If alt-R&B disappears ever, it’ll be via suffocation under a heap of its own baggage. The stereotypes are well-known and vicious. The worst of the genre has two modes: shallow or performatively sexualized, the latter salvaged only when nodding to R. Kelly’s ethos of pairing sleaze with earnestness. (Kelly has the decades of musical cred, at the least.) Even the best tends to relegate an entire living genre of R&B and cohort of black artists to prolefeed. But the artists themselves tend to be more complicated than the stereotypes, which is why nearly every musician who’s been tagged as “alt-R&B” or its more ridiculous synonyms has distanced themselves from it, hard: pursuing proggy tangents, disappearing into a bedroom haze, disappearing in general for four years, selling all the way the hell out to Max Martin.

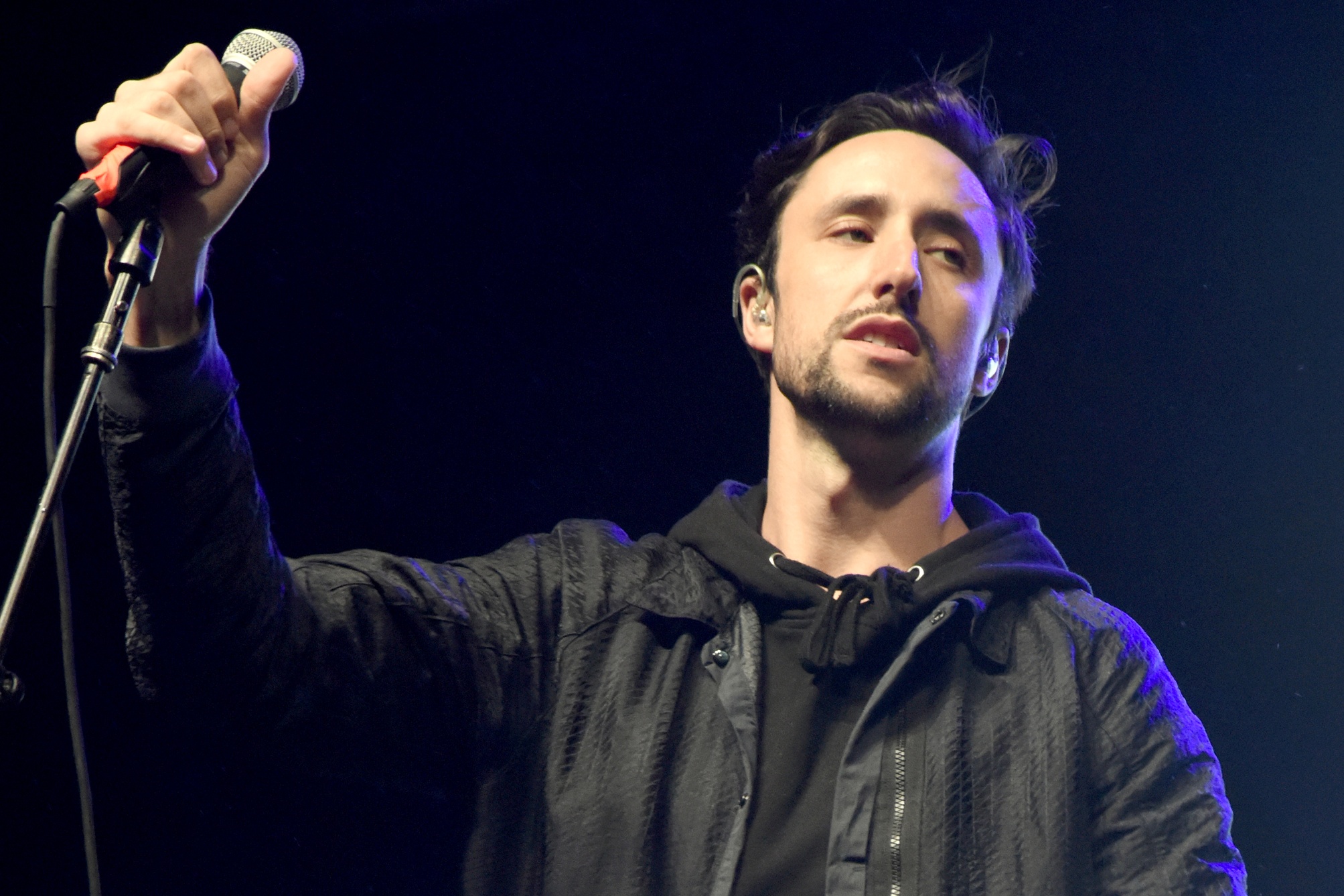

Tom Krell of How to Dress Well is no different: “What would make up a whole song on the first record makes up, oh, an eighth note on the new record,” he told The New York Times about the songs that he’s systematically refined and rethought leading up to his fourth album, Care. Krell may have been known for interpolating (who else) Aaliyah, but the R&B touches were window dressing; his value over replacement blue-eyed soul is in his arrangements—unexpected, threaded through by Krell’s almost-pointillist voice, and better with each album. Which is why it’s baffling that Care’s first track leads not with any arrangement magic but with the most awkward of seductions put to music: “Can’t You Tell,” which aims for, in Krell’s words, “consent pop.” The phrasing around the release certainly carries some implication that R&B as heard on R&B radio was in need of a corrective. It’s a disco track with chicken-scratch licks. It’s also nothing like the rest of the album.

Given sufficient time and opportunity, the arc of every alt-anything artist veers toward pop. For women, this has morphed from novelty to cliché to cottage industry, each crevice of the ‘80s and ‘90s, gaudy to sappy to darkish, exhumed and renovated for another social-media-groomed teen. But as for the men, once you eliminate the Troye Sivan wing of YouTube-mimer electropop and the Ed Sheeran wing of singer-songwriter-splainers, really all you’ve got left doing this sort of thing is Jack Antonoff of Bleachers and fun. Antonoff helms much of Care, and he and Krell share lots of common musical interests: a love for percussion breakdowns, huge soft spots for soft-rock, a willingness to hang all of their awkward, horribly human worries out. It’s a welcome shift. Krell’s voice, thin and hummingbird-skittish, is thoroughly unsuited for mystery but perfect for nervous candor.

A lot of a listener’s acceptance of Care depends on their acceptance for nervous candor; for purposeful titles like “Lost Youth / Lost You,” for earnest existential wonderings of what “care” means, for transcribed 3 a.m. chats about how everyone looks at their phones and how warm skin is awesome and also, by the way, that he really likes your thighs. This has been the How to Dress Well cost of admission for some time now, but Care finds Krell dropping his mental filters alongside the reverb filters—as on “Anxious,” which is now and will likely be into perpetuity the most infectious song containing the phrase “had a nightmare about my Twitter mentions.” (Also, probably the only song containing that phrase, and if that bridge had to be crossed at least it was crossed with a smile and bubbly disco gait. Imagine the angst-ballad it could have been.)

As always, Care thrives when Krell turns his focus primarily to the arrangements—like “Salt Song,” a six-minute omnivorous rush with hints of surf guitar, garage rock and Hans Zimmer; or “The Ruins,” the most overtly “alt-R&B” thing here but formidable enough and striking when Krell drops the mood altogether for a sudden terrified vocal and vocodered, shaking bridge. Krell likes these kinds of switch-ups. “I Was Terrible” threatens to become a high-school talent show ballad—the opening piano riff is one plaintive rearrangement and demographic re-grafting away from Five For Fighting—but gets itself caught in a loop then takes off in a different tempo, the speed of past anxieties skittering and scratching around in the brain until they exhaust themselves.

“They’ll Take Everything You Have” is similarly deceptive: Starts like Richard Marx doing “Live to Tell,” ends as if it’s been left out in the sun. “Untitled” is a piano ballad turned lonely meditation; “Lost Youth” takes an Ashanti melody and closing-credits chord progression and inflates it to twice its size on the bridge. Krell’s explanation of the record’s name, as told to the NYT, may have been tossed-off—gee, the word “caring” sure shows up a lot in English idioms—but the title makes for an apt recommendation: a demonstration of how far one can get by taking life seriously, and one’s arrangements even more so.