“You’ve got to be willing to move on and upset people along the way.”

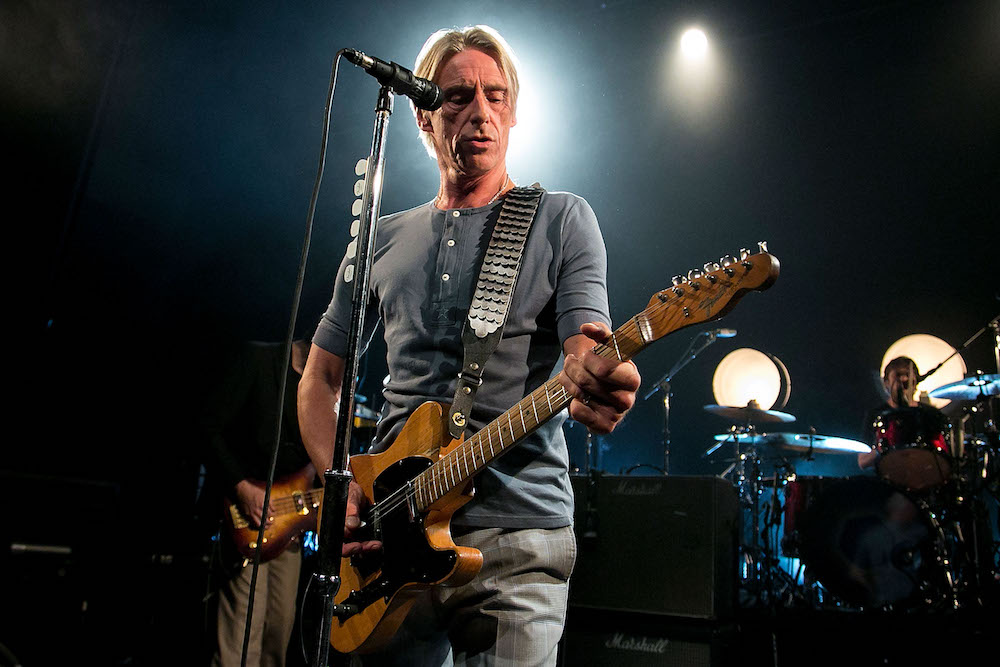

Paul Weller may have uttered these words in 2010, nearly two decades into his solo career, but they were his credo from the start. The Jam, the mod-punk trio he led, rapidly evolved from 1977 through 1982, leaving behind teenage rampages for sophisticated pop. When Weller pulled the plug on the Jam, there was no bigger band in the UK, but he was willing to ditch the success so he could pursue soul and politics with the Style Council. With Mick Talbot in tow, he spent the ’80s refining this bohemian idea, and slowly lost his audience. Polydor shelved Modernism: A New Decade, the Style Council’s reckoning with house music, in 1989, leading Weller to sever ties with Talbot and enter hibernation for three years. He re-emerged in 1992 with a lithe, soulful eponymous solo debut that set the pace for a career that’s been simultaneously reassuring and confounding, a career that is rooted in tradition yet pushes against the confines of convention.

Weller is set to release A Kind Revolution on May 12, this Friday. It’s his 13th studio set since 1992, which means he’s now released more records as a solo artist than he has with the Jam and the Style Council combined. This is a testament to his industriousness, to be sure, but also his restlessness, an attribute that’s often obscured by his reputation as the Modfather–the instigator of the ’70s Mod Revival who turned into the founding father of Dad Rock.

Such distinctions go unheard in the United States, where he’s nothing more than a cult act; his only solo album to crack the Billboard Top 200 was Sonik Kicks, which scrambled to No. 166 in 2012, and the only time he ever saw the American Top 40 was in 1984, when Style Council’s “My Ever Changing Moods” went to No. 29. Change is a constant for Weller. A decade later, he scored his first solo Top 10 hit in the UK with “The Changingman,” a single that turned the opulent art-rock of Electric Light Orchestra’s “10538 Overture” into meat and potatoes traditional rock.

This was a fleeting phase–he’d find a way to shake himself up roughly a decade later, when he reconnected with his experimental side on 2008’s 22 Dreams, kicking off an Indian Summer of creativity. But this conservatism not only was popular, it coincided with the rise of Britpop, a movement he could partially claim as his own. Because Weller did align himself with some of the retrograde elements of Britpop–he bought a house neighboring Noel Gallagher and anchored his band with guitarist Steve Craddock, leader of milquetoast luminaries Ocean Colour Scene–it can be tempting to pigeonhole him as a throwback, a musician who cherishes old-fashioned ways over modern sounds. Weller does have a few stodgy albums in his catalog–witness 1997’s Heavy Soul whose cover art replicates wood panelling, an undoubted allusion to how this is real music played on real instruments for real listeners–but it’s a mistake to think of him as a nostalgist, somebody who pines for the way things used to be.

Case in point: Weller refuses to reunite the Jam, even though it would rake in cash from both sides of the Atlantic. He’ll play Jam songs in concert–and he even appears on Back in the Room, the 2012 album from Jam bassist Bruce Foxton–but it’s clear that the trio is part of his history, not present. By dismissing the notion of a reunion, Weller makes it easy to divide his solo career from his original band but he’s always drawn from the past, covering “Slow Down”–a Larry Williams song he learned from the Beatles–on the Jam’s 1977 debut In The City and finding sustenance in the pastoral sprawl of Traffic on Wild Wood, the 1993 record that serves as the cornerstone of his solo career.

Weller didn’t have a smash hit with Wild Wood–“Sunflower” and “Wild Wood” hovered on the edge of the Top 10–but it didn’t matter, because it’s the album that illustrated how Weller seemed revitalized by reconnecting with the eccentricity. Sometimes, this weirdness can border on the conventional–this is especially true when he revives the heavy stomp of Steve Marriott’s Humble Pie–but the heart of Wild Wood is surprisingly funky and in a modern way, too. Like Paul Weller before it, he hired Brendan Lynch, a mixer on Primal Scream’s seminal electro-rock album Screamadelica, as producer, which meant the music was as conversant with electronic rhythms as it was with musty old records.

Lynch proved to be an ideal collaborator for Paul Weller and Wild Wood, and he midwifed Stanley Road, the 1995 blockbuster that established Weller as a commercial powerhouse, but that record is also where the formula started to calcify. Stanley Road and Heavy Soul had their moments–singles that kept him in the Top 10–but they’re conservative records, records that prize the trappings of tradition, containing explicit allusions to the Small Faces, Traffic and Dr. John. They’re albums that are all too happy to be part of a lineage of weathered long players. Because of their success–Stanley Road went platinum four times in the UK, by far his biggest hit–they still define his public persona as a real rocker. But Weller understood it was time for a change as early as 2000’s Heliocentric, where he attempted to mellow his music with Lynch. He bettered that formula with 2002’s Illumination, the first time he hired Simon Dine as a producer.

An ex-member of Adventures In Stereo, a project launched by founding Primal Scream guitarist Jim Beattie, Dine would wind up as Weller’s last great collaborator, coaxing out his inherent desire to experiment, but it took a while for them to get into a groove. Weller first had to flush out his retro tendencies with the 2004 covers album Studio 150 and mercilessly straight-ahead 2005 set As Is Now, but when he reunited with Dine for 2008’s 22 Dreams, he entered his second purple patch. A double album, 22 Dreams found Weller embracing his sense of adventure, channeling it into a silvery, shimmering mood piece; unlike so many of his records, it offered immersion instead of confrontation. He quickly snapped back to aggression with 2010’s Wake Up The Nation, a record that delivered its barbs through both muscle and skewed sonics, and 2012’s Sonik Kicks synthesized these two approaches, offering vivid, pulsating rock & soul.

With these three records, Weller got back to the fearlessness that propelled him through his first decade of work, but all good things don’t last. He and Dine fell out in a royalty dispute in 2012; then, he regrouped with the spacey 2015 set Saturns Pattern. But the new A Kind Revolution finds him opening a new chapter in his career, one that’s softer and straighter than his collaborations with Dine but retains a thirst for exploration, something key to all of his best music. A Kind Revolution isn’t quite in that category: it’s akin to Illumination, where he’s still searching for a way forward but the fact that he’s not content to recycle his old work proves that he’ll wind discovering a new path. If his career has proven anything, it’s that Paul Weller will always find a way to change himself into something new.