“The format is there is no format.”

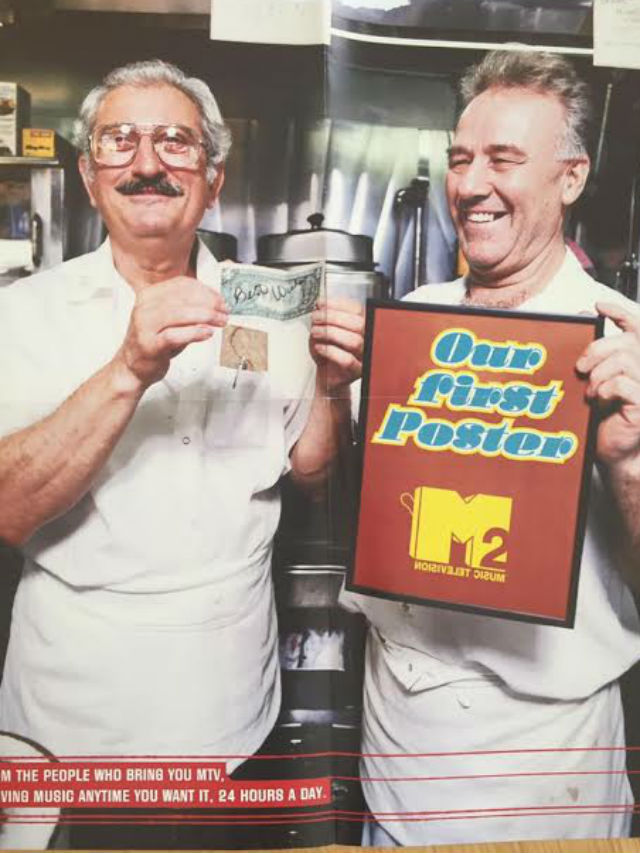

With that seven-word paradox as its unofficial, Seinfeld-ian mantra, M2 launched on August 1, 1996. The MTV spin-off channel began with a similar spirit of rebellion and innovation to its predecessor 15 years earlier (to the day), but with significantly humbler ambitions — the channel was mostly designed to hush critics of M1’s then-recent shift away from music videos, and fend off potential competitors at the same time. (It also began with an even-smaller market share — the station was available only to consumers who watched TV via satellite.) But because of the lower stakes involved, M2 was able to present viewers with a utopian vision of music television that early MTV dared not dream of: a 24-hour, commercial- and programming-free music-video network, with a near-infinite inventory to draw from — shown by producers and video jockeys who cared only about music, and who were given no mandate to sell or promote anything.

Simply put, M2 was to music television in the ‘90s what Beck’s Odelay was to the decade’s alternative rock: an irreverent, free-form work of tossed-off, genre-spanning genius, one that stripped all the pretensions and self-seriousness away from the increasingly bloated art form in favor of something ten times smarter and 20 times more fun. (Appropriately, “Where It’s At” was the first video the network ever played.) Partly out of financial necessity, the channel embraced the spirit of the amateur — VJs were hired for their lack of experience, sets were chosen for their authentic New York griminess, and commercials were allowed to be as esoteric as the burgeoning auteurs filming them desired.

But for video devotees, M2 was beyond fantasy. Rather than adhere to the strict playlist structures of the mothership, the channel indulged the every whim of its music-nerd programmers, jumping free-associatively from one video block to the next. The channel was just as likely to be showing an absurd new clip from ex-Pavement drummer Gary Young as it was to be playing a forgotten classic from A Tribe Called Quest. There were no constraints on the playlists beyond those that the programmers put on themselves, and the possibilities were limitless: If the channel’s brain trust wanted to play a full day of videos that started with the letter “Q,” they could, and they would. In a pre-YouTube world, where the entire history of music videos could only be accessed through what the gatekeepers at MTV and its sister channels (VH1, BET, CMT) allowed, discovering M2 was like growing up with just a couple dozen CDs and then suddenly being given a Spotify account.

Of course, it couldn’t last. As inevitable commercial pressures finally beckoned, the channel officially rebranded from M2 to MTV2 before the turn of the century, and by the time it was finally made widely available to digital-cable subscribers in 2001, the station had introduced commercials, genre-segregated video programs, an added emphasis on new and popular music, and an entirely new roster of VJs. By the mid-’00s, it had started to shift away from videos to non-musical original programming and MTV leftovers. Today, the channel is predominantly populated by reality shows and sitcom reruns, showing music videos only in the late-night and early-morning hours, with about as much in common with the original M2 as A Moon Shaped Pool has with On a Friday. It’s a path that every music-based network now seems doomed to follow — as VH1 Classic’s recent transition to the programming-focused MTV Classic has demonstrated, even the nostalgists are losing interest in music videos.

It’s why the history of M2’s earliest years, as the channel was first envisioned (to be the purest 24-hour music-video network that we’re likely to ever see), seems more important than ever to be told, and remembered. It’s the story of a channel that enraptured rock stars like Dave Grohl and Bono, a channel that broke the Spice Girls and LeAnn Rimes in America almost by accident, and a channel that ended up disproportionately popular in the American penal system (more on that later). And so, most of the network’s key behind-the-scenes people and all three of the original VJs jumped at the chance to talk to SPIN about the station they put together as a group of music-obsessive friends who couldn’t believe their dumb luck.

Here, in their own words, is the story of the greatest music video network of all time.

Andy Schuon (Executive VP of Programming, MTV): I was hired [by MTV, from Los Angeles rock station KROQ] in ‘92, and in a matter of months I ascended in the programming department of MTV. In a year or two I became the head of programming of MTV. I was overseeing VH1 and MTV, and then ultimately was tasked by [station presidents] Judy McGrath and Tom Freston to develop MTV2, which we called M2 at the time.

Nigel Cox-Hagan (Producer of On-Air Promotions, MTV): I remember MTV had [recently] started — and it seems kind of silly to think about it now — to add programming that was not music. As cool as music was, and as important as it was for the brand, it didn’t rate. And the pressure had increased for them to create more things that were closer to traditional programs, and they did.

Andy Schuon: In the mid-’90s, part of my programming plan was to grow more original programming out of TV. If you recall, it started [in ‘92] with The Real World, and then there was Road Rules, and all the other programming at MTV — Beavis and Butthead and all that stuff came on during my time there, as we were starting to take away more and more hours of music.

We wanted to be able to control our own destiny. We really lived or died by the quality of the content at any one time. We didn’t make the music videos, we didn’t direct them, we didn’t tell [artists] what kind to make. We just had to sit back and wait to see what we got. So the more programming that we created [ourselves], the more intellectual property we owned, and the more ancillary products we could make — like the Beavis and Butthead [Do America] movie. We could come out with a Real World coffee table book. It was easy to do that sort of stuff with our own products.

Jancee Dunn (VJ, M2): Given where I worked, at Rolling Stone, I did what everyone else who thought they were cool did, and just complained all the time about MTV and how it had gone to Beavis and Butthead. I had basically stopped watching the dating shows and all that. The music really did disappear.

Andy Schuon: My job was to be the chief diplomat between MTV and the music industry, and I remember telling the record companies — Clive Davis, Tommy Mottola, Russell Simmons — that we were still playing over 1,000 videos a week. We were still playing hours and hours a day of music. But it was less and less, and it was a very sensitive subject.

Nigel Cox-Hagan: We understood that [the new channel] was meant to be the answer to the question of “Where has the music gone from MTV?” Certainly they didn’t want it to be a rebuke or criticism of MTV — they wanted it to be a reignition of the spirit of adventure, and they really wanted it to be about a pure music experience. This network was meant to be about the music.

Andy Schuon: There was a decision made for a consortium of labels to get together and try to make their own music channel. It’s sort of like how Sony and Universal launched Vevo four years ago. The first conversation [we had] was about essentially showing the record industry how difficult it was to launch a new music television network. We thought, “Well, let’s get out there, and when they see how hard it is for us to get another channel distributed, then they’ll really question [doing it themselves].”

We went out to the market and the reality was that a lot of the cable companies said, “We’re really hesitant at this juncture to carry another music channel,” because there was MTV, BET, VH1, and CMT at that time. The digital channels weren’t launched yet. And so I was able to go back in my diplomatic role at MTV and report back to the record companies that we were having a difficult time getting people interested in it. However, [the cable companies] did say, “If we were to carry another music channel, we certainly would want to carry one from MTV.” I was able to deliver that message.

Darcy Fulmer (Music Director, M2): It was when digital cable was like, “Stake your claim, get in here and get your channels, figure out what kind of programs you want to put on them, and get as many as you can.” It was just so early on. [Andy] didn’t even really know what it was going to be at all.

Andy Schuon: There was a time when we had to decide, “How is this going to work? How is M2 gonna be different than MTV?” This was a big discussion and it really rested on my shoulders in terms of what was the music going to be. We knew it was going to be all music. [But] being a pop station for M2 didn’t make sense, and that would have a very broad appeal. We didn’t want to be an urban station, because then we would just be a better or worse BET, and we didn’t want to be a country channel because we had CMT. We couldn’t go up in our [age demographic] because we had VH1. We couldn’t go younger because that actually could cannibalize MTV in some ways. So that left us with a predicament. What do we do?

I was talking to [MTV consultant] Jeff Pollack, and I had a meeting with Tom Freston in — I’m not exaggerating — like, five minutes. I had to tell Tom at that point what we were going to do. It was game time. And I said to Jeff, “MTV is programmed with numbers, with rotations.” We have our A-rotation videos, maybe five or seven videos that are the biggest, then a medium rotation. Just like a radio station, we scheduled the music so that the biggest things played every hour and 15 minutes and the other things played every three hours, [and so on]. It was all math, and it was very much like radio. So I said, “MTV and radio is programmed with math… How about if M2 was free-form? What if we made it with thought instead of math?”

I hung up the phone I went up to see Tom Freston, and he’s basically like, “So what are we gonna do?” I said, “The format is there is no format.” He’s like, “I love it.”

Darcy Fulmer: So it was just [decided], we’re gonna do a 24/7, complete music-video, purist music channel. Play new music, play old music, play whatever. And then [match that with] really avant-garde promos and packaging.

Nigel Cox-Hagan: I worked on [the channel’s look] a while with a number of people in the company — designers and writers — and a couple months later, I pitched the idea to Tom Freston and Judy McGrath for how we would brand this new network. We definitely wanted to be kind of an un-brand. In the arrogance of youth, we wanted to rebel against MTV, which of course represented a form of rebellion itself. We wanted everything about the network to not be a rebuke of MTV, but definitely be its daring cousin or sibling.

The use of the record-label idea as the platform for the logo came about as a way of representing that it was purely about music. And I believe we spun it on its head, so it would be at odd angles, to give the idea that our viewpoint on music was different, odd, and adventurous. We thought, “Well everybody’s so mad about MTV not playing as much music anymore, we’re gonna have to be total rebels. We should just name ourselves ‘M’ — you know, M2 — and just be purely about music.” Now I kinda laugh at the sheer gall I had.

I will say it’s to the credit of the environment MTV had at the time that we could pitch this to all the senior executives at the company and they would endorse us going forward with this logo. That’s one of the things I really enjoyed the most about that environment — how creative it was and how willing to take risks and experiment.

Andy Schuon: I remember thinking it was really smart that we were calling [the channel] M2 at the time. It was going to have a similar look and feel in a logo, but it would be different. It wouldn’t be called MTV, but you would know it was MTV. I remember we were all pretty sure that was the right decision. I think one of the reasons was that there were all these other channels starting to pop up and make second versions of things — ESPN2 and things like that — and we thought it lacked creativity. It was really important to us to make sure the same kind of authentic brand-building that went into MTV went into M2.

Lou Stellato (Senior Producer, MTV): I was brought on [as senior producer] to oversee M2. It was a little scary because I was given certain restrictions, but it didn’t stop me, and it was an exciting sort of idea. And the fact that it was sort of being given this… it wasn’t really a soft launch, but it wasn’t this major-universal-announcement kind of thing. When something isn’t paid that much attention to, there’s a lot more freedom, and that was an exciting thing to have.

I only had a month, by the way. I had a month to get the channel on the air. I was coming back two months early [from MTV’s Beach House] and I had no place to live. So I was staying in a hotel near the office, which was perfect because the hours were really long. Not only were we launching a channel, but I was also helping to train the people who had never worked at MTV, and I also had two people who had never been VJ’s before.

Jancee Dunn: I had been [a writer] at Rolling Stone for eight years, or something like that. A friend of mine who worked in TV said that they were looking for VJs [at M2], and she said, “Why don’t you try out?” She said that they were really focused on people that knew their music, and didn’t just want talking heads or foreign models or whatever, which I certainly am not. So I thought, “What the hey?” I went over and tried out.

Kris Kosach (VJ, M2): I was in the right place at the right time. I had sent this tape in [to MTV] and unbeknownst to me, unbeknownst to everybody really other than just a handful of people in the music and programing department, they were creating this thing called M2. They were looking for people who knew a lot about music, and my tape just happened to be there. I was a huge audiophile and knew a lot about music at the time, and they brought me up a couple times. I must have commuted back and forth between St. Louis [where I was a radio DJ] and New York two or three times for second interview, third interview, fourth interview. And they would throw some zingers at you [to figure out] what you knew. I guess I answered correctly.

Jancee Dunn: I went for the audition and it was outside of M2, it was kind of in a parking lot, in the back near some warehouse or something. They just threw me outside and I was very nervous. I started breaking out in hives all over my neck, which is not a sexy look. They had to keep stopping tape and saying, “Okay, she’s got hives again. Makeup!” The makeup person would come over and spackle my hives, and I said, “Oh, I aced this! I’m definitely getting this job.”

Matt Pinfield (VJ, MTV): At this point, I was doing [alternative rock showcase] 120 Minutes, and I was also doing other shows. They were starting to put me out on the stage, but I was still also in the music department, partly in programming. I remember Tony DiSanto came up to me and said, “Listen, man, we’re looking for someone like you to be on M2. We’re starting a second channel that’s going to be completely music-centric.” Then, a few weeks later, he says, “We’re still looking for someone like you. If you have anybody that you could recommend or that you have in mind, in your vibe…” And then a few weeks after that, he said, “You’re gonna be doing it.”

Jancee Dunn: I’m not being disingenuous when I say I was shocked to get the job, because they wanted a regular person. A real person, and a person that knew something about music.

Kris Kosach: It was just the three of us in the beginning. They had hatched this plan, and they were just looking for people who really knew a lot about music, and they thought that those three directions — Jancee, me, and Matt — would be enough. And then after that, people started knowing more and more about M2 and wanting to get on.

Andy Schuon: It was fun for me and my team because we got to be the founders of another MTV, for our generation. This is 15 years into MTV. Bob Pittman and John Sykes and Judy [McGrath] and Tom Freston, they got to make MTV. Now me and my team, we get to make M2. So it was really an exciting thing to be able to launch our own rocket.

Jancee Dunn: I definitely wanted to be a part of it. At that time, I was not too long out of college, and nothing was more fun than watching music [videos] for hours and hours and hours. It was great! We’d say, “Okay, one more video, one more video.” And then it’s 4:00 in the morning! That was my lifestyle. I could have lived like a mushroom in that point in time, in my dank apartment. And also, people like Matt Pinfield would sit there talking about music, and I already did that all day long at Rolling Stone, so that was definitely my comfort zone.

Matt Pinfield: I mean, I loved being part of regular MTV too, it [gave me] a national profile. Both of these channels did. But being on the ground floor of something brand new that’s being launched is very, very exciting.

Jancee Dunn: We were thinking, “Every cable company in the country is going to buy this. It’s so cool, it’s so great! So many colleges around the country, and every college student is going to want to get baked with their friends and watch it every night. It’s going to be enormous!” That’s what I thought on launch day.

Lou Stellato: There was so much crap that went into taping that first week — deciding what the first video would be, all of that.

Darcy Fulmer: We spent weeks and weeks on the whiteboard [deliberating the first video]. It was in our music department room and people would just write stuff on there. When you walk by you’d be like, “This is my choice,” and then everyone would always go, “No way.” We were very much like brothers and sisters in that there was no professional courtesy. We had no problem going, “That song is terrible.”

Matt Pinfield: It was really supposed to launch with us playing “It Takes Two” by Rob Base [& DJ E-Z Rock], or something like that. I remember that was one of the original conversations that we had.

Darcy Fulmer: We really thought about “It Takes Two” by Rob Base for a long time. But then we just felt like it was an old video. Here’s a new channel and you’re playing a video from the ‘80s… it just didn’t seem right. If it had come out that month it would’ve been perfect. There would have been no question about it. So when it came to Beck, we just felt like he represented so many genres of music as one person — he wasn’t alternative, he played folk music, he dabbled in the hip-hop sound a little bit… and it was also “Where it’s at.”

Kris Kosach: The logic to that was the name of the song: “Where It’s At.” They wanted M2 to be where it was at.

Darcy Fulmer: We definitely agonized over it. The whole first hour: Beck into Maxwell, “Ascension,” into Soul II Soul, “Back to Life.” We agonized over that.

Watch the first hour’s worth of music videos played on M2, including some popular M2 promotional spots of the time, in this YouTube playlist:

https://youtube.com/watch?v=videoseries%3Flist%3DPLHPtYW9zZTbrumY-7iv6wSLWfXeSHNved

Lou Stellato: The actual launch day, there was a party at a bar in the Meatpacking District, and it was a basement bar and I forget the name of it. It was like the Locker Room, or the Freezer Room or something.

Kris Kosach: I believe it was at a club called the Refrigerator. I don’t know if that’s still a club or not, but it was downtown and there were so many executives shoved into this dark, dank little basement. We were all really excited the moment it came on.

Andy Schuon: We could not get the signal to the party. So what we did was, at precisely the moment the channel was to launch, we hit play on a VCR in the club, and we played it off of VHS, while it went out on satellite to other points.

Darcy Fulmer: It definitely was low-budget and fit the tone of the channel. But everyone came. All the higher-ups, everybody came to it. It was really exciting because we just felt like it was something brand new. And all of us who worked in the music department were music fans, so it was a complete dream come true that we had this thing we could put all the songs on.

Kris Kosach: Darcy Fulmer, I’m gonna give her a lot of credit. She and her team and the whole music department, they were the geniuses who came up with this free-form idea. So we would literally go from Nine Inch Nails into Johnny Cash. And then we play LeAnn Rimes, and then we play RZA, and then we play Björk, and then we play something rockabilly.

Jancee Dunn: The great thing about M2 is that it wasn’t like they only had to play indie stuff. I love bad late-’70s/early-’80s R&B. If it has an embarrassing name like L’Trimm, Oran “Juice” Jones, I love that stuff. With M2, they would mix that stuff in! It was done unironically — if you wanted to just see “Get Off” by Foxy, you could see “Get Off” by Foxy! It was just fantastic.

Darcy Fulmer: We would make the M2 playlist at the same time we made the MTV one. we would watch all video submissions for MTV and M2 and then we would decide where they were gonna go. MTV rotations were much tighter because there was Yo! MTV Raps, there was MTV Jams, AMP… there were specific shows where things fit into a certain tone of whatever that show was. M2 was just like, “It’s a cool video, okay.” It didn’t have to be any format.

Jancee Dunn: If you had a personal preference — and by you I mean anybody, we were so under the radar — that if you had your personal favorites, you could totally play them a whole lot more. I remember taking a video by Sneaker Pimps and saying, “Look, can we throw this on heavy rotation? I just want to see it and hear it more often.” “Sure thing!” It was so easy. If you had a song in your head that was on the radio all the time, you could say, “Put on that Kula Shaker song!”

Darcy Fulmer: Sometimes the super-young kids [at the network] — I was young then, but the ones who were just out of NYU film school for six months — would be like, “This should be cooler.” I’m like, “As soon as you say what it’s supposed to be, you failed. It is never supposed to be anything, so if you’re gonna come to me and tell me, ‘Well, we should be this,’ you’re out.” Sometimes people would say that, and I would go play five Billy Joel videos to show everybody.

Matt Pinfield: What was really fun about it too, in the beginning, was we’d do a half hour with songs that had the word “blue” in them, or a half hour of ska, or a half hour of synth-pop.

Andy Schuon: If we’re playing a female artist, maybe we’ll play three hours of female artists. Maybe we’ll play 90 minutes of ‘80s music. Maybe we’ll play all metal for a whole week. If it’s Black History Month, maybe we’ll play a whole month of hip-hop. We’ll do whatever we want, but we’ll have our programmers think about current events. We’ll think about what’s happening in music and around us, and have M2 reflect that.

Darcy Fulmer: Sometimes people in production or other people at MTV would suggest, “Oh, I have an idea!” Or if we got a [new] video submitted, they would be like, “Oh that looks like blank video. We should do a whole hour of those.” I used to come in sometimes and go, “I’m just going to play black-and-white videos tomorrow.” And that’s what I did.

Jancee Dunn: One time, I did ‘80s pop music with saxophone solos. I think I did ‘80s R&B betrayal videos.

Lou Stellato: On my birthday, I programmed six hours.

Darcy Fulmer: When Details magazine launched, it had “What’s In, What’s Out.” And they had “What’s In: M2, 24 hours of music videos, cool music,” whatever. And then it had “What’s Out: M2, because you know eventually they’ll screw it up.” And I took that and I hung that on the door of my office for whenever anyone gives me grief. People already wanted us to sell out or suck. And by the way, if I want to do a sell-out day, we will. Because we can and we should.

Lou Stellato: I think the overall direction was to keep [the focus] music-centric, obviously, but keep the VJ segments really fun and informative. And to keep it as lo-fi as possible, so that it felt really homemade in a good way.

Kris Kosach: We had scripts when we went out there. But then I discovered that Matt would show up and he’d say, “Ah, to hell with it,” and he’d just go and be, “Hey!” So then I started doing that too, and it turned out to be a much better situation when you didn’t have to go on script. We all rebelled and kind of started making it our own, and [the producers] loved it when we just went off script.

Matt Pinfield: We were only to break twice an hour, so we would talk about things we [had shown] before, and then things that were coming up. They would hold up the titles — for me, they wouldn’t write anything much. I would just riff. People would go, “Boy, he’s saying a lot, they must have a lot written on that card.” [It was only] titles of the songs.

Lou Stellato: Matt was a known quantity — once you put him on camera, he’s on autopilot in the best way possible. He knows what he’s doing. But with Jancee, she was so terrified. She was sort of reluctantly agreeable, and that was so much fun to play with and see on camera.

Jancee Dunn: [Lou and I] would get in arguments. I would beg him. There was classic footage of me saying, “Please, can we turn off the camera? This is really going downhill and I’m beginning to sweat an awful lot. I can feel the hives coming out. Let’s just do it again!” And then he wouldn’t even say no, he would just shake his head. He was torturing me! But he loved it.

Lou Stellato: I was an on-camera voice, where she would stop the segment and say, “Oh my God, I just said the stupidest thing. Can we please do that over?” and I would just say, “Keep going,” and that kind of stuff would air. I don’t know if I ever elaborately planned anything, but she was afraid of dogs, so if there was a stray dog on the Lower East Side that suddenly barked and leaped at her, you know we’d keep that in.

Sheree Lunn (Makeup Artist, MTV): Before I met Jancee, [Lou] explained to me her personality, and [how] she wasn’t an L.A. girl that has that kind of look. She was more of a music person, and real-looking, and he wanted her to stay that way on air. That was pretty much his guidance, and as soon as I met her I totally understood what he meant.

Jancee Dunn: I continued to get hives. And adult acne, well past the age that I should have. Because I just never got used to how nerve-wracking it was to interview people. I was used to doing my thing as a journalist, with me and some other person in a room. Often for these video shoots, [artists] would show up with their giant entourages. We did André 3000 when he was in OutKast, and I remember that I was really nervous for some reason. I got adult acne on my forehead to the point where it was almost like a unicorn horn. And they were all joking around, saying, “Don’t look at Andre directly, because if we look at you in profile, it’s going to look really strange.” So I did the interview staring straight at the camera, which was a little awkward. They had to keep spackling me.

Lou Stellato: I loved Kris and I loved Matt, but Jancee was hilariously ridiculous. Some of the funniest things we did happened [while] taping her segments, because she was a good sport about screwing up.

Jancee Dunn: Every year when they renewed my contract, I would say, “What, are you kidding me?” Because I never improved. But I guess they liked that I never did get smooth, because it was in keeping with the DIY aesthetic of M2. My delivery had the same unscripted, sometimes cringeworthy, Wild West feeling that the network did. It was so much fun.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=deMDT1dEFG0

Kris Kosach: And we would sort out really weird places to shoot, too, really bizarre little holes in the wall. I do not know who scouted the stuff.

Lou Stellato: The goal in the early days was to shoot in as down-and-dirty places as we could find in Manhattan. So that was fun, to find those places, to negotiate, “Can we shoot there for free, of for a very nominal fee, and we will give you credit?” Exploring the kind of low-end side of New York City. A side that doesn’t really exist anymore.

Matt Pinfield: We would end up in these basements of clubs, and these restaurants. Hat factories. Cake factories. We’d shoot in Brooklyn, we’d shoot in Queens, we’d shoot on the Lower East Side. We shot in all the boroughs and then we shot on the island.

Jancee Dunn: Stubby bars still redolent of barf from the night before. Thrift stores, we’d see mice. Or out on the street. People would yell at me.

Kris Kosach: We were at a bakery once and there were actually rats behind me, running through this kitchen, and they wouldn’t stop filming no matter what because they wanted it to be very real. So you just had to react. And they would play pranks on you on camera and make you keep going. Or a phone would be ringing while you were doing your piece, and if you were near the phone the producer would be pointing, like, “Pick it up, pick it up,” and you would actually pick up the phone and talk to some random customer.

Sheree Lunn: A lot of our locations were places that were very tight and didn’t have the greatest light. Some didn’t have the greatest air. There wasn’t really much more [room] for a beauty department, so it would always have to be, as they call it, “Run and gun.” You would do the best you could in the situation you had to work in. It was pointless trying to do something that was [like] some cover of Vogue, because it just wasn’t going to fly.

Darcy Fulmer: Now the promos and the way [the channel] looked, that was another story. It definitely had a tone. It was super homemade-looking. That was part of the charm of it, though. It didn’t look made by a giant corporation. They would just go out and film B-roll stuff and make promos and put them together.

Nigel Cox-Hagan: The format was meant to be free-form. Likewise, the branding was meant to have the [same] sense of play and that sense of exploration and surprise. I’m also a cinephile and I found a group of exploitation movies that were available [for use in M2 promos]. I was on this kick at the time: They were the mondo series. The point of the mondo series of films was to take you around the globe where they claimed to be showing you verité scenes. Things that might end up on Vice nowadays: rituals that people would find exotic and weird. Extreme expressions of sexuality or gore — just really weird stuff. And I just loved it. And for me it expressed this very weird alternate world that I wanted to create.

Jancee Dunn: In the beginning, there were so many weird promos that were completely pointless. There was one that was a pickle jar, and you heard some guy going, “Tickle my pickle, tickle my pickle.” It didn’t mean anything! You could tell it was just some promo guys having a laugh at two in the morning after some bong hits. It was crazy.

Nigel Cox-Hagan: Working with the other promo producers, we kept [restrictions] very loose. This was the opportunity for them to stretch and be creative with less boundaries than they had at MTV. Of course now, in retrospect, even the boundaries MTV had at the time look amazingly loose, but to us at that particular time, M2 was this place we could do this wild stuff, and MTV was more of the established brand.

Darcy Fulmer: I still worked at MTV at the same time. I was sitting next door to everyone who was scheduling the main channel, so it was kind of like we were out in a separate wing doing our thing for really the first year — just me and the producer and two of the VJs. We just made it on the shoestring, and everybody liked it. Everybody at [MTV] watched it all day. Because you could only get it on satellite then, it was only really in households. So to watch it in the office was a big deal.

Jancee Dunn: A lot of people for many years couldn’t even see M2! It wasn’t in New York for a couple of years, so most people didn’t know what it was.

Kris Kosach: There was no television channel for it. There was no space on the dial for it at all. We were on Satcom C3 Transponder 13 — I remember the useless stuff for some reason — but we were on this deep satellite, and the only people that really watched us were prisoners. So I got tons of fan mail from prisoners.

Jancee Dunn: A lot of the incarcerated had M2. We’d get fan letters. They were definitely carefully written, warden-sanctioned… They couldn’t get too horny or anything. If I had changes in the highlights in my hair, I’d get a flurry of letters. They were watching very closely, but I felt like, “Jeez, we can’t get on normal cable stations, but apparently the country’s prisons have full cable!” We were hearing from them all the time. We’d get requests and I’d send one out to the boys in Yuma State Prison. They’d ask for “Free Bird” or “Man in the Box.” We could have done a full hour of that.

Lou Stellato: We’d get a fan letter here and there, and we’d talk to friends and coworkers. When you’re in that kind of [bubble] — and this is true of so many cable networks — your perception is that whatever you’re working on, there’s an a bigger awareness of it than there actually is.

Jancee Dunn: Those cable companies really dug in, and were not cooperating, and were not interested. Once I accepted that it wasn’t going to be this giant phenomenon, we settled into our role as quietly subversive.

Kris Kosach: Then they would link us into MTV. They more or less made up [an M2] show on MTV proper, like a block of three or four hours.

Darcy Fulmer: [The sample hour was] a variety of everything. Play some really weird live video from the ‘70s and people are like, “What is happening?” If there was some cool new Radiohead video that we weren’t playing full time on MTV. It was a sample, so I had to kinda cram what we did in 24 hours into ten songs. It was just done to be cool, and show people what [M2] was, so that maybe they would call their cable company and ask for it.

Jancee Dunn: The great thing about M2 is that [artists] started requesting us. We did this two-hour special with U2 at the Slaughtered Lamb. It was a pub in the Village. They were all excited and in on it from the beginning. It was this really long special, where we’d sit around and talk about music. It was so fantastic. I thought, “God, U2 is excited to come here?!”

Darcy Fulmer: Dave Grohl was friends with somebody in the music department. He loved the channel and he even put a satellite dish on his tour bus. This is early Foos. So he would host, and I was like, “Do you want to play whatever you want to play?” And he was like, “Yes.” So I would get a library of videos for him and Taylor [Hawkins, drummer], and they would go through them and circle everything, and make me a list. I would program it, and then we’d make a script, and they’d come down to host. And it just became a thing.

Kris Kosach: Moby was great. I had never met him before and we became friends after that. I remember Björk being odd — go figure — and RZA was incredibly kind. And Damon Albarn wouldn’t look at anybody. He’d just keep looking at the ground. He was incredibly shy, which I remember thinking was so bizarre, that here’s this guy that [performs] in front of thousands and thousands of people, and he can’t talk to one.

Jancee Dunn: I remember Stevie Nicks was excited to come [on M2]. She was talking about other videos she’d seen on the channel. She really knew her stuff!

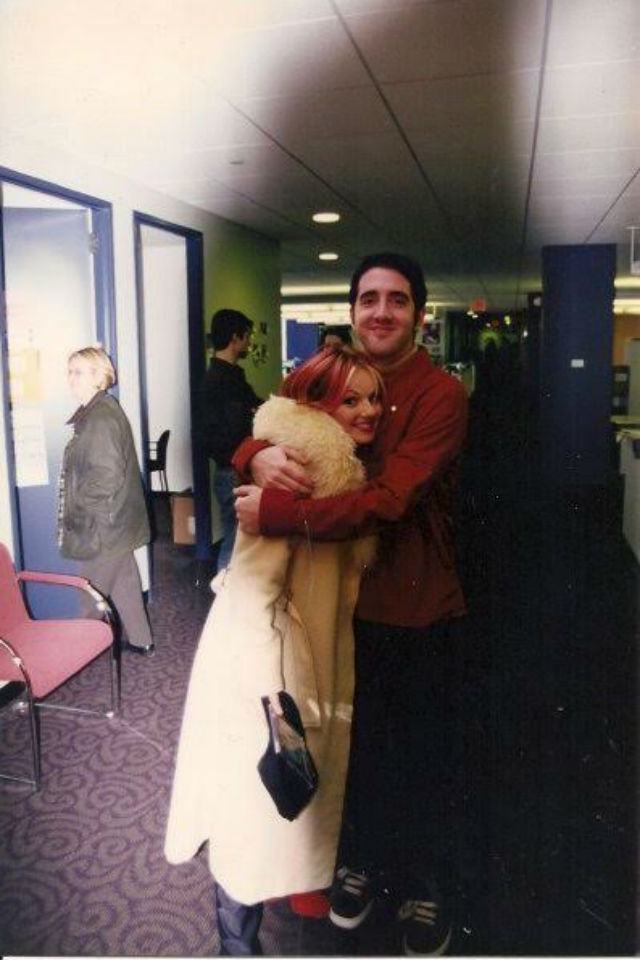

Matt Pinfield: The first-ever [U.S.] interview with the Spice Girls was there, and it was me. We did it in the conference room. They all kissed me on the head, so I’ve got lipstick everywhere.

Lou Stellato: We did their first interview right outside my office on our floor. I remember Darcy said, “The Spice Girls are coming,” and I was like, “That song [‘Wannabe’] is so ridiculous!” We were excited, and all the boys on the floor came to stare at these young, loud women who had come to visit.

Matt Pinfield: I remember giving Ginger a copy of No Doubt’s Tragic Kingdom. She had heard of it, so I gave her a copy of that. Then Scary goes, “Why don’t you grab a six-pack and come out with us later?”… There was a half hour, short-form documentary thing [the Spice Girls later released] called Spice Hour, and it has them calling me their “Spice Boy,” with a picture of them all kissing my head. It was fun. They were sweethearts, and we had a good time.

Darcy Fulmer: We played Spice Girls first on M2 because we knew about it in the music department, and the label wanted to lay it out later. They didn’t want us playing it too soon on MTV because they had a plan for it. So we said, “Well, we want it for M2.”

Kris Kosach: We broke the Spice Girls in America, and don’t hold that against us. And LeAnn Rimes was 13; she was nobody when she came on M2. She was going around the county with her parents and Patsy Cline’s manager gave her a song, and that’s where she blew up. But she was a 13-year-old kid playing fairs when we put her on the air.

Darcy Fulmer: We were super-early on EDM. We did end up putting [electronic video program] AMP on MTV, but we played Gus Gus and Prodigy and Chemical Brothers and Daft Punk way before, in 1996. It was fun for everybody at the channel to have a moment of getting to play something you like that maybe didn’t have a place on MTV.

Jancee Dunn: M2 was pretty easy and really fun. It was a small band of people, and we all joked around a lot. We were all on the same team.

Lou Stellato: I was working with family. I remember during the year TRL was kicking off, I did get a call from the mothership wanting to know if I wanted to come over and produce TRL, because the producer was leaving or something. I said, “Well, that sounds like a great idea, but you know what? I hope it’s okay, but I really like M2, and I want to stay.”

Matt Pinfield: I thought it would build itself into something big that would run alongside MTV. Whether or not I knew it was going to last forever, I certainly hoped it would. But of course, both channels have morphed into something completely different.

Lou Stellato: I’ll always remember Judy McGrath saying in the early days, “Never change.” And I remember thinking, “Oh, we’re going to change.”

Darcy Fulmer: I think the reality is, how long is that really going to last? [M2] was covering its bases [financially] as far as what we were getting from a couple of promotional partners, but it definitely wasn’t earning money. So you can’t expect something like that to continue.

Lou Stellato: I knew in order for us to survive we would have to have commercials. The only reason you have commercials is because you’re starting to have viewers. Once you have viewers, you have to start paying attention to that. So it’s a double-edged sword, because with success comes great limitation, and I knew that that would happen.

Nigel Cox-Hagan: The commercials were starting to happen. First of all, there was a decision that [M2] had to be made into MTV2 — I was around when that happened. Unsurprisingly, there were a lot of rational reasons to make that transition, but when they really decided that it could no longer be just a music channel or a heavily music-themed channel, I had long departed.

Darcy Fulmer: Towards the end, when they decided to start doing other stuff with the channel and making it MTV2, I was out. Once it wasn’t this pure 24-hour music video thing, I moved into [the online department]. They had let Andy Schuon go the year before, and a lot of things had changed.

Andy Schuon: The one thing that we always have said as a general programming philosophy is it’s easier to tighten things up than to loosen them. If you start out from a broad place, it’s much easier to take things out than to add them. So over time, it would be easier to hone or focus the direction of it, which is kind of what happened at first [with M2], I believe. By 1998, I left, so the channel hadn’t been on the air very long nor had it been very widely distributed. I really didn’t have a chance to see the transition to MTV2 from M2.

Kris Kosach: MTV was doing massive layoffs [in 1997] and every week I saw people getting laid off, and I remember saying to them, “Should I be worried that my contract is expiring?” And everyone’s like, “No! They love you, you’re great.” And then my contract expired and I’m like, “Hello?” And they’re like, “We don’t have any money. Sorry.”

Jancee Dunn: The writing was on the wall when they started re-trenching [in the early ‘00s]. We definitely wanted to appeal to the 14-year-old guy demographic. That’s when it was time for me to go. At that point, I think I was the oldest female VJ in the history of Viacom. I left the channel when I was 35… I’m like Grandma Moses. Someone like Kurt Loder, I think he was in his 60s [at MTV], but that would not be happening if he was a female. So yeah, I’m proud of that.

Nigel Cox-Hagan: Maybe in retrospect I’m surprised [about all the changes], but I’m a little more jaded now. At the time, you think, “This is the way the world should be.” Because it is the way the world should be. This was the kind of stuff I wanted to watch. I don’t actually think it was niche — well, I guess it was niche, we just didn’t have the technology to understand how to reach and really galvanize those individual niches. So I think it was much more popular than we could know.

Kris Kosach: They told us from the beginning, “Look, eventually you guys are gonna have to be like the other networks.” They didn’t say we weren’t gonna be playing music anymore, but they said eventually they’re gonna start looking at us a little bit closer, and looking at ratings, and we’re gonna have to get creative when it comes down to that. But for the time being, no commercials, let’s have fun. So yeah, it was sad [when the changes happened], but it was like graduating from high school. You know it’s going to come to an end, and it’s going to be sad, but it is what it is.

Matt Pinfield: It felt kind of like a party every day. Not that we were getting f**ked up, by any means. It was just fun. Whenever you’re involved in something musically creative, from the very get-go, there’s definitely an excitement that anything can happen. And that’s where it was for me, at that period of time.

Kris Kosach: I can honestly say, I swear to you, there was nothing sour or sad or weird about it. You would go [to the office] on a Sunday night to do some research and there would be other people there working, just because we loved it so much.

Jancee Dunn: It really wasn’t like working. And at the end of it, I had the apartment [that M2 helped pay for], and a lot of good memories because it was absolutely super-fun. This isn’t nostalgia, saying it’s fun when it wasn’t at the time. It was just great.

Kris Kosach: I think that it’s a testament to M2 that a lot of people have stayed in touch on Facebook. We’re all still friends 20 years later.

Matt Pinfield: I meet people that tell me that they loved the channel and they would sit at home after school, whether they were in college or in high school or even 13, 14, 15, in that period of puberty. They would come home and just sit in front of the TV, like they would with MTV, and watch the channel and discover new music.

Andy Schuon: It definitely was one of those things where starting with a blank piece of paper, thinking about the values, about what the voice of a brand was going to be, building it brick by brick… doing it with M2 became a little bit of a boilerplate or a template for me doing that many more times in the past 20 years. I really loved the process, intellectually and creatively, of building a media brand, and have done it many times since then, so I would say I personally got a lot out of the M2 experience.

Darcy Fulmer: It would be interesting if you put it on MTV for two days [now] and see what everyone thought.

Lou Stellato: With the dawning of YouTube, there’s really no need for [M2 today]. Everything is very viewer-controlled now and the element of surprise is not appreciated, and I understand that. It’s just part of progress.

Nigel Cox-Hagan: I know videos have made somewhat of a comeback as an experience, but I don’t know that a linear [music-television] model will ever work again. Whereas [in the past] people would trust MTV networks and that brand to be the influencer, to be the guide, now that kind of influence is atomized through podcasts and all sorts of different things you can find online. So I think it still exists, it just exists in a different form, and the audience has much more of an ability to participate and create those experiences for themselves now.

Matt Pinfield: People have so many places to go to discover music today, between YouTube, and streaming services, and reading magazines, digitally or in print, whatever it happens to be. I think [M2] was definitely a space in time, and I’m glad I was a big part of it, but things are very different today. Whenever anybody comes up to me and says, “Man, I wish it were like it used to be,” I’m like, “But it could never be. It’s a different time.”

Kris Kosach: I think there absolutely, desperately needs to be something more like M2 all over again. The idea of MTV has completely changed and so now [music] is all on-demand, like the Pandora idea of life: “If you like this, you’ll like that!” What you get at the end of the day of playing bands that sound like the Pixies, as much as I love the Pixies, [is that] I’m not going to be turned on to anything that’s completely different. I wouldn’t be a fan of Reverend Horton Heat if M2 hadn’t played it, or N.W.A. Where would have a little white girl listened to N.W.A, before? So I think there absolutely needs to be one. And I would give my front teeth to be a part of it.

Matt Pinfield will release All These Things That I’ve Done, a memoir that partly covers the M2 years, this September via Simon & Schuster.