On May 25, 2016, New York hip-hop suffered a tragedy when a shooting at T.I.’s Irving Plaza concert killed rapper Troy Ave’s bodyguard, Ronald McPhatter. Troy Ave (who sustained a gunshot wound to the leg that same night) has been the only person arrested in the investigation, but the entire genre — as per usual — is being held accountable for a single incident. The consequences were immediate: Scheduled Vince Staples, Mac Miller, YG, and Joey Bada$$ concerts at Irving Plaza and Gramercy Theatre were canceled because venues were “acting with an overabundance of caution and coordinating a going forward strategy with the New York Police Department that may also include a curfew,” according to a spokesperson for the two venues.

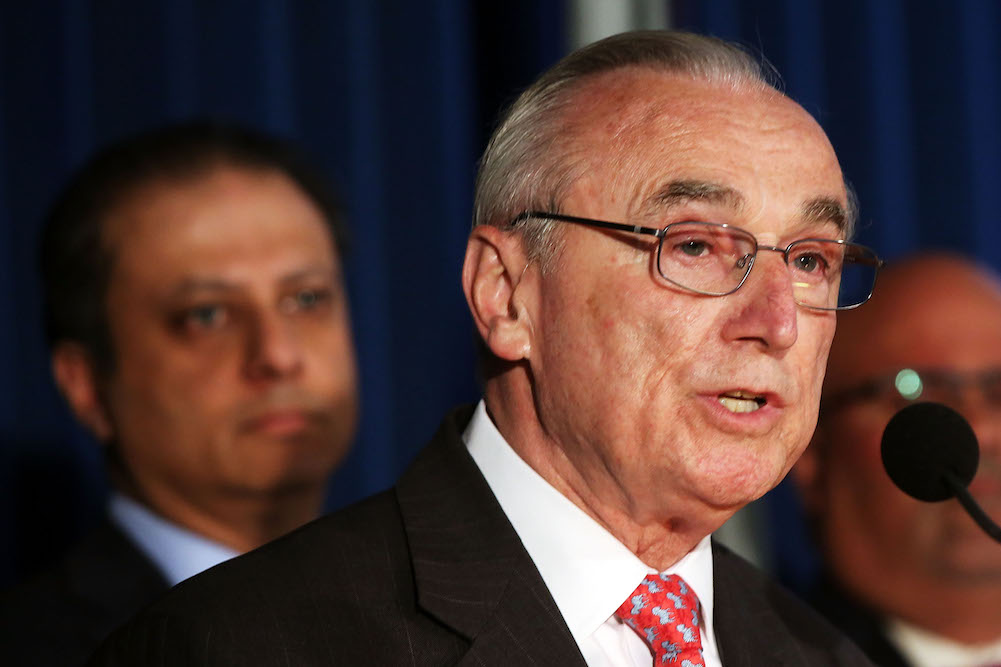

The disappointment for hip-hop fans was vindication for the NYPD. Commissioner Bill Bratton was more than ready to go on radio the morning after the shooting to denounce hip-hop as being a “crazy world” whose inhabitants are “thugs.” Bratton didn’t even have the decency to call rappers “rappers” — just “so-called rap artists.”

But his comments shouldn’t come as a surprise — Ice-T‘s role on Law & Order: Special Victims Unit hasn’t single-handedly mended the fraught relationship between law enforcement and hip-hop. This tension is an ever-present undercurrent within the culture’s birthplace, where many police appear to see its figures as young black men itching to commit crimes.

The scrutiny isn’t just genre-specific, of course. Historically, movements that have given African-Americans a voice have been met with opposition by law enforcement. COINTELPRO, an FBI project that sought to dismantle political movements through the ’50s and ’60s, stands as a savage example. Hip-hop is one of the most prominent black-led phenomena in the culture today, and it’s long been under the scrutiny of a police department eager to justify its own invasive practices. The following is a timeline detailing some of those measures, beginning after the 1997 death of the Notorious B.I.G. and the consequent genesis of a specific NYPD unit known as “the hip-hop police.”

Also Read

The Senator Is Pissed Off

1999 — Derrick Parker, Hip-Hop Cop, Is on Duty

Nowadays, former NYPD detective Parker is more or less known as the de facto spokesman of the hip-hop intelligence unit — he’s been very open about his experiences as an officer on that team. In fact, because of his intel, the NYPD sent him to consult the Miami police in 2001 to help them prepare for that year’s Source Awards. A few years later, in 2004, Parker told Village Voice that as a member of the Cold Case Squad, a unit dedicated to backlogged homicide cases, he noticed “that the rap music industry was becoming more like organized crime.”

“What interested me was I saw a lot of these guys that were really bad dudes in Brooklyn starting to latch onto rappers and entertainers,” he said to the Voice. “So I used to monitor the incidents, department-wide, of anything that happened.”

Parker said that after the Notorious B.I.G.’s ’97 murder in Los Angeles, “everybody’s eyes became open” — a roundabout way of saying that people bought into the belief that hip-hop causes gun violence. Thus, the hip-hop intelligence unit was born. Parker became a known presence.

“Puffy and J.Lo, I was called three in the morning. ‘Get up, you got a shooting up at midtown,'” Parker said of the Club New York shooting incident that saturated NYC tabloids and landed Puff Daddy affiliate/Bad Boy artist Shyne in jail for nine years, on a conviction for first-degree assault. “When [Wu-Tang Clan’s] ODB got pulled over in Queens with the drugs and he was sleeping on the cell floor, I was there.” Parker said that the unit’s goal was to “assist” rather than criminalize.

But like the motto “Protect and Serve,” Parker’s defense seemed naive. Attorney Kamau Franklin offered a cautious rebuttal: “I think he’s only within his job to do something about these situations if he has specific evidence that these people are engaged or involved in something. Otherwise he’s giving rationales and excuses for witch hunts.”

2000-01 — The Tunnel’s Final Years

Nightclub drug overdoses made news and Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s “quality of life” campaign was in full swing at the turn of the millennium, so Manhattan’s legendary hip-hop nightclub the Tunnel was definitely going to be under heavy surveillance. Although NYPD pressure existed before the new decade, a November 2000 Village Voice article detailed just how exhaustive policing and security had become. The piece described the Tunnel as if it was a prison compound with legendary DJ Funkmaster Flex on the turntables:

After kicking off their footwear and passing through a metal detector, everyone without exception endures a body search bordering on indecent by the Tunnel’s bouncers. “Should I take my socks off as well?” a young woman jokes with security. It’s difficult to imagine a predominantly white crowd out for a night on the town putting up with indignities like these.

The Tunnel had its fair share of problems that ended in fatalities, but so did other, more dance-centric clubs: Club Limelight party promoter Michael Alig was convicted for the murder of drug dealer Angel Melendez and Chelsea’s Twilo was the site of multiple overdose deaths. The Tunnel finally ceased operations in 2001 after accruing more than $1.8 million of back taxes and fines. Owner Peter Gatien was eventually deported back to Canada after pleading guilty to tax evasion.

Parker described the closing of the Tunnel as a “weight off the NYPD”: “The crime stats in the 10th Precinct went down a lot. Most of those [earlier] stats could be attributed to the Tunnel — the slashings, the shootings, assaults, larceny.”

April 2001 — “Crime Trends in the Rap Industry” Report Is Exposed

The New York Post reported that the police’s intelligence division was compiling a database to keep track of more than 40 rappers. “We are not targeting specific individuals or people in the music industry,” NYPD spokesman Brian Burke said in a statement that appeared to contradict the specificity of the database’s title: “Crime Trends in the Rap Industry.” “We just have a list of people that have been arrested already to prevent further crimes.”

The new tactic came after Foxy Brown and some associates of Queens rhymers Capone-N-Noreaga engaged in a shootout with Lil’ Kim’s squad outside of Hot 97’s studio on February 20, 2001. But then-interim New York Civil Liberties Union Executive Director Donna Lieberman wasn’t quite sure if the special measure was a fair one. “The police department is authorized to investigate based on suspicion,” she said. “But you can’t stop people based on race or music association. This is no more acceptable than racial profiling.”

March 2004 — Miami Police Ask the NYPD for Help

In the spring of 2004, the Miami Herald released an article detailing the Miami police force’s rapper surveillance. Officers photographed artists as they left hotels and stalked the video shoots and nightclubs they attended. “The last thing we need in this city is violence,” said Assistant Miami Beach Police Chief Charles Press.

Since the NYPD had more experience with the rap industry, Miami cops looked to them for guidance. A Miami officer told the Herald that the NYPD led them in a “three-day hip-hop training session,” sharing a six-inch-thick binder listing rappers and crew members who had arrest records. The binder began with 50 Cent and ended with Ja Rule, according to the Herald. The biased nature of this method of policing wasn’t lost on some critics.

“This kind of conduct shows insensitivity to constitutional limitations. It also implicates racial stereotyping,” said attorney Bruce Rogow.

Despite contradicting evidence, the NYPD refused to admit the existence of a hip-hop task force to the Herald. A Village Voice article released a week later finally got an NYPD officer to confirm, on-record, that there is an “intelligence squad” dedicated to the hip-hop scene.

August 2005 — The Smoking Gun Leaks Hip-Hop Dossier

A year after the Miami Herald‘s reveal, The Smoking Gun got its hands on the 500-page dossier that contained extensive info on multiple hip-hop figures: mug shots, arrest records, social security and license plate numbers, and filed police reports (50 Cent, the man behind 2005’s “I Don’t Know Officer,” reporting multiple assaults stood out as noteworthy). Jay Z, Busta Rhymes, Roc-a-Fella founder Damon Dash, Ja Rule, and Fabolous were just a few of the big names on the list.

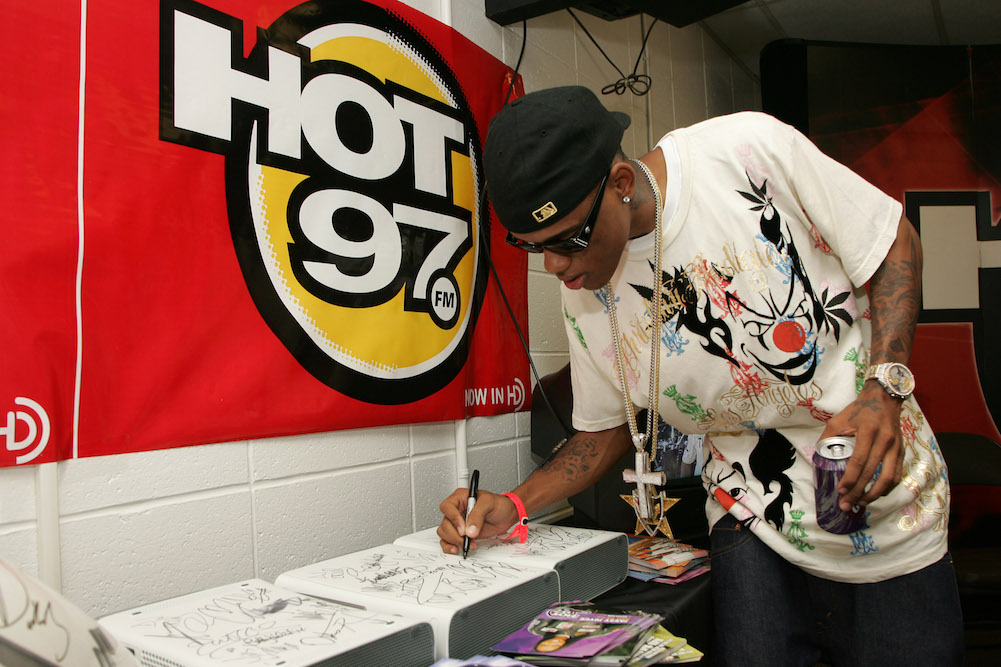

May 2006 — NYPD Installs Cameras at Hot 97

It took Jamal “Gravy” Woolard doing a Hot 97 freestyle with a bullet in his butt for the cops to take extra policing measures at the storied station. With the Foxy Brown/Lil’ Kim shootout still in mind, the NYPD decided to place a surveillance camera outside of Hot 97’s Hudson Square offices. The camera was one of the first in the NYPD’s plan to install high-tech video recorders throughout the city. “We’ll keep it in place until Hot 97 is evicted or cleans up its act,” a police source told the Daily News.

January 2014 — NYPD Monitors Rap Videos

In an effort to stymie gang violence, the NYPD started using videos as “evidence” to build cases against suspects. In an article published in January 2014, the New York Times reported that the strategy was part of a shift in focus from invasive stop-and-frisk tactics (long biased against young black men) toward long-term investigations of neighborhood sets. The police haven’t hesitated to use this method: Na Boogz, a Bronx rapper and alleged gang member, was indicted on conspiracy charges in 2012 because a video for a diss track was used as evidence against him.

Boogz, born Shaquille Holder, maintained that he’s part of a legit music group. Whether that’s actually true is a bit ambiguous. (Holder himself admitted to the Times that he “can’t say that everybody [in his crew] is living the straight and narrow life.”) What’s less ambiguous is how the police refused to buy the art-as-fiction defense that’s allotted to artists in other genres.

April 2014 — CD Peddlers Sue NYPD for Wrongful Arrests

People who frequent Times Square are familiar with hip-hop CD peddlers, and many of those street sellers are personally familiar with the police. In 2014, eight rappers filed a joint lawsuit against the city and 17 individual cops, claiming they were unfairly arrested for trying to hock CDs. The plaintiffs said they complied with the law but still got booked on charges for disorderly conduct and aggressive begging.

The rappers believed that the NYPD started hassling them more after aspiring MC Raymond “Ready” Martinez was killed in a shootout with a cop in 2009. Some simply pled guilty to the “bogus” charges to get out of their legal predicaments faster. Bronx rapper Andre Jackson tried to fight the charges in 2012 based on principle. “They never arrest the spray-paint guys,” he said to the Daily News. “They never arrest the guys who draw pictures of people. That’s considered art? My music should be considered art, too.”

October 2014 — Drake Gets Added to the Hip-Hop Police Watch List

Despite being the face of one of the world’s biggest corporate brands, Drake is on the hip-hop watch list. In 2012, at the Manhattan club W.i.P., Drake and Chris Brown’s respective entourages got into a skirmish that ended in broken champagne bottles, Brown getting a bloodied chin, and NBA star Tony Parker almost losing an eye. After W.i.P. shut down less than a year later, Page Six reported that both Drake and Chris Brown were added onto the hip-hop police’s watch list because of the fight.

“They don’t want any situations like the Suge Knight shooting,” said a source, referring to the Death Row boss’ 2014 shooting at a pre-VMA party. “If something does go down, they want to already be on the scene.”

The report reminded readers that the hip-hop police still existed, and made it clear that even Toronto’s rapping mascot could draw the ire of the hip-hop police after just a single incident. It also elucidated how little faith the NYPD has in rappers as self-governing, grown men.

“Let’s say there is a show… and they know there’s a beef going on that could escalate to a fight or shooting,” the source continued to Page Six. “The police may say they need to change set times and they don’t want two artists like French Montana and Jim Jones to perform too close together. Then they’ll go and watch. They’ll go backstage.”

May 2016 — GQ Examines Shady Details About the Bobby Shmurda Case

After getting arrested in December 2014 for charges including reckless endangerment, conspiracy to commit murder in the second degree, and criminally using drug paraphernalia, rising Brooklyn artist Bobby Shmurda went from being a surefire star to a big-name target of NYPD’s hip-hop surveillance. Cops stood guard at his shows (even at his Tonight Show performance) and rapper Troy Mclean (also known as Ball Reckless) recently recalled to GQ that Shmurda’s crew was harassed at gunpoint on one occasion. At a news conference following Shmurda’s arrest, an NYPD police chief called the lyrics to his breakout hit, “Hot Nigga,” “almost like a real-life document of what they were doing on the street,” and placed Shmurda’s government name, Ackquille Pollard, atop the list of indictments, as if to make an example out of him.

“There is no question that Ackquille Pollard is the driving force behind the GS9 gang [Shmurda’s crew and fellow defendants] and the organizing figure within this [gang] conspiracy,” a prosecutor said at the arraignment.

It turns out, though, that plenty of questions remain. GS9 allegedly took part in illegal drug-related activities, but GQ pointed out that there’s been no interrupted drug transactions and no narcotics inventory shared by prosecutors as evidence. With its increased focus on gang-busting, the NYPD runs the risk of treating young black men from low-income neighborhoods as if they’re part of some criminal organization. Right now, it looks as though Bobby Shmurda is simply guilty by association, regardless of whether he actually committed the crimes he stands accused of. “You put them together as a gang and they’re all responsible for all their criminal activities,” John Jay College of Criminal Justice researcher David Kennedy told GQ.

Just days before he was set to stand trial, Shumrda pleaded guilty to fourth-degree conspiracy and second-degree criminal weapons possession. He was sentenced to seven years in prison but will receive credit for the two he has already served.

May 26, 2016 — Bill Bratton Calls Rappers Thugs (and “So-Called Rap Artists”)

The morning after the shooting at Irving Plaza, Commissioner Bill Bratton went on WCBS 880 to slander hip-hop. “The crazy world of the so-called rap artists who are basically thugs that basically celebrate the violence they’ve lived all their lives and unfortunately that violence often manifests itself during the performances and that’s exactly what happened last evening,” he said on air.

Bratton revealed he had a very loose, askew interpretation of the word “often.” He also didn’t cite any other instances of gun violence at rap concerts. Suddenly, one incident is an indictment against an entire culture. Same as it’s always been.