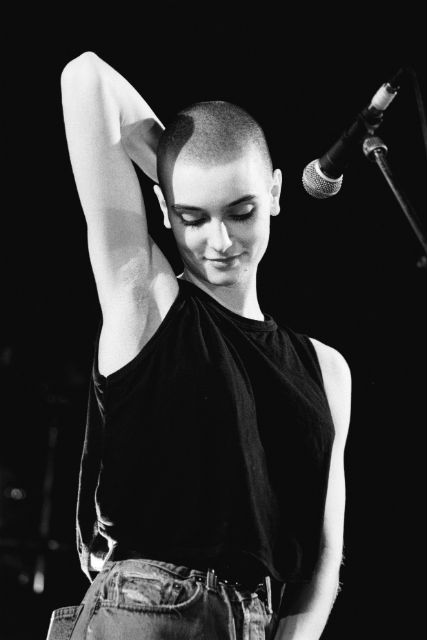

We were the first magazine in America by a long way to announce that Sinéad O’Connor was a great artist and was going to leave a big mark. She’s largely out of the public consciousness now but in the late ’80s and early ’90s she was a star on the same level as Madonna and Prince.

I discovered her — by which I mean I discovered her, not just “first listened to her” — working late one night and foraging in the wastepaper baskets of my editors for promo cassettes they had thrown out. I knew I’d hear about the music they liked, it was the music they didn’t like, or didn’t listen to, that I’d never hear about from them, so those were the tapes I’d play on my all-nighters. Most I too would chuck after one or two songs, some I’d listen to all the way through and make a note to follow up with a story or a review.

The Lion and The Cobra, Sinéad‘s remarkable, still-spine-tingling first record, I listened to over and over until five in the morning when, exhausted, I quit work and went home. I returned to the office around noon, still tired but excited to call the publicist, Elaine Shock, whose name was on the cassette, to see if it was still possible to get an interview with Sinéad, late as we must surely be to the party. She listened politely as I raved about the record, virtually begging her to let us have some access, and then there was an embarrassed silence, which I took to mean “How do I let this poor schlub down?”, but when she did respond, she said, “I sent those tapes out three weeks ago and you’re the only call I’ve gotten about her.”

We prophetically named her as one of the ten artists to watch for in 1988, in our end-of-the-year issue. It was the spark that got her attention — that much we will take credit for — but she shot into people’s hearts and souls like adrenaline. Her success was phenomenal and swift, none of it the result of gimmicky videos or clever marketing. It was all down to her magical voice and wonderful songs.

Also Read

30 Overlooked 1994 Albums Turning 30

A few years later, I told Elaine I wanted to interview her for the cover story of our issue guest edited by Amnesty International. Elaine said, enigmatically, that this might in fact be a good time for that. I flew to London to interview Sinéad in her manager’s office, on a sweltering day, rare for England then. There was no air conditioning and we had to close the window because of the noise outside, and in the sweat and airlessness and stench of the cigarettes she kept nervously smoking, we had what became more of an interrogation than an interview, as she revealed for the first time publicly that she had been sexually abused as a child, and that that had both gutted and fortified her as a young adult forging her way through life.

A few months later she tore up a picture of the Pope on Saturday Night Live and became — and has remained — a polarizing figure in pop culture, loved and hated, adored and reviled. I still think the world of her.

— Bob Guccione Jr., founder of SPIN, September 13, 2015

[This story was originally published in the November 1991 issue of SPIN. In honor of SPIN’s 30th anniversary, we’ve republished this piece as part of our ongoing “30 Years, 30 Stories” series.]

Days before the Grammy Awards last February, in the dark heart of the bombing of Baghdad, Sinéad O’Connor dropped a couple of her own bombshells: She was boycotting the Grammys in protest of the Gulf War and quitting the music business. The preposterous notion that anyone would particularly care is exactly what gave these pronouncements their weight. Sinéad’s conviction that these were significant responses to the war and the music industry’s apathy, made them so. They were reported — and discussed — worldwide.

Record sales alone don’t make Sinéad that important: the raw, unmeditated, genuineness of her rebellion does. She’s a spokesperson because she speaks. In today’s homogeneous, timid American society, that’s all it takes.

The previous August Sinéad had caused a tremendous stir by refusing to allow an arena to play the national anthem before her concert. The press rose like a mob to lynch her. Through the furor she protested she’d been misunderstood. and issued a carefully constructed press release trying to explain her position. In reality no explanation would have mattered to the war-frenzied mob. America was finally going to give itself amnesty for Vietnam and no head-shaved, Irish 23-year-old woman was going to interfere with that.

Unapologetic, Sinéad withdrew to London, where she lives, and studied acting. She says she’s going to play Joan of Arc in the planned movie. In July 1991 she released My Special Child, a four-song EP, donating the revenues to the International Red Cross Kurdish Relief program.

We met at her manager’s West London office, and talked in an insufferably hot conference room with the windows shut to keep the midday noise out. She thought it was going to be a three cigarette interview, laying them out neatly, side by side, in front of her like pencils. It turned out to be a nine cigarette interview.

When it was over, I played with her 4-year old son Jake while she went to make some phone calls. He kept kicking me — his idea of fun. I picked him up and held him by his ankles upside down over my shoulder — my idea of fun. “You smell pooey,” he announced shrilly. “You’ve got a lot of balls for someone upside down in midair,” I told him. Then I realized, that describes Sinéad perfectly.

SPIN: What made you want to do the My Special Child record?

O’Connor: I had written the song from my own experience. I wanted to put it out and use the money to raise awareness of child abuse. Then the Kurdish thing came up and seemed really urgent, so thought I’d do that. The song itself is about my experience with having had an abortion last year and how I dealt with that and how it made me feel.

SPIN: What made you want to get an abortion?

O’Connor: Well, I didn’t really want to. The pregnancy had been planned, and I was madly in love with the father of the child. However, things didn’t really work out between us. We were fighting. I was on tour, and I was feeling sick all the time. I didn’t know what to do, and he wasn’t really interested in the child. So I was left with the decision of whether or not to have the child, knowing that the father wasn’t going to be around. I decided that it was better not to and that I would have a child at a later stage when his father would be around and involved. I didn’t feel that I could handle it by myself.

SPIN: Did that trouble you deeply?

O’Connor: Yeah, because it was planned and I was very happy about it. I’d had three miscarriages previously, and I was quite worried about whether I was going to be able to hold on to the pregnancy and it looked like l was going to. So I was very distraught; it wasn’t a decision that I made lightly or that anyone makes lightly. It took me a year to get over it, but it was the right decision. I just believe that if a child is meant to be born it will be born. It doesn’t really matter whether you have an abortion or a miscarriage. The whole issue is pro-choice. I wouldn’t lobby for or against abortion, but I would lobby very strongly for the right of women to have control over their own bodies and make decisions for themselves. Nobody has the right to tell anyone else what to think or believe. Especially the Catholic church with the amount of murdering and pillaging that it’s done.

“The cause of all the world’s problems, as far as I’m concerned, is child abuse.”

SPIN: How much influence has growing up Catholic had on you?

O’Connor: It was never a really large part of my life. I always believed in God and the Virgin Mary and the immaculate conception and I love those things. So I just took from Catholicism what I loved about it, which was the image of her and all those sorts of stories. But I didn’t feel that it f–ked me up at all, I didn’t really take it that seriously. I just took from it what I liked and what made sense to me and what appealed to me. I would have had the beliefs that I have anyway.

SPIN: Do you believe in heaven and hell?

O’Connor: No, I don’t believe in heaven or hell. I don’t believe in any sort of burning. I don’t believe it’s right to teach children that God is somebody that will punish them if they misbehave, that God isn’t somebody who understands. That’s an abuse of children.

SPIN: Do you believe in heaven?

O’Connor: I believe in different levels of spiritual attainment and the highest level is something that somebody like Christ achieved. The highest level of spiritual attainment is the closest thing to heaven. But I don’t believe in heaven and hell as they’re depicted.

SPIN: You grew up in Ireland, surrounded by all this Catholic mythology.

O’Connor: I can sift off the bulls–t because there’s what’s called the church triumphant and the church militant. The church triumphant is basically God and the saints and everybody else, the church militant is the church on earth which I have no respect for.

SPIN: When you were growing up you were surrounded by great pain. Did you think that God had deserted you?

O’Connor: No, I believed in God very much. I didn’t believe there was anything to punish me or I didn’t believe I had been deserted. I always believed and prayed all the time and took great comfort particularly from the mother of God.

SPIN: Were you lonely as a child?

O’Connor: Yeah, I would say that I was, but I don’t think I knew that I was lonely. But I found it very difficult to speak to people. I just sat at the back of the class like this [hunches over], and that’s why my posture is so bad. I never spoke to anybody and I didn’t socialize. I didn’t know how to. I couldn’t up to a year ago even look a person in the face when I was talking to them.

SPIN: Why were you so shy, and how did you overcome it a year ago?

O’Connor: I forced myself to get over it, and I’m not particularly over it. But I forced myself because I couldn’t function and I just couldn’t continue to be that way. What made me that way was the abuse and the subsequent lack of assistance or understanding from anybody outside my home situation.

SPIN: What age are you talking about here? Eight years old?

O’Connor: Smaller than that even. If a child is being abused it will react in any number of different ways. What I did was I went into myself. I couldn’t communicate with anybody, I couldn’t study. I could read and write but I had no interest in it, I couldn’t get out of my own head.

SPIN: Were you physically terrified?

O’Connor: Yeah, I grew up in a state of terror, constantly. I’m one of millions of people who grew up in the same situation, who grew up terrified constantly.

SPIN: What did you think of? Did you fantasize about things that later became songs?

O’Connor: Yeah, I lived in a fantasy land, that’s how I survived.

SPIN: I grew up in a broken marriage, which was, thank God, not abusive. The family was very together. But I was effectively running the family at 15.

O’Connor: Well, that’s abuse.

SPIN: Yeah, but a mild form.

O’Connor: Well, what abuse constitutes is not allowing a child to be itself, not allowing a child to be a child.

SPIN: Don’t you think the real world does that anyway?

O’Connor: It shouldn’t.

SPIN: Well, in a perfect world it wouldn’t.

O’Connor: It can be a perfect world. The cause of all of the world’s problems, as far as I’m concerned, is child abuse. It’s the lack of understanding of children and of what they are and of the fact that they must be allowed to be themselves and form their own opinions and make decisions for themselves. From the moment a child is born, certainly in America and I think everywhere else, but it’s most obvious in America, the child is conditioned.

Everything that the child will see on the television or will learn in school or will hear on the radio or read in the magazines, or anything that it’s exposed to, is set out to form this child into a specific kind of person, one who doesn’t think for itself, one who doesn’t have opinions of its own and one who has no spirit of its own. From the time a child sets foot in school, it’s f–ked, as far as being itself is concerned. You may not ask questions, you may not have opinions of your own. You just learn what you’re taught in your history book, which is all lies, and that is what you must believe.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”162721″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/09/sinead-oconnor-19891-145×145.jpg”]

SPIN: Do you think that the media deprograms people?

O’Connor: I think it has been very cleverly employed to condition people. Certainly America is the most obvious example, although it’s the same all over the world. I think that television should be abolished completely. I think it’s completely destructive and there’s nothing positive about it, nothing at all.

SPIN: What about MTV?

O’Connor: It should be abolished.

SPIN: Why do you say that?

O’Connor: Because TV has killed free thinking. TV has killed art, it’s killed poetry, it’s killed theater it’s killed all those kinds of things. It conditions people; they just sit in front of it all day and believe what it tells them. Apart from that, purely from a scientific point of view — MTV being the worst example of this — if an image keeps changing really quickly your brain doesn’t learn to concentrate, and it gets so that you can’t concentrate because you get so used to seeing things only for a second that you don’t take in what you’re seeing. It’s not good for people who want to study or learn something.

We as a race have lost our spirituality. We’ve lost contact with who we are and what our purpose for existence is and we’ve lost contact with God. The reason for that is that we started going into other people’s countries and wiping out races and wiping out cultures in order to achieve, materially.

Through the loss of our spirituality, we feel empty. We have an enormous hole in ourselves and I don’t think that anyone can say that they don’t feel a huge emptiness in their lives, which they try to fill materially, because that is all they see on television or in the paper. They see that people who achieve materially are happy, so to fill their emptiness that’s what they go for. They go for drugs, they go for alcohol, they go for sex, they go for cigarettes, all to fill up the void. Never anywhere do they see any information telling them that they could fill it in another way. That if you have peace within yourselves, that you will attract peaceful things. You’re taught that you’ve got to go to work for a living. You’ve got to do a f–king job that you hate, just so that you can earn enough money to put food in your mouth and never will you discover who you are or what you can actually do.

The basic problem of the whole world is child abuse.

SPIN: That’s an incredibly sweeping definition.

O’Connor: If you look throughout history, all serial killers have been abused as children. All of them, without exception. All alcoholics have been abused as children. All drug addicts. All rapists. All sexual offenders have been abused as children. Hitler was an abused child; Saddam Hussein was an abused child.

SPIN: How did you get over it? You’ve got great strength and courage.

O’Connor: Well, the word courage means quite literally being afraid but going on. I’m still getting over it, but how I got over it was realizing that the cause was that nobody said anything about it. It was a continuing cycle — it’s a cycle of abuse. A child is abused, it never expresses itself because it’s never encouraged to express itself. It’s encouraged just to shut the f–k up. I realized there was an ongoing cycle. I realized that I was very, very f–ked up and that I had to do a lot of work on myself and that I had to go and get help.

SPIN: Did you see a therapist?

O’Connor: No. What I believe in most are the 12-step-groups — whether they’re Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous. There’s one that’s called Adult Children of Alcoholics/Dysfunctional Families, and that’s where I went.

SPIN: And that helped?

“Madonna, in an abusive way toward me, said that I was about as sexy as a venetian blind — the woman that America looks up to as a campaigner for women, slagging off another woman for not being sexy.”

O’Connor: Yeah, absolutely. It helps you to learn that it’s not your fault how f–ked up you are and everything else is not your fault. I keep thinking of the people that are in college in America, the people that would be around the same age as me, or younger, and I imagine that there are an awful lot of them who have experienced abuse of one kind or another. And I’m trying to explain it so that they will understand that you get to a stage where you just think you are a piece of s–t — that’s what it does to you, you think that you’re a piece of s–t. You think that you are worthless, you think you’re ugly. Every time you look in the mirror you just see an ugly wanker.

SPIN: Do you feel that way?

O’Connor: Yeah, I do.

SPIN: You’re incredibly beautiful.

O’Connor: I have no concept of that.

SPIN: But why not? I’m not the first guy that has said that.

O’Connor: It doesn’t matter what anyone says. I stand on stage maybe seven nights a week with five thousand people applauding me and telling me I’m wonderful, but it doesn’t make any difference to me, because I don’t love myself. Now I do, but up to that point I didn’t. It doesn’t matter who tells you you’re wonderful if you don’t think it and if your mother and father didn’t think it. You’re never going to think it unless you work on yourself and learn that you are lovable.

SPIN: What do you recommend to people who have been abused?

O’Connor: The first thing that I would say to those people is that I have felt exactly as I know those people feel. And you have to acknowledge, in the first place, that you have been affected and that you have every right to say, yes, you’ve been abused and you’ve been treated badly and unfairly. A lot of the time l felt if I talked about the abuse that I was making a big deal out of nothing, which of course is bulls–t. You think that you’ve no right to the feelings you feel because that’s what you’ve been told all your life. You’ve been beaten up for feeling the way you feel. So you start to build up a false self in order to please everybody, to make them like you.

I would say go to the 12-step groups or read the John Bradshaw-Alice Miller books. They are huge proponents of the adult-child syndrome, which is literally this — that if a child experiences something that’s very, very shocking and traumatic it will cut itself off from experiencing the thing consciously. Their brain cuts out because it’s too shocking for them so they only experience it subconsciously. They don’t feel anything. It can be scared by it, but it doesn’t know what it feels. And the feelings build up and build up and build up as you grow up. You are literally arrested at that stage of your development. You are three years of age walking around in a 50-year-old body. The world is being run by adult children.

It’s literally that you are living in here [indicates her torso] and you are this size [holds her hands two feet apart] and you are in a grown-up body. I used to have tantrums at twenty-one years of age, I used to behave like a 3-year-old child. I had no idea what I was doing. I used to look at myself and say, “What the f–k are you doing?” even while I would be doing it. Screaming and being upset and not being able to get out of bed, you know, just crying all day long, just really f–king angry, and wanting to just be a bitch to people. And I would have no control over myself. You are being controlled by your child. It is literally the puppet master. And you need to get in touch with it and to help it grow up. It’s terrified.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=JugUQJv9YlY

SPIN: What were your individual experiences?

O’Connor: I experienced abuse on every level that you can imagine. My mother was a very unhappy woman, who was very, very violent and found it very difficult to cope with life, because of obviously her own experiences as a child. I was beaten up very severely with every kind of implement you can imagine yourself being beaten with. And I was starved, I was locked in my room for days at a time without being fed, with no clothes. I was made to sleep in the garden of my house overnight. I lived for a summer in the garden of my house.

SPIN: How old were you?

O’Connor: At that stage, I was about 12. But earlier than that I had been made to sleep with my brothers and my sister in the garden and I had been starved, et cetera. And I had been psychologically abused by being told that I was a piece of s–t all my life, that it was my fault that my parents split up. That I was dirty, I was filthy, that I was kinky. I was, you know, basically a piece of s–t because I was a girl and that I was never any good.

SPIN: Were you the oldest?

O’Connor: No, my brother was the oldest. I was beaten up every single day and so were the others. Very, very badly. I lived my life in a state of terror. Merely the sounds of my mother’s feet on the hearth ceiling were enough to send us into spasms of complete terror. We were neglected, we were beaten, we were abused psychologically and emotionally.

SPIN: When did it stop?

O’Connor: When I left my mother, when I was 13. I want to point out that I have worked everything out with my family about this. And I love my mother and my father very much indeed. I’m not saying,”Bastards,” or “Woe is me” or all that stuff which is an important point for me to make for my family. But also for other people that it can be done.

I had always been encouraged to steal and one of the ways we made sure my mother didn’t beat us up was to come home with money and things like that, so myself and my sister stole. We never went to bed before two o’clock in the morning, we never did homework, so I never did well in school. I have no qualifications at all as a result of it, we were always sick, we were always completely f–ked up. So by the time I left, I didn’t know who the f–k I was or what I was doing. I had always been in trouble with the police for stealing. So when I went to live with my father, suddenly I had all this freedom and I didn’t know how to deal with it. So I started flunking out of school and still stealing. I got sent to this place called a rehabilitation center for girls with behavior problems. But at no stage was I rehabilitated or were any of the other girls. They were nice people, but nobody ever sat me down and worked with me in order to rehabilitate me back into society. And I was punished basically for being who I was again and rejected for being who I was again. For being what my parents had made me into, and what society had made my parents into.

It isn’t enough to take a child from its family. The parents of the children need help. It’s not enough to take their children from them or lock them up. The laws need to be changed as far as what can be done to help a child. The police used to come to our house on numerous occasions because the neighbors heard us screaming and they’d phone, and the police would come in and they’d just say, “Is everything alright?” and we’d be s–tting ourselves because we couldn’t say it wasn’t alright ’cause what the f–k were they going to do about it? Go back again and then we’d get the s–t kicked out of us if we said it wasn’t alright, so we’d just sit there and say, “Yeah, everything is fine.” And they’d go off again.

There’s nothing that the police can do, there should be more help from government for women with children. Women lose themselves when they have children. Women shouldn’t be told that they need to be in the home 24 hours a day, seven days a week because that’s just not right. A woman needs to be herself and have her own life. So governments should help with things like that.

I grew up being told that I was ugly, that my body was something to be ashamed of, that sex was something to be ashamed of and that if you liked it, you were like a slut, a piece of shit. And I was not told that sex was something that naturally happened between two people who really loved and understood each other. I was taught by the media that sex was something I could just do with anybody and that it was perfectly acceptable. I was told that by rock’n’roll as well.

SPIN: Was that appealing when rock’n’roll told you that?

O’Connor: Sex seems to be the only situation in which people can feel love. It’s the only place that they can feel intimacy so they go around doing it with everybody left, right, and center. And it doesn’t work. It just doesn’t work like that. That’s what we see so that’s what we go for. If we saw something else we might go for that.

SPIN: Did the church confuse you about sex?

O’Connor: As far as I’m concerned, the church has no right to open up its mouth about sex for these reasons. First of all, none of them ever have sex, at least they’re not supposed to. The second reason is that they do have sex. Priests in Ireland at the time of the abortion referendum were going around f–king young girls and getting them pregnant. I know of many instances. I know a woman who has been having an affair with a priest for the last 20 years. He has been a priest throughout the abortion referendum, the divorce referendum, et cetera. Now if she had become pregnant what would he have done? I know of another case of a priest who got a girl pregnant and made her go to London and have an abortion and met her back off the boat, looking at his watch to make sure he could get back in time for mass. At the time of the abortion referendum. They can’t f–king say a word about it, because they’re all shagging left, right and center and they can sue me for that but it’s the f–king truth. They should not open their mouths.

“I contemplated killing myself on numerous occasions. Because I just couldn’t see that there was any way out. But now it’s fine and we worked it out because we love each other and love is the thing that wins.”

SPIN: What about the way sex is portrayed in rap?

O’Connor: Of course, there’s sexism, but if you’re going to give out about it in black music then give the f–k out about it in white music, too. There are examples of it all over the place of appalling videos of women being abused. What about that “Cherry Pie” record with the video with the girl being hosed down? I mean, what’s that saying? What about “Love in an Elevator”? What’s that all about? Teaching people that they can just go and pick up some girl in an elevator and have sex with her?

SPIN: It’s all about fantasy, black or white. Rock’n’roll aims at being entertaining fantasy.

O’Connor: I don’t believe that rock’n’roll is all about entertainment.

SPIN: I don’t either, but it’s certainly an entertainment medium.

O’Connor: It has become purely an entertainment medium.

SPIN: It was always going to.

O’Connor: No, no it wasn’t. Look at the ’60s. Yeah, there was always entertainers and other people — communicators — and everyone got their records played. And then people began to realize that these people had far too much power and they stopped playing the records of the communicators. The entertainers are the ones that are pushed to the forefront, the ones that don’t really say anything about anything but they just write really nice songs that everyone enjoys, which are great, but the rest of us get pushed back. We don’t get our records played, we don’t win Grammys. We don’t win awards for our ability to…

SPIN: You get your records played.

O’Connor: I don’t. “Nothing Compares 2 U” got played. I never got a record played before that and I probably won’t get one played since.

SPIN: I think you will.

O’Connor: I don’t think so. It’s nothing to do with the audience. Because the audience only know what they hear and if they don’t hear everything then obviously they can’t form an opinion.

SPIN: Isn’t this a chicken-or-the-egg thing though? I mean the radio playlist and the MTV heavy-rotation list comes down to what the audience requests.

O’Connor: They request what they’re used to.

SPIN: Do you think England and America have become apathetic, sleepy societies?

O’Connor: We’ve been made sleepy. We’ve been made to not want anything, into a race that questions nothing. There is no concept of the evil that goes on, of the manipulation and the controlling. That everything they see has been fed to them in order to make them into a kind of person who will not question everything, who will fight for America, and think that they’re doing a f–king good thing.

SPIN: What did you think about the Gulf War?

O’Connor: I thought that it was despicable. I thought it was despicable because people were lied to and the truth will come out about that war.

SPIN: I thought it was disgusting because it wasn’t liberation we were reveling in, which was the one positive thing that came out of it.

O’Connor: That’s not why the war happened. Do you think America gave a shit about the people in Kuwait? What about what happened in Panama?

SPIN: Stay on Kuwait. The U.S. essentially encouraged Iraq to invade Kuwait, we know that for a fact, but what I’m getting at is that there wasn’t a celebration of the fact that brother mankind was liberated. It was a celebration that we beat the s–t out of somebody.

O’Connor: That’s what we’ve been made into. We’re quite willing for our own sons to be killed for that reason. We think that that’s a good thing. We don’t question. We don’t say, “Well, why is my son in Kuwait?” We say, “My son’s in Kuwait, isn’t it great?” That’s abuse of children. The fact that they’re selling to young children Gulf War stickers for their albums is disgusting. Completely disgusting. If all of the money they used on weapons was used for something constructive, was fed back into the earth, there is no reason in this day and age why every single person on this planet shouldn’t have enough to eat. Everyday in this world forty thousand children are starving to death, starving. Picture the image of your child starving to death. That’s happening to forty thousand women today. There is no need for that.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=dq2K4jHs92A

SPIN: When you refused to let the national anthem be played before your concert, very few people defended your position.

O’Connor: And nobody defended me during the Grammy thing which I will remember. Nobody. When the whole thing happened at the beginning of this year. No f–ker defended me, they’re all chickens–t. I’m talking about artists.

SPIN: I thought it was interesting that people, like FM DJs, who are normally the most left-wing liberals, who play records like “Ohio” on the anniversary of Kent state, and “Give Peace a Chance,” wanted to hang you.

O’Connor: That’s trendy though. South Africa is trendy, Neil Young is trendy. It’s safe.

SPIN: Why do you think people wanted to kick you out of the country?

O’Connor: Because I’m a girl, for a start. They would not be nearly as offended by it if I was a man. A woman with a shaved head who wears Doc Martens who doesn’t comply with what is expected of women, who hasn’t come through school and grown up to be what they wanted her to be, complaining about the American national anthem. They want to tell everyone that I’m civil.

SPIN: Looking back on the incident, would you do it differently?

O’Connor: No, absolutely not. I’m proud of it. Until my dying day I will be proud of that and of the Grammy thing. You know, put your f–king seatbelts on ’cause I haven’t finished yet.

SPIN: It’s rare today, Sinéad, to encounter that kind of stand-taking.

O’Connor: We have no spirituality, that’s what’s wrong. We have no sense of what the f–k we’re here for. We have no sense of — Jesus came here to show us that the truth was worth dying for. Jesus chose to be crucified, a most agonizing death and he s–t himself. Don’t let anybody say that he wasn’t afraid. He sweated blood. But he did that rather than say that what he was saying wasn’t the truth. And I believe that, and that’s what I took from religion was that Jesus came to show me that the truth was worth f–king dying for.

SPIN: What happens if your next record comes out and your record company says, “Sinéad, you’ve got to apologize for this anthem thing ’cause no one’s going to play it.”

O’Connor: I don’t give a s–t whether I never get played on the radio or not, ’cause I just do what I do for myself and my record company understands that. They’d be cutting off their noses to spite their faces — do you think they’re going to say that, for Christ’s sake, you know? And anyway, they’re not stupid. They know that I’m not one in a million. I’m merely expressing the feelings of millions of people. I just have a platform to air those views, and I’m operating for loads of people. I’m operating for all the abused children and all the women and all of the people who have been completely and utterly oppressed.

SPIN: Is there really a societal fear of women?

O’Connor: Yes, and that’s why women have been controlled. The women who are admired are the ones that have blond hair and big lips and wear red lipstick and wear short skirts, because that’s an acceptable image of a woman.

SPIN: Why?

O’Connor: Because it’s safe. It’s not threatening, it’s not intimidating. I’m threatening and I’m intimidating because I don’t conform to any of those things and I just say what I think. Madonna is probably the hugest model for women in America. There’s a woman who people look up to as being a woman who campaigns for women’s rights. A woman who, in an abusive way toward me, said that I looked l had a run in with a lawnmower and that I was about as sexy as a venetian blind. Now there’s the woman that America looks up to as being a campaigner for women, slagging off another woman for not being se??.

SPIN: What’s the answer for women? I mean, I don’t think you want to take that radical feminist….

O’Connor: No I’m not a feminist or an anything-ist. I’m just a humanist. I believe in human beings, and believe in God. And I live my life through the things that I believe. That’s all. I have a sense of why I’m on the earth, of where I go afterward.

SPIN: What drives you? What motivates you?

O’Connor: My belief in God motivates me.

SPIN: Do you see Jake as a manifestation of God?

O’Connor: Yeah, I do.

SPIN: When I first met you at SPIN one day, you struck me as very shy. Today you are certainly not shy, Do you feel that you turn the adversity in your life into fuel?

O’Connor: I don’t let the adversity stop me, And I know the truth; I’ve seen examples of the existence of the truth and the existence of God. The examples are everywhere. I know that the truth is worth fighting for and worth dying for. It’s worth anything. It’s like Keith Richards said about his problem with the authorities and drugs: “I don’t live by your petty rules.” And I don’t have to. And if there is anything I want to do, it is to show to everybody else that they don’t have to either.

SPIN: Do you think that you are a moral person?

O’Connor: Yeah, I am extremely moral.

SPIN: Do you think you are a good person?

O’Connor: Yeah, I’m trying to be good. I’m not a bad person. I do my best to be as good as I can be. Or, rather, I do my best to live by the word of God.

I think organized religion is a crutch. ‘Cause it’s controlling. Organized religion tells you what to think, what to believe, tells you who to be. I don’t believe in one Catholic church. I believe in every church. I believe in Buddhism. I believe in Hinduism. I believe in every religion. I believe you can take things from every religion. There is only one God. It’s just different interpretations and many different things to learn. You shouldn’t shut one out.

I used to lay in bed terrified at night thinking that I was going to burn in hell. It’s an abuse to tell a child that God sees everything and knows what you think about and that you are going to be burned in hell. It’s a huge abuse to teach children that God is not within themselves. That God is pollution. That God is bigger than them. That God is outside them. That is a lie. That’s what causes the emptiness of children.

SPIN: Which artists do you think give a damn about anything other than their own success?

O’Connor: I think that the hip-hop movement cares. It has its negative aspects —

SPIN: N.W.A. couldn’t give a damn.

O’Connor: N.W.A are relevant because they are speaking a truth. They are speaking about what life is like for some people. And if you don’t like what N.W.A are saying then you’ve got to find out why they are saying it. What makes young men grow up with those attitudes toward women? Child abuse.

SPIN: What about Public Enemy?

O’Connor: I think Public Enemy have done a hell amount of good. I think Professor Griff is a f–king madman. I think he is completely mental. But otherwise I think they’ve done a hell of a lot of good. The hip-hop movement, as far as I’m concerned, and the reggae movement have done so much good, more than I have ever experienced.

SPIN: It?s fascinating to hear you say that because rap takes such a beating because of the sexism elements.

“I think that television should be abolished completely. I think it’s completely destructive and there’s nothing positive about it, nothing at all.”

O’Connor: Why doesn’t heavy metal?

SPIN: Because it’s predominantly white, I guess.

O’Connor: Exactly. It’s alright for white men to be sexy. It’s not alright for black men t? be sexy. The second we as white women started to become attracted to black men that’s when the trouble started. The second we started thinking, “Oh, these are nice people,” that’s when the trouble started. They don’t want us having black men’s babies. They don’t want us understanding the black man and the black race.

SPIN: Everyone has to be careful not to buy their own bullshit? How do you achieve that?

O’Connor: I question myself ??nstantly. And because of my spiritual beliefs, I think it helps a lot of the time not to have a huge opinion of yourself. But because God knows if I’m being a f–king wanker.

SPIN: ??w do you handle celebrity?

O’Connor: You get used to it. I didn’t like it at all and there are aspects of it that I don’t like, but that’s what I’ve been given.

SPIN: Do you find that celebrity insulates you from the world?

O’Connor: You mean makes it so that I don’t necessarily know what life is like for other people?

SPIN: I mean that you’re not treated the same way as the average person is.

O’Connor: But I am an average person, and I am treated in the same way. I experience a lot of prejudice because of my look, because of who I am, what I am, and what I stand for. The same as everybody else.

SPIN: It’s because you intimidate people.

O’Connor: Not on purpose. They are intimidated by me because I don’t conform to what they expect because I have a shaved head, because I’m outspoken and direct. But if they are intimidated by that, it’s not my problem. I have to struggle with that, but I mustn’t lose myself in the struggle. I think one thing celebrity does, it’s provided me with a platform upon which and through which I can actually make a difference, to some extent. And that is what I intend to do.

SPIN: Do you feel alone?

O’Connor: No, n?, I don’t. I did feel very isolated, yeah. Because people have preconceived ideas about you and what kind of person you are.

SPIN: Are you working on any new music now?

O’Connor: No.

SPIN: Do you intend to in the near future?

O’Connor: Not for a long time, no.

SPIN: How long? A year?

O’Connor: I have no idea, but I have nothing left to say musically at the moment.

SPIN: I think, to a degree, people like your controversialness.

O’Connor: Far more than the media made it out to be. ‘Cause I never received an offensive letter from anybody. I’ve received hundreds and hundreds of letters of support from real people.

SPIN: How do you galvanize other artists to take as forceful a stand as you do?

O’Connor: You don’t. You just galvanize yourself. I gave up with other artists.

SPIN: You tried?

O’Connor: I expected other people to put their money where their mouths have been during the Grammys controversy. But now I give up. I’m just gonna do myself what I want to do, and they can all go and f–k themselves. Either they are with me or not; I don’t care. I think that if you look at the hip-hop movement, they are the only people that have fought for the truth in any way, and they are the ones who are probably the most browbeaten. It is easy to browbeat them because they are black.

SPIN: They are also intimidating and threatening.

O’Connor: Because they are black. Because you know that when you are in a room full of black people that they might have a right to have a problem with you.

SPIN: Who are your heroes today?

O’Connor: The black people are my heroes. Bob Marley is a huge hero of mine. I think that the African culture and the people who have fought for the survival of the African culture are my heroes and my role models. The Buddhists are my role models.

SPIN: Do you love easily? Is it easy for you to fall in love?

O’Connor: Oh yeah. It’s not easy for me to show love. It’s not easy for me to feel comfortable with the expression of either verbal or physical love because I’m — of course, I don’t know, self-conscious or I’m not so sure of myself.

SPIN: In child abuse, what part of it is, in your mind, unintended?

O’Connor: It’s all unintended.

SPIN: It’s all unintended?

O’Connor: It’s just adult children with their children. All of it was unintended.

SPIN: Did you ever talk to your mother about this?

O’Connor: No, my mother died long before I could talk to her about it, but I know that she knows what I think and how I feel. But I’ve spoken to my father a good bit about it. It’s all unintended.

SPIN: Was he aware of it going on?

O’Connor: Yeah, he was. And he did his level best; he did everything he could do, that he had the capacity to do. It’s all unintended.

SPIN: Did you in your heart of hearts wish he would have just come by with a van one night and taken you kids away?

O’Connor: Well, he did that, he did that. But we wanted our mother, too.

SPIN: You would rather go back?

O’Connor: Yeah, the thing is, instead of the children going to one parent or another parent, the parent needs help. You know, none of it is intended; that is the terrible, terrible sadness of it all. It’s just wasted lives, you know?

SPIN: Do you wish now you could talk to your mother? Do you wish she was sitting here right now?

O’Connor: No, because she and all the rest of us are better off with her being dead, to tell you the truth. I have a better relationship with her now that she is dead than I ever had with her when she was alive. I remember talking to her about it before she died and I said, “Why did you hit us? Why did you do that?” And she said, “I never did anything to you.” You know, she believed that she hadn’t done anything, because it was too shocking for her to deal with. Now, I know for a fact that she used to be really upset after she had done it because my father told me that she’d be devastated. I think that she had — and this is what my father thinks she had — this sort of predisposition to be unhappy. She had all the circumstances in her life by which she could have been happy. Like me. And she just couldn’t be happy. She couldn’t express herself, she couldn’t give love. You know, she must have experienced some kind of abuse when she was a child. She couldn’t express love at all. She just couldn’t cope. I love my mother. I’ve always loved my mother. I always understood that she didn’t mean to do what she did. I never hated her; I never had any grudge against her. I always understood that she was in a lot of pain and didn’t know what she was doing.

SPIN: Do you find your celebrity is a problem in your family?

O’Connor: Absolutely. It’s been a huge, huge source of awfulness. Because our family was so f–ked up anyway that it was easy to blame the f–ked-upness on me and the fact that I was famous and, really, my family couldn’t cope with it. And what they really thought, because they saw more of me in the papers than in the flesh, was that I didn’t give a s–t about anybody except myself.

I just got to the stage where I had a nervous breakdown at the beginning of this year, because I felt that I was sitting behind a wall and I could see out and nobody could see in and nobody could see me, and all around me were people saying to me that I didn’t give a s–t about anybody. Nobody just talks to you about the f–king weather and the price of eggs. And the rift that it caused me within my family made me want to kill myself. I contemplated killing myself on numerous occasions. Because I just couldn’t see that there was any way out. But now it’s fine and we worked it out because we love each other and love is the thing that wins. Luckily.

“I, along with millions and millions of other people, am the victim of a society which aspires to material success in order to fill the emptiness it feels.”

SPIN: Why would people say you only care about yourself?

O’Connor: Because I escaped. I escaped, that’s all. They were still there, and I escaped. I made my dreams come true. My dreams came true, and nobody else’s did. And I am a constant reminder to people that they are in pain. And when I talk about these kind of things in public it upsets people. ‘Cause everybody likes to brush everything under the carpet.

SPIN: What dreams have not come true?

O’Connor: None. They are all happening.

SPIN: What about men?

O’Connor: I don’t dream about a man. I don’t dream about the things I was brought up to dream about. That’s all bulls–t, too. That’s child abuse, too. You are brought up to believe that a woman is not a complete woman unless she has found a man, et cetera, et cetera, and had children. That’s bollocks.

SPIN: You don’t feel that way? I don’t feel I’m complete without a woman.

O’Connor: No. I want to be complete by myself. You can be incomplete with a man. What I’m aiming for is to be a complete person. And if that means a man is with me, great, but I’m not complete because he’s with me.

SPIN: I understand that, but I mean it’s part of the human experience.

O’Connor: Yeah, it is. Of course I want some man to fall madly in love with me and I want to fall madly in love with him, but when it’s meant to be it will be and there is nothing I can do about it. In the meantime my dream is to discover myself.

Because I have no hair, people think I’m angry. And because I speak very directly and have one of those faces that sometimes doesn’t express what my feelings are or what my words are — I just look angry or pissed off. But I’m not. I’m an Irish woman. I invite anyone in America to go to Ireland and study Irish women. I am your average Irish woman, particularly your average Dublin woman. We’re hard women. We’re soft women, as well, but we are hard and we don’t f–k around. And we curse a lot.

SPIN: Now, what if you met a man and you fell in love with him and he fell in love with you, and he said, “I love you and adore you, but I saw this picture of you with a wig on and you looked great with hair. How about growing it out?

O’Connor: Then I’d realize he didn’t love me at all.

SPIN: No, maybe he really did. It’s not a trick question; I’m not trying to trick you.

O’Connor: Oh, no, no. I would just think, well, “You can just f–k off then.” I mean, if I want to grow my hair — which, in fact, I do want to grow my hair — that’s because I want to grow my hair and not because nobody else likes it.

SPIN: Is the intimidation bit somewhat your creation?

O’Connor: Nope.

SPIN: Are you sure?

O’Connor: Absolutely. It is not a conscious creation. It is because —

SPIN: An unconscious creation?

O’Connor: No! It’s because I like to wear certain clothes. It’s because I like to wear my hair in a certain way and I feel the same as everybody else. But everyone judges a book by its cover. I’ve always been abused for what I look like.

SPIN: Isn’t that why you cut your hair?

O’Connor: No. I just refuse to allow it to make me become something else.

SPIN: Do you wake up every day feeling like today you are going to have to defend your position in life?

O’Connor: I end up having to do that every day, yeah. In certain situations.

“Merely the sounds of my mother’s feet on the hearth ceiling were enough to send us into spasms of complete terror.”

SPIN: Do you want to go to the country for a long weekend and simply not have to deal with what Sinéad O’Connor has to deal with every day?

O’Connor: I deal with whatever God gives me to deal with. And I’m more than happy to do that.

SPIN: You really, sincerely believe that, don’t you?

O’Connor: Yeah. I don’t believe that God gives a person more than they can handle.

SPIN: Is the fact that you keep your head shaved — obviously a very conscious act — is that even subconsciously partly because you are a victim? Were a victim?

O’Connor: First of all, shaving my head to me was never a conscious thing. I was never making a statement. I just was bored one day and I wanted to shave my head, and that was literally all there was to it. I already had it shaved on the sides and it was about as far as I could go. I think fiddling with the hair is a huge subconscious statement, yeah. Yeah, I suppose it is a subconscious rejection of conformity and of the family and everything that the word “family” can mean. I’m growing it now.

SPIN: Do you have a sense of being a victim?

O’Connor: Yeah. I, along with millions and millions of other people, am the victim of a society which aspires to material success in order to fill the emptiness it feels. And as a result of that aspiring, causes a huge pain for people and which results in child abuse. And that’s what I’m a victim of, yeah. I’m the victim of a society that doesn’t believe in self-expression or fighting for the truth.

SPIN: What do you think is the future of rock’n’roll?

O’Connor: That’s very difficult. First of all, you cannot separate music from politics because music has always been the voice of the people. Whether you like the sound of it or not, that’s what it is. [Sighs.] God, I think that at the moment the music industry is a microcosm of the world at large. And you can see that in the music industry that its main goals are material and the artists’ main goals are material: celebrity, fame, money. That is what they are concerned with, and they drip it in their videos and that is what they say to everybody else. I would like to see that change.

SPIN: Hip-hop is doing it, really, more than anybody.

O’Connor: I don’t think they do it more than anybody. I think they do it the same amount as heavy metal videos do it.

SPIN: There’s more status-symbol ??nsciousness ?n h??-?o?.

O’Connor: Yeah, because the black people are the poorest people in America. And they don’t want to live in poverty, and they believe that if they achieve material success that is what it is all about and it just isn’t true. And it is an abuse for artists to continue perpetuating that belief.

SPIN: Do you think rock’n’roll has a viable future?

O’Connor: It has dilapidated. You turn on any radio station the world — all you’ll hear is crap. You’ll never hear a record. You’ll hear entertainment and some of it is very good. But you’ll never hear any conscious music. You’ll never hear anything that inspires you, that makes you think, that spins you off into a fantasy. You’ll never hear that. It has dilapidated.

SPIN: One last question: What’s the best Irish joke you’ve ever heard?

O’Connor: Why are Irish jokes so silly?

SPIN: I don’t know?

O’Connor: So the English can understand them.