This week, documents obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union revealed that the Baltimore County Police Department used specialized software to monitor the social media feeds of activists and others during the unrest that followed the killing of Freddie Gray in 2015. Looking back at the way that unrest unfolded, it’s easy to see how surveillance of this kind may have helped escalate a day that began with peaceful protests escalate until the riots that briefly lit up the city.

The ACLU of California conducted an investigation into law enforcement use of products developed by Geofeedia, a Chicago-based company that touts its ability to quickly collect and analyze large huge batches of public social media posts, helping clients “predict, analyze, and act based on real-time social media signals.” Among the documents they turned up was a “case study” that Geofeedia sent to the police department in Glendale, California, detailing the ways in which the Baltimore County Police Department used Geofeedia’s services during the Freddie Gray protests. (Multiple agencies including the Baltimore County PD, which patrols the area immediately to the city’s north, assisted the Baltimore Police Department’s response to the unrest.) Geofeedia responded to the ensuing controversy with a statement on its website, pointing out that its service only provides access to publicly available social media posts, and that its clients also include private companies and non-law-enforcement government agencies.

According to the case study obtained by the ACLU, Geofeedia alerted a Baltimore County police official named Steve Vaccaro to “increased chatter from a local high school about kids who planned to walk out of class and use mass transit to head to the Mondawmin Mall protest.” “We were able to turn around and alert the local police, who intercepted the kids–some of whom had already hijacked a Metro bus–and found their backpacks full of rocks, bottles, and fence posts,” Vaccaro is quoted as saying.

The Mondawmin Mall protest that Geofeedia’s case study is describing was a pivotal juncture on April 27, 2015. On that day, the temper of West Baltimore crescendoed from grief in the morning, at Gray’s funeral, to rage in the evening, when rioters burned police cruisers and a CVS. As the Baltimore Sun notes, a bus station at the Mondawmin Mall is a transit hub for students coming to and from school. That afternoon, the city shut down service at the Mondawmin station and police flooded it with riot cops before students were out of school. It was there that violent clashes between protesters and police began in earnest, before concentrating at the intersection of Pennsylvania and North avenues, about a 20 minute walk away.

Also Read

Pride Crowds

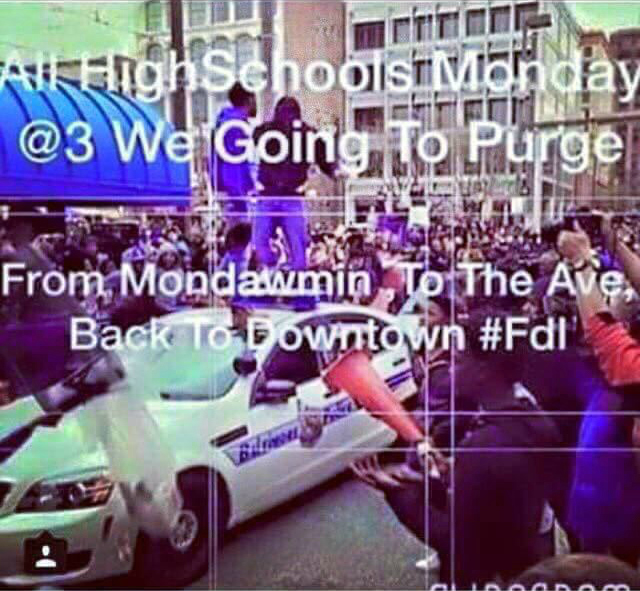

The officers congregated at Mondawin in part because of a meme that had circulated on Instagram calling for a “purge” after school that day–a reference to the 2013 movie about a day during which all crimes are temporarily made legal. The idea that a group of children would spontaneously enact total lawlessness at a given time, or would even be capable of doing so, is plainly ridiculous. The “purge” meme was much closer to an ordinary schoolyard boast, and a channel for grieving teenagers to express their frustration with those they are told to trust, than it was to a criminal conspiracy.

It cannot be asserted that officers became aware of the “purge” via Geofeedia surveillance, but the company’s mention of the “Mondawmin Mall protest” suggests that it is exactly the sort of thing that Geofeedia would pick up on and funnel to officers in the future.

Maybe some of the students whom the cops intercepted were the troublemakers armed with rocks and bottles that Vaccaro describes in his quote, but most of them were ordinary kids, just trying to get home from school. Conservative media coverage of the afternoon focused on teens who threw projectiles at officers, but multiple officers were documented throwing rocks into crowds of teenagers as well. A Baltimore city schoolteacher named Meg Gibson described the dynamic at Mondawmin in Facebook posts that were republished on Gawker the following day:

“The riot police were already at the bus stop on the other side of the mall, turning buses that transport the students away, not allowing students to board. They were waiting for the kids,” a Gibson wrote. “As I sat at the intersection of Gwynns Falls, I saw several police cars arriving at the scene. I saw the armored police vehicle arrive. Those kids were set up, they were treated like criminals before the first brick was thrown.”

The Baltimore County Police Department began a five-year contract with Geofeedia last year, for which it will pay the company $20,000 per year for its “location-based social media monitoring” services, a document obtained by SPIN via a Maryland Public Information Act request shows. The department does not yet have formal doctrine governing use of the service, BCoPD Cpl. Shawn Vinson told SPIN, but is “in the process of writing procedures” for its use. Documents similarly obtained by the Baltimore Sun show that the Baltimore City Police Department and the departments in several surrounding counties also have Geofeedia contracts.

In a letter sent to social media companies in the wake of its investigation, the ACLU wrote that Geofeedia data “enables dangerous police surveillance…chills free speech, and threatens democratic rights.” And the effects of this sort of surveillance aren’t limited to abstract ideas about liberty. The events of April 27th might have looked very different if police hadn’t flooded Mondawmin after news of the “purge.” And without social media surveillance–either via Geofeedia or more primitive methods–the purge meme probably wouldn’t have landed on their radar at all. In the days following ACLU’s report on Geofeedia, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram all suspended the company’s access to their data. After considering what happened in Baltimore, it’s easy to understand why.