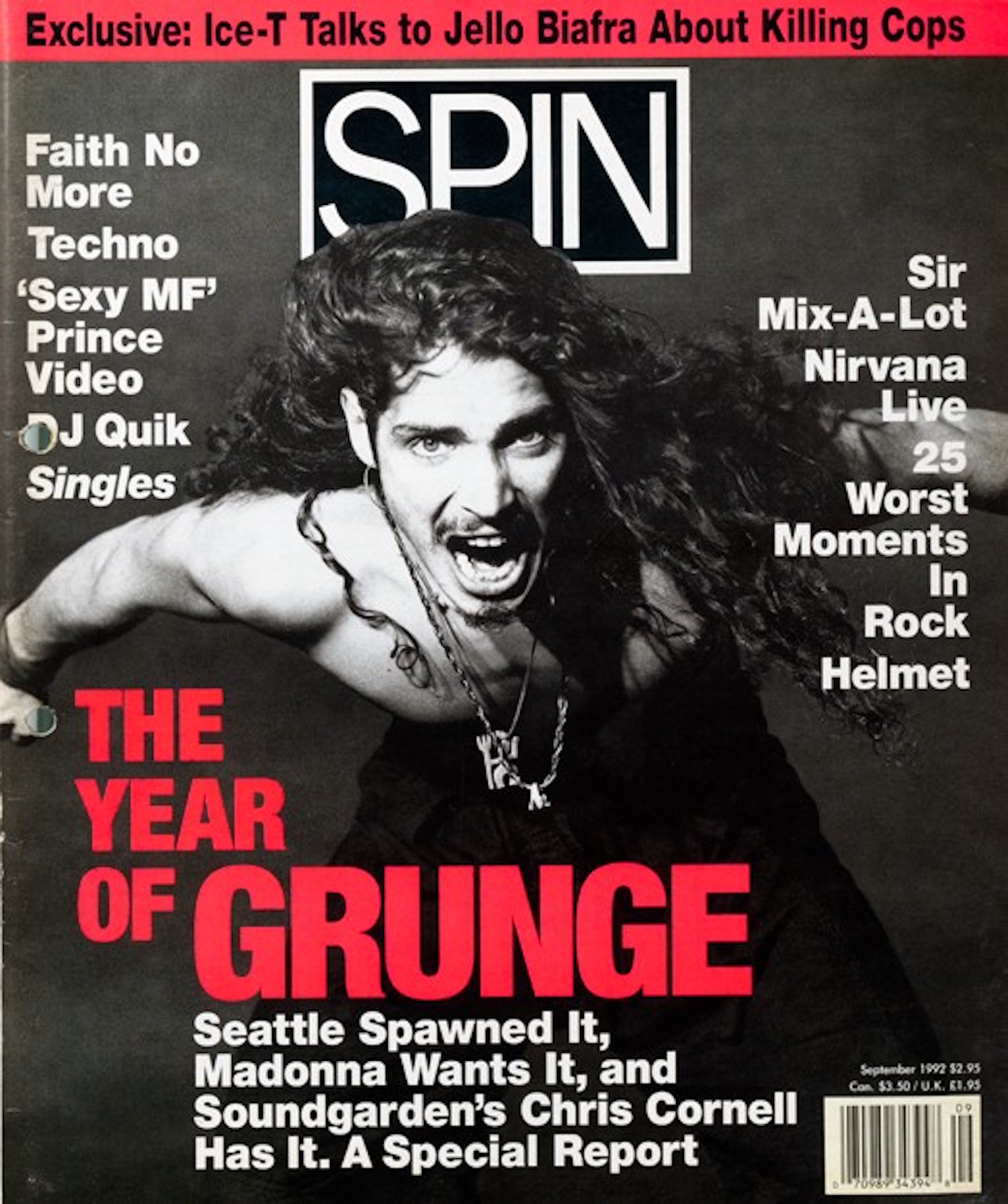

Luckily, it’s also a band of very thoughtful and intelligent people. Taking a couple of hours to talk with Chris Cornell reinforced my belief that you can stay true to yourself and not be rendered a basket case in the process.

SPIN: Going back in time… Soundgarden recorded its first EP, Screaming Life, and major labels came knocking. Instead of jumping to one immediately, you recorded your first full-length album for the SST label—I’ll forgive you—but what was happening back then?

Chris Cornell: Initially, when Soundgarden formed, we thought it would be great to be on SST, but most of those bands were friends of friends or something, so we resigned ourselves to the fact that it wouldn’t happen.

[Note: It was Soundgarden’s friends Screaming Trees who brought the band to SST’s attention.] The strange thing was that Soundgarden was kind of the hype band; I mean we were getting worried about being talked about too much. It was the first time a band out of the scene was getting that much attention. Like the Rocket mentioning that someone from Warner Bros. and A&M had come to our show—that was huge news because we hadn’t really released anything yet. We went just putting out Screaming Life and I think that level of attention of really good for us. Then other bands took some of the focus, which was good as far as we were concerned. I mean, when we put out Ultramega OK, it was at the time when a lot of other bands were starting to do really well. That was round Mudhoneymania happened and the very first demos of Nirvana were heard.

SPIN: When did the shakedown of major-label interest finally catch up to Soundgarden?

Cornell: When we were mixing Ultramega OK, we were still being courted by A&M and Epic. They were the only labels left after all of our dodging that still had the patience to pursue us. Because we didn’t think a major label really knew how to reach the market that we figured would be interested in our music.

SPIN: Do you think the time is coming where major labels will be able to compete effectively with grass-roots indies in discovering and marketing grunge bands?

Cornell: The thing for alternative bands now—I mean as alternative as we were when we were starting out, or any band on Sub Pop starting out—is that there’s no longer a market that major labels can’t reach and turn into mainstream music. So basically, while we were maintaining a career on an independent label, it was partially because we were afraid to take the step to a major and didn’t want to fuck ourselves, or be put in a position where somebody was trying to get us to do something we didn’t want to do. The other reason was necessity, because we were not a commercial band, and there was no commercial audience for us then. Now there is an audience for alternative. That was created by a healthy independent scene proving it. Major labels hired people from indies, people who worked at mom-and-pop record stores. And now a lot are execs at major labels. It’s a different world.

SPIN: You’ve said that you don’t consider Soundgarden a commercial band—with all respect, Badmotorfinger has almost gone platinum—that’s not commercial?

Cornell: No, it’s not. It’s not Top 40. I mean, we get a lot of radio airplay, but the only thing you could say we got in terms of commercial airplay was MTV, which wields power. But ultimately, we’re not the Black Crowes, we don’t have any multiplatinum records under our belt. I mean, honestly, we don’t write accessible pop songs.

SPIN: But you play huge arenas, and 750,000 sales ain’t chopped liver, my friend….

Cornell: It still doesn’t necessarily elevate you above a cult band. I mean, there were a lot of bands in the ’70s that weren’t considered commercial bands but had gold or platinum records and toured all the arenas.

SPIN: Is Soundgarden wary of releasing pop songs?

Cornell: No, I mean, I write pop songs, but those songs haven’t ever necessarily been Soundgarden songs. Our biggest single was “Outshined,” which I feel was a stretch for MTV and for FM radio, the two places that had never really played us before. That was definitely the poppiest side of our band, aside from “Big Dumb Sex,” which, apart from the language, was probably the poppiest song we’ve written.

SPIN: Has the musical climate of the universe changed so that people accept alternative music more easily?

Cornell: Well, where things are now, in comparison to where things were when we started, is that I think we could’ve switched Louder Than Love with Badmotorfinger and it wouldn’t have made any difference at all in terms of sales. I think we could’ve switched songs from Badmotorfinger and Screaming Life and I don’t think it would have made any difference. I think it has less to do with the songs on the record or the production and more to do with just being a band and continually making records, slow process. There’s definitely a huge escalation in fans, but not like the fanaticism that other Seattle bands have seen.

SPIN: Are you conscious of writing a song that would be considered the next big hit, for instance, another American anthem like “Smells Like Teem Spirit”?

Cornell: What ends up becoming a Soundgarden song and record is definitely a collaboration between all four members, not just what the individual member put in, but also what the four members take out. So songs come in and songs go out. First of all, I don’t think, if you want to use Nirvana as an example, that any band, whether it be us now or any band at any time, could plan on writing a song that catches fire like “Teen Spirit.” If you tried, you’d fail. What happens for me is the creative process continues, you write songs that you enjoy, you go into different fields musically because you’re bored with the last thing you did or you’re bored with what everyone else is doing, and something might jump out of the sky. That’s sort of how we’ve always approached it. There’s never been a time when we had a really popular-sounding song that we felt was really good but we just didn’t do it because ti was pop. “Big Dumb Sex” was, to me, one of the hookiest songs I ever wrote, but I don’t know whether I would’ve written a song like that for Soundgarden if it hadn’t said “fuck” 35 times in it, because it was making fun of that kind of music, really. The point is that I could write a song that is pure pop, but would it feel right for Soundgarden? The whole idea was that we don’t change for the marketplace as it exists, we just continue to exist until the marketplace changes for us. And I think that the marketplace has changed a lot.

SPIN: Do you think all the media hype surrounding Seattle is causing people here to become deluded? Is there a connection between the hype and the proliferation of a destructive rock’n’roll-style in Seattle?

Cornell: One guy asked me if Andy Wood [singer of Mother Love Bone] dying of a heroin overdose sort of burst the euphoric bubble of the Seattle Emerald City rock’n’roll scene, and, to me, out of most of the scenes going, Seattle was one of the more realistic and cynical. I don’t think there was a euphoric bubble to burst. There definitely may be now. The Melvins, Malfunkshun, Green River, and Soundgarden, I felt, were the core of what the word grunge is supposed to mean. I think all those bands or members of those bands are out somewhere else. The fantasy is that you’re going to run into Mark Arm on the street, and you’re going to go see TAD one night, Mudhoney the next night, Soundgarden the next night, then Nirvana after that. That’s not really the case. But I have to admit the first time we ever went to Austin, we were under the impression that maybe we could see the Big Boys or the Butthole Surfers. So I can’t really blame people for thinking that.

SPIN: What about all these Northwest bands dissing each other? Like Nirvana with Pearl Jam, and so on.

Cornell: When we were starting out and playing shows with Green River and Skin Yard, there was always a certain amount of talking behind other people’s backs, you know, like “That song sucks” or “those guys are totally lame.” And we would say things about people who were obviously our friends and are still our friends. And people would say things about us. The only thing is now, when somebody says anything, it becomes national or international press. I think a lot of it is different bands getting sucked into the whirlwind press thing. When the Rolling Stone article came out, the interviewer wanted my feelings and my rebuttals to the point of saying, “Well, Mark Arm said such and such a thing about your band,” and I said, “Well, that’s fine with me.” Mark Arm isn’t the sole Soundgarden fan and whatever he thinks of my music doesn’t really have a lot to do with the people who appreciate it. And his answer to that was, “Well, who’s going to give Mark Arm a check?” Who gives a shit? My point is that it’s more often a situation created by the press that it is created by actual animosity between bands.

SPIN: You have a brief, but memorable, stint in the movie Singles; 1991’s Temple of the Dog release is finally taking off. Do you ever think of breaking out of Soundgarden for new projects?

Cornell: No, because we’re heading into the period we’ve always wanted to be in—actually making enough money to survive comfortably. Soundgarden is the thing I personally feel like concentrating on, because to me it’s not like we’re winding something down—now we’re ready to take a shot without worrying about hype. I think a lot of the decisions we made early on were smart ones in terms of just how we did it. Part of it is luck, because for some reason what we did naturally as musicians and songwriters has sort of come into it’s own in the marketplace. It could have easily been something people didn’t want to hear.

SPIN: Did your lame rookie interviewer forget anything?

Cornell: Well, they always say that the entertainment and restaurant industries are the only businesses that don’t sink during a depression or a recession. I’ve done both, and I recommend to anyone who wants to be a rock star, if that doesn’t pan out, become a cook.