It’s been 20 years since the future that legendary electronic group Underworld faced was shining its brightest. The long journey of Karl Hyde and Rick Smith began in the early ’80s, with the pair achieving minor success in the new-wave band Freur. Then, with a pared-down lineup and a new name, the duo went on to have an abortive late-’80s run playing synth-rock as Underworld (days the duo now refers to as “Underworld Mk1”), before adding the younger DJ Darren Emerson and taking off as a reinvented stadium house act.

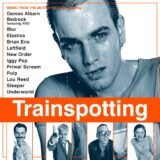

In 1996, the group’s “Mk2” incarnation hit its peak after the unlikely crossover success of “Born Slippy .NUXX,” a euphoric club stomper initially wasted as a B-side, before being showcased in Danny Boyle’s epochal drug film Trainspotting. The perfect pairing of Underworld’s hard-charging, sublimely melodic beats with Hyde’s raving stream-of-consciousness monotone, “Slippy” became iconic for its time, and peaked at No. 2 on the U.K. charts, opening doors for Hyde and Smith that they had never dreamed of in the previous 15 years.

But it was success Underworld never asked for, and which they struggled to reconcile with their often counter-commercial impulses. Although their previous two albums, 1993’s Dubnobasswithmyheadman and 1996’s Second Toughest in the Infants, were spellbinding works that coherently skipped from cathartic dance-floor euphoria to ambient sonic wash to supreme downtempo chill (often within the same track), further releases were increasingly fragmented in their presentation and dispassionate in their delivery.

Emerson left the group after 1999’s sporadically brilliant Beaucoup Fish, and future albums were never as compelling in full, as Smith and Hyde’s relationship began to fray and both members found more of their artistic energy being funneled into solo projects and other collaborations — including work scoring films and theater productions, and even soundtracking the opening ceremonies of the 2012 London Olympics, again under the direction of Danny Boyle.

But with the fast-approaching March 18 Astralwerks release of Underworld’s ninth album, Barbara Barbara, we face a shining future, the duo return more invested and inspired than they have been in decades. Kicking off their first LP in six years with the thunderous two-chord post-everything hypnosis of “I Exhale,” the album sidewinds its way through flamenco-tinged guitar instrumentals (“Santiago Cuatro”) and synth-pop exaltations (“Nylon Strung”) with a recaptured urgency and joyousness only occasionally present in their other 21st-century works. SPIN recently spoke with co-founder Karl Hyde over the phone about the many twists and turns of Underworld’s 35-plus-year career leading up to Barbara Barabra. Read that conversation, which has been condensed and edited for clarity, below.

Looking at the early days of Underworld when you guys were still in Mk1, and even as far back as the Freur days, are there any countries that you guys tour where that’s still the version of Underworld that’s most familiar? You guys did have some hits in some areas with those songs.

There are some places where people still remember things that you did in the early days. In Italy, we had a number-one hit with Freur, with “Doot Doot,” and in Australia we had a hit with “Underneath the Radar.” But, you know… that’s another lifetime, really, several lifetimes. When I went out [on tour in 2013] with my solo album [Edgeland], I took my own band out, and we played “Doot Doot.” It’s the only song I feel proud of, from the ’80s. Everything else became subverted, or pastiche, or something else that was getting on at the time.

What we loved was dub and electronics. Every time we got dropped from a record deal, we would revert to our first love, which was making these scapes, atmospheres. Electronics, fused with guitars, and voices, and film music would come in there as well. But nobody got it, really, and that’s why we had to keep subverting what we did, and watering it down, to get a deal. To kind of look at what was on the charts, and copying it. And it wasn’t something that we could sustain, because it was disingenuous, really.

So what was your and Rick’s relationship like the relationship that you and Rick had to underground dance music of the time of Underworld Mk1? Were you guys clued into what was happening in places like Chicago and Detroit?

Never knew anything about it at all. It was bizarre.

We heard populist electronics on pop radio, stuff like the Human League and Soft Cell, Heaven 17… obviously Kraftwerk. When we played Autobahn [as kids], that was something from another planet, a magical planet that we had no idea how to get to. But you know, for us, it was either electronic music that was in the pop charts, or there was the more left-of-center, esoteric, underground sound that [BBC Radio 1 DJ] John Peel was playing. And, we didn’t associate any of that with having a scene.

When we met up with [record label] Junior Boy’s Own and started working with them, we told them that to us, the 1980s had just been a nightmare, wasteland of a place. And then they told us that the 1980s were the really most fantastic, in terms of club music, telling us about this world that ran parallel to ours.

Do you remember one record that flipped the switch for you guys, something that made you understand this other world of dance music that was going on while you weren’t paying attention?

It was actually house on pirate radio. In the late ’80s, when we were making the second album [1989’s Change the Weather], we were hearing pirate radio. And the pirate radio stations were playing acid house.

Acid house, to me personally, was like the first time I had heard Tangerine Dream, the first time I had heard Hawkwind. These very long, soundscape-y, rhythm-driven, almost electronic orchestral pieces. And that’s what acid house sounded like to us, to me. It was like, “Oh my God, this is like the fruition of all the music I ever loved as a kid.” And it’s a massive movement.

And it’s underground, and yet it’s huge, it’s completely outside a culture. Revolutionary, really. Because it was self-sustaining, it didn’t need the music industry. It was pulling in tens of thousands of people. It was selling really large quantities of records, and yet, it wasn’t even showing up in the charts. It was fantastic.

[We] made a very impure sound. The purists all hated us, because we were so eclectic.

Did you guys get into the club culture at all, or did you feel like you were already misplaced from it by the time you got there?

Well, when we were making that second record, we went to see Adrian Sherwood. And it blew us away, mostly because of what Adrian did with the sound system… you know, turning off the highs and the mids and the lows, and kind of playing with the sound. He was using the sound system like an instrument.

Shortly after that, we were taken to our first rave, and that completely sealed it for us. Because there we were seeing an audience that wasn’t looking at the stage. There were no lights on the DJ, none at all, they were all on the audience. The audience was the main act. And then in other rooms, there were bumper-car rides, and different videos being played… it was like the ultimate Pink Floyd gig. And it just felt like we were completely on one side of it. I wanted to be part of it.

But it was Rick who had finally had enough, when we got dropped the last time [after Change the Weather] by Sire. He just said, “I can’t [be in this version of Underworld] anymore, I’ve got to follow my heart.” And that’s where he took us, very clearly, into clubland.

And that’s around when he was introduced to Darren Emerson, right?

Well, he went and found Darren [in 1990], yeah. I was out in the States, I was working for [former Berlin frontwoman] Terri Nunn, and we ended up going to Paisley Park, working there. And Rick was back here, trying to pay off our debt, because we had huge debt. Sire had, very kindly, given him some money to build a studio, and he salvaged what he could after paying off our debt.

He realized that if he was gonna make music that was acceptable to the dance floor, he was gonna need to work with somebody that understood it. And that was gonna have to be a DJ. So he asked around, and he was told about two people, one was an older, more experienced DJ, and one was this young kid. And he wisely went with the young kid. The young kid was making a bit of a name for himself, you know? And he lived just around the corner, and that was Darren Emerson.

What did Darren introduce you guys to, in a technical sense or in a larger cultural sense, that you weren’t already privy to?

What Darren started to introduce Rick to was the kind of music Darren was playing in his set. So Rick knew that he had to learn how to make [that] kind of music. Then, Rick wouldn’t need radio or press or any kind of promotion, wouldn’t need a record label, because Darren would be selling it by playing it in the clubs.

They experimented for a about a year. I was out in the States. I got into Debbie Harry’s backing band, for a big chunk of ‘91. Working with Debbie was extraordinary, she and [Blondie guitarist] Chris Stein treated me wonderfully. And gave me the opportunity to kind of wring the last of rock guitar out of me. I remember being in Los Angeles, and Stone Roses came on the TV. They were playing “Fools Gold.” Rick had played me “Fools Gold” back in the U.K., and I kind of got it. But when I heard it the second time, I knew it was the sound of my tribe, and I knew I had to go home. I had to be back in East London.

I came back and I was a singer who played guitar, I was a frontman. And I wanted to find a place in a culture that had no frontmen or frontwomen. No singers, no vocalists… definitely no guitars. So I had no place at all in the scene, and that was really scary. There was this young dude, Darren Emerson, who as a DJ was the new frontman. And there was no place for me.

But there was one album that stood out as being the blueprint for how I might be, and that was David Bowie’s [1977 album] Low. The way that the most iconic singer of all time, Ziggy Stardust and the Thin White Duke, stood behind the music, and threw his ego away, didn’t let it get in the way of allowing the music to do what it needed to do. And largely, he played a supporting role to what was going on. And so when it came to how I might begin to approach being a singer/frontman/guitarist in a genre which didn’t need them, it was to Bowie that I turned, as a blueprint for how I might approach it.

So when did things really come together for Underworld Mk2?

Well, it was a series of things. Our manager, Geoff Jukes, lent us some money to print 1,000 12-inches. Rick sold them out the back of the car, around all the DJ shops in London. And they all sold, people came back to us for more and we sold out. We were able to pay our manager back and have a few hundred quid profit. That had never, ever happened. We’d run up tens of thousands of pounds of debt with record labels — probably much more than that, in fact. And we made a profit, from our first-ever attempt at a 12-inch the clubs.

And we just started to make music. Like [1993 single] “Mmm…Skyscraper I Love You,” the lyrics of which I’d written when I was walking the streets of Lower Manhattan when I was over there with Debbie and Chris, recording together for a while. At night time, I’d just walk the streets, and these lyrics start to appear. And we recorded “Skyscraper,” and no one was interested. And the classic response of one very successful record label, he said, “If you’re gonna make this kind of music, get rid of the singer, and if you wanna keep the singer, get a drummer and have a real band.” [Laughs.] And what was great at that point was dance floors were filling with people who were dancing to the music Rick was making in the studio. So we knew these A&R people were completely out of check with reality.

And as luck would have it, there was a guy [we knew] who helped distribute the Thompson Twins’ 12-inches. [Twins frontman] Tom Bailey told us about this guy that promoted 12-inches, and this guy had promoted their first 12 inch, and it had done very well. So Rick and Darren had taken “Mmm…Skyscraper I Love You” to play for him and he said he didn’t really get it, he wasn’t interested. It just so happened that in the same office was Junior Boy’s Own, and [co-founder] Steven Hall, who called Darren afterwards and said, “I’ll put it out.” Didn’t need to change anything, so that was it.

When it came time to put dubnobasswithmyheadman together, did you guys ever second guess the way you balanced the club stompers with the more ambient pieces? Was there ever the thought, “Maybe we should just hit them with club track after club track”?

No, we simply followed our intuition. A curative, conglomerate of sounds and beats and grooves that Rick, Darren, and me liked. And the unlikely combination of people who made a very impure sound. The purists all hated us, because we were so eclectic. And at that time, no one was doing it to that extent.

At that time, we weren’t called Underworld either, we were just Rick, Darren, and Karl. And I didn’t want to ever make albums again, I didn’t want to be in a band ever again, didn’t want to tour ever again. And then one day, Rick on the quiet had been playing with Steven Hall of Junior Boy’s Own, and together they decided we had an album’s worth of material, and Rick created this assemblage that became quite an event. We were fortunate that we were working with people like Steve and JBO, and they encouraged us just to be ourselves.

I remember getting in a cab once, and the guy recognizes me, he said, “You’re the guy from Underworld. What went wrong?”

So when did you get the sense that people were starting to take to Underworld and to dubnobass? When did you feel like, “Alright, this is connecting with the people in a way we didn’t the first time around?”

It was a gradual build, every 12-inch that JBO put out of ours sold more than the previous one. One night, just after dubnobass had come out, we were playing Brixton Academy, an all-nighter there with [party crew] Megadog. And I nudged Rick and I said, “You’ve gotta look at the audience, you’ve gotta see what’s happening, we’ve never played for an audience like this.”

There were a few thousand people there. And what we saw was — it was like watching oil and water. There were two very distinctive tribes. One was the dance tribe that we expected, and the other this indie tribe. And you could see they were both looking at each other across the dance floor, as if to say, “Why are you here?”

It was like standing on the bridge, watching the banks of the rivers close up. It was unbelievable. Never saw it again, because after that it became normal.

So when it came time for you guys to do Second Toughest in the Infants in 1996, groups like the Prodigy and the Chemical Brothers were starting to get international traction and big beat was starting to become a thing. But you guys kind of went the other way with it — Second Toughest was a spacier album, almost a proggier album. Was that a conscious move, wanting to separate yourself from what the mainstream acts were doing?

Yeah. The problem about being part of a trend, or being at the vanguard of a trend is that you become attached to that trend. So that when the trend dies out, you die out with it. You’re perceived as belonging to it, and we never wanted to be part of any kind of trend. Whenever anyone said we were trance, or that we were techno, or started to give our sound a label, we deliberately introduced something that would cut across that… and would prevent us from probably being bigger at that time. But we didn’t want to be owned by labels, or any kind of convenient pigeonholing.

And it’s great, the Chems were signed to JBO just after we were, and they were some of our mates. And it was fantastic to see them do so well. The Prodigy, they’re half a mile from where we live, and it’s fantastic to see a band like that doing so well. They were doing well before all of us, anyway. Dance music is so expansive, there seemed no need to belong to any one aspect of it. Besides that, there was all this other music. There were so many genres to incorporate in our sound. To be kind of myopic, and to say, “We’re only focused on this one aspect of music,” that would’ve killed us. Just too boring.

Almost despite yourselves, you guys ended up having probably the biggest hit of that year, anyway. Were you surprised when Danny Boyle asked to use “Born Slippy .NUXX” for that final scene in Trainspotting?

Well [“Born Slippy”] had been our biggest-selling 12-inch, and we were happy it was done, and we were moving onto the next thing. And when Danny asked us if he could use that and “Dark Train” in Trainspotting, we refused because friends of ours had read Irvine Welsh’s book, and they expressed their enthusiasm for all the hedonistic aspects. And Rick and I were horrified, because we’d never seen our music as having anything to do with drug taking. What people do when they’re listening to their music is their business. We were never saying, “This is a waving flag for any kind of drug culture… any kind of mind-altering substance culture.” Music was enough to us.

So when Danny asked us, we immediately thought he must’ve meant in a film that was glorifying people getting messed up, and so we refused. And then he quite wisely understood what was going on, and arranged for us to have a screening of a few of the heavier scenes in the film. And once we’d seen those, it was pretty clear that he wasn’t glorifying drug taking at all — quite the opposite.

And we just gave him carte blanche after that. But even [then], JBO had to fight us to re-release the record. “Re-releasing is cheesy, we’re not gonna do it.” Steve of JBO had to canvas 100 DJs in Britain, and 99 of them came back and said, “Absolutely, re-release it.” Because whenever they played it the dance floor goes crazy, but people can’t buy it. And only one guy in our hometown of Cardiff said that it was rubbish. [Laughs.] We still think he was right.

And things changed… things weren’t such fun. Suddenly we were important to the industry. Of course doors opened to us, and we went from the second stage to starting to headline main stages. The money went up, our lifestyle went up, we could buy a nice house and a nice car. And it’s great, who wouldn’t want that after living on social security? It’s just that suddenly we were a band called Underworld, and we had a persona. And we had the weight of expectation on us. Not from our own team, not from JBO, not from our management. But you could feel it.

I remember getting in a cab once, and the guy recognizes me, he said, “You’re the guy from Underworld.” “Yeah.” “What went wrong?” Well, this guy just picked me up from one of the nicest houses in the area that we live in, with a brand-new car parked outside, and he’s asking me what went wrong. And I’m like, “What do you mean? What’s wrong?” “You know, all you had to do was write another ‘Born Slippy.’ You could’ve been the Prodigy.” I’m like, “Yeah, right.” And at that point I kind of knew that we were in a difficult place, because we’d been having a great time on the outside. And now suddenly we were on the inside.

Because of that song’s association with Trainspotting, which was kind of the Britpop movie of the time, did you feel like you guys were somehow lumped in with that scene?

Well, what’s interesting is… when people look back on that era, they see Britpop. The dance scene was much bigger than Britpop, but what people see is the acceptable face of contemporary music of that time. Which is traditional bands, with traditional frontmen who photograph well, who speak well, and who give good copy. And who write some cracking tunes, in a traditional way. We were part of a scene that was massive, but it was outside, uncontrollable, uncontainable. And often faceless as well. You know, how do you photograph a beat?

The Britpop bands were coming to all our gigs, were coming to the tent gigs… mainstream radio had to start playing people like us, because the groundswell was so massive, that to ignore bands like us and the Chems and Orbital would mean that popular radio was out of step with youth culture. So the great thing was that the scene almost forced it’s way into popular culture. It was an interesting time. Trainspotting and “Born Slippy,” they carved their own little space out in that time, I think. They’re synonymous now. And in a way, I think it’s like that culture’s Woodstock.

So when it came time to do Beaucoup Fish a couple of years after that, were you still reeling from the “Born Slippy” moment, or had enough time passed at that point that you had a clear slate and could just do what you want again?

I think then we went into years of being the band Underworld, and of touring, and then we could start to make another record, and… I think really those first two albums, dubnobass and Second Toughest, were my favorites in terms of entire albums, because they came from a time when we were cut loose from any kind of conception of being the band Underworld. And what the band Underworld does, and what the band Underworld is expected to do, and what the band Underworld should deliver.

And I think there were good tracks that came out [after that], there were good parts of albums that came out. Beaucoup Fish was our biggest-selling record. But… it felt, eh, some of the rough edges are coming off here, guys, y’know? And we’re getting a bit professional. And by that I mean less intuitive, and more streamlined.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”186441″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2016/03/underworld-karl-hyde-interview-300×133.jpg”]

After Darren left in 2000, do you feel like that’s now “Underworld Mk3”? Does it feel like a new iteration of Underworld, or is it still the same group that made those ’90s records?

Oh, definitely the same group. There was no Mk3. Rick had been at the core of everything — written most of the music, and the grooves, and Rick had produced those records. And Darren was, I think, less interested in the group and more interested in pursuing his own career, and his career as a DJ, and probably felt trapped by being in a band. It’s understandable. Nobody wanted him to leave, and we certainly could’ve found a way of accommodating anybody’s needs. It’s a shame. But no, it definitely felt like the same group.

Do you have a favorite of those first three 21st-century albums? One that you felt kind of got you back to the ethos of the first two albums?

No.

What do you attribute that to?

I think they were good in parts. Some tracks that we still play, and still enjoy playing. The more interesting thing that I think we were doing were the film scores, and then music for theater. Things outside of Underworld; they started to become the outlet for a less-conscious art.

Then in 2012, you guys got asked to score the opening ceremony of the Olympics. Did that get the old juices flowing again, or was that also…

No. No. No, no, no, no. [Laughs.] It did for Rick! We had come off the back of doing Sunshine with Danny [Boyle], doing Breaking and Entering with Anthony Mingella, and [2010]’s Barking had happened, and then we’d done [the score to Boyle’s production of] Frankenstein, and Frankenstein was fantastic because it was just three studios at the National Theater. We lived at the National Theater. We were part of rehearsals, and the forming of the play. It was so liberating: nothing to do with Underworld, but it had everything to do with our skills.

It was a tough time, you know; [my and Rick’s] relationship wasn’t good. It was very, very tense throughout the making of Frankenstein, but the results were really good. We’ve always said, “We’re not going to break up! Just because we don’t like each other, it doesn’t mean we’re going to break up!” Then Danny, amazingly, asks us to be musical directors of the Olympics. Without going into detail, mine and Rick’s relationship: It just kind of didn’t work. We weren’t getting the best out of each other, musically, by continuing to work together, and he very much wanted to do it on his own. I contributed some parts, but… It was the right thing to do, to let him do what he wanted to do.

I think [the new album] is the most genuine, honest piece of work we’ve ever done.

So, I went off and made a solo record, and put a new band together. Thus started a five- to six-year period where we were probably our most prolific, but we were working with other people, and finding other stuff out, which was really… It was a very healthy process, because we couldn’t feel stifled by being around each other. We couldn’t feel any kind of animosity toward each other by being held back or by being made to do something we didn’t want to do. Rick did an incredible job with the Olympics. And I went off and did something I truly believed in and wanted to do, which was a lot quieter, somewhere else, you know?

But gradually, what happened was… I wrote three albums totally improvising, and by the second album with Brian [Eno], it occurred to me that the person that I had done most of my improvising with was Rick — every night on stage we’d do improvising, and loved it, we always had a great time. And yet, we never made an album like that. As time went by, the person whom I’d had the most difficult relationship with — my partner — [was the] person I was really starting to miss. I missed my partner, and [felt] this strong desire to find out what would happen if you put the two of us together again.

So do you feel better about Barbara Barbara compared to the last few albums?

I think it’s the most genuine, honest piece of work we’ve ever done. It’s the right and proper thing to say, “Oh! It’s the best thing we’ve ever done!” I don’t know about that. But, all I know is that it’s the most honest piece of work that we have ever done, and it’s a genuine reflection of the energy between the two of us now. We’ve transcended all those difficulties.

Curiously, it was doing dubnobass [on tour in 2015] that did it. From day one of rehearsal for dubnobass, Rick and I, in a space of about a few hours, went from being polite to being relaxed to having fun to being blunt and direct with each other, and just looking forward to turning up to rehearsals. That dubnobass tour just sold out within days, and became the happiest tour of my life. We’d gone a long way — a long way away — from the dark days.

How did “I Exhale” come together? It’s kind of a new sound for you guys.

Before we made this record, Rick had said, “We’re not going to make this with software synths, we’re not going to make this with plugins, we’re going to make it with real equipment. We’re not going to start with anything.” He wasn’t going to turn up, like he traditionally did, with some beats or some music written, and say, “Here’s a starting point, Karl, do you think you can find some words for this?” He said, “We’re going to start with nothing. We’re going to write something new everyday, and then we’re going to move on. The next day we’re going to write something new.”

We spoke about words. Very often we’ll speak about words. He pointed to the photographs that I put out on the Internet everyday — “What’s going on there?” You know, I just take my camera, and my eye is attracted to something, and I kind of go “Snap.” “I like that… That’s how I think you should approach the lyrics this time.” Do exactly what I normally do: Sit in cafés, bars, walk the streets, but don’t think about stores, don’t think about what people are saying, don’t think about conversations that you overhear. Just, with your eye and your ear, capture smaller fragments of time, you know?

And we would turn up with our piles of equipment, like we did when we were kids. “What have you got today?” “Well, I’ve got this sound.” “That’s pretty cool! I like that! Well, I’ve got this sound!” “Well, that’s great! Let’s record it!” That’s where we would go, everyday. Just cut loose and be intuitive. For Rick, he had a plan. My plan was to completely forget about Underworld. Completely shut it out, and just be with my mate.

Where did the album title come from?

That was Rick’s father. Rick lost his father last year. Toward the end of his life, Rick’s father was talking to Rick’s mother — her name is Barbara — reassuring her that everything’s going to be okay. That they had a bright future. “Barbara, Barbara, we face a shining future.” To reassure her. When I heard Rick say that… I just said to him, “That’s the title.”

I don’t think he realized the extent to which I wasn’t going to back down. He came up with a few more titles, and I just sort of [responded,] “Are you mad? Why are you wasting your time talking to me about this? That’s the title!”

Obviously, dance music over the last five or six years has really taken off internationally. It’s almost become the default form of pop music, especially in the live, festival setting. Do you guys feel like you played a part in paving the way for that? Or do you feel like, “Well, we came out 20 years too early, because now we could be playing Vegas residencies for months on end”?

It’s funny: We talk about this sometimes. We were really lucky. We did really well. Our lives are pretty cool, thank you very much. What is interesting is in the ’90s we came up with a bunch of [other dance acts] and played the Organic festival, in [California]. It took a long time to take off, didn’t it? [Laughs.] It was a slow burner.

But it’s fantastic that it has taken off! I know some of the guys who were part of Electric Daisy were at that gig, in the ’90s. So you think, “Great, they took it and they ran with it!” I think it’s fantastic that the U.S. has got its own form of dance again, and that it’s massive, because of course that brings in a whole new generation of people who are into electronic music. Some of those start to look around, some of those start to look at the roots, some of those start to look outside of specific genres, and that’s good for everybody.

But what’s funny is, dance music, people have said that it’s only got a couple of years left… in ’95? It just keeps mutating, doesn’t it?