“This is going to hurt your ears a bit,” Gonjasufi announces over the mic as he cues up a gnarled synth riff on his Roland sampler.

It’s just after 10 p.m. on a Saturday in July, and a diverse crowd of hip-hop heads is packed into the lobby of the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. Low End Theory — one of L.A.’s most popular club nights, epicenter for Southern California’s special brand of head-nodding, post-Dilla beat music — is putting on its third-annual music festival, with a stacked lineup of local beatmakers and MCs appearing throughout the day and Wu-Tang heavies Raekwon and Ghostface Killah set to headline later in the night.

The summer heat has finally cooled off, and marijuana smoke occasionally wafts in from the patio outside. Eprom, a West Coast beatmaker, has just finished off his set with a crowd-pleasing dose of wobble bass, and everybody’s having a good time.

Now it’s Gonjasufi’s turn.

“You ready?” the 38-year-old singer and yogi yells, to scattered cheers from the audience.

“You motherf**kers ready???”

More cheers.

“Don’t be afraid.”

Gonjasufi might just be the wisest practitioner of vocal esoterica in electronic music. When he first emerged in the public eye, in 2010, with his critically lauded debut on Warp Records, A Sufi and a Killer, there was nobody else quite like him. Over shamanistic psych beats from L.A. luminaries Flying Lotus, the Gaslamp Killer, and Mainframe, he crept into your subconscious with cryptic lines of poetry and a throaty rasp of a voice. By turns mournful and melodic, giddy and crazed, he sounded familiar and alien at the same time — a descendent of Parliament-Funkadelic and Portishead from some bizarro planet where everything’s infrared.

When the album came out, Low End Theory was just hitting a peak, and as his beat-scene contemporaries went on to book spots on international festival stages and develop crossover appeal while collaborating with heavyweights like Kendrick Lamar, Gonjasufi earned some well-deserved hype of his own. He got airplay from the taste-making BBC radio DJ Mary Anne Hobbs. Jay Z reworked his song “Nikels and Dimes” for his 2013 album, Magna Carta Holy Grail.

Sufi’s been quieter in recent years. But now he’s back, screeching off even further down his own path. His new album, Callus — out this month on Warp Records — is an unapologetic inferno of inner torment and rage, a beat-oriented record where the songs evoke harsh moods and strange beauty while verging on internal collapse. Gonjasufi’s voice is more unhinged than ever as he howls about organized religion, racism, and hypocrisy. Where they once offered blunted relief, the drums now have been EQ’d horribly out of shape, banging against a backdrop of droning synths, decayed Game Boy textures, and crude guitar licks.

Callus does have more straightforward moments, like the fist-pumping synth jam “Krishna Punk” and the bittersweet, almost Depeche Mode-ian “Vinaigrette.” But even those tracks ooze with a queasy dissonance that might leave some listeners curled up in the fetal position.

It’s the most twisted electronic album to come out so far this year: the rawest expressions of a man who’s endured drug addiction, discrimination, voices inside his head, and 100-plus degree Bikram yoga sessions. Gonjasufi’s body is battered. His brain, as he puts it several hours before the show at Low End Theory Festival, is “all f**king f**ked up.” He sympathizes with other people’s pain. Now it seems he’s taking on the role of a spiritual guide, bringing us down deep into the gutter so that we might elevate our understanding of the world.

“He’s like a suffering Rasta who just wants to make the world a better place. But he’s so angry, because he’s also a hip-hop ’hood motherf**ker who’s been through hell,” says William Bensussen, a.k.a. DJ/producer the Gaslamp Killer, a resident at Low End Theory and a longtime friend and collaborator of Sufi’s. “Everything he has to say is truth. And it’s harsh truth, but it’s truth. When you speak the truth, even if it’s ugly, people need to hear it.”

On the day of the Low End Theory Festival, the weather in L.A. is brutal. Temperatures are reaching into the upper 90s and half the sky is blotted out by smoke and ash — signs of a brush-fire tearing through the Santa Clarita Valley up north.

Gonjasufi, who was born Sumach Valentine and goes by Sumach Ecks, doesn’t seem to mind. Around 3 p.m., he rolls into the city from his home in Joshua Tree, with his pregnant wife and two of his five kids in tow. Two Warp Records staffers are outside the Shrine to greet him, and as he takes a seat beneath a tree next to a plot of grass for an interview, they run off and return bearing bottles of ice-cold water from a nearby CVS pharmacy.

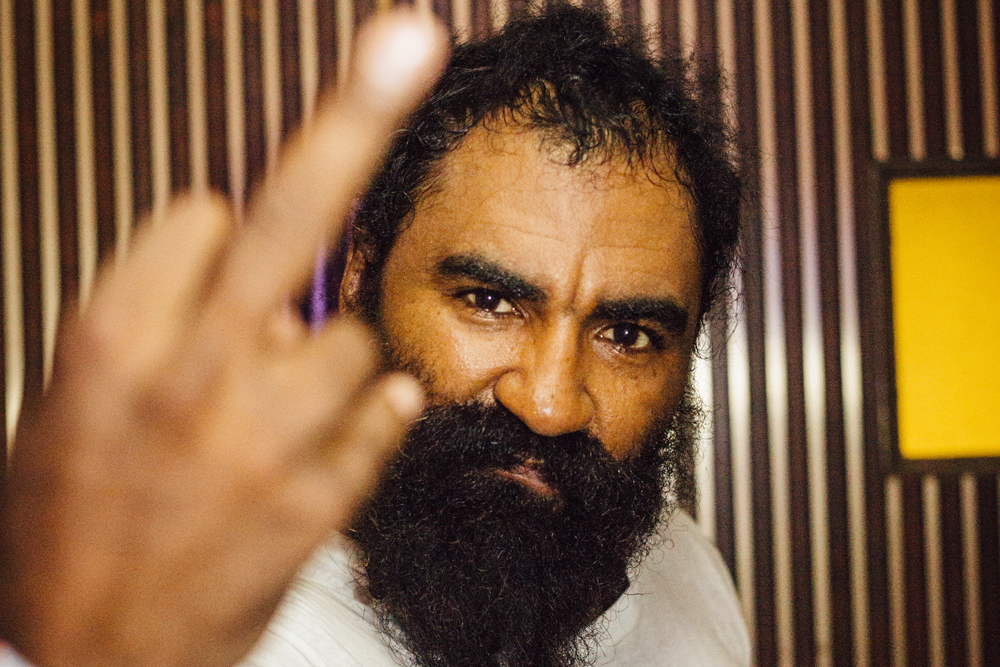

Dressed for a journey, Ecks is wearing a T-shirt and athletic shorts. He’s got no socks on and the soles of his beaten-up Puma running shoes are worn smooth. He’s lived under the hot sun for years, first in Las Vegas and now in Joshua Tree. His skin looks tough and leathery, and, like the smoke-choked skies above, his face is obscured — emotions unreadable behind black sunglasses, a knit beanie, and a giant, dreadlocked beard.

When he takes off his shades, his eyes glimmer with intensity. As he speaks, his expressive voice modulates from a deep gruffness to a softer, higher tone. Clearly he has a vulnerable side.

“I’m a f**ked-up dude, man,” he says. “My head is full of doubt. One-hundred percent doubt. My heart — complete faith. So I just go into that s**t. And I’m not afraid to pump from my heart, man. I tell motherf**kers I love ’em, dawg, all the time. Every time I talk to my boys or anybody, motherf**kers I just met — ‘I love you, bro!’ I smile at ’em. Just f**king love, homie. What would you rather me do? Beat the s**t out of you? That’s an option, but that’s not what I wanna do.”

According to Ecks, he wasn’t always so intense. Growing up in the South Bay suburbs of San Diego, he spent his middle-school years getting good grades while nurturing dreams of one day playing professional baseball. He’s got two siblings, a brother and a sister; his father is a Superior Court judge who presides over criminal cases in San Diego’s downtown courthouse, and his mother is a teacher who works with special-needs kids.

But his life took a different turn in high school. He was mesmerized by Tupac Shakur’s role as the volatile young gangster Roland Bishop in the 1992 film Juice. His first time smoking weed and listening to Bob Marley was a downright spiritual awakening. When he got into a car wreck that left him with a broken femur and a titanium rod in his leg, his athletic pursuits were over and his passions swayed completely toward music.

“When the accident happened, that was just like the nail in the coffin — ‘Okay, just go into the art, G,’” he recalls.

Ecks found his new calling at the Underground Improv, an open mic put on every Sunday night from 1995 to 1997 in the Encanto neighborhood of southeastern San Diego — one of the centers of the city’s black community. The event was hosted by Orko the Sycotik Alien, a rapper, beatmaker, and dancer who was a only a couple of years older than Ecks, but who’d grown up in some of the city’s earliest hip-hop crews and was now selling cassettes and CDs of his albums on the streets and laying the groundwork for the local scene.

Orko (who now goes by Orko Eloheim) rapped at extreme velocity, advancing Afrofuturist philosophies and psychedelic mental travels. He dismissed mass media as “tel lie vision,” subverted inner-city stereotypes by rapping about the “rhyme rate” instead of the “crime rate,” and made the grimiest beats possible on an outdated Ensoniq Mirage sampler keyboard. According to Ecks and the Gaslamp Killer, during open mics Orko would snatch the mic right out of your hand if you were delivering a subpar performance. Touring hip-hop artists who came through town ran the risk of getting their stages hijacked by Orko and his crew, the Masters of the Universe.

Ecks — then rapping under the name Sumach — joined up with the Universe and sought to find his voice. In his appearances on albums like Orko’s Crop Formations from 1995, he sounds nothing like he does today. (“My balls was still in my throat,” Ecks says.) But Orko kept bringing him in, teaching him to be fearless and uncompromising. They became close friends and kept collaborating for over a decade, and today Orko says he learned a lot from Ecks as well.

“We were lucky to have each other,” Orko says, speaking by phone from St. Paul, Minnesota, where he now lives. “As much as he learned from me in the rap game — rapping and singing and making beats and stuff — that’s how much I learned from him in being myself, in spirituality. If you link up with the right people, it just enhances your energy, your chi, your spiritual. You know what I mean? It turns you up a notch. That’s how it was with Sumach.”

While Ecks came into his own in San Diego, he also wrangled with inner demons. In the late ’90s, he dropped out of college at San Diego State University and moved to the San Francisco Bay Area to watch over his little brother and take care of his dying grandfather. The Bay is one of the great meccas of West Coast hip-hop, and Ecks says he spent two years in Oakland and Berkeley, collecting crates of vinyl while learning to make beats on the Akai MPC drum machine. But when he returned to San Diego, the experience was a culture shock. He was being profiled for his beard and dreads. He got arrested at the beach. Over the years he says he’s struggled with hearing voices inside his head, and as he was plagued by doubts, he descended into a haze of pill-popping and drug addiction.

“I started doubting myself, so I started f**king getting into dope and started doing a lot of drugs and popping roaches and painkillers and s**t,” he recalls. “There’s years that I don’t remember. From, like 22, I was pilled-up every day, man. I was f**ked up. Everybody that knows me remembers that.”

Eventually he pulled himself out of it, but the experience left a mark that would surface in his music. In the second track off of Jungl Bulit — a rap album he self-released under the name Sumach in 2007 — he raps about this time period in harrowing detail. The beat tumbles like a piano going down a staircase as he raps: “Talking to myself / Having schizophrenic moments / Sitting on the corners / Sipping on Coronas / So high I felt like I was always in a coma.” His voice is buried in a tomb of sub-bass, but then out of the murk comes that throaty, haunting rasp, the singing style that would later make him famous, and he delivers a refrain that would define his ethos as an artist: “I’m West Coast / I’m gutter.”

These days, Ecks relishes in the support of his family. In addition to their five kids, his wife (who appears on some of his songs as singer Blakhalemary) is expecting a baby boy in November. Living in Joshua Tree — a desert region in Southern California beloved by artists for its epic rock formations and gnarled titular trees — gives him space and quiet. He sweats out his demons and toxins through yoga, but while he’s benefited a lot from the practice, he’s also vexed by it — pointing out that a lot of people seem to be into it for superficial reasons.

“You get people who just practice yoga, they put their head in their ass or they’re pulling their head out their ass or they’re staying out of their head,” Ecks says. “And for me, there’s other limbs of the yoga other than flexibility in your body. Can you apply what you learned in that room outside?”

The years after the release of A Sufi and a Killer have given Ecks great opportunities, but he’s also struggled with success. After a tour in support of the album, he says he got ripped of by his booking agency and ended up broke. The pressures of being in the public eye sent him back into hard drugs, and he says he finished his 2012 follow-up, MU.ZZ.LE, in a month-long coke binge. Around this time, his toxic intake led to a near-fatal overdose. For a couple of days he was throwing up repeatedly while a massive pulse pounded through his head. He ended up kicking the hard stuff, but his body’s never been the same.

“I wanna see my grandchildren, G. I need to stick around, dawg. If I do that s**t again, I’ll die. My f**king heart can’t take this,” he says. “I’m scarred up for life, literally. There’s parts of my body that hair won’t even grow because it’s scarred up.”

Gonjasufi seems to have mixed feelings about his public stature. He once deleted his Instagram because he felt like he was showing off, and he refers to his Twitter in his bio as a “parody account,” seemingly uneager to boost his following. But he’s proud of his achievements, and when Jay Z sampled him on Magna Carta Holy Grail, it was a triumph not just for him but for the entire San Diego underground he grew up in.

Callus, as tortured as it sounds, is actually a labor of love. It features a cast of close collaborators, including friends from San Diego’s hip-hop scene. Pearl Thompson, an original member of the Cure, contributes guitar parts on three tracks. Gonjasufi also taught himself the six-string while working on the album, eager to expand as a musician and prove that he’s not just some “karaoke” artist singing over somebody else’s beats.

At the Shrine for his Low End Theory festival set, Gonjasufi terrorizes the audience like only he can. Throughout the 30-minute set, some people in the audience take off. Others just stand there, dumbfounded. Sufi is mashing the orange buttons on his sampler, twisting knobs, DJ’ing tracks off of Callus. The album highlight “Afrikan Spaceship” comes on, and the beat is a merciless burst of low-bitrate feedback and noise. The lyrics are like something you’d see scrawled on a wall in a post-apocalyptic war zone: “Don’t tell me what to believe in / ’Cause we don’t believe in you!” Sufi nods his head aggressively to the beat. He’s lost in it, feeling it, poised perfectly between love and doubt.

“My pain is self-induced, because I care about humanity and I care about the state of the world, and when I go out I try to absorb people’s f**king pain,” he said earlier in the day, the sun shining down on this man who’s been through so much.

“I feel like a bodhisattva. Imagine if when you die, you go to heaven and God says, ‘Come on, son.’ And you say, ‘Naw, I need to bring everybody with me.’ And He’s all, ‘Well, they can’t come,’” he adds. “‘Well, then I’m going back down. Until they can come, I don’t wanna go.’ That’s kind of what my mission is now.”