Every classic rock act has its own mythology to be reverently cited by fans of the form decades later, held up as an example of what real music used to be like. The Rolling Stones shot heroin and holed up in French mansions; Led Zeppelin got into Aleister Crowley and may have engaged in bestiality with a groupie; Bob Dylan broke his neck in a motorcycle accident and reinvented himself in absentia; the Velvet Underground shot even more heroin and fucked around with Andy Warhol’s Factory; the Beatles were simply the Beatles.

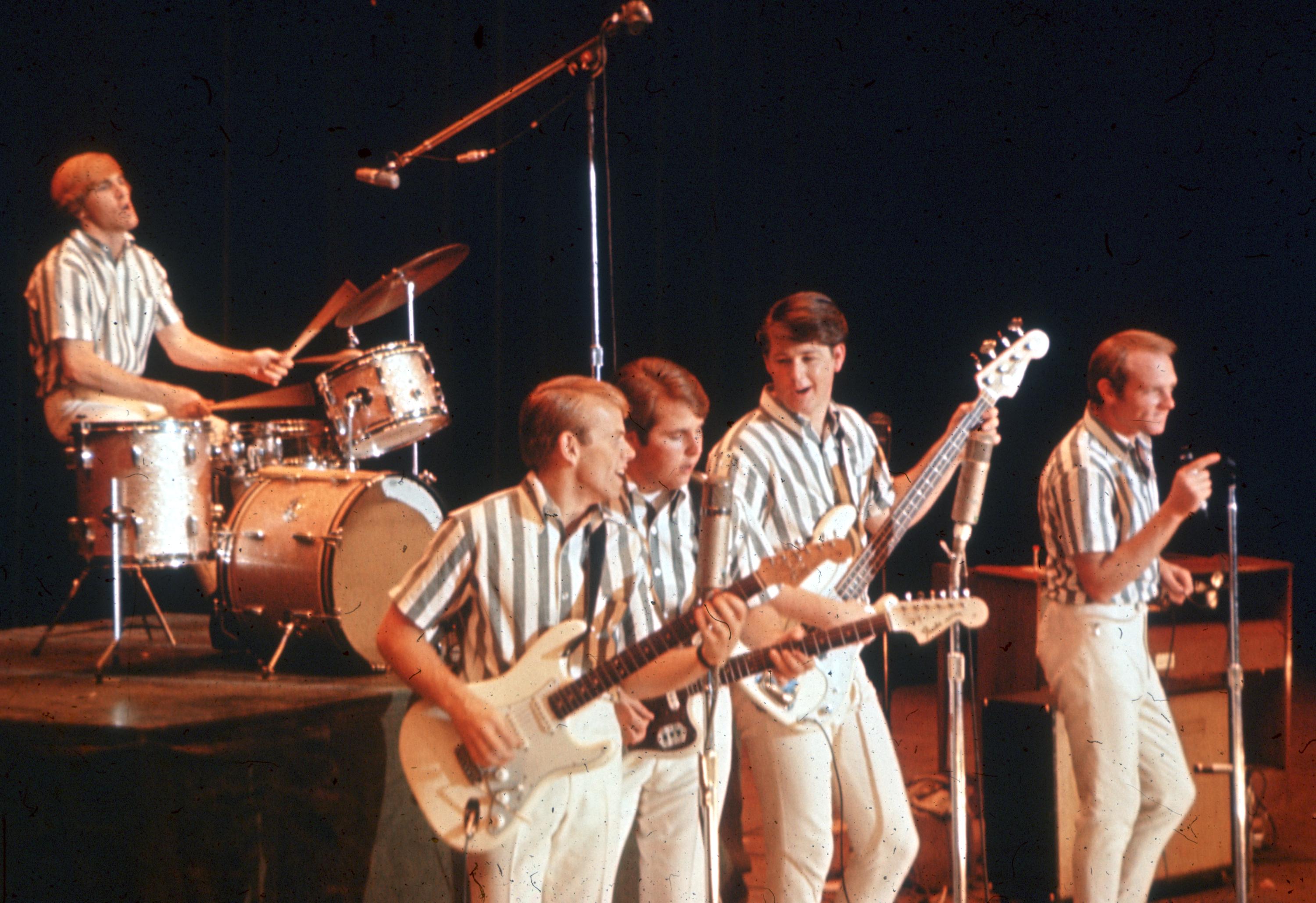

But the Beach Boys are the most iconic band of their era whose story centers around mental illness—whose mythos has evolved in relation to how our culture has typically treated sickness without a physical manifestation. Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison drank themselves to death, and were held up as rock gods. Brian Wilson, on the other hand, lost his mind, and was a punchline for years.

Long before I’d heard Pet Sounds, I heard the jokes about how Wilson was just a little loony. His life story was relayed like a bad boomer acid trip, the details blurring into readymade mythology. He ballooned to 300 pounds during a long, reclusive period; he set up a sandbox in a studio; he abandoned a song called “Fire” after thinking it had actually caused a fire. He was an eccentric, the pop Howard Hughes.

When I was old enough to conceive of Wilson as a living person, not just a cautionary tale, and notice when he slowly re-emerged from obscurity at the end of the ‘90s, it was almost more surprising to me that he wasn’t an overweight, overly bearded, cracked-out weirdo. Where was the Brian Wilson that we had all heard about, and who was this old man? With his lonely little smile, he looked like someone who’d survived.

“Back then, mental illness wasn’t treated in a straightforward way,” writes Wilson in his new memoir, I Am Brian Wilson. “People wouldn’t even admit that it existed. There was shame in saying what it was and strange ideas about how to deal with it.” Now, at age 74, and in a time when talking about mental health in the arts is no longer taboo, Wilson can write about his experience freely. I Am Brian Wilson is a memoir, though because of the drugs he took, both medicinal and recreational, Wilson’s recollection is a little shot, and he isn’t able to present a linear timeline of events. His memories hop from year-to-year, connected not by chronology but by thematic consistency.

The conceit allows him to simultaneously inhabit multiple personas across his life, in order to give different perspectives on similar events: He narrates his life through the eyes of the California child who’s afraid of his father and cries when girls at school reject him; the musical wiz kid who crafts the Beach Boys’ best known songs; the substance-abusing recluse who shuts himself indoors to work on his songs; the near-invalid held under lock and key by an abusive therapist; the recovering icon, coming to grips with his worth in old age. Readers get to spend time with all these Brian Wilsons at once, and the agglutination of experiences is a more engaging, informative read than if he’d just related a linear series of events.

A chapter called “Foundation” opens with Wilson remembering what it was like to play live again in the early ‘00s after a decades-long hiatus. (He’d stopped performing regularly in 1964, following a panic attack.) He writes about the process of growing comfortable with his new band, and learning how to stay centered on the stage. It’s a seemingly benign detail that triggers a memory from a darker period of his life, in the ‘70s, long after he’d stopped performing and was living as a millionaire hermit. A stranger showed up at his house, having gotten his number from Dennis Wilson, Brian’s brother and fellow Beach Boy. “The guy had kind of a surprised expression on his face,” Wilson writes. “Maybe I didn’t look the way he expected.”

Wilson adds just a little bit of commentary on his bedraggled state. He mostly presents the scene as it was, and allows us to observe, from the perspective of the surely bewildered stranger, the chaos of his life. As the story continues, Wilson played “about a dozen songs” for the stranger, before dragging him to a liquor store and forcing him to pay for a bottle of chocolate liqueur he promptly began to drink in the store. Then, they go to a party in Laurel Canyon, where Wilson takes over the stereo and plays the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby” more than a dozen times, even as people at the party asked him to stop. The wacky comedy of it all is underlined by a scary, knowing helplessness–Wilson is the frazzled id, a person of pure reaction.

On cue, the chapter morphs into a meditation on “Be My Baby,” Phil Spector, and Wilson’s approach to music. “It’s like a building going up,” he writes about his music fandom. “You have a foundation, and then you keep adding stories until you look down and you’re so far from the ground that you don’t know how you got up there.” Within a few pages, he nimbly jumps from the recent past to the far past to a series of recollections centered around a single song. The story ends with an explanation of how “Good Vibrations” was written:

People say that the record label and the band thought I was going too far into art music and that I needed to come back to hits. That’s probably true. But that’s not how the song got made. How it got made was that I was high after smoking pot and sitting at the piano, relaxed, playing.

The text benefits from its loose structure–Bob Dylan and Patti Smith’s memoirs did the same–and cowriter Ben Greenman, who also worked on Questlove’s Mo Meta Blues, lets Wilson’s thoughts stand on their own. The writing is impulsive and discursive, and lends insight into what Wilson must be like as a conversationalist in person. Wilson will often say something and correct himself in the next sentence, and the flexibility lends itself to the sort of dad-jokes that make this such a deeply enjoyable read. Like when he brings up the Beach Boys’ Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) LP:

There was another big hit on the album, but I don’t remember what it was at the moment. Oh, I remember: “California Girls.” I was just joking.

Or when Wilson describes a prank he pulled on his dad:

Sometimes I provoked my dad. Once I took a shit on a plate and brought it to my dad. “Here’s your lunch,” I said.

For all his struggles to feel comfortable in public, Wilson comes off as a pretty approachable, affable guy. The book is dotted with tales of casual run-ins with some of his musical peers—the time he thought he saw Carol King at lunch, and struck up a conversation once he realized it was her. Or the time he asked a “young singer” to fetch him a Diet Coke while backstage at an awards show. (“It was Bono. I didn’t know him that well.”)

Because Wilson is universally beloved by his peers, he’s never ruffled about his relationship with anybody; his reactions are both entertaining and instructive about his place in the canon. When writing about McCartney’s love for “God Only Knows,” he says:

Everyone knows now that “God Only Knows” was Paul’s favorite song—and not only his favorite Beach Boys song, but one of his favorite songs period. It’s the kind of thing people write in liner notes and say on talk shows. When people read it, they kind of look at that sentence and keep going. But think about how much it mattered to me when I first heard it there on Sunset Boulevard. I was the person who wrote “God Only Knows,” and here was another person—the person who wrote “Yesterday” and “And I Love Her” and so many other songs—saying it was his favorite. It really blew my mind.

It’s a sweet, earnest way of showing his love for the Beatles—probably the best band ever, despite their Beatles-ness—and the respect the Beatles had for him. It’s not gossip, but still puts fans right in his head. That honest insight remains no matter what interaction he’s describing. Take his run-in with the Eagles’ Don Henley, where Henley asked Wilson to sign a copy of Pet Sounds. The date and location of their run-in is never clarified behind “backstage,” but their cultural hierarchy is already established:

I took a Sharpie from the table in the dressing room. There are always Sharpies around for signing things. I wrote on his record, “To Don: thanks for all the great songs. Brian Wilson,” Don was so grateful. It was almost like he couldn’t talk. He turned to leave. “Hey Don,” I said. “Wait a second.” I took the record back, crossed out “great,” and wrote “good.” Some people would have been mad, but Don just looked at it and laughed.

It’s a little rude, yeah, but he’s only telling it like it is.

In the book, Wilson says he stopped performing because he was never at ease looking out at the crowd, worrying how to please them. But for the last few years, Wilson has gigged relentlessly after getting over his stage fright—and because the Beach Boys are so canonized, each audience is ready to revere him. Last summer, Wilson played at the annual Pitchfork Music Festival in Chicago—I was working for their website at the time—and I watched transfixed as he and his band performed the entirety of Pet Sounds.

At that show, Wilson spent most of the set staring trancelike into the distance, but the songs still sounded lively, and the diversity of the audience’s age cemented his eternal appeal. There was an ecstatic college-aged girl ping-ponging within her circle of friends, making out with whoever she landed on in pansexual rapture. Nearby a pair of sisters passed a pipe that smelled of weed to their grey-haired parents. My friend whispered to me that we were standing next to one of the band members of a popular indie band. We were, and no one cared. He just wanted to sing along to “Sloop John B” like the rest of us.

In hindsight, it’s wild that maybe the greatest living American musician was slumming it in a daytime spot in between, like, Car Seat Headrest and Wild Nothing. But I Am Brian Wilson gives credence to the idea that at this point in his life, Wilson is actually just content to perform music. The book is filled with tragedy—he lingers on the tragic deaths of his brothers, Dennis and Carl; the time he lost due to his manipulative doctor, Eugene Landy; the agony over not being able to complete long-in-the-works passion projects like SMiLE. For him to have made it this far, his sense of self healed by years of work, is a minor miracle.

So often, classic rock icons are depicted as mystical, towering demigods of the culture. In the book, Wilson is down to earth about the fact that he’s Brian Wilson. “There’s always some mystery when I try to remember how I wrote back then,” he says. “My God, how the fuck could I have written all those songs?” Sure, he may have written “Good Vibrations,” but he also struggles with anxiety. He feels bad about his weight. He wants to be a good father; he wants to be loved. Given the egotism that usually infects old men who’ve accomplished a lot, it’s mildly revolutionary to read such a legend be so frank and forthcoming about his weaknesses—and his efforts in getting better.

In 2004, he writes about an incident where a member of the touring band for SMiLE—a record he eventually completed some 40 years later, to massive critical acclaim—was killed in the tsunami that hit Thailand. “We were all heartbroken,” Wilson says about the loss. “But even then I noticed a difference. I was sad, but I wasn’t so down that I couldn’t get back up. I was sad and able to use the things I was feeling to put emotions into my music. That was the way it was supposed to work.”