In a profile of Vines frontman Craig Nicholls from a 2004 issue of Spin, Marc Spitz’s opening line was a quip about how he wanted to hit the guy. Though he eventually warmed up to the singer, Spitz was frustrated by how purposefully evasive his subject had been, even after putting in a substantive amount of time and effort to get to him. “There are al-Qaeda detainees at Camp Delta who are more likely to give up information,” was how he put it. It was a ridiculous comparison to draw while writing about a moody rock star struggling for relevance next to the Strokes and the White Stripes—but if you couldn’t treat music as seriously as anything else, what was even the point? As a reader, Marc made writing about music seem like a hilariously insane pursuit, best accomplished by those willing to put themselves in deeply awkward situations around their idols. He did it frequently, and he was great at it.

Marc passed away last week in New York City, and left over twenty years of music writing behind him. During his decade-long career at Spin, he penned some of the magazine’s most well-known features and covers—on Morrissey, Axl Rose, the Pixies, Trent Reznor, Weezer, and more—and was especially talented at treating celebrity, buzz items, and blind gossip as entryways to cultural criticism. (His 2003 cover story on the Strokes perfectly captured what kids in a post-9/11 downtown Manhattan would most readily rally behind.) He wrote 13 plays and eight books, including We Got the Neutron Bomb (the definitive story of LA punk), a Bowie biography, How Soon Is Never (a novel about two Smiths fans plotting their return), and Poseur, his memoirs.

I only knew Marc by legend and a few online messages we exchanged over the years. (When I was on staff the first time around, as an associate editor, I would find that he had beat me to publicists as “the Spin writer” covering whatever show I’d hoped to get into, even though he no longer worked here.) A few months ago, when I returned as editor-in-chief, he sent me a nice note and said that, though he had gone on to write for the New York Times and was a regular at Salon, he was nostalgic for his formative years. “I still feel like and will always feel like a Spin writer,” he wrote.

In honor of the contribution Marc had in making Spin the definitive critical voice in music journalism, we’ve digitized some of his most memorable stories and gathered tributes from his former Spin editors, writers, and friends. You will find memories from Doug Brod, Victoria DeSilverio, Caryn Ganz, Andy Greenwald, Michael Hirschorn, Chuck Klosterman, Sarah Lewitinn, Alan Light, Tracey Pepper, Rob Sheffield, and his longtime book editor, Carrie Thornton, below.

— Puja Patel, editor-in-chief

***

Caryn Ganz

There were a few things about Marc Spitz that were obvious: his posture, which at times was so convoluted it felt like his suit was simultaneously yanking him upright and trying to nail him to the bar; his talent as a playwright and profile writer; his ability to hang around with the right people in the wrong location just long enough to get the perfect quote.

And then there were the things that were less conspicuous: his generosity; his unending love and appreciation for music writing and writers; his respect for the lady editors of Spin (Sia Michel, Tracey Pepper, and myself) who hammered him into shape; and his incredible sense of humor.

Marc was hilarious on and off the page, if you knew where to look. His preferred medium was email, but he had a flair for AIM, too. You never knew what was going to come after that initial opening: “hey.” It could be something about hanging out with Courtney Love the night before, or an unsolicited review of a Jewel single that “made me wanna eat angel dust out of the butt of one of jon’s homeless goats.” (I can’t remember what he was referring to there, but I’m sure it made me laugh in 2003.)

He had a charming way of hassling me about his travel arrangements when I was an assistant (“oh and mostly all rental cars are automatic right? i can’t drive a stick… but i’ve been to jail so that gives me real man points, no?”), and asking for his interview tapes to be transcribed (“hey caryn, i have a tape here that’s very entertaining. if i was an intern, i’d be really into listening to it and maybe even writing out what it says. i swear there are only about six or seven more tapes. maybe ten. definitely less than 20.”)

His suggestions for Spin‘s first “List Issue” (when we sent up the idea of magazine lists by doing a full issue consisting of nothing but lists, and yes, this was before the internet) just scratched the surface of his talents:

Best “Life on the Road Is Crazy, Baby, and I Realize It’s Taking Its Toll on Our Meaningful Relationship, But I Gotta Keep Rockin’ With the Boys Just a Little Bit Longer” Song

– “Beth” – Kiss

– “Home Sweet Home” – Mötley Crüe

– “Mama I’m Comin’ Home” – Ozzy Osbourne

– “Faithfully” – Journey

Things Madonna Could Have Re-Sold to Us But Amazingly Ignored

1. Electroclash

2. Swedish garage rock

3. Bootleg mash ups

4. Madonna (circa ’83)

But my favorite funny piece Marc wrote was “Stick It Up Your Inbox!” in the June 2002 issue with Moby on the cover, where he imagined what Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake’s breakup emails were like. This was 2002—pre-texting, pre-Snapping, and before it became cool to think about Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake as a rock writer. He paid attention to the details, from the funniest timestamps and misspellings to how to work in a Tara Reid joke.

The Strokes stories, the Axl Rose cover, the boozy Backstage Pass columns: Yes, that was Marc. But this was Marc, too. And Spin wouldn’t have been Spin without him.

Ganz was a writer and editor for Spin from 2001 to 2006 and the editor-in-chief from 2011-2013. She is now the pop music editor for the New York Times.

***

Doug Brod

As editor-in-chief of Spin from 2006 to 2011 and as the executive editor for two years before that, I had the pleasure of collaborating with Marc too many times to mention. As anyone who read his work in Spin knows, he was a spectacular, passionate journalist, but his plays and books were often even better. I remember telling him that I devoured his first novel, How Soon Is Never?, in one day at the beach. He shaded his mouth with his hand conspiratorially (as he often did), emitted this weird cartoon snicker, and said, “Wow!” We Got the Neutron Bomb, the oral history he did with Brendan Mullen, is the essential document of West Coast punk. And his memoir, Poseur, is a compulsively readable, achingly honest account of his life in the rock ’n’ roll trenches, alternately self-lacerating and self-mythologizing. Though I didn’t know him before Spin, we grew up just a couple of miles away from each other and later bonded over shows we both had attended at the Jones Beach amphitheater and the Malibu nightclub. We’d also obsess over minutiae regarding WLIR (later WDRE), the new-wave/alternative-rock station that helped shape our music tastes.

Marc could seem—all right, he often was—petulant, bitchy, needy, aloof, and exasperating. But he was really a softie—shy, brilliant, funny, generous, awkward, kind, and not a little geeky. After leaving Spin, we never lost touch and would often meet for drinks at the Library, his favorite East Village dive. Over the years, I assigned him pieces for other publications I edited. In January 2016 I was putting together a David Bowie tribute magazine and needed Marc to write a biographical essay. He was in the midst of a huge book project, but six days later he sent me 4,500 nearly perfect words.

Marc last emailed me on January 6: “Happy 17. Anything cooking over there that might be up my tree? Still looking for gigs.… I have to tell you too about this musical I’m involved in. Picture WLIR meets well…Broadway.”

It breaks my heart that he never got to tell me about that show, but he left behind so much other work to discover and revisit that to complain would be churlish. And anyway, he’d likely make fun of me if I did. That was Marc.

Doug Brod became executive editor at Spin in 2003 and was editor-in-chief from 2006 to 2011. He is currently deputy editor at Condé Nast Content Development Group.

***

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225794″ title=”Can Prolonged Exposure to Enya Replace Happy Pills?” index=”” image_id=”225796″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225778″ title=”STICK IT UP YOUR INBOX!” index=”” image_id=”225779″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225951″ title=”Ask the Experts: Can ’90s Pop Stars Jump-Start their Lagging Careers? What Would Krusty Do?” index=”” image_id=”225952″]

***

Tracey Pepper

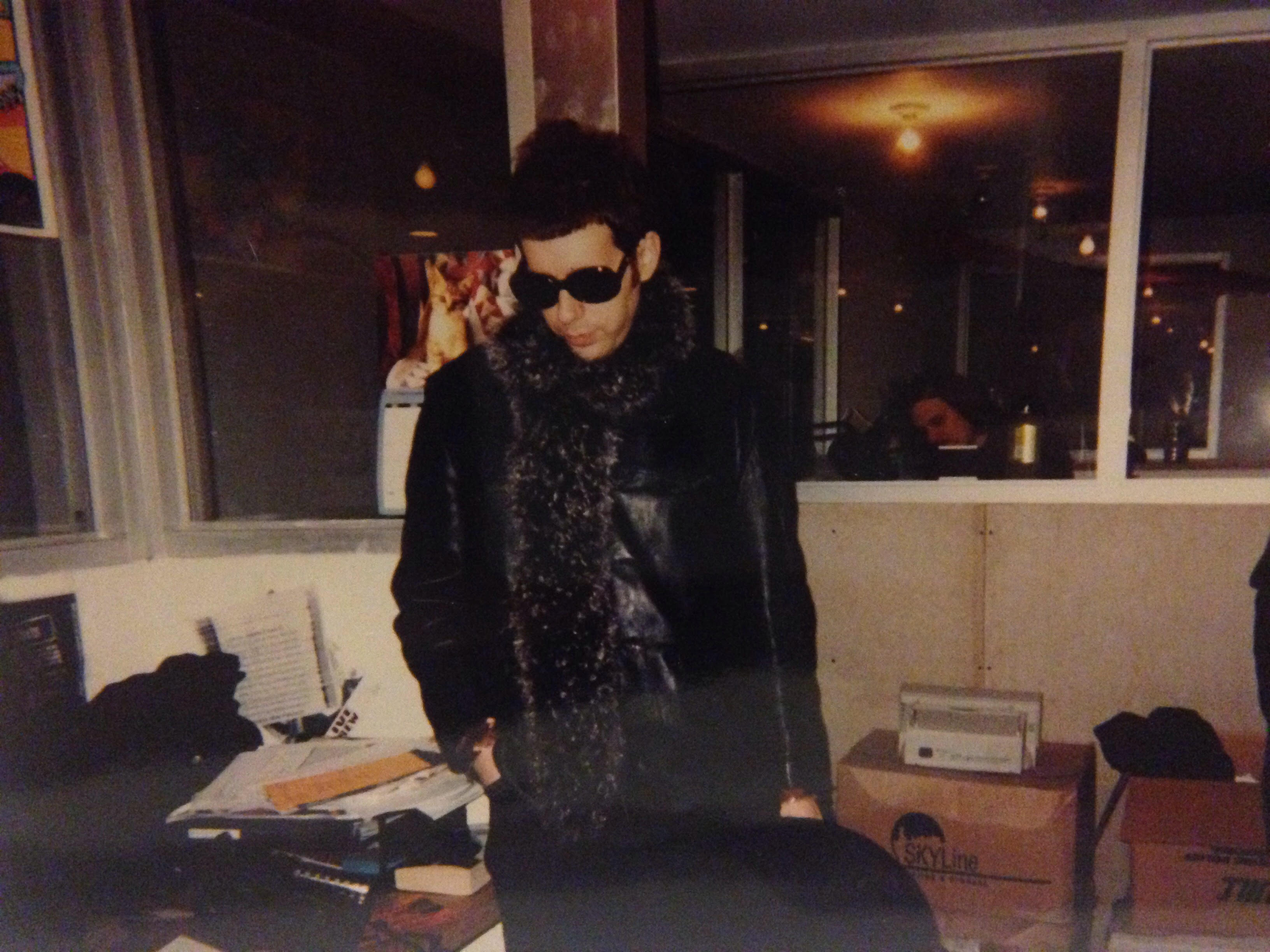

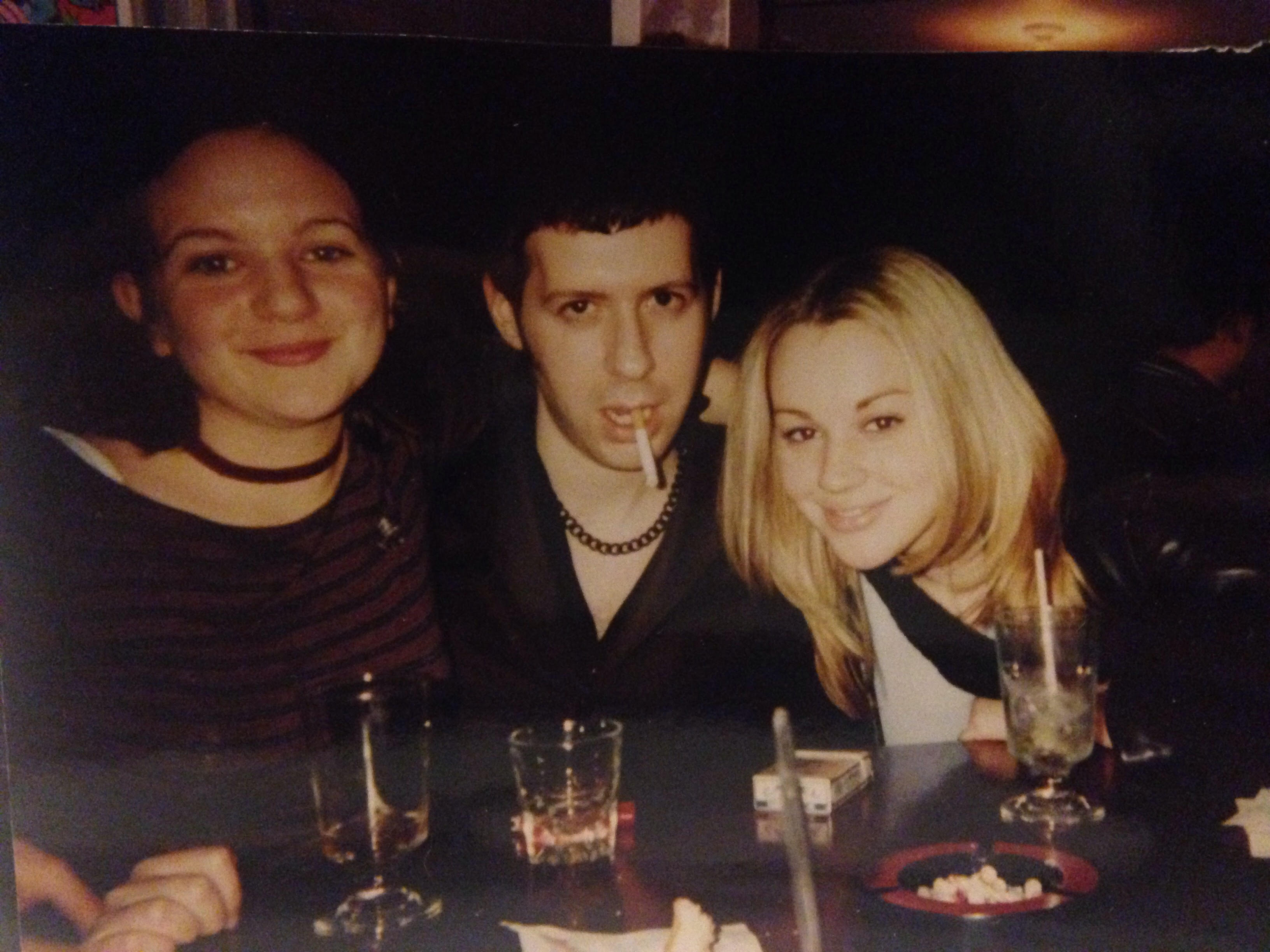

I met Marc in May 1998 when Michael Hirschorn and Craig Marks hired me to team up with Sia Michel to create a front-of-the-book section, Noise. Marc had started the year before and worked in the magazine’s online department. He was hard to miss. His standard work attire was a black suit and a pink feather boa. He wore black bug-eyed sunglasses indoors. He nearly always had an unlit cigarette in his mouth. As he recounts in his candid memoir Poseur, I thought he was a dick. He thought I was stuck up. It was not love at first sight. “But maybe we needed each other somehow,” he wrote. He could not have known how true that would turn out to be. Over the course of my seven years at Spin, Marc was my partner-in-crime. He filed hundreds of pieces to me – everything from “the most scabrous Jukebox Jury ever” (as Sia put it) with David Cross and John Mayer, to what he imagined Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake’s break-up emails looked like (also a gifted playwright, Marc wrote dialogue like no one else).

We spent all day, every work day chatting via AOL Instant Messenger (it was the ’90s). That’s how we brainstormed story ideas. Most of what we ran in Noise started life as a way of amusing ourselves or, at the very least, making Sia laugh. (We lived for that.) Even Marc’s throwaway ideas were gems. When an Enya box set arrived in my mail, he thought it’d be funny to spend four hours walking around New York City listening to all 50 tracks and reporting back on the effect it had on his nervous system. (“Feel guilty for wanting to hurt Enya.”) Or his “Ask The Experts” interview with Krusty The Klown, in which Simpsons’ writer Matt Selman, as Krusty, opined on how ’90s pop stars like Hanson, Billy Corgan, and Evan Dando could jump-start their lagging careers. (“You’re over, boychik. Finito.”)

Like most creative geniuses, Marc could be moody. We had our blow-out fights, most of which took place over I/M. He knew I was really mad when I gave him the silent treatment by logging off of AOL for a few hours. But he was often infuriating. He would file a thousand words when I only needed 250. He didn’t know what a nut graf was. He would refuse to use periods. Or he’d leave five spaces after the period. Or sometimes three. Or none. I made him write all my captions. (“You’re so much better at it,” I whined to him. “And it’ll take you five minutes.”) There was the time he slept through his interview with Oasis’ Noel Gallagher and I had to send an intern to bang on his apartment door. Or the time I begged him not to hit up Chris Martin for money when Sia sent him to London to interview Coldplay. Always short on cash, even though he made a bigger salary than me (an editor), and the only person I knew who never had a credit card, Marc was notorious for asking rock stars for money. Kid Rock once gave him $50 at Clive Davis’ Grammy party.

But for someone so outwardly cocky, Marc could also be endearingly vulnerable. I’ll never forget the day he called me at the office half an hour before he was to interview his idol Morrissey at the Beverly Hills Hotel for our May 2004 cover. He was a nervous wreck. “I can’t do it,” he said. “I’m leaving.” He meant it. I said, “No, you’re not. You can do this. You’ll be fine. The story will be great.” And of course, it was.

When I moved to Los Angeles at the end of 2004 and worked out of the West Coast office for a few months before departing for good, Marc was the one I was the most worried about leaving behind. Not one for sentiment, he wrote in the group going-away card: “You can operate from the Los Angeles office any time you like, but you can never leave (guitar solo).”

That was Marc. I loved him. It is an outrage that he is gone.

Pepper was an editor at Spin from 1998 to 2004. She is now a writer and media coach living in Los Angeles.

***

Rob Sheffield

I met Marc 15 years ago on Avenue A, at the Library bar. A sharp-dressed man stepped to the jukebox and played the Replacements’ “I.O.U.” and the Smiths’ “I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish.” I thought, hey, I bet that’s Marc Spitz from Spin. So we started arguing about the merits of Strangeways, Here We Come and never stopped. He became a major presence in my life—as a writer and as a friend, he had an energy level that was a challenge to match. He was extravagant in his warmth as well as his scorn. He was melodramatic and fond of scenes (and fond of melodramatic apologies for said scenes). When it was his turn to get a round he’d theatrically fumble through his pockets, a trick that worked on me for years. He could only write about things he felt passionately about; when he didn’t feel it, he couldn’t force it. He worked incredibly hard—he pretended to be slack, like how Robert Mitchum used to pretend he hadn’t learned his lines, but he’d drop out of sight for a few months and then emerge with a couple of new plays (Gravity Always Wins and Your Face Is A Mess are my favorites) or books (his love letter to New York, Poseur, or his love letter to the Smiths, How Soon Is Never, or his uniquely American bio of Bowie). Yet he could also dash out blasts of brilliance on the spur of the moment, like his fake Britney/Justin emails from 2002, which are so funny and nasty, yet also so strangely moving. He kept the same AOL address all these years just because he once used it to contact Robert Smith, and he wanted Robert Smith to be able to say hi any time. He was a true enthusiast and a friend. I will miss him.

Sheffield was a writer at Spin from 1988-1995. He is now a columnist for Rolling Stone.

***

Michael Hirschorn

The news about Marc thrust me back to a time that now seems like ancient history. The mid-nineties! For my son that feels as far away as the ’50s did when I was a child. Spin Magazine back then was like a cross between Withnail and I and Trainspotting, an (almost entirely white) rainbow of scrawny, ill-shaven, bright-red-lipsticked, tattoo-y music nerds whose intensity about rock n roll would seem entirely alien today, now that nerdism has been softened by a warm, slightly patronizing societal embrace. Spin employees, to my endless frustration and fascination, viewed every assignment, every edit, as the front line of a culture war. Was this a story they wanted to do FOR THE MAN? Would cutting this piece imply submission TO THE MAN? Nobody acts like that anymore.

Marc was the purest of these impure breeds, an angry twee-boy who was channeling David Johansen circa New York Dolls with the poetic haute-mope of his idol Morrissey, Lester Bangs by way of Gerard Cosloy, the nineties version of gender fluid (sort of)–every encounter was an opportunity to reject your false values and hopelessly compromised soul. His anger was thrilling, as was the sense of possibility around his talent–a talent that I think we all knew would constantly be undermined by his need to undermine it. Before Moby licensed every track from Play and officially sold out “alternative” in 1999, unrealized potential was the point of being indie; success represented failure, unless achieved on terms so specific as to be almost impossible. Marc knew this too, adding layers of “poseur” irony to what was a deliciously conflicted existence. That he died a “rock n roll death” may constitute, in the scrambled logic of his romance with rock n roll culture, the only possible kind of victory. It is also inalterably sad.

Hirschorn was the editor-in-chief of Spin from 1997 to 1998. He’s now the CEO of Ish Entertainment, a TV and film production company.

***

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225939″ title=”Appetite for Destruction: Axl Rose” index=”” image_id=”225941″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225527″ title=”Life to the Pixies” index=”” image_id=”225531″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225525″ title=”The Shadow of Death: Nine Inch Nails” index=”” image_id=”225526″]

***

Chuck Klosterman

Marc Spitz loved rock music, and he loved the people who wrote about it. He believed writing about music was the greatest job anyone could possibly have. He once tried to make a documentary about the history of music criticism, despite having never made a film before. The lack of experience did not concern him. “All you need is a great director of photography,” he insisted. Well, maybe. But even if that was true, who would want to watch a movie where a bunch of rock critics talk about themselves? “I don’t know,” he said. “Probably the same people who went to that documentary about the Helvetica font.”

Spitz never finished his movie, which–in retrospect–is slightly surprising. I have no idea how many pet projects Spitz failed to complete in his 47 years, but the number he finished is borderline remarkable. He wrote eight books over a span of 13 years, including a 426-page book about David Bowie, a 320-page book about Mick Jagger, and a 368-page book about himself. I’m unsure how many stories he published for Spin, but I doubt there are 10 people on earth who wrote more for that particular magazine. He somehow produced 13 plays, and playwriting was his goddamn hobby. Spitz drove a lot of people crazy, but he drove himself pretty hard. I can’t recall any conversation I ever had with him when he wasn’t working on a new book. He was mechanically prolific, almost as if he had no choice in the matter. He did not relax. He could not relax.

But (of course) for anyone who knew Spitz in any real-life context, the main thing they’ll remember is not his productivity. What they will remember is “The Marc Spitz Character,” simply because no one in the nonfictional world acted the way Marc Spitz acted, almost all the time. Wearing sunglasses and a scarf indoors was arguably the least weird thing he did. Spitz was not just the kind of guy who smoked in a non-smoking building; he was the kind of guy who’d spend 20 minutes searching for a posted sign that said you couldn’t smoke there, just so he could smoke underneath it. He would say obtuse things that were supposed to be self-evident, but the punch line was often unclear. Once, he wandered into the Spin offices and noticed a bunch of editors huddled in a conference room, listening to a promotional copy of a yet-to-be-released record. He asked what they were listening to. I told him it was a new album by The Roots. “Oh, The Roots,” he said. “Live rap. I get it.” I still have no clue what that implied. On many occasions, he would criticize whatever sweater I was wearing and tell me I needed to start wearing a suit whenever I was in public, because writers should always, always, always wear a suit. My typical response was that the upside to being a writer was that no one was supposed to care what you looked like. “You don’t get it,” he replied.

Spitz aspired to be Byronic. He believed life was better if people tried to be interesting, so he tried to be as interesting as possible. And sometimes that came across as absurd, but he obviously knew this. People thought he was self-serious, but he had a better sense of humor about himself than most of the people who made that criticism. Moreover, he displayed a much different persona when no one else was watching. He liked to talk about professional tennis. He liked to talk about dogs. He liked to talk about other writers and was highly complimentary toward any he viewed as remotely talented, a rare quality among music writers. But the thing (of course) he loved talking about most was the transformative power of rock, a metaphysical possibility he accepted unconditionally. He didn’t see someone like Morrissey as a normal human, even after he’d met and interviewed him. He was a true believer. Mythos was everything, for everybody (famous or otherwise). He was a “print the legend” type of person.

The last time I saw Spitz was at least three years ago. We were drinking, and I casually asked how many of his 13 plays had turned a profit. He said, “I think maybe one of them almost broke even,” a fact he found hilarious. He just enjoyed writing them. He was not in this for the money. He was in this for whatever “this” supposedly was, and he was committed.

Klosterman was a writer at Spin from 2002 to 2006. He is currently a writer and journalist living in Brooklyn.

***

Sarah Lewitinn

When trying to think about a memory from the past 20 years that best pays tribute to my mentor, Marc Spitz, I’m at a loss. I really want to remember him as the person I saw two weeks ago at the Library bar in the Lower East Side who had so much life, excitement, and humility in his eyes. I want to remember the Marc who spoke to me about his struggles with depression and how happy he was to be on the other side of it. I want to remember the Marc who hugged me as we cried together about all the times we should’ve been there for each other and how we wouldn’t let years go between our reunions, but maybe only days or weeks. I want to remember the Marc who was so optimistic about all the amazing projects he had on the horizon–from a musical he was working on to a young adult novel he was writing. I want to remember the Marc that was over the moon with excitement for Elizabeth Goodman’s book, Meet Me In The Bathroom, that she worked tirelessly on for years. I want to remember that Marc. That was the Marc I almost always saw–even when he made it really hard to see it–which he often did, at least until recently.

Right now my memories of our past are a blur of moments filled with laughter, fights, hugs, kisses, crying, and a feeling of closeness with a person that I would unsuccessfully seek to mimic for the next twenty years. There was a significant change in my life when I met Marc. For those who knew him, or even met him once, you know he’d typically make people feel like shit. Not me. He made me feel like a genius. He made me feel so cool and believed in me so much–something that wasn’t common in the years that preceded our introduction. I was so proud to be his friend. I was so proud he let me be his.

But this isn’t about me, this is about Marc, and if anything he’d rather I stay on topic (even though I know he was so proud of me and saw me as one of his achievements, as he should). And as I write this I can hear him taunting me, calling me by his nickname, Squirrel (a combination of Sarah and Ultragrrrl–he never called me Sarah). I can hear him in my head pretending to be a boogie man while giggling at the same time. He paces my mind like a goth bride, wearing an old band shirt, a new pair of … well, nothing. He’s borrowing my boa, and his soul is always blue. He wants me to talk about him and he’s not around to re-write my work, so I’ve gotta do my best. He knew my voice better than I did, so I feel really quiet right now.

Marc’s gift for writing was without question, but it was the warmness he wrapped his subjects in–and the inclusionary feeling he gave to his readers–that was unmatched. How confusing it must’ve been for those who read his pieces to meet him and be encountered by someone who could hardly look them in the eye, a trait of shyness he hid behind ludicrous sunglasses at all times. How confusing it might’ve been for those who held out their hands for him to shake only to have him walk in the other direction. How confusing Marc must’ve been until you had the balls to tell him you were going to accept him as he was–which would then grant you a hug, turn you into a therapist, and an ATM all at once–but how rewarding that could be. To have Marc shine his light on you was to be let into the greatest club of all.

His last text to me was “email it to me,” but the text before that was “Come Armageddon.”

Fucking Marc, man.

Lewitinn, aka Ultragrrrl, was a writer for Spin from 1998 to 2006. She is currently a music director living in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

***

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225550″ title=”These Things Take Time: Morrissey” index=”” image_id=”225551″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225787″ title=”Sharp Dressed Manskap: The Hives” index=”” image_id=”225789″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225538″ title=”The Fits and the Fury: The Vines” index=”” image_id=”225549″]

***

Carrie Thornton

I met Marc when he had just made his move from the “basement” of Spin.com to writing for the print magazine. I had just made a similar move—from the lowest rung on the publishing ladder, Editorial Assistant, to a new gig in a new house where I could actually acquire books of my own. I was thrilled beyond belief to stop making copies and working on books about potty-training and diabetes and to start acquiring the kinds of books I wanted to read. The first book I bought was Marc’s, one that started out as a biography of Darby Crash and ended up as an oral history of LA punk—We Got the Neutron Bomb. Marc and I grew up in our careers together—he got more cover stories, I published more high profile books. He got promoted, and so did I. Along the way I picked him up and helped build his confidence when his was in the toilet. He helped me relax, see the bright side when I was depressed, and even to remember how lucky I was to get to do something I loved.

As the years passed, I told him to take off his sunglasses at least a thousand times, and to cut the shit and just listen to me plenty of times, too. But I always knew Marc was, actually listening even though he didn’t want to give me the satisfaction. Our partnership flourished because it became a friendship. It was also a bonus that our musical tastes lined up pretty perfectly, and he often dropped little inside jokes about the post-punk and Brit pop we loved into his books that he knew would hit me just right–one of my favorites being the Depeche Mode cover band called the “Grobbing Honds” that appears in his second novel, Too Much Too Late. It was such a tiny detail, but so perfect and I laughed out loud when I came across it in the first draft of that book. This kind of close attention is what made Marc such a fun writer to edit and to read. It is those inside jokes we shared, built over nearly two decades of creative collaboration and true friendship, that best describe what I’ve lost. Marc and I just got each other.

Thornton is the Editorial Director of Dey Street Books, and edited Spitz’s We Got the Neutron Bomb, How Soon is Never?, Too Much Too Late, Bowie, and Twee. She is currently working on Loud Pictures, a book Spitz had recently finished.

***

Alan Light

I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who believed in rock & roll as much as Marc Spitz did. The grand gesture, the adolescent romanticism, the infinite possibilities of identity and sexuality–he bought it all, loved it, needed it. He was certain that rock stars were superheroes, and that for us journalists who were entrusted to pass along their musings to the masses, it was our obligation to get as close to their flame as possible—so there he was, doing lines with bands, making out with movie stars, sneering at requests from the DJ booth. When I took over as Spin‘s editor-in-chief in 1998, Marc was part of a motley group working on the just-born website, at a time when the web had no rules and no expectations. He was a snotty kid, using his dubious position as a way to get on the list for shows and parties. He was already becoming a star—somewhere (hopefully) there is still a collection of Polaroids of the Spin staff dressed up as Marc, resplendent in shades, boa, and dangling cigarette.

From the language in his scathingly honest, very funny memoir, Poseur, Marc thought I was a bit of a stiff (which, compared to him, I absolutely was). But he won me over with a dirty secret that he shared with most of the rock gods he idolized: He worked his ass off. Soon after I started at Spin, Axl Rose got arrested in a Phoenix airport, which suddenly added more urgency to the question of what the hell he’d been doing during years of isolation. Marc raised his hand for a news story, originally planned as a half-page, which he then began reporting relentlessly. Every day or two, he would swing by with word of new sources he had reached who had contact with Axl—Tommy Stinson, Moby—and we bumped the piece up to two pages, then to a full feature.

When he excitedly told me that he had spoken to Shaquille O’Neal, who had rapped in the studio with Axl, we knew we were onto something. My editors and I decided to make the Axl story a cover—on the condition that Marc get a quote from Slash (which, of course, he did.) Axl flipped out, calling me at home in the middle of the night when he heard our plans. With a glorious shot of a young Axl Rose (from a photographer who requested that we not give him a credit, for fear of antagonizing the subject) and the words “What the World Needs Now is Axl Rose,” the issue sold like crazy, and Marc had his first cover story. After that, there was no stopping him.

His limitless faith in the music seeped through every page of his biographies and novels, every second of the dozen plays he wrote, every line of his journalism. For years, he tried to talk me into working on a history of rock criticism with him; I was squirrelly about taking on something so self-referential, which I think was exactly what he liked about the idea.

I suppose I have to choose a last dance for Marc. He would hate that my first thought was “Don’t Stop Believing,” though he would appreciate the Sopranos reference since he was working on a book about rock and film at the time of his death. But let’s give the final word to his beloved Smiths. The spirit of Marc Spitz is a light that never goes out.

Alan Light was the Editor-in-Chief of Spin from 1998 to 2002. He is an author, journalist, and radio host.

***

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”226012″ title=”The Oral History of 2 Tone” index=”” image_id=”226014″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”226009″ title=”Mr. Show: The Oral History” index=”” image_id=”226010″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”226017″ title=”Jukebox Jury: David Cross and John Mayer” index=”” image_id=”226018″]

Andy Greenwald

I can still see him there, sitting in the long corridor that was Spin.com in the late ’90s: Sunglasses on, unlit cigarette dangling, back arched, arms extended over a keyboard like a goth mantis. Marc Spitz was intimidating then and God, he’s intimidating now. I can’t believe he’s gone. I kind of can’t believe he was ever here.

You have to understand that, for me, joining the staff of Spin magazine was a dream come true. But it also felt strangely easy. The assorted editors, writers, and art directors were mainly variations on a theme. Some wore glasses; others had English accents. But all had the same OCD CD shelves in their apartments. We made the same jokes about Pavement b-sides and C86 compilations. The majority of us danced about architecture more than we actually went dancing.

Marc was different and he was the first to remind you of it. He wore suits with skinny ties, feather boas, and a perpetual sneer. He prayed to rock gods; he sought out depravity and excess. At a time when many of us were playing with ironic agnosticism, he was militant and devout. When Marc saw Spin drifting away from its rebellious roots — Natalie Imbruglia? Heresy! — he stormed the stairs, stamped his boots, and got Axl Rose on the cover. When, a few years later, Creed’s Scott Stapp was plastered on that same cover, shirtless with a pious leer on his face, Marc made goddamn sure David Lee Roth in a banana hammock was front and center the very next month. This wasn’t a game to Marc. This was rock and roll. He took it seriously, even when it was wearing a banana hammock.

I’m pretty sure the first time I was introduced to Marc, as a wide-eyed intern in 1998, he ignored me. I know for a fact he ignored me for months after that. (Shyness is nice, as Morrissey once sang, but Marc wasn’t always.) Later, when I was promoted to a position that — for a very brief time, if you squinted — could maybe be construed as being his boss, I learned something else about Marc: He was secretly a sweetheart. The tie, the boa, the attitude: It was an act. He was playing a part, like Bowie, like Johansen, like McColluch, and all the other working class chameleons who, like Marc, used a combination of talent and chutzpah to will themselves into clever butterflies.

I owe him a lot. It’s because of Marc that I got my first agent — and subsequently wrote my first book. It’s because of Marc I went to my first burlesque show. (I think it was his birthday party?) It’s because of Marc that I lost my keys at an LES dive called Motor City. (A Spin holiday soiree; I think there was a dwarf dressed as Santa Claus?) It’s because of Marc that I know the best places to day drink and make poor nightime decisions in both the East and West Villages. (The Library and Radio Bar, respectively. Black and White was for when you were thirsty and stuck between the two.)

As the years went by, and Spin vanished from both of our lives, Marc appeared to me less like a vampire and more like a ghost. I would run into him on rainy afternoons, walking those dogs of his out on 11th Street, and we would make plans to get a whiskey or four but we’d rarely do it. He’d shake me by the shoulders and tell me about the book he was working on, the old records he was playing, the magazine that had let him down. And, inevitably, he’d tell me about his dream project: A documentary about rock criticism and how near (or far) he was to starting it.

Since I heard the impossible news about his passing, I’ve thought a lot about that project of his. I don’t write rock criticism anymore and I’ve developed a sort of self-protectively snarky shield around that fact. I joke about how grateful I am no longer to be speaking to drummers. I roll my eyes at breathless write-ups of derivative 20 year olds with borrowed style and brand-new guitars.

But this is bullshit and Marc would have been the first to call me on it. There is nothing honorable about faux modesty. He wanted to deify our bedraggled profession because he knew there was something noble there, something beautiful and searching. He knew he had to do it because all the other rock journos were too wifty and self-loathing to do it for themselves. (This is a man, remember, who adopted the role of “debauched character in a downtown memoir” as a twenty year-old and, when no one took him up on it, wrote the damn book himself.) Writing about rock music may not be the world’s most dignified calling, but it’s far from nothing. A good song can change your day; a good concert can change your night; a good album can change your life. And an electric write-up of any of those things can bring you, even if just for a moment, closer to it all. The truth is, every religion needs priests. And Marc was a fucking cardinal.

One last homily from the pulpit: I remember the vibe in the office 100 years ago, when The Strokes crashed into view and the way Marc talked about them. It wasn’t just that the songs were good (and they were really good) or that their hair was fantastic (and it was really fantastic). It’s that there finally was another New York City rock band, one unafraid of big choruses and hard drugs. A band worthy of the cover of Spin, worthy of adulation, worthy of the hangovers. A band that wanted to be great. To Marc, this mattered.

Marc Spitz believed there should always be a New York City band like The Strokes in 2001: funny, ambitious, fashionable, drunk. I don’t disagree but I’ll raise him one, just as I’ll raise my shot glass to his memory: There should always be a New York City writer like that too. He’ll be missed.

Andy Greenwald wore a variety of hats (Editorial Assistant, Director of New Media, Senior Contributing Writer) at Spin from 1999 to 2006. He is now a screenwriter and podcast host in Los Angeles.

***

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225520″ title=”The Rebirth of Cool: The Strokes” index=”” image_id=”225521″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225757″ title=”Don't Fear the Weezer” index=”” image_id=”225760″]

[featuredStoryItemBlock tile_id=”225524″ title=”Who The F**k Is Ryan Adams?” index=”” image_id=”225535″]

***

Victoria DeSilverio

We were on a morning train to Asbury Park, New Jersey. It was 1999, and we were on assignment for Spin, our first outside the office. Two Libras born a few days apart, we constantly tested our telepathy and regardless of the outcome, believed in it. On that train on the way to the beach with the sun shining, we were on furlough, “on the company dime,” as he liked to say, and everything was funny. Everything was ripe for a riff with Marc. Even when moody, bitchy or hungover, he’d still work the circuitry to deliver a nano truffle of absurdity, a gift that served us well on our assignments and during the rougher parts of our friendship. On the train Marc insisted on preparing, a habit I wish I had picked up from him, and we spent the time planning our attack on our mission–March Metal Madness, when wrestlers, death metal bands and porn stars formed an unholy alliance. Over one hundred bands were there, and we didn’t see one, so no Bloodfest, Anal Blast or Fallen Christ. Instead we roamed the halls, elbowing each other’s shyness away to approach the goths, with their dripping blood and spooky contacts, peer into their souls then steal them with photos.

After many false starts and giggles — Marc had a great giggle, which his Warholian hand gesture tried to contain — we managed to pry out of them (including the man who insisted we speak to him on the toilet, pants down) their thoughts on Third World debt, preparations for Y2K and where we go when we die. Marc was obsessed with death. Obsessed with aging. He often told me, with a mixture of disgust and glee that I would age, that my face would be wrinkled. He was obsessed with his legacy, that he not go without writing something great, which I think was a furnace for his ferocious productivity. Though deeply serious about his work, he was a very silly person, always in the act of word play and together we invented a vocabulary, a code language he’d remember like shock treatment and would over the years send like postcards from the past, instantly conjuring a feeling. For acquiescence or absolution.

One night on my stoop on Avenue C (still pre Y2K) we cooked up a plan to reunite the Smiths. We delved into the psych of each of the four and devised schemes we felt were fail-safe. We’d send Morrissey daffodils signed “Love, Johnny.” We’d go on Richard Blade’s radio show in Los Angeles (which we did and when it came time to read our on-air plea, our nerves made it sound like we were reading a ransom note). We’d talk to all four. Together we talked to all three, even meeting a cagey Mike Joyce in a darkened back booth at the Library bar on Avenue A, Marc’s second home, for hours feeding him drinks until we made him believe the reunion was his idea. And when we did, he grabbed me in excitement and threw his tongue down my throat; Marc then lunging across the table, grabbing the Smith by the shirt, saying, “hey, have some respect!” He carried many contradictions, Marc, and flew many red herrings. Peel away his studied femme persona, he was very much the son of a tough guy gambler from Long Island and he wasn’t afraid to throw a punch when needed.

It was his idea to scale the scaffolding to see Morrissey at the first Coachella. The security was scant in those days and anyway they were preoccupied with all the emotional cholos and cholas. We had our coveted VIP press passes, but we lingered with the Mexicans, immersed in their souped-up vintage cars, Moz tattoos and tears, kind of stunned our own obsession was clearly trumped and better dressed. Marc was someone I could indulge my love of science. We were anthropologists, allowing each other’s pathological need for watching and for feeling alien.

In the car driving back from the polo fields, we picked up a girl who had flung herself in front of our car, crying for our help. After a while driving, we understood synchronistically what was going down, and despite being very high, we trusted — we knew — the other was not being paranoid. A quick glance between us was all it took, and from the passenger seat, he reached back, opened the rear door and pushed her out before we met the hidden parked car she was leading us to. Adrenaline pumping, we drove back to the hotel and were gifted with a lobby filled with friendly talkative rockstars and a soft puppy to hold. Years later, after losing touch for many years, he wrote me, “We were psychic. Is psychic permanent?”

I adored his yearning for complicity. Marc seemed to live for the dastardly sweetness and promise of complicity, of being a part of a small gang. It was always us vs. them. And I think many of his friends had this same feeling with him. He had a way of bringing you into his fishbowl. And of course, a way of keeping you out.

Even when he turned like a mongrel cur, he had some queer loyalty to you, even if only, to the you of the past, which he seemed to cast in amber. Like he was devoted to being devoted, devoted to devotion itself. Devotion being like a religion to him, a source of both affirmation and pain. He was devoted to whatever ideal he imagined, and that went for friends and those whose talents he worshipped. He was devoted to the transcendence and power of music and writing, and he was devoted to some golden era from which he believed he was an heir. He knew he was good. He knew he was great. Some times, often times, he was such a dick about it and sometimes he was scared of his own talent, knowing it was something he was beholden to care for, to answer to. But he was a beautiful writer and an insightful writer and his vulnerability made him so, and his keen awareness of his faults made him a surgical observer of others.

I never read his books, even How Soon is Never, in which I’m the not so heavily disguised “Miki” character. It came out some time after he had told me he never wanted to see me again and I had taken him at his word. It irked him I didn’t read them, so much he insisted I had. But I didn’t care about them as I wanted to know about him from my own personal experience and not through his lens. I liked him more than he knew.

I had the privilege, shared by all his many friends, to be sent notes and these are my favorite pieces he authored. In the covert world of electronic mail, he showed his tenderness and his doubts and his attempts to divert perceptions, he was his simple self, someone who cherished closeness and was able to put it in words. “I thought I’d never see you again because I’m older now and I’m sure there are people I will never see again. I hope you’re not one of them though. I can see you without closing my eyes though so I guess what I mean to say is I wanna hang and have discussions with you.” This was the last time he wrote to me, a random note after a long time of silence, sent on a day I had a random fleeting thought of him. Maybe psychic is permanent.

DeSilverio wrote for Spin from 1997 to 2001. She is now a writer and producer living in Brooklyn.