YG has gone full vegan. Grill-the-waiter-about-GMOs vegan. Pose-for-PETA vegan. And right now, the Compton rapper — the one who has tattoos snaking up to his chin, wriggling into his ear and curling atop his head, who chooses clothes the color of oxygenated blood, who spreads a street gospel that’s got even New York Bity bicken back and being bool — suspects there’s some non-organic s**t in his sparkling lemonade.

“They put soda up in this s**t?” he asks, inspecting his glass, narrowing his eyes. “Hey bro — y’all put soda up in this lemonade? Sparkling… that’s like acid s**t?” The waiter chirps that it’s just carbonated water. YG is not convinced.

“That’s organic?”

Organic, no GMOs, made in-house. Just water, lemon, agave.

Also Read

YG Shares ‘Out on Bail’ Video

“Agave? Ain’t no acid?”

No. One-hundred-percent natural.

YG nods, almost satisfied. “That s**t break my face out.”

Gracias Madre is about as far away from Compton as you can get, figuratively speaking. Situated catty corner from SUR, the restaurant owned by Beverly Hills queen pin Lisa Vanderpump, this fancy, 100-percent-vegan taco joint is frequented by people like Elizabeth Berkley, who just breezed past our table.

And YG. This is his favorite restaurant since becoming a vegan a few months ago.

Digging into a plate of cauliflower tacos (surprise: they’re tasty, or in YG’s words, “S**t fire, nigga!”), he says health reasons are why he cleaned up his diet. “People dyin’ from cancer. No microwaves, you feel me? Alkaline water. I do my fruits, I do my organic greens, gluten-free s**t, no GMO in my food,” he says. “Everybody say I lost weight, my skin look clearer.”

Indeed, his belly pooch, which grew commensurate with steady paychecks, has deflated. His neck and face have slimmed. On this warm, late March weekday, he’s decked out in olive trousers and bomber jacket with a pair of snow-white Nike Cortez and a custom-made bracelet of red Converse shoe charms. Maybe it’s the clean living, or just the power of suggestion, but his skin really is glowing. He’s handsome, made more so by the ease with which he jokes and teases everybody around the table.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”197602″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2016/06/yg-still-brazy-new-album-spin-cover-story-2-300×133.jpg”]

It’s ironic, though, that a healthy, barely 26-year-old is concerned about dying from cancer. Or, more accurately, it’s ironic that YG is concerned about dying from cancer. After all, he faces a much more urgent threat — Gloves, his bodyguard, sure ain’t here for the food. On June 12, 2015, YG was shot while recording in a complex of pricey live-work lofts near Universal Studios. A single bullet pierced his hip in three places, but it bypassed a large artery and by the next day, he swung his crutches back into a studio. Perhaps monitoring his food intake so strictly is a way to wrest back some control: He says he still doesn’t know who set him up or who pulled the trigger.

In a disturbing way, this subplot is consistent with YG’s storyline. Belonging to the Tree Top Pirus, a branch of the Bloods that controls a cluster of streets with names like Spruce and Maple, he still has one foot firmly planted on the corner and is a throwback to an era when the LAPD swarmed Compton’s skies with ghetto birds and stormed their streets with batterams. An L.A. in which The Chronic blasted from every car hitting switches on Slauson when the sun went down and streamed outta boomboxes during backyard barbecues. An L.A. that assigned women to one of three categories: mama, bitch, or ho. An L.A. that rode tricked-out Chevys, slugged 40s of Olde English, and wore khakis (f**k jeans).

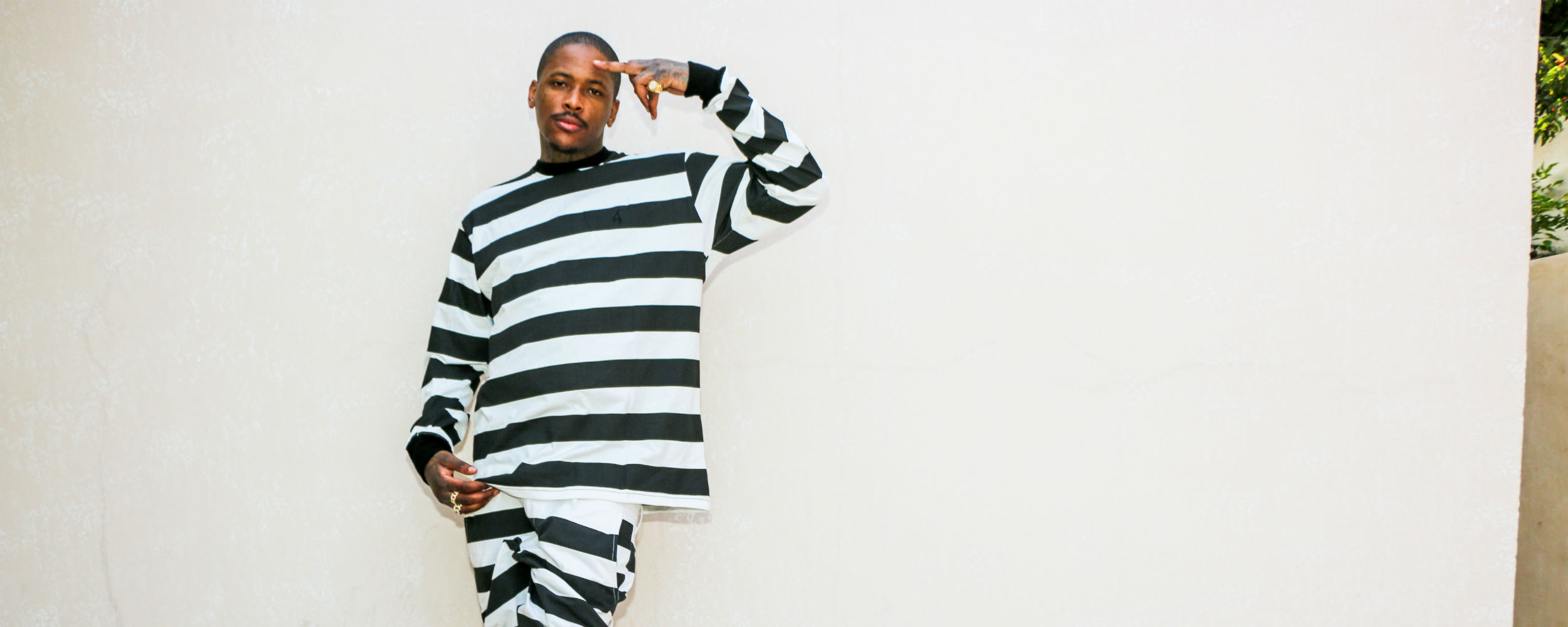

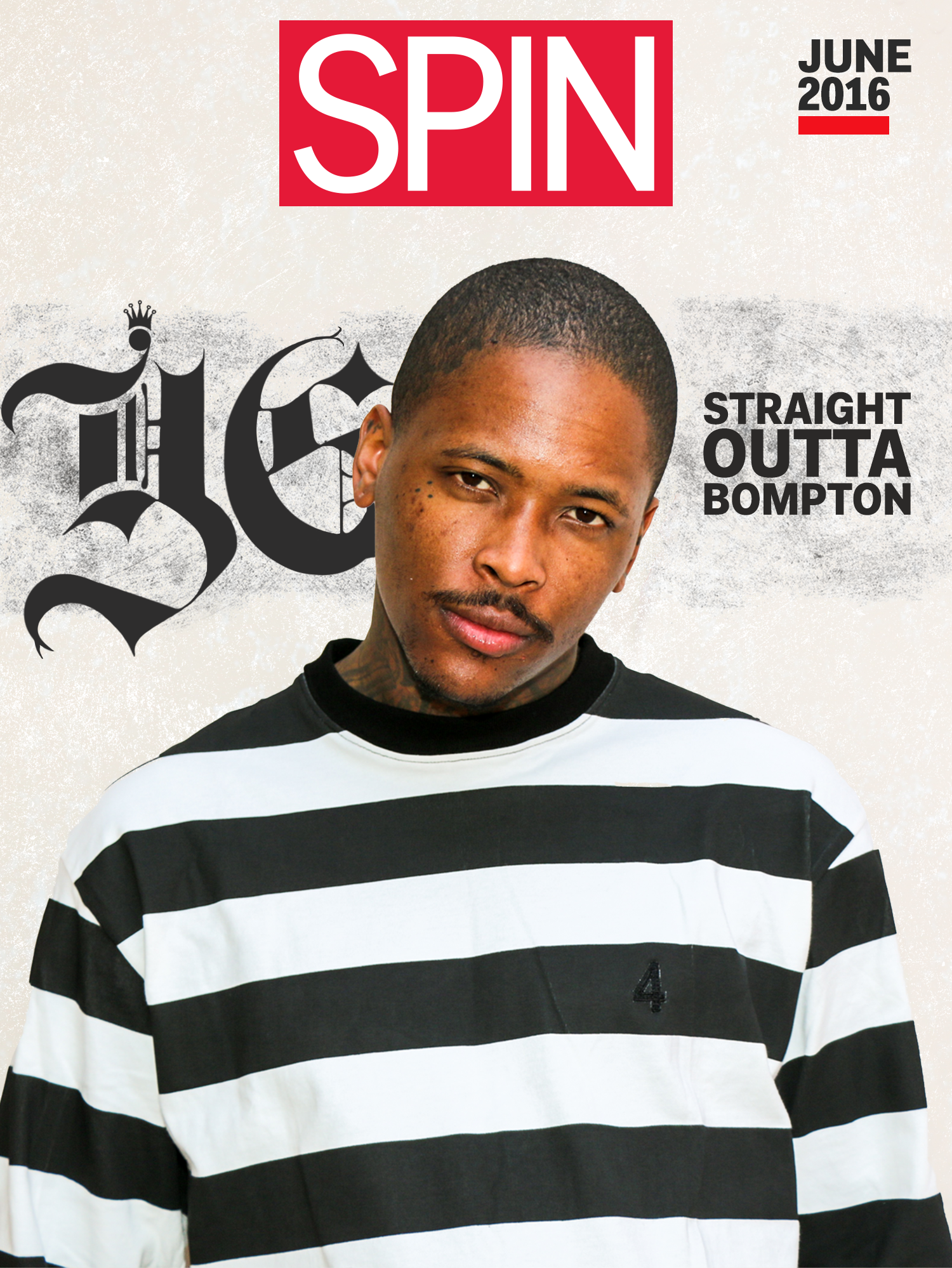

YG even dresses like he stepped out of ‘92, scissoring off the pant legs of his chinos, donning bowler hats or perching snapbacks on his head, sporting duck jackets and plaid button-ups. The outfit he wore to Coachella this year — a white-and-black striped T-shirt tucked neatly into jeans — looks almost identical to a 1990 picture of Dr. Dre.

Recently, his music has started to slink with that G-funk strut, too. It wasn’t always that way. After dabbling in jerkin’, YG became the face of ratchet when he teamed up with DJ Mustard and Ty Dolla $ign in 2008 and released the wham-bam-thank-you-ma’am hit “Toot It and Boot It.” Climbing the Billboard charts, it was bumped round the clock on local hip-hop station Power 106 and scored YG a deal with Def Jam by the end of 2009.

“I see YG making real waves and changes,” says executive producer Randall Medford. “[Malcolm X] had that street background, they respected him. I can see YG going that direction.”

Five years later, a handful of rowdy mixtapes had made him the people’s champ in L.A. and a platinum single, “My Nigga,” had beefed up his Bank of America account. In March 2014, his cinematic major-label debut, My Krazy Life, entered the Billboard Top R&B/Hip-Hop chart at No. 1 and sold 61,000 copies in its first week. A gleeful day in the life that opens with his mama hollering at him to not hang with bangers, the album was primarily produced by Mustard, who by then was the most influential producer on the radio. Landing on all of the major best-of lists at year’s end, My Krazy Life introduced the country to Blood slang, which replaces C’s with B’s, and proved YG could craft more than slurred party-starting odes to oral sex. He was a bona fide Album Artist. In an interview, YG said Young Jeezy, the mentor who helped break him out of the West Coast, advised him not to alienate those who deride gangbanging by naming his first album “I’m From Bompton.” This time around, he knows his affiliation is a bonus. The title of his sophomore album, due out June 17? Still Brazy.

In a word, YG is real. “I been in the streets for a long time. They know me. They see me. They heard stories,” he says. “A lot of artists don’t got that credibility s**t. They don’t got they city on lock. I got that. That’s special. You can’t take that away.”

Of course the streets love him. But the reason he’s won over the rest of the country is because wannabe, never-will-be thugs love him, too. Early songs like “Pop It” and “Pussy Killer” have that party-and-bulls**t vibe a generation weaned on bling-bling and jiggy rap want. He’s also what they can’t be — a real gangbanger — but he makes the kind of music they can live vicariously through. Pinning their geeky fantasies on him, they pretend that they, too, can twist their fingaz and get a hood pass.

And suddenly, he’s wrangling a different crowd altogether: the political one. Not only has he tweeted reminders to vote, he’s also voiced support for several local candidates. And he might be accused of inciting street justice, but he’s the only notable rapper to stand against Trump on record. His and Nipsey Hussle’s protest song, “FDT” (F**k Donald Trump),” has even put YG on the federal law enforcement’s radar, just like N.W.A was in the summer of 1989.

Perhaps no one saw it coming when “Toot It and Boot It” reigned supreme on the radio, but YG could be one of the most important figures of his generation. “I see him making real waves and changes,” says Randall “Sickamore” Medford, who executive produced both of YG’s albums. “[Malcolm X] had that street background, they respected him. I can see YG going that direction.”

Yet that asset could also be his downfall. He knows it, too. When I ask what his biggest vice is, he doesn’t hesitate: “The streets.”

Born Keenon Daequan Ray Jackson, YG grew up all over L.A. His mother, a native Angeleno, ran a daycare business in Paramount and set up his dad, who was originally from Atlanta, with another location in Long Beach.

You can hear the south in YG’s voice — “baby” and “hungry” uncurl and become “behhhbeh” and “hongry” — but his father’s way of life couldn’t compete with Compton’s. Still Brazy starts with his pops practically shaking his head, saying, “I told your mama she shoulda moved.”

“My mom and her whole side of the family, they all from Compton. She wasn’t tripping. It was where she was from. My pop from [the South] so he like, ‘Naw, this s**t ain’t cool, my kids can’t be involved,’ but he went to jail and I hit the streets,” he says.

His dad had steered him toward sports, and YG, a natural athlete, excelled in pretty much everything, but once he started banging, he gave them up. After both parents were charged with tax fraud, they lost their house and moved in with YG’s grandfather. With his father in jail and his mother juggling jobs at the grocery store and McDonald’s, YG ran wild and got kicked out of school.

When he was 16, though, he also started rapping, and when he posted his songs on Myspace, they went viral. Another teenager who went by the name of DJ Mustard was already spinning YG at parties when a mutual friend connected the two.

But in 2008, YG’s lifestyle caught up with him. After a friend asked him to go “flock” (their term for robbing, detailed in My Krazy Life’s “Meet the Flockers”), he tripped a silent alarm, was apprehended, and found himself facing two years in the penitentiary. Fortunately, the mother of a girl he knew in high school worked in the courthouse and wrote the judge a letter on his behalf. Acquiescing, the judge sentenced YG to six months in county jail instead.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”197642″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2016/06/yg-still-brazy-new-album-spin-cover-story-3-300×133.jpg”]

“When that happened, I was like, ‘Oh s**t, I’m blessed!’” he says, laughing in disbelief. “That’s why I believe in God. I ain’t even mention, when I was in jail, they brought up three more cases that had my prints and all that s**t. But I ended up getting out of jail with no new case. I finna got washed! Real talk! Forreal, forreal, forreal!”

Within months of being free, YG was signed to Def Jam. In the beginning, YG and Mustard attracted attention with giddy party anthems like “I Like Head” and “Patty Cake” that were built on the back of a stripper-ready sound born in Louisiana. Tapes like 2012’s 4Hunnid Degreez were chockful of club bangers, but the guys always had bigger plans. “He went from being a ratchet rapper to a classic West Coast storyteller,” says Sickamore.

That muscle continues to develop on Still Brazy, with YG revealing a new vulnerability drawn out by having a baby girl, Harmony, who just turned a year old.

“[The song written for Harmony] was basically telling my daughter about myself before anybody could tell her. My flaws, ‘bout how me and ya mama was around that time,” YG says of the song, which ultimately didn’t make the album. Though he doesn’t say that he and Harmony’s mother are a couple, they seem to be co-parenting well, wearing matching airbrushed jean jackets at the baby’s birthday party and squabbling over YG’s insistence on overhauling Harmony’s diet, too. “For a dude like me to have a daughter? It’s different.”

For all the changes in his life, there remains one constant: YG’s love for his block. He’s always peppered his songs with mentions of it, which is why on a chilly spring Saturday a few weeks after our initial interview, I know I’m in Bompton when I see the Tam’s Burger on Rosecrans.

Despite a concerted effort to distance today’s Compton from N.W.A’s Compton, a recent article in the Los Angeles Times rang an alarm: There have been 15 killings so far this year — two more than in the entirety of 2015 — and sheriff’s officials claim most are gang-related. People still warn you not to go to Compton. Before I headed down to the CPT, Still Brazy’s other executive producer, Steven “Steve-O” Carless, was incredulous. “Yikes!” he emailed. “Be careful!!!”

Most people, if going to Compton at all, take the 110 to the 105. But doing so erases the part where you catch downtown’s skyscrapers, $5-an-hour parking meters, and the aquamarine jewel of the Omni Hotel give way to the liquor shops, pre-approved payday loan storefronts, and Metro PCSes of Compton. If you drive down Figueroa or Vermont or Normandie, you see the full scope.

Clearly, the city of Compton still struggles with poverty. Last year, its unemployment rate was 12.7 percent, 32 percent higher than in 2000. The streets are wide, but the neighborhoods are cramped. Houses sit on small lots with no yards and few have been renovated, a coat of lilac or seafoam-green paint doing what it can to add cheer. While the rest of L.A. is brunching and wandering into boutiques, Compton is eerily still. There’s not much window shopping to be had down here. A lone man sits at a bus stop. Inside a hair supply store with too many empty shelves, a woman eyes me and my friend warily. Even the flies hovering above a sticky table in a Chinese donut spot circle lazily.

Sectioned off by Rosecrans on the north, the Tree Top Piru territory is surprisingly small, running for fewer than ten blocks. Blink and you’ll miss it. The 400 set — the clique to which YG belongs — is east of Aranbe, and at its heart seems to be Washed Up, an auto-detailing outfit that appears often in YG’s promo shots.

The neighborhood does look less colorful. Besides a ripped dude cutting across the street in a cherry-red durag and shorts, there are no obvious signs that TTPs have marked this part of town.

“I mean, s**t. It’s the same, really. It ain’t as rowdy as older homies say it used to be back in the ‘90s,” YG says of current-day Compton. “But the younger dudes out there, they look like they ain’t all-the-way gangbangers. They really be strapped down and all that. It ain’t so much red-and-blue s**t — that ain’t so much going on how it used to be.” When it comes to the cops, he says, the more things change, the more they stay the same. “Police still the police. Still watching motherf**kers. Motherf**kers still getting killed,” he continues.

“I can’t do no weird s**t,” YG says. “‘Cause I’m from the streets. My peoples, my foundation, they gotta accept this s**t too.”

Mayor Aja Brown is trying to root all that out. A millennial herself, the 34-year-old is the youngest mayor in Compton’s history, and she too recognizes YG’s influence in the community. Not long ago, she spent more than two hours in the studio with him, listening to his music and talking with him and his friends. “Mayor Aja Brown really trying to help. Mayor before her f**ked up stuff. He tricked off all the money, dumb s**t he did. She fixing all that s**t,” he says. “And we helping ‘em.”

“He’s an authentic homegrown hero,” says Steve-O, who met YG in 2009. “When we’re watching TV, he’s giving back opinions as if he’s talking to the people. He goes to sleep at night, wakes up, and raps about it in the studio. He’s become sensitive to all sorts of topics around him.”

Such as the one that led to recording “FDT.” According to the 2010 census, 65 percent of Compton’s population is comprised of Hispanics. That’s the Compton YG grew up in.

“[Trump’s supporters] f**k with him ‘cause what he on about Hispanics. It’s disrespectful and they really ain’t got nobody speaking up for ‘em right now,” he says. “Me and Nip know the majority of our supporters, at the shows, buyin’ albums, they Spanish. So we have to speak up. The streets been supportin’ me the whole time, so I gotta do the same.”

Longtime friends, he and fellow South L.A. rapper Nipsey Hussle had a phone conversation about Trump’s inflammatory hate-mongering and decided something had to be done. Still, since cops had shut down his shows before, YG figured he’d been red-flagged by the LAPD and was hesitant to make such a bold statement.

“We gonna go HAM and they gonna come for us and shut our whole program down,” he says of his concerns. “But this Donald Trump s**t, nah, he doing too much. I don’t know, I think all that s**t fixed. But if he win, it’s gonna be bad for us.”

Since its release, “FDT” has been heard outside numerous Trump rallies around the country, but the song’s most powerful moment might have happened right here at home during the video shoot.

“Police [had] to stand back while Bloods, Crips, and Mexicans walked down Crenshaw in the middle of broad day with a peaceful protest,” Hussle, who is a Crip himself, tells me over the phone. He’s still astonished that he and YG were able to create solidarity, but it’s no surprise coming from “two of the voices of the street.”

Downtown’s garment district is like an overstuffed closet. Mannequins crowd the sidewalks and merchandise explodes out of shoebox-sized shops.

“You seein’ me on some creative s**t today. Some backend business. Feel me?” YG says, strolling down the aisles of one of the bigger and more organized stores. He’s never been here before, but it’s time to choose fabric for samples of the new 4Hunnid clothing line. This is part of the master plan: expand to fashion and build an empire.

“I got my own look. So instead of me going and putting somebody else s**t on and making they s**t look good, I’m gonna create my own s**t. This s**t unexpected from me. I’m challenging myself everyday,” he says. “I ain’t gon’ do what every rap nigga do. Everybody else can do some corny s**t. I can’t do no weird s**t. ‘Cause I’m from the streets. My peoples, my foundation, they gotta accept this s**t too.”

It’s about inspiring other people to be entrepreneurs as well. One of his favorite parts of being a rapper, he says, is that he gets to travel the world. He picks up a fabric printed with dollar bills. He wants to line all the pants’ pockets in his collection with it.

Passing by a stack of weed prints (he’ll sip Hennessy or Patron, but “ain’t a weed smoker”), he finds plenty of reams that catch his eye, murmuring, “OoooOOO. That’s hoard!” over a flame print reminiscent of Guy Fieri and a camouflage print concealing curvy women (“Camouflage bitches! Now you see ‘em, now you don’t!”). Then he asks me to take a photo of him unspooling a bright-red bandanna fabric.

He can’t help himself.

“Go to the hood, go gangbang a little with the homies? That’s the s**t I like!” he says. “It’s bad, though. Every time I go, it’s always some s**t. But ‘ay, that’s the beauty of the beast. It ain’t beauty though. But we act like it’s beauty. We love it like it’s beauty.”

“It’s a tough navigation,” Sickamore agrees. “YG’s not one of those people who wanna go live in Europe and chill on the beach. He’s very integrated in his neighborhood. He’s good with the mayor now. He really believes in community. He’s never gonna stray too far, for better or worse. You worry about it, but you’re always gonna go home. He thinks about it like, when the music’s over and things are not happening, you have to come back to your ‘hood and you don’t want people to feel like you sold them out.”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”197661″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2016/06/yg-still-brazy-new-album-spin-cover-story-4-300×133.jpg”]

YG and I are dancing to Still Brazy. It’s late afternoon in early May, a month or so after our first interview, and we’re bopping around a studio tucked off the freeway heading toward the Valley. I’m already rapping the hook of a song titled “Bool, Balm and Bollective” as YG laughs and bobs his head. He has that relieved, almost-there energy you get when you’re this close to scratching some big task off your to-do list.

He’s just played me the full album, and it’s terrific, both thematically and in its ability to go dumb and drop the bottom out of your car. Instead of repeating My Krazy Life, he’s used it as a springboard, turning that unblinking eye of his from the past to his present. Browse the song titles — “Who Shot Me?,” “Police Get Away Wit Murder,” “Don’t Come to L.A.” — and you get a pretty good idea of where YG’s head is at. With creeping synths and lyrics like, “Lately I got a pistol when I answer the door” or “I’m a nigga and I can’t go outside,” paranoia clearly is the biggest motif.

Features include Lil Wayne and Drake, as well as old friends like Joe Moses and one-to-watch Kamaiyah. With production from Terrace Martin, the multi-instrumentalist who cut his teeth touring with Snoop Dogg, and the Bay Area’s P-Lo (as well as DJ Swish, Hit Boy, and CT Beats), the record finds inspiration in Dre’s Death Row, but updates it with the bounce YG’s always been known for.

Noticeably absent, of course, is DJ Mustard. Last year, a spat over money bubbled up on social media, but it was so quickly contained that some thought it had been manufactured. Yet as YG revealed on his Instagram in April, the two went a “real 365” days without speaking.

Slipping up on his diet due to studio life — he slept here last night — YG sits down to eat a chicken sandwich. He and Mustard have made up now, and, dragging a fry through ketchup, he explains that their friendship faltered due to “being young and successful and not knowing how to deal with success.” But the riff had an unexpected consequence. Musically, it pushed YG into the deep end, alone.

“Mustard not being there was huge because he was such a big component of the last album. These guys are childhood friends,” Steve-O says. “To not have that, [YG] really dug deep and pulled out an amazing body of work. It was a very tumultuous 18 months. Most people would’ve folded.”

Outwardly at least, YG appears unfazed. With the exception of the Secret Service nagging Universal over the lyrics in “FDT” — YG really wanted it on the album, and Steve-O tells me later that they muted the direct threats to get the okay — everything in YG’s life has fallen back into place. Well, with one glaring exception.

In YG’s mind, there’s a practical reason he was walking the day after he got shot. Like he chanted on “No Sleep,” from his 2013 mixtape, Just Re’d Up 2, “If I don’t grind, we don’t eat.”

“I ain’t come from money. If I wasn’t in my situation, it’d be all bad. I got brothers, sisters, a pops, and a mama. It’s all on me, pretty much. And I got my daughter now,” he says, padding across the kitchen in Tom’s slippers to grab a bottle of alkaline water. “I’m trying to make sure my kids’ kids got paper.”

Still a good Southern Baptist in theory, if not in practice, I found myself stopping to pray for YG over the course of reporting and writing this feature. Because just like Sickamore, I too think YG has been set apart for a great purpose. While many have tacked that hope onto Kendrick Lamar, he can be esoteric, a theologian, while YG is plainspoken, a man of the people. Kendrick isolates and struggles alone; YG wants to be in the middle of the fray — too much so, sometimes. It’s easy to feel a kinship with YG because he keeps going back to the one thing he shouldn’t.

Plus, he needs prayers. Not two weeks after we hung out at the studio, the video shoot for YG and AD’s “Thug” was shot up. No one was arrested or injured, but police found casings from an AK-47 and told TMZ that the incident seemed to be gang-related.

Does it scare him, not knowing who’s after him?

“Yeah, like…” he trails off and his eyes, slitted, slide toward me. “I’m always lookin’ over my shoulder.”

He believes God saved him. Saved him from doing years in the pen, saved him when he got popped. “I got the Lord. He with me, right behind me,” he says. “Somebody was after me, I wouldn’t be here.” Evidencing his faith in that, he even had a Bible verse, Isaiah 54:17, tattooed on his shaved crown: “No weapon formed against me shall prosper.”

Times like these require a little bit more than faith, though. He pulls open the front pocket of his trousers. The cash fabric isn’t in there.

A pistol is.