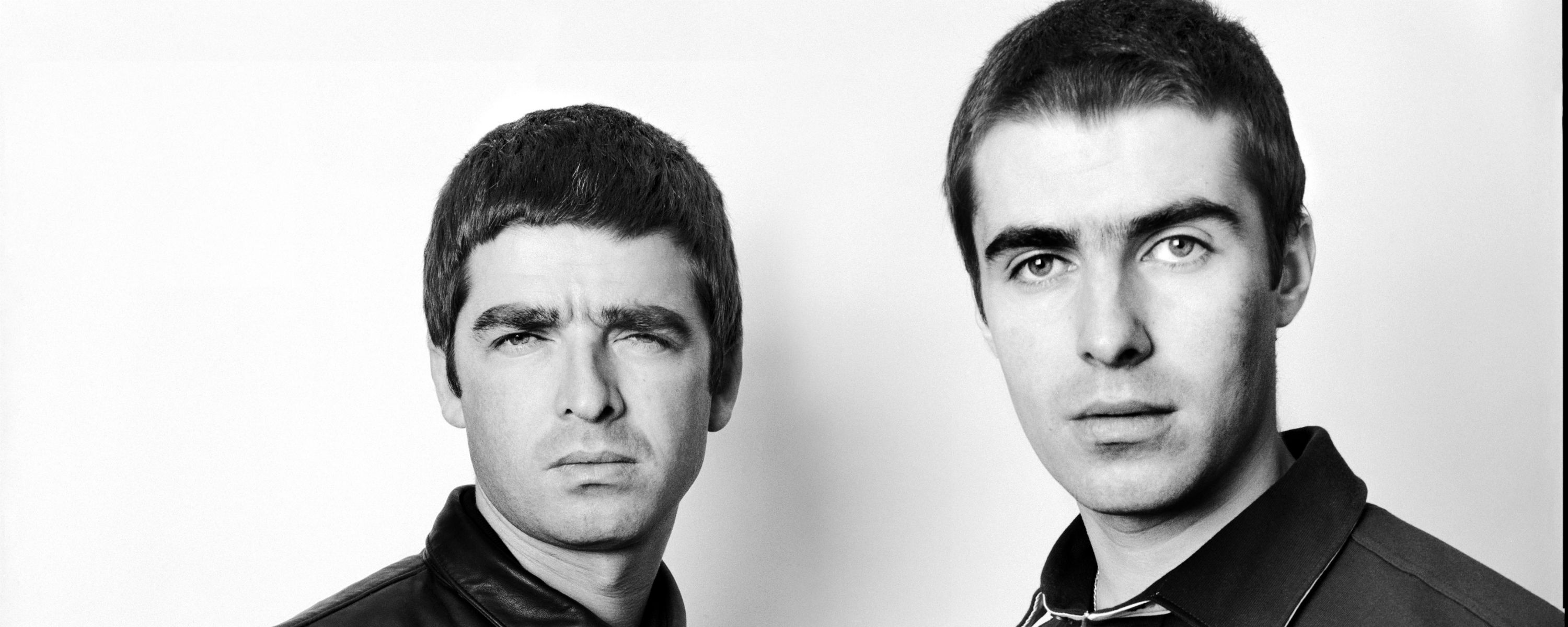

I used to be the worst kind of Oasis fan—every bit as brash, self-satisfied, dismissive, and deluded as the Gallagher brothers themselves. Hell, I even took pleasure in insisting to people that they were chumps for writing the lads off, absurd as that idea was in 2003, when I first fell for the Manchester band. By then, there was no denying that Noel Gallagher’s powers as a songwriter had dulled following Oasis’s canonical first two albums, just like there was no denying that Americans’ interest had largely disintegrated in tandem.

But I simply didn’t care; I was so far gone that I was happy to cosign lesser imitations of past triumphs. But unique as my insistent loyalty might’ve felt, I was still drawn to the same strengths that won them millions of fans in the ‘90s: Noel’s proudly British lyrics; choruses that could make your throat clench and your heart threaten to burst; Liam’s sneering vocals and pissed-off posture; the cocktail of ego, camaraderie, and one-upmanship that made Oasis as entertaining and volatile offstage as on.

Not coincidentally, all of these elements are also at the center of Oasis: Supersonic, a new documentary that lovingly charts the group’s glory years. Directed by Mat Whitecross and executive produced by Asif Kapadia (the director behind last year’s Oscar-winning Amy Winehouse doc, Amy), Supersonic marvels at how a five-piece led by two brothers from public housing—two “headcases,” as Noel puts it in the film—became the defining musical act for a generation. That honorific does come with an asterisk: Oasis were the defining musical act for a U.K. generation. As popular as their blockbuster sophomore album, 1995’s (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, was in the U.S., the Mancs never matched their home-country ubiquity here in the States. (Still, stateside interest in Supersonic is strong enough that the doc’s limited U.S. theatrical run—originally planned to be just one night only—has been extended for a week in a few markets, including New York and Los Angeles; the film is also currently available On Demand and through iTunes.)

From a purely American perspective, it can be a bit disorienting to see just how massive Oasis were across the Atlantic. The movie opens as the group descends upon England’s Knebworth House festival grounds during the summer of ‘96, just before their crowning achievement as a live act: a two-night stand in front of a total of 250,000 fans. Legend has it that they were the most in-demand tickets in Britain’s history, with one in 20 Brits applying for passes, according to the BBC. Twenty years later, pretty much every member of Oasis at the time acknowledges this as their pinnacle, and admits they probably should’ve packed it in afterward. Noel in particular recalls feeling like the history-making gigs were the beginning of the end, that they couldn’t possibly get any bigger—and this was just three years after they’d signed with the U.K.’s Creation Records.

Whitecross spends the documentary building to those shows, starting from the Gallaghers’ troubled childhood, which was blighted by an abusive father that they eventually abandoned. “In some way,” Noel says at one point, “my father beat the talent into me.” After working as a roadie for Manchester outfit Inspiral Carpets, Noel joined the band that his baby brother Liam was fronting with some mates: guitarist Paul “Bonehead” Arthurs, bassist Paul “Guigsy” McGuigan, and drummer Tony McCarroll. Soon enough, the older Gallagher began writing songs about friendship and immortality, being underemployed and overconfident, the allures of rock stardom and snorting Alka-Seltzer. Thanks to outsized stage magnetism and playing the right club at the right time, they landed a record contract. “We weren’t the best musicians, but we had the spirit,” Liam tells the filmmakers, accounting for what set Oasis apart.

All of this is related with a mix of archival footage and some animation—Whitecross doesn’t bother with talking-head segments anywhere in the film, instead laying interviews over footage as narration. It’s an engaging tactic: Pairing audio of Noel acting out a story from the band’s early days with video of what appears to be the exact anecdote he’s describing creates the sensation of actually being inside of a memory. And the director isn’t wanting for memories. He’s got all of the principals on record—the original bandmembers; Noel and Liam’s mom, Peggy Gallagher; Creation co-founder Alan McGee; Oasis sound engineer and honorary sixth man Mark Coyle—and their recollections have been neatly edited to unpack and explore the various facets of Oasis’s story.

The Gallagher brothers themselves—always entertaining interviews—are articulate and speak with self-awareness, reminding you how sneakily sharp they can be, despite regularly behaving like parodies of themselves in public. It really is a small miracle that Liam and Noel—now 44 and 49, respectively—both agreed to be involved with this project, coming aboard to executive produce and be questioned separately. Even more amazing is how warm they are when discussing the band they both anchored for nearly two decades. They each attempt to describe their dynamic—Noel says it’s as simple as the differences between a cat and a dog—but there’s virtually none of the pettiness and ugliness that’s hung over the brothers since Oasis imploded in 2009. No one’s torn down or compared to a potato, and their still-ongoing feud is merely alluded to, never addressed directly. (Of course, when Liam saw the film, he apparently couldn’t help but throw popcorn at the screen every time Noel appeared.)

Supersonic is an essential companion piece to Definitely Maybe and Morning Glory.

Because Supersonic cuts out at Knebworth, we don’t see what happened once Oasis were undone by their own success. They followed their hall-of-fame run with 1997’s Be Here Now, their notoriously overblown and indulgent third album, a record that’s become a monument to the moment when an act loses the plot and gets way too high on what they’ve been peddling (along with mind-numbing mountains of cocaine). What started as salvation became a business; inspiration quieted, sales started to dip, lineups changed, and Oasis faded from relevance. Choosing not to bring all this up makes the film feel a little like a eulogy—Whitecross prefers to not discuss the least-flattering splotches on the band’s life story.

That might make you wanna scream “puff piece” or label Supersonic as nothing more than a two-hour compliment, but the foundation is certainly laid for the conflict and dysfunction that eventually sunk Oasis. Besides, I’m not exactly dying for the scuttlebutt on their stillborn reboot, 2002’s Heathen Chemistry. Whitecross presumes that if you’re interested enough to seek out a full-length documentary about a rock band that hit its zenith when Hillary Clinton was still First Lady, you likely know what happened after the champagne supernova dissipated. He’s more interested in how the story began, and why it mattered.

If you’re curious about the Gallaghers’ less-heralded days, the records are there. Be Here Now was even reissued recently—the nearly 72-minute slog has been padded out for a triple-disc edition that exceeds three and a half hours, repackaging some B-sides, a handful of live performances (including one recorded at Knebworth), and a slew of demos mostly made on the Caribbean island of Mustique in ‘96. That’s a stunning expansion of a record Noel once described as “the sound of a bunch of guys, on coke, in the studio, not giving a fuck. There’s no bass to it at all; I don’t know what happened to that.” Supersonic skipping over this chapter makes for an especially disappointing blind spot; it would’ve been fascinating to see the band’s peak decadence treated with the same detail and focus that’s given to their rise. Narratively, though, it’s understandable that Whitecross wouldn’t delve into Be Here Now—it would corner his film into ending on a down note, and set the Knebworth framing device off balance.

Back when my near-obsession was at its most intense, I’d stump for Be Here Now as a worthy successor to the first two LPs—Morning Glory and its working-class predecessor, 1994’s Definitely Maybe—but now I know better. There are some bright spots throughout, but pretty much everything critics said after the album originally came out holds true: The songs, which mostly range between five and nine minutes, are too long; it’s all way too overproduced, like the record’s choking on its own layers of guitars; and Noel’s surreal imagery feels thin and far too lightweight. The sort of nonsense that made Morning Glory endearing doesn’t have the same novelty. Be Here Now manages the remarkable feat of having too much going on while simultaneously feeling like there aren’t enough ideas.

Overexposure led to backlash in the late ‘90s, which is what happened with me in the mid-’00s after my delayed fandom. I had burned myself out on Oasis and was even a little embarrassed by how much I had bought into them. For years, whenever I would listen to Britpop, I’d defect to Blur and Pulp exclusively, and couldn’t be bothered to even revisit “Live Forever,” a song I regularly declared in my teens to be my favorite by any artist ever.

But with enough time and distance, I remembered why I loved the band in the first place—and if a small part of me was still doubting before I saw Supersonic, Whitecross settled that. Early in the picture, when Noel’s working on the songs that would become Definitely Maybe, there’s a section about when he first wrote “Live Forever.” The camera scans across the handwritten lyrics as we hear the guitarist singing an acoustic rendition of his finest song—it’s an incredibly tender and intimate moment, one that convinces you that there really was a bit of magic to this band, saccharine as that may sound.

And scenes like that are what the documentary delivers over and over. In terms of understanding what made Oasis so distinctive and charismatic and important to so many, Supersonic is an essential companion piece to Definitely Maybe and Morning Glory. “When it all came together,” Noel says near the film’s end, “we made people feel something that was indefinable.” That isn’t bluster or bravado or a put-on. It’s simply the truth.