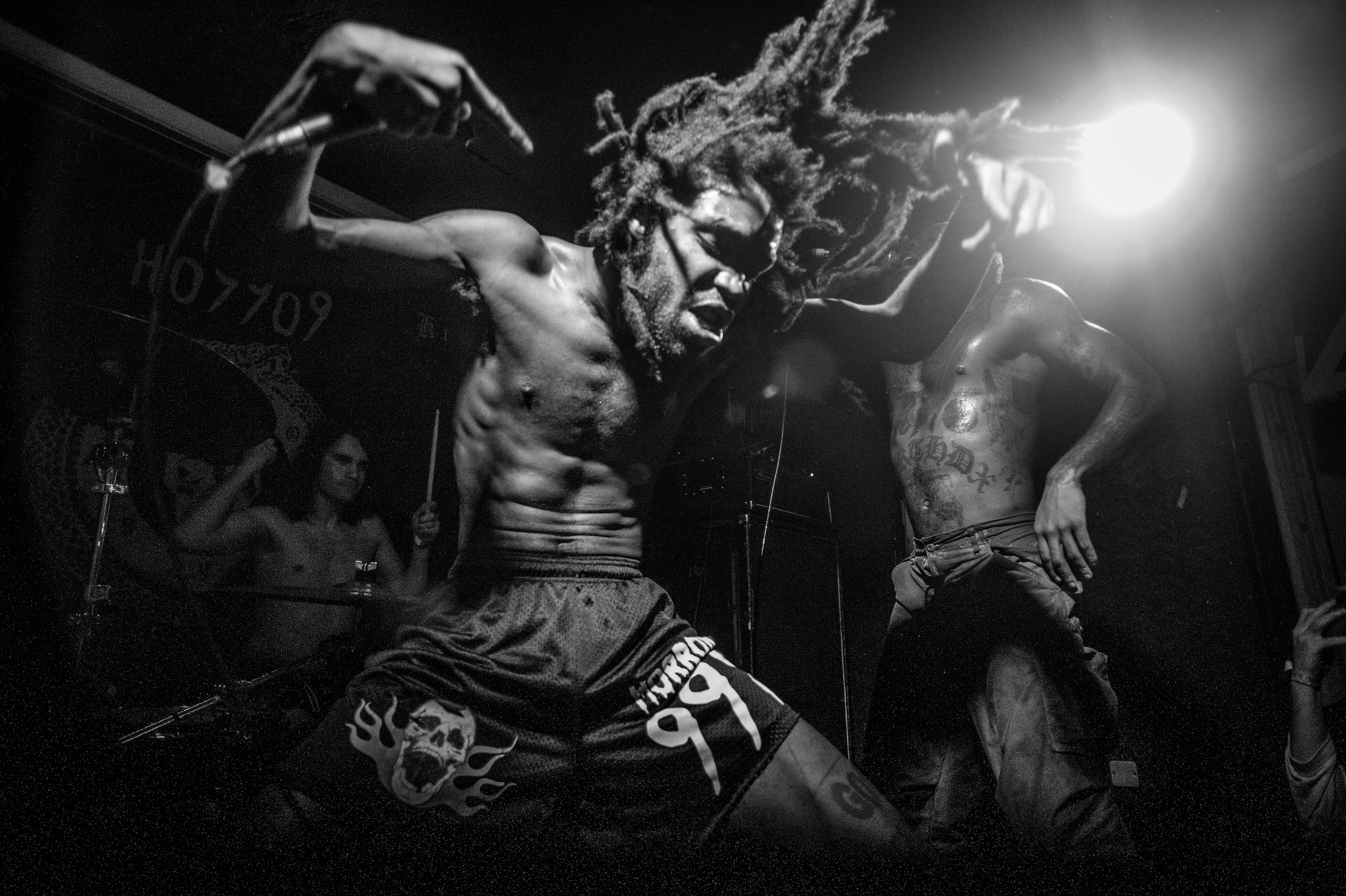

If a recent night in Brooklyn is any indication, the first thing you see at a Ho99o9 concert is their fans running for safety. As doomsday drones mark the New Jersey punk duo’s arrival, a wide space almost instantly forms in the middle of the audience. Nobody throws their elbows or tosses their bodies into the gap immediately, but the area elicits the same kind of urgency as an expanding sinkhole—leave now or get bodied. The panic happens before Ho99o9—pronounced “horror”are even fully visible on stage at the Williamsburg venue House of Vans.

Ho99o9’s well known love for chaos requires this kind of preemptive scampering. The band—comprised of members and co-rappers Eaddy and theOGM—became a news item at SXSW in March after a venue ended their set after two songs because the thrashing had become too intense. Years ago, Eaddy performed a show in Newark, NJ with his penis out. A couple of minutes before their House of Vans set, Eaddy teases to me that his partner theOGM regularly vomits as part of a pre-show ritual.

But the band’s performance on this cool April night ends up being comparatively tame. Eaddy, in his wrinkled schoolboy outfit (and fresh Vans), waves his mic stand around like a phallus, but his navy pants remain buckled. The shrimp tempura theOGM had eaten a few hours earlier stays in his stomach, though he does take the stage in a stained, lace wedding dress. TheOGM didn’t attempt Eaddy’s acrobatic leaps, but his howls echo as he flexes and poses with the same fictitious gravitas as a Dark Horse comic.

Their crudeness doesn’t exist only to shock, though—even the wedding dress has some metaphoric value. “It comes from the movie Kill Bill,” theOGM explains. “The Bride got killed and she woke up and came back and just struck vengeance on all her oppressors that fucked her over. It’s kinda like a rebirth. That shit inspires me.”

Punk—or punk-inspired—music has always relied on some oppressor to rally against, whether it be societal malaise or myopic venue management. Ho99o9 appear to have found their own antagonist after three years of one-off singles, EPs, and mixtapes of industrial dirges and sternum-breaking roars: the anti-black state. Their debut album United States of Horror is no less abrasive than the duo’s earlier material, but it’s a leaner collection that draws its focus from wringing righteousness out of Ho99o9’s instinctual aggression. “Street Power,” the concert’s opener, is a power-chord throttling proletariat wet dream (“Kill the rich / Cities burning up in flames”).

While Ho99o9’s distorted noise is protest in the way that black art within a disenfranchising society inherently is, theOGM and Eaddy spent the weeks leading up to U.S.H.’s May release making their politics explicit. They released videos for the title track, as well as “City Rejects,” and “War Is Hell,” which together form a trilogy that examines the effect commercialism has on blackness—how it trivializes human experience for money. Police officers kill black men in a pixelated video game, and later theOGM is seen chained and whipped—all to the delight of viewers who are shown watching behind the comfort of screens, their eyes replaced by $2 bills. TheOGM explains the latter is a direct reference to pageview culture. “The dude that’s on the two-dollar bill [Thomas Jefferson], he was a slave owner,” he says. “That’s all people see is dollar signs: ‘How can we make money off of this?’ or ‘How can we exploit this even more?’”

As multifarious as black art is, it co-exists within a construct that commodifies its creators, regardless of whether it expresses actual pain or if it’s branded as doing so. Ho99o9 isn’t free from this entanglement either. On the night I see them, Ho99o9’s raucousness takes place inside the walls of a venue created by a shoe corporation. Yet, theOGM and Eaddy are attempting to make a convincing case for being subversive artists. How does one separate radicalism from a simulacrum of it?

***

Ho99o9 inversely reflect on their stage personas in conversation. Offstage, Eaddy reins in his lewd kineticism, shrewdly gliding in his all-black attire through the orange glow of Blue Ribbon Sushi, a restaurant tucked in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, toward our table to converse in low-volume spurts. TheOGM’s dreads—an ominous, angular sight silhouetted against the House of Vans’ blue lights—are bundled into a large cap as he plops toward us a few minutes later, slightly more engaged and chattier.

They’re purposefully obtuse in the way you’d expect artists who swing wildly between impulses and conscious subversion would be. Neither reveal their full name or ages; when asked, only theOGM responded, stating via a publicist’s email: “My real name is, Blue James the 3rd, I’m 199 yrs old.” (Both are likely deep into their 20s, as they graduated high school in the late aughts). During our dinner time interview, I ask them, “Would you guys describe your aesthetic as punk?’”—echoing the descriptors that’s been attached to them. But the duo bristle. Eaddy mutters that they “don’t wanna put a label on it” before abbreviating his thought by sipping on his glass of water, silently motioning for theOGM to take this question.

“We don’t want nobody to be like, ‘Oh, well they make rap so why are they singing?’ or ‘Oh, they’re singing on this, so why are they now rapping?’” theOGM excitably responds. “No, I do whatever I wanna do, when I wanna do it. So there’s no genre values for us, you know? If I wanna make country music tomorrow, nigga, I’m doing it.”

https://youtube.com/watch?v=G8k4X-7JluI%3Fecver%3D1

Ho99o9’s cacophony is in line with other noted musicians whose transgressions fall outside the mainstream’s idea of black narratives, which is part of the reason why they’re often tagged with perfunctory comparisons. Legendary punk outfit Bad Brains are a common touchstone. Although theOGM’s howls sometime faintly recall H.R.’s wild oscillations, Ho99o9’s synthetic compositions are different, to say nothing of their politics. For one, they don’t quite share in their forefathers’ rastafarianism—in an interlude on United States of Horror, which takes place in a vehicle, the OGM says, “He could let this wheel go right now. God ain’t going to fucking grab the wheel and take us back home. Nigga, we gon’ crash.” They’ve been also compared to contemporary avant-garde enthusiasts Death Grips, and though Ho99o9 are stated fans of that band, their phrasing is far more legible than MC Ride’s cryptic lyricism. And if you let Ho99o9 tell it, they have no recent influences. Maybe Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN., but only in how theOGM says it “inspired me just to be better as a human.”

Rather, the molding of Ho99o9 can be traced back to Eaddy’s hometown of Newark, as well as theOGM’s time growing up in Elizabeth and Linden—both cities consistently rank among New Jersey’s most dangerous. Eaddy, who used to focus his energies on becoming an NBA player, repeats over dinner the fatalistic belief that he didn’t think he was going to make it out of Jersey.

“It’s the same shit for any young black person,” MoRuf, a friend and fellow rapper from New Jersey, says over the phone. “You either ball, your parents win the lotto, or some shit like that. Or you’re a rapper. I think the art is something that give us hope of getting out of here even to this day. Being an artist and a college graduate myself, it’s like, ‘Yo, we gotta get the fuck up out of here.’”

And so Ho99o9 invented their own escape—by the late aughts, MoRuf, Eaddy, and theOGM formed the NJstreetKLAN collective (more colloquially called JerseyKLAN) along with a crew of other artists. The clique sought to make a new space in north Jersey that combined punk and hip-hop culture in a town apathetic toward the former, even though the two genres have often rubbed up against each other. JerseyKLAN, in MoRuf’s words, represented the diversity of the culture geeks like “students of [Kanye West], the niggas who liked Little Dragon, niggas who were in Newark and liked skinny jeans.”

The crew would travel to the more fashion-forward New York City to buy fitted clothes, returning to the Garden State and its 3XL white tees. Because they weren’t being booked in their hometown, JerseyKLAN would also pool their own money to throw shows at hole-in-the-wall venues—Eaddy from his jobs at Urban Outfitters and as an YMCA pool cleaner, and theOGM from his stints a hospital security guard, a mall employee, and a host of other gigs. But by their account, the sacrifices weren’t for nothing—the other skinny jean wearers of New Jersey found out they weren’t outcasts, and in front of those audiences, Eaddy and theOGM honed their craft. Their first performance together in late 2012 at New Jersey’s since-shuttered venue the Metropolitan had the seeds of the raucousness they’d soon become known for.

“This dude was flying off of shit,” theOGM recalls of Eaddy. “Not even caring about what he was saying or if the vocals sounded good at that time. We didn’t even care. Even right now, I don’t have that much in my refrigerator,” he continues, just before his shrimp tempura arrives. “I’m still struggling. Everything comes from struggle, or frustration from not being heard. I mean, we’ve been making music for a while now and we’re just now getting a certain platform. Like, I can’t like scream in a dude’s face. But on stage, I can express that. It’s cathartic.”

***

In summer 2014, JerseyKLAN rapper J.Philippe was down in Atlanta figuring out what was next for herself. The collective had dissolved as its members grew up and went after their own separate interests, but she was still in contact with her neighborhood friend theOGM, who told her he was working on a new project, telling her, “I’m in a band, but the music, it’s different.” Ho99o9 was coming, and theOGM was going through a shift

“Not only did his sound change—everything about him changed,” Philippe recalls. “His style, the way he was dressing, the way he did his hair. He was definitely growing into his own person.”

A majority of theOGM’s pre-Ho99o9 material positions him as an acolyte of the Soulquarians. He can be heard rapping over Erykah Badu and Andre 3000 beats and other bohemian productions. The songs are pleasant, but his lady-wooing persona lacked definition. Ho99o9’s first single “Bone Collector”—which dropped a year after theOGM’s last Bandcamp project, 2013’s SummerChristmas—was a dramatic shift. After JerseyKLAN’s dissolution, theOGM’s soulfulness had corroded into something brutal: Rawkus Records-friendly instrumentals were replaced by metallic death stomps, and theOGM openly referenced the Death Grips (“Had The Money Store with a death grip”). Eaddy played the horrorcore anchor. “Bone Collector” has since amassed over 75,000 streams on SoundCloud, exponentially higher than their solo SoundCloud material, proving that this radical shift resonated.

Ho99o9 permanently moved to Los Angeles in 2014 and sparked the interest of TV on the Radio’s David Sitek, who heard of the duo through a friend. Sitek found a creative match in the Jersey punks and got to collaborating immediately. “I think that in a world that’s so calculated and based on the artifice, it’s really refreshing to see people reacting to the immediate and the now,” he says. “I’ve watched them summon the energy from nowhere. We’d be hanging by my house, which is near the trees, and then we’ll just make this gigantic apocalyptic [track].”

Sitek holds four production credits on U.S.H.: The anarchic rallying cry “City Rejects,” the scuzzy “War Is Hell,” the title track, and the castigating two-minute blitz “Face Tatt.” The former three establish the pillars of Ho99o9’s angst amidst a project that is admittedly not quite fully realized. The riffs are often too repetitive and lack a certain tension needed to make some of the band’s guttural noises feel earned. But there are key moments were the exasperation is palpable, like on the title track’s bridge, where theOGM fumes against police brutality, racism, and “motherfuckers abusin’ they power.”

It’s those bits of relatable rage that give Ho99o9 their vitality. “Fuck the police” could easily be a rote phrase at the hands of a lesser artist, but the anguish of consistently being an other is felt. Despite spending years working with mainstream averse art, it’s a trick Sitek can’t all the way express.

“I think to do something that’s raw and undefined and honest is an act of defiance these days because of how artificial everything is,” Sitek says. “If you’re thinking about yourself and what your place is, you’re not really being creative.”

There was no such double-thinking at the House of Vans. TheOGM, Eaddy, and their backing drummer Brandon Pertzborn are all shirtless as they head into the set’s final leg. At the night’s climax, the music quiets and Eaddy ventures out into the crowd toward the center of the ongoing moshpit and sits down on the floor, demanding onlookers to do the same. After a brief countdown, he shoots up and screams “get outta my way!” in a performative rage, darting back towards the stage and leaving the wild-eyed punks to have at each other.