In an issue of his comic-book series The Sandman, Neil Gaiman tells an old tale focused on the fantastic ancient city of Baghdad. It was a “city above cities,” where wealth was endless, the scholars were the best of the best, and the architecture was unmatched. The city was a miracle, with magic carpets and s**t. But Baghdad’s caliph, Harun al-Rashid, constantly brooded while surveying his land; he knew Baghdad’s perfection was temporary because all things prosperous eventually decline.

It’s a fatalistic idea that’s proven itself true countless times throughout time: Rome fell, the Summer of Love died as the Vietnam War waged on, and Dipset broke up. All things man-made — cities, relationships, cultural movements — must pass. The falling Towers marked the point where buddies Tunde Adebimpe and David Sitek transformed TV on the Radio from a half-serious band into an ambitious creative venture with a sense of purpose. And when a promising scene rose in the wake of 9/11, they stood at terminus gazing skyward for meaning. In doing so, they became New York City’s spiritual equivalent to Radiohead, another art-rock act who stood apart from their more accessible contemporaries, preferring to examine and worry over the State of Things.

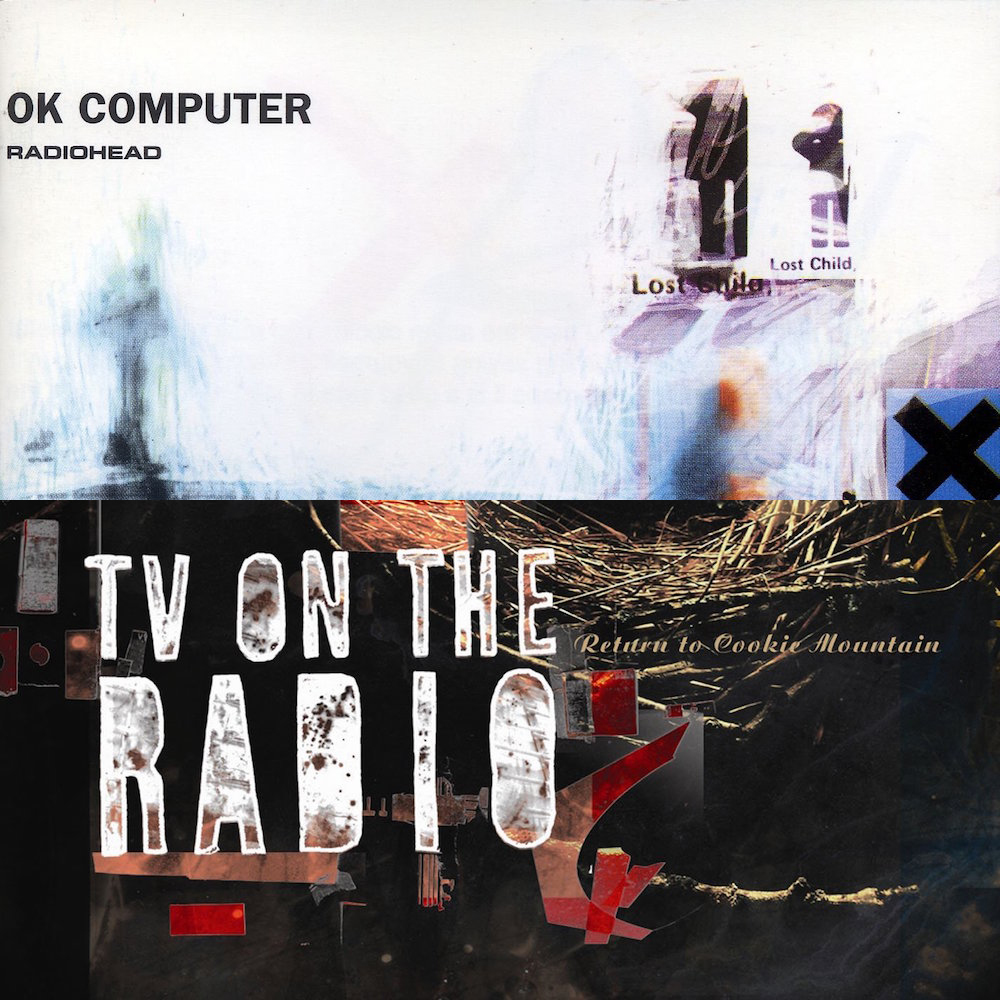

Return to Cookie Mountain, which celebrates its tenth anniversary today, and 1997’s OK Computer are the jewels within their respective bands’ catalogs. They illustrate desire against a backdrop of societal chaos, compressing emotive songcraft and guitar debris into diamonds. They’re both exhausting listens in which even the moments of respite are enveloped within dying light: Cookie Mountain‘s David Bowie-featuring “Province” describes love as an iridescent weapon instead of a joy in itself, and it takes an airplane crash for Radiohead to lighten up a bit. But Return to Cookie Mountain and OK Computer aren’t just linked by their dalliances with dread. They effectively bookmarked the end of their separate eras: the New York early-’00s rock revival that wrapped itself in retro garments, and the ’90s Britpop that did the same to greater commercial dominance.

Radiohead and TV on the Radio placed themselves parallel to their different scenes, rather than as products of them. Like their predecessors, the stars of New York’s turn-of-the-century revivalism blended sonic abrasion with disaffected cool. Yeah Yeah Yeahs sharpened their style by drawing from Sonic Youth’s noise and the capriciousness of Big Apple transplant PJ Harvey; Lou Reed’s poetic ramblings and the Ramones’ leather jackets resurfaced as part of the Strokes’ chic; and you weren’t a fool to hope that Interpol would eventually outgrow their Factory Records infatuation. Britpop’s touchstones were less varied, blending the Smiths’ dreamy romanticism, hysteria-inducing ‘60s pop, and Bowie-era glam.

Part of what helped distinguish Radiohead and TV on the Radio was how far-flung their influences seemed, especially when compared to their peers. The British quintet pulled from the dense dynamics of Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew, DJ Shadow’s trip-hop time paradox, and Queen’s operatic grandeur (“Paranoid Android” was the Oxford clan’s own “Bohemian Rhapsody”). TV on the Radio were a peculiar amalgamation of folk, gospel, doo-wop, and post-punk. (They were also both inspired by the hugely influential Pixies; you can trace the carnality of “Wolf Like Me” to Black Francis & Co.’s late-’80s hedonistic surrealism.) The two groups were music nerds disguised as rock stars — the bookish, secular alternatives to the major-key chest-beating peddled by other artists.

It wasn’t as if these bands arrived fully formed. By 2003, TV on the Radio already had remarkable achievements in the Young Liars EP’s title track and “Staring at the Sun,” and Radiohead had commercial and critical triumphs with “Creep” and The Bends. But OK Computer and Return to Cookie Mountain represent the moments when TVOTR and Radiohead first felt truly singular. Their influences had coalesced into works with their own enigmatic atmospheres. As a duo, TVOTR frontman Tunde Adebimpe and guitarist Kyp Malone were frayed and contemplative, where other NYC stars survived on angular thrills. Thom Yorke’s voice sneered anxiously as Oasis and Blur raked in cash singing the dreams and comforting the nightmares of the British working and middle class.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=sPLEbAVjiLA

And money can destroy a movement on any continent. More of a commercial construct than an actual genre, Britpop was inherently a doomed phenomenon. Labels realized that, shockingly, investing in Oasis and Suede copycats didn’t net the same returns as signing the actual Oasis and Suede. By the time the Spice Girls’ takeover began in 1996, many Britpop acts morphed from larger-than-life figures to alcoholic sods. A few years later in the States, the Strokes lost their edge not too long after James Murphy stressed about losing his. Some of the era’s best — the Walkmen, the Hold Steady, Yeah Yeah Yeahs — were still producing strong work in the middle of the 21st century’s first decade, but New York fell off as an incubator of fresh, noteworthy talent. That’s what happens when a creative community gets hyped and something that once grew organically turns into a pose that wannabes and executives start striking.

We’ve all heard the next few complaints: Indie rock in NYC became a parody of itself, rents skyrocketed, chain businesses made sure all of the grit was sanitized, Williamsburg and the Lower East Side became playgrounds for yuppies and fortuitous college students. Those weren’t extinction-level events, though; Vampire Weekend and LCD Soundsystem carried the torch for late-2000s New York, synthesizing their own sets of idiosyncratic references. But Ezra Koenig’s Ivy-League grin and Interpol frontman Paul Banks’ sloppy bangs aren’t of the same lineage — they’re bonded by location, not aesthetic. The city’s early-’00s wave died by the time TV on the Radio rolled out Return to Cookie Mountain as their major-label debut in 2006. About a decade earlier, OK Computer made Britpop seem too ’90s before the ’90s were even over.

That tale about Baghdad ends in tragedy. The caliph asks the Lord of Dreams to take his city and promise that it will never falter. The Lord of Dreams agrees and eternally preserves its glory in his domain. Thus, the perfect city literally becomes a dream; it’s only a fantasy of the people inhabiting the now war-torn Baghdad.

Return to Cookie Mountain and OK Computer were both turning points — they’re the albums that captured the changing of the guard, when the scenes TVOTR and Radiohead rose above began turning into idyllic memories. In New York, the homegrown DIY spirit died for the sake of cushy condos. I assume Brexit and Adele’s smothering omnipotence could make a British music fan recall the days of Britpop’s hubris with renewed fondness. The world is now vastly different from what it was in 1997, yet Radiohead proved this year with A Moon Shaped Pool that they’re still a vital band. And Return to Cookie Mountain is as engrossing as it was ten years ago, which is longer than Williamsburg’s Stay Gold — the studio it was recorded in — lasted. A new J. Crew opened up in the space in 2014, replacing the birthplace of a gorgeously damaged album and filling it with overpriced sweaters.