August 3, 1995: a day that will live in rap infamy. The Source was hosting its annual award show that night at the Paramount Theater in New York City and all hell was breaking loose. While Suge Knight, the infamous Death Row Records head, garnered the biggest headlines by taking shots at rival hip-hop mogul Puff Daddy and the East Coast rap establishment — on their home turf, no less — another event from that evening that helped shift the geographic focal point for the genre for decades to come. Midway through the show, the Atlanta-based rap duo OutKast were unenthusiastically given the Best New Artist award following the release of their debut album, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik. What should have been a triumphant moment was ruined when the New York audience showered both André 3000 and Big Boi with a wave of boos. Undeterred, Dre stepped to the microphone and let the angry crowd know: “The South got something to say.”

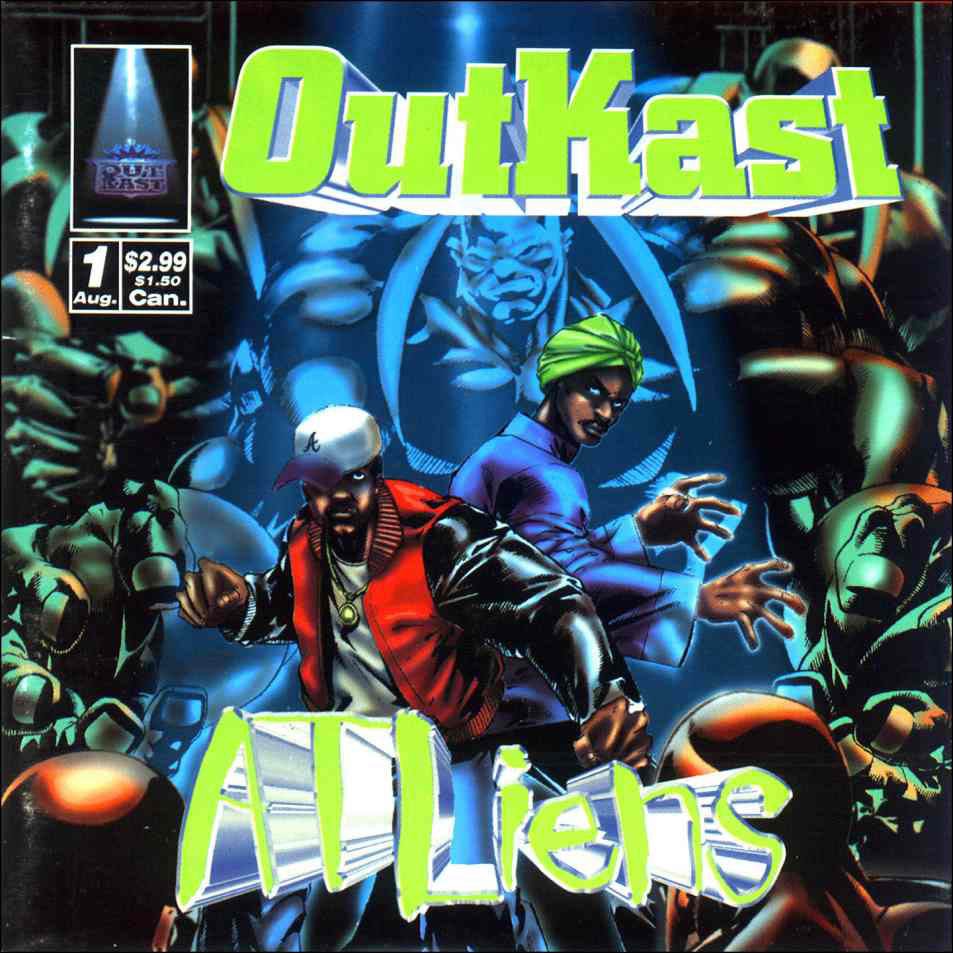

History has proven Three Stacks absolutely correct. In the years that followed, the South (and the ATL specifically) would end up saying a whole lot about the direction of modern hip-hop: Young Jeezy, Gucci Mane, Ludacris, T.I., 2 Chainz, Future, and Young Thug are just some of the big names that spawned from the fertile confines of the 404. But Atlanta’s assault on the charts began in earnest with OutKast, and more specifically, the duo’s 1996 sophomore album, ATLiens.

In the lead up to the album, both members were undergoing serious growth in their personal lives — Big Boi became a father, while André returned to school to get his high school diploma — and maturing as artists. Together, they decided to take more control of their music, handling the production on a full third of ATLiens, including standout cuts like “Elevators (Me & You)” and the title track. The resulting record is as much a classic as the masterpieces that followed, a record lacking much of the frivolity that proved a hallmark of their debut album (and even much of their later work). In its place is a subtle anger and an unmistakable sense of determination: The duo had a point to prove and were intent on making it with precision. “It’s all about growth,” Big Boi says of the album 20 years later. “Maturity. Discipline. Faith.”

To honor the 20th anniversary of ATLiens (the album’s birthday is later this week, on August 27), SPIN rang up the rapper born Antwan Patton to get a better idea of what went into the creation of ATLiens, and how the LP helped shape the future success of the greatest duo in rap history.

How much did the success of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik change you and André?

We were teenagers. So Southernplayalistic, it gave us a chance to see the world. We traveled a lot and performed all over the world. You know, you got two teenagers from Georgia who hadn’t been past South Carolina or Florida seeing Europe, and the West Coast, and New York. It kind of broadened our horizons. The world is bigger than where you live.

You guys went on a trip to Jamaica around that time that is said to have had a pretty big impact on the group.

I didn’t make that trip. Everybody else in the Dungeon [Family] went. Unfortunately, my Aunt Renee — who was my guardian at that time — passed away, so I missed that trip. I spoke about that on the song “Babylon” on ATLiens. They all went to Jamaica and everybody came back with dreads and it was like, “S**t.” But, I was grieving at the time, so I morphed into something else.

Another big change around then: You became a new father between the release of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik and ATLiens. How much did that affect your outlook on the world?

It made me more responsible. My daughter became my number-one priority. It was like the papa bear and his cubs. You would do anything to protect that baby and anything to provide for your family.

I had to learn how to balance recording and being a father. I’m glad I did, because it’s [my daughter’s] senior year at Auburn University and me and her mom and her uncles went down there — we don’t use movers, so we moved her into a brand-new townhouse for her senior year of school. She was just so overjoyed because I went down there to register her. I’ve been on tour and been busy, busy, busy, and this is my last time toting mattresses and sofas and doing the real daddy thing. To see my baby making A’s and B’s and majoring in psychology…

Dre [would] always be like, “I love how you just buckled down.” Like, “Man, goddamn you’re serious about that daddy s**t.” I’m blessed that God put me on this path. It also brought a sense of restraint. Just not being out here wilding.

Did recording and writing feel more like a job after that? Like, “This is how I have to provide for my family?”

Absolutely not! This is not a job, this is a way of life. If you look at this s**t like a job, are you an artist? Sometimes it might seem like hard work, because I really put a lot of time into my pen space. I’m serious about my craft. But it’s not a job — if anything, it brought more joy into my life, more sense of purpose. That’s why nobody can’t f**k with me now: I’m the baddest motherf**ker on the planet. Believe it! Jedi rap s**t all day!

It’s been talked about a lot, but at the Source Awards in 1995, when OutKast got booed and Dre said, “The South’s got something to say” — did that event fuel you guys to prove that rap in the South was just as vital and important as what was going on on the coasts?

I call it the rap civil war. We were the first ones to break through to the North and have them respect us as MC’s, our craft, our ability to write lyrics, and have bars. They had to respect it. He spoke it at the award show because they booed, but we didn’t give a f**k. It pissed us off, and they shouldn’t have did that, because it fueled us and threw gas on the fire. But we were already thinking that, because we had to fight so hard to be recognized.

Going along with that, on “Two Dope Boyz (In A Cadillac)” you claim that you only rap “to prove a point.” What were you trying to prove?

The point that we were proving is that we’ll eat your ass up. We some real MCs. Black dog and black wolf is what they called us in high school. Just lyrically dominant, and it’s still about that. I stay recording and I’m halfway done with my next solo record, which someone is saying is one of my best records ever — it’s some of my best work to date. I think it’s going to shock a lot of people.

On “13th Floor/Growing Old,” you talk about phonies pretending to be pimps riding around in a Mercedes-Benz. Were there that many phony rappers around at that time?

You know, I take a page out of KRS-One’s book: You can entertain and educate at the same time. Give them a little bit of soul food in there, you know? It’s okay to party and make all the party records in the world, but once you start to make people think, then you really got their attention.

I think one thing that [demonstrated] that whole state of mind is when we did “Git Up, Git Out.” A countless amount of people around the world were like, “That song motivated me to go to college.” “That song helped me get off drugs.” “That song helped me be a better person.” We didn’t know about that when we were making it. It was just our mind state. But to know it affected people’s lives like that? There’s a sense of responsibility.

Can you talk about how the process for the recording of ATLiens came together?

We went on tour and Organized Noize rented out the top floor of the Biltmore Hotel in Atlanta. They were camped out in there with all kinds of beat machines, and by the time we came home, they had already started laying the foundations to the album. By that time, we also had already started producing songs like “Elevators.” We learned from being under them for so long. What better way to paint a picture than being able to create the soundscape for your words? We were maturing and coming of age then. Just trying to figure out, “Where are we going?”

Organized Noize are one of the most respected production teams in rap history. What did you learn from them and what did you think of the material that they presented to you when you came off tour?

Organized Noize is the Jedi Council. They brought us in and molded us. To this day, I still work in close quarters with the members of Organized Noize. Me and Ray Murray are great partners. He’s camped out at Stankonia Studios, my studio, every day. From all my solo work to the Big Grams album, there’s always been an Organized Noize presence. Sleepy Brown, he lives in Vegas now, but he comes to Atlanta. He’s all over my next record. We just learn from each other and try to make the best music possible.

The production of five of the tracks on ATLiens are credited to both you and André. Can you talk about your philosophy as a producer?

It has to have feeling in it. When you’re listening to a track, before you put a word on it, it has to make you feel a certain way to inspire those words. There’s no competition about it at all. The only people we competed with is ourselves individually. It’s like Dre said on “Mighty O,” you’re running from a shadow because you’re competing with yourself. That’s how you push yourself to be better.

Two of the biggest standouts from this album were produced you and Dre: the title track and “Elevators.” How did you build both of those tracks?

A lot of those things just come from casual conversation. Just beating on the beat machine, tinkering around with little stuff in the studio, finding a rhythm, and then we’d just kinda sit there…I really wish we had, like, eight Go-Pros in the studio so I could look back at and see how the moments and things, how stuff happens. It’s truly magical in the sense of… the s**t comes. That’s why I say it’s a gift. It’s not forced, contrived, or nothing.

I read that you guys went out and bought an MPC3000, an ASR-10 synthesizer, a Tascam mixing board, and a drum machine to create the beats. Does that sound right?

Yeah, we both bought our equipment at the same time. When we did our publishing deal that was the first time we got some real paper and we went and invested in ourselves. We wanted equipment, we wanted to make beats, and we set up our home studios in our apartments, and Dre at his dad’s house. That’s when Dre was rolling me like 30 blunts a day. I didn’t even know how to roll a blunt and he taught me how. We would just be in there, smoked out, just banging on s**t.

It’s said that you guys recorded something like 35 songs for this record and then eventually whittled it down to 15. What happened to the rest of that material?

A lot of it trickled down into other records. That’s the thing about making timeless classics. There’s no expiration date on it. Some songs that didn’t make Southernplayalistic ended up on ATLiens, some songs that didn’t make it onto ATLiens ended up on the next record, and the next record. I know “West Savannah” [from 1998’s Aquemini] was on an earlier record and came out later.

In contrast to most of your later albums, ATLiens has a much darker, more intense vibe throughout the songs. Is it safe to call this your “serious record?”

I wouldn’t say serious; I think it was a mature evolution. We didn’t know what the music business was. We were just two young cats that wanted to destroy everything we got on. Once we started traveling, doing interviews, being in front of the TV, you started to know the system. From that comes maturity. You’re also going from a teenager to being 20 and you’re looking at life differently because you’re having different experiences. It wasn’t more serious, but we weren’t kids anymore. A lot of people don’t realize that we’ve been doing this for so long, but we started so young — like, 16 years old.

Being that it was such a tremendous shift away from the sound of Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, were you at all worried that your fans wouldn’t accept ATLiens like they did?

We weren’t worried, the label was. They didn’t even like “Elevators.” They were like, “Y’all crazy!” We said, “F**k that s**t,” and took it to the radio station against everybody’s wishes and it blew up. From that point on, L.A. Reid let us pick all our singles.

You and André have such a unique way of weaving around each other’s verses. Can you talk about your writing process a bit? How you break up a song? Did you guys write eye-to-eye?

Southernplayalistic was definitely eye-to-eye. One person would get far and be like, “I got it!” And then it’d be like, “Go ahead and lay it.” Then I’d do my part. “Oh s**t!” You’re inspiring your partner, bouncing that energy back and forth. That’s what makes the group so unf**kwithable. You have two sides of the same coin with different points of view. The s**t fun, man.

The Cadillac is like the official car brand of OutKast — it’s in the title of your first album, you’ve got “Two Dope Boyz (In A Cadillac)” on ATLiens. How many have you owned over your life?

Cadillacs? I’ve had a ’90 Brougham… Dre bought a baby-blue ’90 Brougham, and then I bought a root-beer-colored ’90 Brougham and I loved it. I ended up giving it to my grandma, so then I bought a ’79 Seville — canary yellow. It’s in my mom’s garage right now. I’m about to pull that bitch out before it gets cold outside! [Laughs.]

So I’ve had two Cadillacs, but then I got into Chevy. So I have a 1960, ’61, ’62, ’63, ’64, ’65 Impalas. Killer Mike swindled me out of my 1960 mint-green Impala, and I sold him a Red ’63 Impala. We’d be on the bus in some kind of way after everybody got a drink and [he’d] be like, “Lemme buy that car from you.” Then he’d give me the money on the bus, and when we’d get home, the car would be gone. So he got me two times, but he won’t get me again! Then he sent me all the pictures of the new paint job and the motor and s**t; I don’t wanna see that s**t.

Have you been working with him at all lately?

Boy, absolutely! Wait until you hear this new s**t. Killer Mike is busy as hell. I mean, he’ll come straight from the airport and go into the studio and bust on two or three records and come back again the next day. We’re just trying to put as many ideas out there as possible. And me and Killer Mike, we’re gonna put out a little EP after I put out my next solo record or something like that. We’ve been entertaining the idea for a long time and finally got enough songs to where we just said the other night that we’re gonna do it. You getting a scoop there.

Getting back to ATLiens, when it finally dropped in 1996, it went No. 2 overall on the charts, was certified double-platinum, and is now widely considered to be one of the greatest rap albums of all time. What did that kind of success feel like, and how did it impact the way you approached the next album, Aquemini?

I don’t think we really realized how big ATLiens was until we put out Aquemini. It’s like the following was growing and growing and growing. We sold over a million records every time. The ATLiens album just spoke to people. People who were in our same age group [who] were teenagers during Southernplayalistic followed us to ATLiens. They were on that same journey.

If you had to pick a favorite song or a favorite verse from ATLiens, what would you choose?

That’s like trying to pick which one of my kids is the best kid. It’s all one thing. Day to day it might change, depending on the mood I’m in. One day it might be “Wheelz of Steel.” One of my favorites is “Ova Da Wudz” because I love how we did lyrical gymnastics all over that bitch. But, you know, it changes from day to day. I just put my iPod on shuffle.