On a chilly Monday afternoon last month, a group of record-collecting nerds of the highest order were listening to music and shooting the shit in the basement of Frank Dukes’s low-slung house in the sleepy Toronto suburbs. If you were to assemble a dream team whose skills include total recall of price histories for small-label Brazilian jazz first pressings and the ability to divine whether an album contains a drum break by its cover art alone, you’d be hard pressed to find a better starting five. There was Jacob Dutton, better known as Jake One, a producer who calls himself the “album cut assassin” and has credits on records by Drake, MF DOOM, and De La Soul. There was Gene Brown, a dealer who sells obscure vinyl for sampling to beatmakers like DJ Premier and Kanye West. There was Rana Chaterjee, host of a podcast for collectors and erstwhile host of a beloved and since-cancelled Toronto hip-hop radio show. There was a gawky guy in grandpa glasses who was introduced only as Chan Dogg—not a music industry player, but a “real heavy dude” in collector circles, I was later assured.

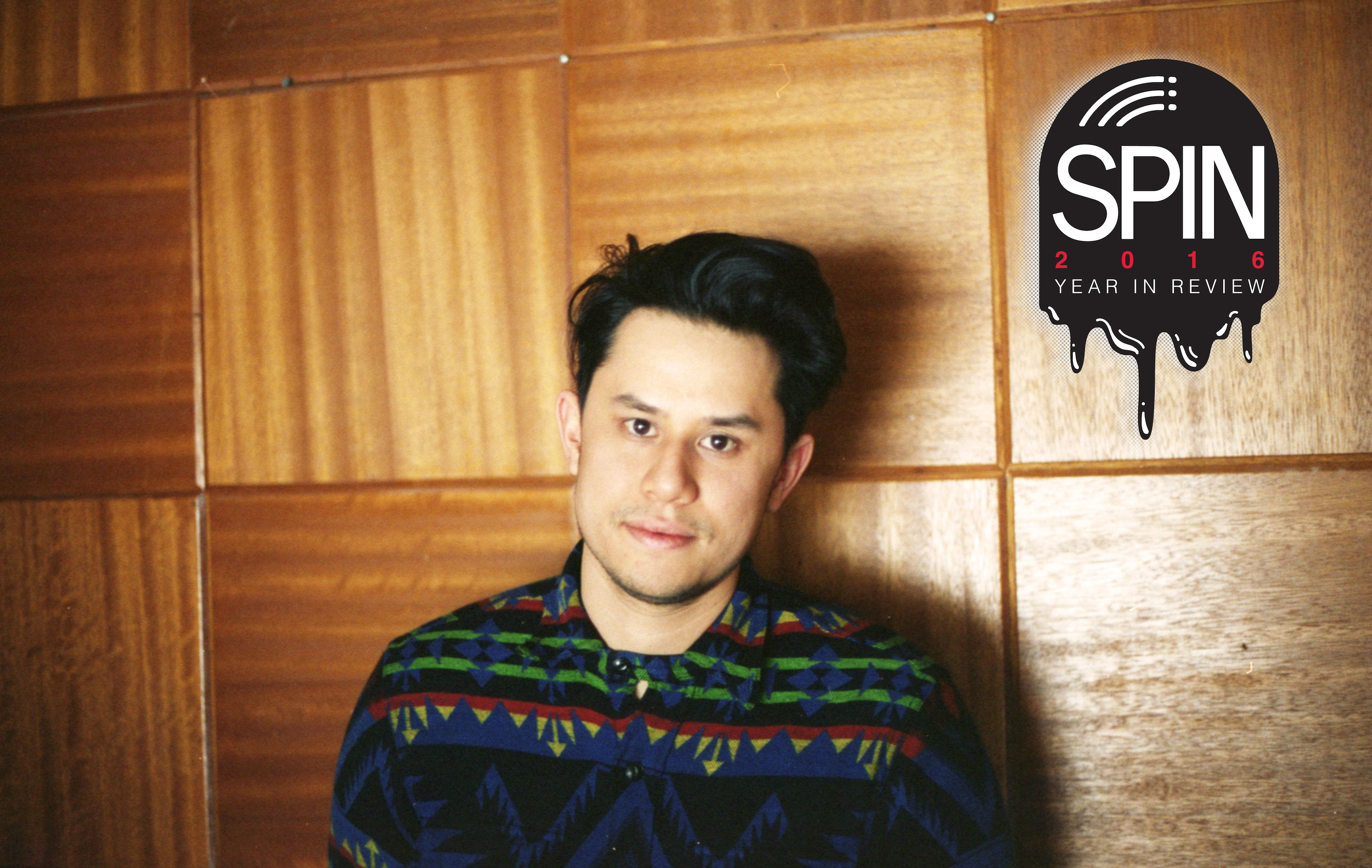

The host of the soiree has lately been the squad’s star player: Frank Dukes, Grammy-winning producer, who at 33 years old is slightly younger than the rest of the heads who were hanging out in his house. On hit records for Drake (“Fake Love,” “Right Hand,” and “No Tellin’,” to name a few), Kanye (“Real Friends”), Travis Scott and Young Thug (“Pick Up the Phone”), Rihanna (“Needed Me,” “Sex With Me”), Kendrick Lamar (“untitled 07”), and others, Dukes has honed a production style that is both a tribute to and a clean break from the sample-based methods of his friends and mentors.

Dukes began his career as a rap producer the old-fashioned way: By searching for funky old records, isolating the best bits, and placing them alongside booming drums. That approach has yielded great records, but it requires paying fees to whoever owns the rights to the original recordings and compositions, then waiting months or years for samples to clear before the song can be released. It sometimes means toiling to finish a beat, only to find that its samples can’t be cleared at all.

Early in his career, Dukes produced a few tracks in this way for artists like 50 Cent and Lloyd Banks. After completing the arduous sample-clearance process and seeing the modest returns he got for his work, he had an idea. He would record short loops of his own music and use them instead of samples to avoid the fees and delays. He would also license recordings out to other producers, who could pay Frank Dukes to use them in their own work. The program, called the Kingsway Music Library, was vertical integration for kick drums and bass lines.

Dukes receives production credits on songs for which he creates original music, but not on tracks that simply use Kingsway samples. This distinction can make his catalog difficult to track. A single, jazzy piece of music he created for Kingsway, titled “Vibez,” was sampled in Drake’s “0 to 100 / The Catch Up,” Logic’s “Top Ten,” Tinashe’s “On a Wave,” Yuna’s “Broke Her,” and Curren$y’s “Game Tapes,” all by different producers. “I was sampled on the Selena Gomez record, some random-ass bonus song on her last album,” he said. “I just got sampled on Kevin Hart’s album. It’s pretty weird, random stuff across the board.”

https://youtube.com/watch?v=9_Rm2TEf-9k

Dukes and his friends were congregated in his basement after a record fair that Chaterjee hosted. Gene Brown had traveled from North Carolina to peddle his wares, and he was hoping to offload a few more records to his buddies before the long drive home. Dukes, mellow and affable in a Supreme rugby shirt and army-green beanie, declined to purchase most of what was on offer, but he had kind words for Brown’s selections. A record whose chintzy 1970s sleeve bore only the title Waves was “just the right amount of cheesy,” he said, in a Canadian drawl that sounds almost Texan to American ears. “The music makes me feel like I should be wearing white pants,” he added, evoking the breezy opulence of yacht rock and ‘90s R&B.

Then, Brown played Miniatures, a compilation released in 1980 which assembled 51 minute-long song sketches by art rockers like Robert Wyatt and XTC and was curated by the keyboardist from Mott the Hoople. The room nearly broke into applause upon hearing a lurching, amateurish cover of “Cum on Feel the Noize,” recorded by the British comedian Neil Innes, with his preteen son singing and working hard to keep time on the drums. “That’s crazy!” someone–maybe Chan Dog–shouted. The late, great, J Dilla had once used the “Noize” version from Miniatures in one of his songs, completing a heroic feat of crate-digging by finding a worthy sample on such a bizarre slab of vinyl. Dukes bought the album for $40.

Next up, Brown put on some Israeli-sounding music that triggered a memory from Jake One. About a decade ago, he’d sampled an Israeli song without clearing it for Boom Bap Project, a relatively little-known Seattle rap group. The rightsholders came looking for a check, and Jake told them to take whatever percentage they wanted—Boom Bap Project’s album hadn’t sold well enough for the finances to matter. Still, he’d sworn off sampling Israeli music since then, just in case. “That was the first time I got got on something that I didn’t know I’d get got on,” he said. In other words, he thought he’d be able to sample from an obscure international source without paying up, and he was wrong.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”220020″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2016/12/DL_161412_FrankDukes_Film_10-1481813908-300×192.jpg”]

Ever since a handful of Caribbean teenagers in the Bronx jury-rigged a catalog of dancefloor heaters with drum breaks and horn stabs cobbled together from likes of James Brown and the Incredible Bongo Band, sampling has been a central component of hip-hop music. Early producers embraced cut-and-paste composition partially out of necessity. It was easier and cheaper to buy an MPC and some dollar-bin records than it was to acquire a full suite of instruments and recording equipment. This workaround imparted hip-hop with the ability to transcend time and style, a kind of postmodern technological magic. Some kid in 1989 with a Walkman shoved in his back pocket heard De La Soul’s “Eye Know” for the first time and lost himself in a reverie worthy of Proust: It was a jaunty rap song with an eager white guy singing the hook; it came from a grown-up world of nightclub marquees and foreign films, with its lush horn charts and guitar chords lifted from Steely Dan; it was a dusty old album he’d heard once or twice, through the walls of his nerdy older brother’s bedroom, refashioned into something new.

Classic albums like De La Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising and the Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique were crafted almost entirely from samples, offering listeners a panoply of sounds and associations unlike anything recorded before them. (In addition to Steely Dan, De La sampled Otis Redding, Sly & The Family Stone, Lee Dorsey, and The Mad Lads on “Eye Know” alone.) At that point, disputes over copyright and payment to the sampled artists were handled out of court, if they were handled at all, and the limited attention paid to sampling meant producers and DJs could assemble vivid collages of sound without worrying about costs. “Twenty-five years ago, we were told that hip-hop and rap was a phase, that this music wasn’t going to be around,” said Deborah Mannis-Gardner, a sample-clearance expert who founded her own firm in 1996, and whose clients include J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar. “How rude was that comment? But a James Brown sample, we could get for a $500 buyout. It was a whole different mentality back then.”

Things changed quickly. In an out-of-court settlement in 1991, De La paid members of The Turtles $1.7 million for sampling their song “You Showed Me” in the 3 Feet High interlude “Transmission From Mars.” That same year, Biz Markie was found guilty of copyright infringement and ordered to shell out $250,000 in damages over a Gilbert O’Sullivan sample. The Wild West era of sampling was over. Still, for artists who were willing to go through legal channels, sampling remained affordable for a while. “I still made music the same way after that. I went through all the protocol that I always do to clear my samples, it’s just that my record company dropped the ball,” Markie told SPIN by phone. “It depends on who has the publishing, and who has the rights. A lot of people are cool with it, and some people ain’t. Some people got sentimental reasons why they don’t want to hear their music coming out on a record.”

Over the next decade, as hip-hop grew more and more popular, record labels and publishers identified sample clearance as a lucrative revenue source, and they began charging artists more money for rights. Today, clearing the same James Brown sample that Mannis-Gardner got for $500 in the early ‘90s would be many times more expensive. Sampling a simple drum beat, for instance, might require giving 7.5 to 10 percent of songwriting royalties to whoever owns the publishing for the original song—the rights to the melody and the words. An additional percentage of record sales is owed to whichever label owns the rights to the original recording. One side effect of this dual payout is the increased use of “interpolation,” a painstaking process by which producers re-record a sample with their own instruments, to sound as much like the original as possible. Songs that use interpolated samples require artists to pay for publishing rights but not for the original recordings, and the additional cost of recording a new version is offset by money saved on royalties down the road.

Sampling is no longer an inexpensive way to make music, but gone too are the days of producers needing to buy instruments and hire a band. Software like Ableton or FL Studio costs a few hundred dollars and allows producers to make music on their laptops using synthesizers and drum machines, with no samples to clear. Accordingly, the prevailing sound of rap has shifted from drum breaks and dusty loops to crystalline keyboards and skittering digital percussion.

Old-school sampling is on the wane, music copyright infringement lawsuits seem more common than ever, and pop hits are increasingly assembled by committees of songwriters and producers who send digital files back and forth across the globe. Against this backdrop, Frank Dukes, with his library of homemade samples, seems like the ideal producer for our era. If you don’t recognize his name, that’s because his songs are nearly always assembled piecemeal, with Dukes’s music set against drums and arrangements from another, generally more famous producer, who gets top billing (On Rhianna’s “Needed Me,” for instance, he worked with DJ Mustard, whose signature “Mustard on the beat, hoe,” is the only tag that adorns the track.) He is one of six songwriters credited on “Attention,” a track on The Weeknd’s Starboy. Jordan Sargent summed up the state of affairs in SPIN’s review, writing that Starboy contains “two handfuls of the finest pop songs that the great, whirring Song Machine has to offer in 2016.”

With his free-floating fragments of music, Dukes might be thought of as just another cog in the song machine. But his two-pronged approach to disseminating his work and his method of creating “samples” from scratch differentiate him from his industry peers. Dukes’s work with The Weeknd falls into the original production side of his oeuvre: The music he created on Starboy is exclusive to the album, and he guided how his music was used. His Kingsway Music Library material, on the other hand, is available to anyone to do whatever they want with, from the lowliest Soundcloud producer all the way up to Kanye or Mike Will. Kingsway offers about a dozen collections of music, with names like Baked Goods and Lap of Luxury, purchasable for $40-$80 each. Once producers have downloaded a collection, they’re free to use and manipulate the music inside however they see fit.

Kingsway also charges a percentage of royalties to clear samples, just like a record label or songwriter would. Dukes generally splits the publishing 50/50 with the producer of a song that samples his music, and Kingsway offers free clearance of the master recordings for self-released projects, but takes a percentage for those released on major or independent labels. In general, Dukes said, clearing samples with Kingsway is significantly more affordable than sampling from albums, and it’s also less of a hassle. “I know people who have sampled gospel music, and then they go to clear the sample, and it’s like, ‘You can’t take the Lord’s music and make this,’” he said. Sample clearance is Kingsway’s entire business model, and accordingly, Dukes is agnostic about who is doing the sampling.

He attributes his willingness to let music into the wild in part to the frustration he felt when he couldn’t clear samples for his own songs. It also helps that the musical ideas that he slots into the Kingsway collection are generally those that he hasn’t found a use for in his own production work. “I don’t really generate material specifically for the Kingsway Music Library,” he said. “It’s just a product of the way I work. I make so many ideas, it’s impossible to finish every single one. If I have ideas that are really precious to me, that I’m working on and turning into songs, I’ll end up producing those songs myself. Once I put it out on Kingsway, I look it at as being no different from somebody picking up an album and sampling. It’s up to their interpretation.” Sometimes, that laissez-faire approach yields great records from producers who hear something that Dukes might have missed, like “0-100 / The Catch Up,” or Future and Drake’s “Diamonds Dancing,” another song based on a Kingsway sample. Sometimes, it means Dukes’s music ends up on a Kevin Hart album.

One might expect that collaborating on such a broad scale would dull an individual contributor’s voice, but Dukes’s aesthetic is easy to hear. Informed by the shimmer and yearning of Phil Spector and the luxurious hollows of fellow Toronto beatmaker Noah “40” Shebib, Dukes’s music feels wet and distant, like a rainy cityscape at night, glimpsed from inside a car with a booming stereo. He enjoys experimenting with genre. The lilting rhythms of “Pick Up The Phone,” he said, were inspired by “tons of Samba and Brazilian music–really breezy, airy shit.”

Dukes’s sample simulacra are filled with nostalgia for a nonspecific place and era in pop history, where some long-forgotten ensemble is playing smooth funk in the corner of a penthouse bachelor pad and Ray J and Frank Sinatra are at the bar chasing their cocktails with heavier inebriants. Dukes created his style partially in response to market preferences, but like the cash-strapped New Yorkers with samplers who invented the sound of early ‘90s hip-hop, he has managed to wring something original from his gambit.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”220024″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2016/12/DL_161412_FrankDukes_Film_9-1481814104-300×189.jpg”]

Dukes’s real name is Adam King Feeney; he took his moniker after Frank Dux, Jean-Claude Van Damme’s character in Bloodsport and the real-life martial arts master who inspired the film. Though he spends about a week each month traveling to far-flung studios for work, he keeps normal hours when he’s in Toronto, he says, spending time with his wife and two young children. He’s friendly and self-effacing, joking that he picked up much of what he knows about composing from sharing a studio with the rap-inflected jazz quartet BADBADNOTGOOD.

The Feeney family residence sits on a not-quite cul de sac, just off a large tranche of parkland and golf courses; to get there, you drive down a four-lane arterial road, passing a pre-school and a shop advertising quartz and granite countertops. In the basement, there are vintage keyboards piled up and ASCAP awards for his contributions to “0 to 100 / The Catch-Up” and Jeremih’s “Planes.” Instead of a coffee table, there is a child’s train set, complete with a thicket of Thomas the Tank Engine models. It’s the sort of home where you’re asked to take your shoes off upon entering, and when you’re offered a drink, it’s not liquor or beer or even coffee, but a ceramic mug filled with filtered water.

Despite the nocturnal nature of his music, Dukes began a recording session last month well before sunset. He was huddled in his home studio with Kaan Gunesberk, a Toronto-based indie songwriter and multi-instrumentalist with a malleable voice and playing style. “When you’re producing, you’re really just making a series of decisions,” Dukes said. Those decisions could be as simple as where to place the microphone on a snare drum, or, as in the work of Phil Spector, they can be as involved as handpicking the members of a rock’n’roll orchestra. The right drum sound can make a merely great record into a transcendent one—ask Spector about that—but the tedium of all those decisions can also stifle creativity. The object of the session with Gunesberk was to record a musical stream of consciousness, capturing their unvarnished sonic instincts to generate as much material as possible in a limited timeframe. Dukes would figure out how to use what they came up with later.

Dukes put on a progressive rock record he’d bought from Gene Brown, moving the needle seemingly at random, until a brief arpeggiated figure from a wanky synthesizer solo caught his ear. Frantic in tempo and gushing with the polyester enthusiasm of the keyboardist who played it decades ago, the music had none of the chilly allure of Dukes’s work. “That melody, but as voices, could be really cool,” he said, singing along to the solo in a shaky falsetto until Gunesberk joined in. “Do you want to fuck with that?”

Gunesberk approached the microphone and started singing, adding melodic flourishes that weren’t present in the original. Dukes played chords on his keyboard that were filled with murky jazz voicings, without concern for the harmonies the prog rock band was using. He instructed Gunesberk to match the chords with his voice, adding layers of barbershop harmony. They worked with dizzying efficacy and enviable calm, racing away from their kitschy source material at full speed.

“You know how, on a Jodeci record, people are always playing some crazy, busy synth line?” Dukes asked, and sang a spot-on imitation of some sexed-up new jack swing keyboard sounds. Gunesberk reached for a tiny toy Casio that had probably been purchased at a yard sale, ignoring the studio’s several pricey and powerful synthesizers. As Gunesberk played, Dukes leaned forward, grinned, and gave direction: “You got to do the mad twiddle. You’re a session player, with a ponytail, wearing some white pants right now. Shit yeah. Now do the first one again, but with no twiddle.” Even Dukes’s studio banter has a postmodern aspect. He was urging his partner to imagine himself surfing through the pop music canon, a session player with a ponytail—despite the fact that Gunesberk really is a session player who works on huge pop records, and he really does wear his half-bleached hair in something like a ponytail. (His pants, regrettably, were not white, but a dark corduroy.)

Gunesberk finished playing, and Dukes fiddled with the audio effects, pitching Gunesberk’s voice up an octave and filling it out with lush reverb. Suddenly, it sounded like a Frank Dukes production. The effects gave Gunesberk’s voice an ethereal quality and the new chords imparted the melody with slow majesty. In less than an hour, what began as a forgettable lick in an unremarkable synth solo became an icy monolith. The drums weren’t yet in place, and they’d likely be added by another producer, either one of Dukes’s collaborators or his Kingsway clients, depending on whether he decided to use the idea himself or put it in the library. Still, it was easy to imagine the finished version. “It sounds like an outro,” Dukes said to himself, and moved on.

He outlined another idea. Inspired by his 3-year-old son’s musical iPad games, Dukes wanted to record dozens of short instrumental loops, all in the same key and tempo, but otherwise unrelated. In theory, these loops could be layered in any arrangement and still make rhythmic and harmonic sense, yielding a nearly endless stream of combinations that could be slotted into songs. “When my son wanders into the studio and asks what I’m doing, I always tell him, ‘I’m working,’” he said with a laugh. “Now, when he’s playing with these iPad games, he’s like, ‘I’m working, dad.’”

Dukes and Gunesberk set about recording loops, using keyboards, toy percussion, a wine bottle, a squeaky reclining chair–anything and anyone within arm’s reach. Gunesberk, whose voice adorns Dukes productions like Drake’s “Right Hand” and Post Malone’s “Deja Vu,” did improvised impressions of Sade, Ray J, Janet Jackson, and Thom Yorke, singing gibberish prevocal sounds instead of words.

Then Dukes turned to me. “You know a little music theory, right?” he asked. “Want to put something down?” A little taken aback, I approached the keyboard and played the first thing that came to mind, a plodding, ominous figure with a descending bass line, in G minor. Dukes fired off some friendly but firm directions. He liked the first part, but the ending needed to be more hopeful, so could I try it again with an E-flat subbed in for the third chord? I stumbled around a bit, then Gunesberk stepped in and recorded a more polished version of my idea, incorporating Dukes’s compositional tweaks. “I like having him around because he can finish my musical sentences,” Dukes said.

I took my leave as the duo was workshopping an idea that arose from the layering game, pairing slowly unfolding synth arpeggios with Gunesberk’s processed voice to create something that sounded like a lost collaboration between Destiny’s Child and Tangerine Dream. “That could end up on a Drake record,” Dukes said as I gathered my things. “Or it could end up as nothing.”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”220026″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2016/12/DL_161412_FrankDukes_Film_7-1481814203-300×184.jpg”]

The following evening, Dukes broke his normal person hours to attending a late-night recording session for Safe, a babyfaced 20-year-old Toronto rapper whose debut album Dukes is executive producing. Safe owes his success in part to Drake, whose cosign led to a deal with Epic Records. He was working in a sparsely appointed studio in the suburb of Etobicoke, surrounded by fellow members of Halal Gang, a loosely affiliated crew who mostly hail from Toronto’s Somali population. They cracked jokes about girls and the new Harry Potter movie, eating pizza and drinking Pepsi that was occasionally spiked with Hennessy. Dukes came armed with two beats that evidently began as jam sessions like the one from the previous night; each featured a snippet of Gunesberk’s high, affectless singing. He played the first, which pitted a loping steel pan melody against massive slabs of bass. It sounded like a harder, less poppy version of Dukes’s work on “Pick Up The Phone.” The young men nodded furiously. “That was sick,” Safe said, punching lyric ideas into his phone.

Dukes has taken a mentorship role with Halal Gang, and until about 2:30 a.m. he offered melodic and lyrical guidance for their songs-in-progress. He rapped some lines to Safe that incorporated a bit of Toronto slang. “I feel like you’ve gotta do something that’s just what you guys be saying,” he said. “It might catch on.” Safe raced into the vocal booth and began playing with the idea: “Heavy with the wrist motion, working all week / Young nigga, feel like an OG!”

Dukes and the rest of the gang watched Safe from the control room, rapping over the steel pan beat, lyrics scrawled on graph paper. Though Safe was in the next room, you couldn’t hear his natural voice, only the version that had been picked up by the microphone, transmitted as electricity through a cable embedded in the walls, converted to a digital stream of ones and zeroes, received by a computer running Pro Tools, analyzed and processed by Autotune, and converted back into electricity–the otherworldly sound that was blasting from the studio speakers along to the beat, in perfect time with the movements of Safe’s mouth. The scene, with its layers of invisible technological mediation, would be incredible if it weren’t so commonplace.

As I watched and listened, I thought about the painter Chuck Close, who creates portraits in eerie, photorealistic detail, based on images captured with a specialized camera. Photo portraiture began as a cheap and accessible alternative to painting, just as sampling began as an alternative to recording original music. By painting photographs and recording original samples, Close and Dukes create facsimiles of facsimiles. Their works are so abstracted from an original idea that they have become original again. Just like those hypnotic drum breaks that Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash crafted with two turntables and a mixer on sweaty Bronx dancefloors in the 1970s, they work on an eternal loop.