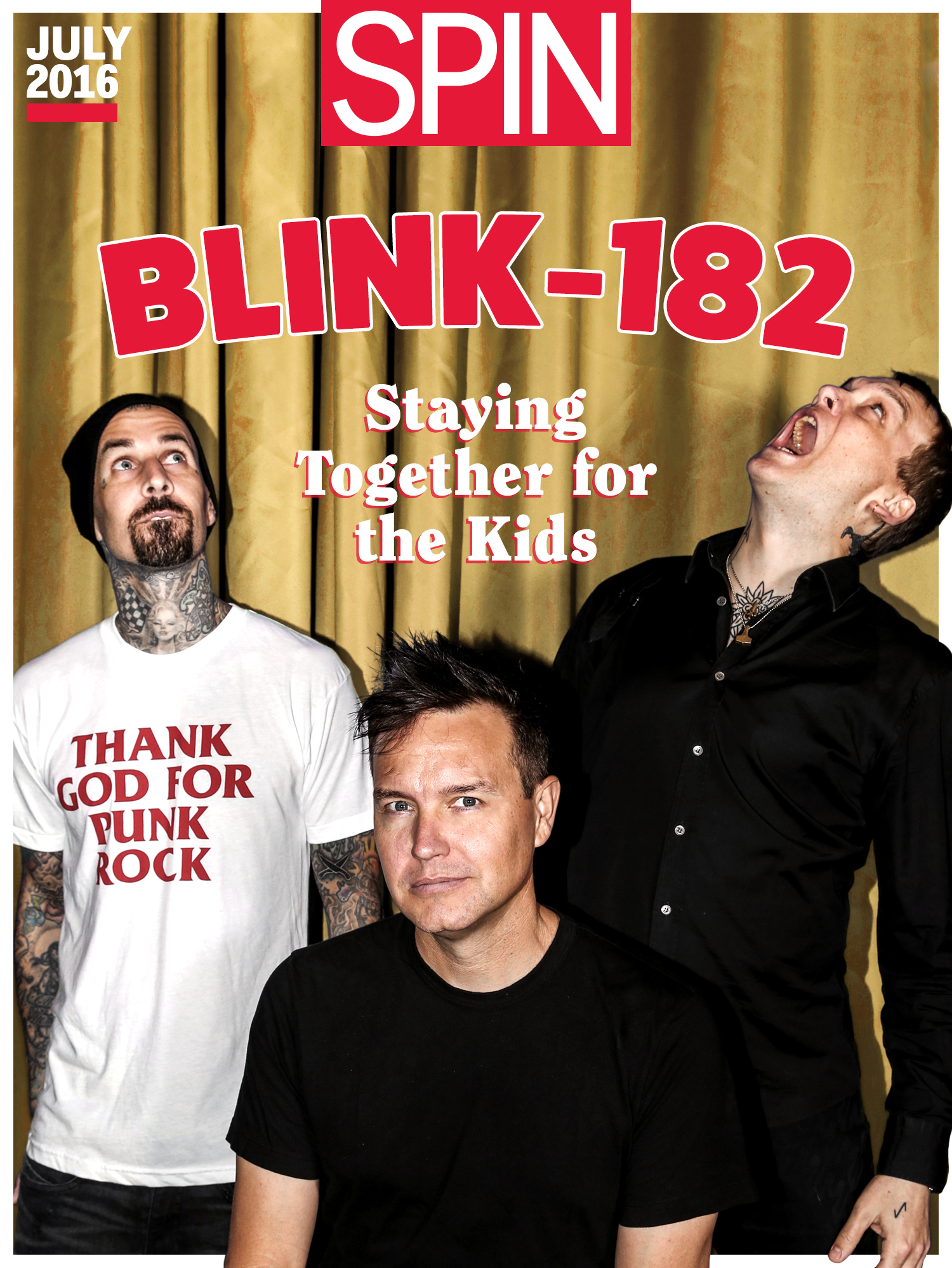

“Show me images of Travis Barker,” Mark Hoppus tells Siri as he prepares to pose for a SPIN photo shoot. “You’ll need to unlock your iPhone first,” comes the automated reply. Undeterred, Hoppus finally locates a batch of pictures and turns to show the tatted-up, 40-year-old drummer, who arrives at YouTube’s studios in Manhattan almost an hour after his bandmates to discuss Blink-182‘s seventh studio album, California. “Lots of you in this red hat,” Hoppus says, smirking, before changing his request to include the group’s newest recruit, Alkaline Trio guitarist Matt Skiba. Blink’s sole remaining original member, Hoppus might be well into middle-age now, having traded Atticus apparel for a shiny Apple Watch (he also shows off a new and very responsible-looking leather toiletries kit), but he still finds time to needle his buddies like a fidgety teen.

A little light-hearted heckling is hardly unusual for the 44-year-old singer-bassist, who once ran nude through the streets of Los Angeles and helped write modern pop-punk cornerstones like 1997’s puerile Dude Ranch, 1999’s platinum-selling breakthrough Enema of the State, and its even glossier follow-up, 2001’s innuendo-driven Take Off Your Pants and Jacket. Still, it’s been 24 years since the West Coast pranksters first came together, a stretch of time you’d think would result in some serious personal growth — or at least fewer poop jokes. And that’s what happened, to a certain extent: The band’s gloomy, untitled 2003 album and 2011’s grandiloquent Neighborhoods are markedly more stone-faced than Blink’s earlier LPs, trading toilet-humor trifles like Take Off‘s self-explanatory “F**k a Dog” for yawping odes to deteriorating romance (“Stockholm Syndrome”) and suicide fantasies (“After Midnight”).

In between those two sobering full-lengths, the band went on an “indefinite hiatus,” with former Blink singer-guitarist Tom DeLonge citing creative differences and a wish to focus on his family life. (“It was getting to a point where it was a lot more than I wanted to commit to,” he told Rolling Stone at the time.) DeLonge, Hoppus, and Barker appeared to reconcile their differences when they reunited in 2009 and began working on Neighborhoods, but history looks to have repeated itself: DeLonge parted ways with the band for the second time last year, again expressing a need to explore other avenues, like his overblown Angels & Airwaves project (and, apparently, UFOs). This latest — and much-publicized — lineup switch has catalyzed a rebirth of sorts, and with it, a lightened mood.

Now that Skiba, 40, has replaced DeLonge, the guys agonize a little less about shooting stars burning holes in your hand and drowning in wishing wells. They’ve even thrown a few more vintage-Blink lyrical gags on the just-released California (“I wanna see some naked dudes / That’s why I built this pool,” Hoppus blares on the 14-second “Built This Pool”). “[The humor] was a reflection of what we were doing in the studio.” he reasons. “We were having fun and we were making jokes.” Even California‘s weightier themes — anxiety-born insomnia on “Rabbit Hole,” mulling over years long past on “Bored to Death” — appear jollier, buoyed by airtight harmonies and Skiba’s SoCal-minted chords.

Below, in a conversation that has been edited and condensed for clarity, Hoppus, Skiba, and Barker expand on how Blink has evolved over the past quarter-century, what the Alkaline Trio guitarist has brought to the band’s chemistry, DeLonge’s sudden departure, and finding their way back to funny. You know, all the small things.

What did you originally want to accomplish when you started Blink-182?

Mark Hoppus: There was a club in San Diego called Soma, where we used to go see punk-rock bands play all the time. There was an upstairs which probably held about 1,000 people, and there was a downstairs that probably held 150 people. If you could get 50 people to say that they were there to see your band in the basement, you would get to open a show for the upstairs venue. So that was our goal, to make it to the upstairs. That was cool because it meant that people who weren’t our immediate friends were paying to come see the show.

What did Travis add to the band when he joined in 1998?

Hoppus: Travis was then — and still is — the X-factor in Blink-182. He is the great unknown that takes a song idea to a totally new place. The beats that he brings in and the ideas that he has for arrangements really make Blink songs something special.

Travis, what’s your personal favorite memory of playing in Blink-182?

Travis Barker: When I first joined the band, it was awesome. I was touring with the Aquabats and the Vandals at the time. I was like a drum-whore, really. Anybody who would take me, I would play with. And they needed a drummer, and I just started filling in and playing shows with them. It was so fun because I was learning 21 songs within, like, 45 minutes before a show. It was so spontaneous, and I had to adapt really quick.

Once I was in the band, going to Iraq was really touching. It was kind of emo for me, going and meeting soldiers who were, like, 19 and hadn’t even met their kids… Or dealing with depression. We played on a boat with a bunch of soldiers — it was really cool. We had this one kid come and play drums — but just being with those soldiers and traveling with them in helicopters and people with M-16s… It was an eye-opener.

Your first album with Travis, Enema of the State, was your breakthrough record. What do you think it was about that record that really connected with people?

Hoppus: I think that we were really hitting our stride, songwriting-wise. I think that breaking into the mainstream — it was just the right cycle of music for us. People were kind of over the boy-band, pop-princess, manufactured sensibility, and were excited for guitars and angst and energy and enthusiasm, which is our thing.

I think Enema of the State and its follow-up, Take Off Your Pants and Jacket, have undergone a critical reevaluation between then and now, likely because the fans that grew up with your music are now the critics who review your records. Do you agree with that?

Hoppus: I think people take Blink more seriously now than they did before. And it’s largely our fault because we called [our records] Enema of the State and Take Off Your Pants and Jacket and had videos of us running around naked through L.A. and did stupid jokes onstage and things like that.

We were always kind of the underdogs, especially critically. People wrote us off as this joke band. But the people who listened to Blink knew that we were silly and whatever, but we wrote songs about divorce and suicide and depression. We did have joke songs, but we had songs like “Adam’s Song” or “Stay Together for the Kids.” Those kids that were listening to Blink are now the ones that control all these outlets that used to just write us off.

I still feel like we’re the underdogs, but I feel like people respect us now. People might not like our band or love our music, but I think people respect the fact that we’ve been doing this for 25 years and are still doing it and still able to play three giant New York City shows and have people come out.

When you play your earlier stuff, how do you reconnect with songs like “What’s My Age Again?” and “All the Small Things”? Do you still feel as close to them now as when you wrote them?

Hoppus: Totally, yeah. Every one of those old songs is like a tattoo or a scrapbook or an old photograph. There are just songs that define certain moments in your life. Everyone has a song that got them through a bad breakup or they put on and it made them feel like they wanted to go out and kick the world’s ass with their friends on a weekend. Those songs still feel like that to me. When I play “The Rock Show,” I still get excited in the same way we did when we first wrote that song.

Barker: [Enema of the State] is kind of like a tattoo, like a moment in time, but it aged well. It’s not like one that you’re looking at like, “Aw, God, I gotta get that s**t removed.” It’s something we’re proud of. For me, I had just come in the band. I was a lot like Matt, I was very new at that point. I was just touring with the band, and it was time to make an album and be a part of the writing process, and being able to have my input on tempos and different rhythms and stuff was really fun and exciting.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”201344″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2016/07/blink-182-california-new-album-cover-story-2-300×133.jpg”]

Take Off Your Pants and Jacket was your last juvenile-humor album. Was it an intentional move to taper off the jokes after Take Off?

Hoppus: No. I mean, I remember when we were writing [Take Off] and writing jokes, I said, “I want to take this as far as we can go.” We had some joke stuff before, but I wanted to really push it on that one. Then when we did the untitled record, we just didn’t feel like putting joke stuff on it, so we didn’t. It wasn’t really a deliberation or a real introspective [thing like,] “Are we going to joke on this one, are we not going to joke on this one?” We just didn’t feel like it on the untitled one, so we didn’t.

When the untitled record came out, did its different direction give you the sense that you guys had found new life as a band?

Hoppus: Yeah. We worked very hard on that record to do something different and that we were proud of and [to] try a bunch of different ideas. We worked on it for a year, and pulled every song apart, down to its foundations, in different arrangements and different styles. It was like this gigantic musical laboratory that we were going to every day. I love that record, I think that’s one of the high watermarks of us as a band.

Part of your long history has, unfortunately, included tensions with your Blink co-founder, Tom. How far back does that divide go? As far back as Box Car Racer?

Hoppus: It was weird for a number of months [when Tom and Travis started Box Car Racer in 2001], and I talked to Tom about it, and we hashed it out back then. It’s never been an issue since before the untitled record. Everything was fine after that. This time, Tom kind of quit the same way he did the first time [in 2005], where he just had his manager contact us and say that he didn’t want us to contact him, and that he wasn’t going to do Blink anymore.

“We were always the butt of our own jokes,” Hoppus says. “I think that people saw that we weren’t really making fun of anybody except ourselves.”

Tom has repeatedly denied that he “quit” the band. Why would he say he didn’t formally quit?

Hoppus: I don’t know why he says that. I mean, if he still wanted to be in Blink, he would have shown up to record [California], or he would have called us up and said, “My God, I don’t want out of the band at all.” But he didn’t. I’ve spoken to Tom one time since 2014 and it was cordial enough. But even then, when we were talking, I said, “If you didn’t want to quit Blink, you would have showed up or you would have called us.”

So you guys started talking about recording California prior to Tom leaving?

Hoppus: We were supposed to be recording this record! When Tom quit, our texts were [about] moving gear into recording studios to start recording. We were planning on starting recording the first week of January 2015. New Year’s Eve or the day before New Year’s Eve was when we got the email from his manager that he was out. And we even asked for clarification from his manager, “What does it mean that he’s out? He doesn’t want to record? He doesn’t want to play the shows?” He said, “He doesn’t want to do anything. He’s out.”

Matt, when you came on, to what extent did the three of you share songwriting on this record?

Matt Skiba: It was a collective effort for sure. Mark and I sang pretty much every harmony, every lead, everything to the point where it was like, “Did you write that, or did I write that?” It was just a matter of mixing it. We were all hands on deck.

When you guys tour and perform the older songs, will you be taking over all of Tom’s vocals?

Skiba: Yeah. I’ve always been a really big Blink fan, and I still want it to have that spirit, but bring my own voice to it. I’m not going to try to imitate [Tom], but there are certain pronunciations and certain things that have to still have that spirit. I try to be respectful of that for the band and for the fans, but also bring my own flavor to it.

Blink took Alkaline Trio on tour years ago, and our fanbase, like, tripled in size. All of the Blink fans were like, “Oh, this is a cool band.” There were always Blink shirts in our crowd. It’s been a really cool, amazing trip, and I’ve been really good friends with these guys for a really long time. It’s kind of like slipping into a really warm bath, if you will, to quote Hannibal Lecter.

Mark, how do you feel about Neighborhoods?

Hoppus: I like Neighborhoods. Neighborhoods was cool. I like the songs on that record, I like the production on it. It feels disjointed, listening back to it now. We were probably together [in the studio] one day out of ten. But I’m definitely proud of the music on it. I was working out the other day, and one of the songs from Neighborhoods came on my shuffle and I was like, “Oh, this is a cool song.”

From what I’ve read about the making of Neighborhoods, it doesn’t sound like you guys were in love with recording your parts separately.

Hoppus: It made all the difference on California to have all three people in the same room at the same time. We would get together for Neighborhoods and hash out some ideas, and everyone would say, “Okay, I’m gonna go to San Diego for a couple weeks and I’ll work on it and get back to you guys.” There was a separation. There’s a magic that happens when everyone’s in the same room at the same time, with the immediacy of like, “What about this word for that?,” or “That’s cool, but what about this?”

I think when people are jumping on top of each other’s ideas, it elevates it a lot more than me going into the studio and working on something all by myself for a while. By that point, you become so entrenched with what you’ve written that it’s hard to step back from that. We were working so quickly in the studio that Matt would be seeing something and say, “Is that good?” and I’d go, “Yeah, that’s awesome,” and he’d say, “Is that good?” and I’d say, “That could be better.” I need that feedback, too. Everybody was pushing each other, and it was just a much better result.

All of the various Blink side projects — Box Car Racer, +44, the Transplants — have involved expanding into genres beyond pop-punk. How would you all reconcile your diverging interests over the years when it came time to record a new Blink record?

Hoppus: There was a great push and pull of what Blink should sound like all the time. Travis comes from a different background than I do, and Tom comes from a different background than either of us in terms of what we write and what we think a song should be. Tom pushes me out of a box that I put myself in. I think I ground the melody and the harmony, and I think Travis takes a song that could be very pedestrian and makes it really interesting. On the past couple things we’ve been working on, it’s too far afield. Tom was looking for stuff that was very different from what Travis and I were playing. We like heavy guitars and angsty guitars and aggression.

Is there an overriding theme to California? There’s an anxiety to songs like “Rabbit Hole” and “Bored to Death.”

Hoppus: I don’t think there was a theme. I certainly wasn’t writing about anything differently than I think I ever have before. What I love about Blink is [that we write] catchy melodies with dark lyrics. Matt is great at that; I think he has an amazing talent for writing the most gorgeous songs that are about death and murder. At one point during the writing process, we were joking that we should call the album Death Blood because there were lyrics about death and blood and drowning and whatever. But no, I still feel like I’m writing from the same place that I did on [Blink’s 1995 debut album,] Cheshire Cat.

There are a couple of really silly snippet songs on California — “Built This Pool” and “Brohemian Rhapsody.” Both of those sound reminiscent of an earlier, more irreverent time in Blink’s history. What made you want to go back there?

Hoppus: [Producer] John [Feldmann] creates an environment of enthusiasm and lightheartedness and excitement. For “Built This Pool,” it was just something I was playing in the background behind John when we were between takes or something, and he said, “What’s that?” I said, “Oh, it’s just this joke I made up a while ago.” He said, “We gotta record that, we gotta record that!” So we just ended up recording it real quick. I don’t think any of us felt like, “Oh, we need to put joke songs on the record.” If we found something funny, we would record it, and if we wanted to, we’d put it on the record. It’s not really something we spent too much time agonizing over.

If you guys started out today and recorded your gross-out songs like “Does My Breath Smell?,” “Dick Lips,” and “Happy Holidays, You Bastard,” do you think Blink would have the same level of success that you did around the turn of the century?

Hoppus: I think so. We were always the butt of our own jokes. I think that people saw that we weren’t really making fun of anybody except ourselves. So I think the songs would still hold up. We’re still playing them 15 years later and having a great time doing it.