Just a couple of weeks after the Dayton Peace Accord brought an end to war in the former Yugoslavia, I decided I wanted to go to Sarajevo to report on the young people who had survived the siege. They were the age of our readers and they more than anyone else would make the atrocious, humanity-defying war relatable.

In early February, having made some crucial contacts with some of the young fighters who defended Sarajevo, photographer Loren Haynes and I went.

Getting there then wasn’t that easy. We got ourselves to Zabgreb easily enough, but then had to make our way down the Croatian coast to Split by hitching a lift with a British relief organization, who then kindly, and bravely, drove us through the mountains into Sarajevo. There was only one road down into the bowl of the devastated city, and it was known to be targeted by Serb snipers, who hadn’t left the region yet.

Even though the war had ended, the hostility hadn’t abated and there were still Serbs who shot at, sometimes killing, Bosnians, U.N. troops, and foreign journalists. And one of the first things we discovered was that the people of Sarajevo, held hostage for several years in a city once considered one of Europe’s most beautiful, did not believe the war was over. They had heard about ceasefires before, and seen neighbors and families slaughtered as soon as they ventured into the streets, picked off by snipers a mile away.

Also Read

THE DAY THE MUSIC DIED

It turned out to be the final and abiding ceasefire in this war, and Sarajevo did, finally, come out into the light safely again, and begin to rebuild. This is the story of some of the young people who lived the unfathomable nightmare.

— Bob Guccione Jr., founder of SPIN, September 9, 2015

[This story was originally published in the August 1996 issue of SPIN. In honor of SPIN’s 30th anniversary, we’ve republished this piece as part of our ongoing “30 Years, 30 Stories” series.]

A little known fact about the war in the Balkans is that the Virgin Mary predicted it. In June, 1981, she appeared repeatedly to six children, now known as the Visionaries, in the hills of Medjugorje, in then Yugoslavia. She told them that Jesus was angry with the human race for its lack of love toward one another, and that the children should pray for peace and spread awareness of the need for more prayer in the world. Hundreds of other people saw visions, too — it was as if she became a regular around the village — but she spoke only to the children. When one asked why she had chosen them to communicate with, she answered: “I do not always choose the best!” giving what may be the first ever Divine backhanded compliment. She also told the children, “This place will be hell on earth in a few years.” Ten years to the day of the first vision, the war in the former Yugoslavia broke out.

Three of the Visionaries still receive daily visitations, at precisely 5:40 p.m., and one, Ivan, communes with her publicly. At the appointed time, he stands on a large gazebo-like platform behind the church built in the Virgin’s honor, and stares into the sky, motionless and silent, for about ten minutes until he mutters “Ode [She’s gone]).” Then he tells the Franciscan priests what she said and they type it in various languages and stick it on the wall at the back of the church. One priest puts it on the Internet.

Although the Vatican hasn’t designated Medjugorje an official Holy Place, God seems to have: Despite the fact the village is only 15 miles from the Bosnian border, and 20 miles from Mostar, where some of the fiercest fighting took place, there wasn’t a single casualty in Medjugorje during the war.

Photographer Loren Haynes and I stopped there on the way to Sarajevo. A quiet, serpentine street of souvenir shops and cafes faces the church like a patient gallery, harlequined in sun and shadow. The church sits alone on an immaculately clean plaza: tall, white facaded, it looks as if it’s going to fall on you, an illusion of the slightly clouded sky floating overhead. Inside it is spotless and bright and the vivid stained-glass windows show the Virgin, beatific, appearing to the children.

It was mid-evening and dark by the time we left Medjugorje. We were traveling with two Englishmen, Bill and Andy, who comprised the entirety of the Bosnia Aid Committee of Oxford (although at the height of the war, Bill led a convoy of trucks delivering 20 tons of aid into Bosnia every two days) and Feryal Gharahi, an Iranian-born Muslim and U.S.-based lawyer who had adopted BACO. We were headed to Bill’s house in Pazaric, a village in the mountains above Sarajevo, where we would stop for the night.

There are no rooms on the eighth floor of the hotel; they’ve all been blown away. Bullet and shrapnel holes pockmark the walls and doors. The carpets are bloodstained.

Loren and I sat in the back of the heatless van huddled under a blanket, frozen by a draft from the rear door which didn’t shut property. Earlier in the day through the rear window we saw the receding scenery of a war zone: a tank parked at a barren crossroad, soldiers in jeeps, rows of blown-up buildings, an old woman in black bent over in her garden, picking at the miserly earth like a huge crow. Now everything was black as we dipped and climbed and wound our way through the mountains. Occasionally, we’d see a car pass in the other direction, the red coals of its taillights shrinking in the dark. A huge convoy of military trucks and tanks groaned and rumbled past. At a checkpoint, Serb soldiers opened the back of the van and peered nervously in at us, but when we showed them our NATO press laminates, waved us away, bored.

When we got to the house, Bill’s landlord, Haris, and his wife, Ida, lit the stove in the dining room and made us tea, and Haris brought out a large glass jar of distilled alcohol called Loza to warm us up. Before the war he had been an electrician; during it he laid land mines. Now, post-war, he had to go pick them up again. Strangely, he was very cheery about this work. He told Bill and Andy the road to Sarajevo was open again, which meant we wouldn’t have to take the precarious route over Mount Igman in the morning, but snipers were firing at vehicles as they passed through Ilidza. He announced this breezily.

His face was creased like the palm of a laborer, and he spoke with one hand in front of his mouth, as if he were trying to keep his face on. He smoked and talked incessantly. Intermittently, Andy translated a portion of what he was saying. At one point, Haris jumped up and, gesturing to Loren and me, showed us the shrapnel hole in the wall by the sink where his wife had been standing when a shell hit. It must have missed her head by two inches. She chuckled delightedly as he retold the story.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”161796″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/09/sarajevo-snow-park-145×145.jpg”]

It snowed every day we were in Sarajevo. It would stop and start several times, giving us the impression of being in the city longer than the five days we were, by punctuating each one of them so distinctly. You’d walk through the soft falling snow, enter a place, come out an hour later and it would have stopped and the streets would glisten blackly and the sidewalks slosh grayly next to the perfect white carpets of the many small parks, whose trees had been cut down for firewood during the war. The few cars would shoosh through the thin layer of water, or splash through a puddle collected in a pothole created not by municipal neglect but shelling. The sun, in the leaden sky, oscillated between a much brighter and much darker gray, lighting and dimming the snowy streets and destroyed buildings whose charred facades were braided in thickened snow. You could see through their glassless windows into the hills behind, which ring Sarajevo like the terracing of a huge stadium. The other, still-intact buildings were soot-drenched at their bases where they met the mostly broken pavement. Their walls were darkened by patches of missing plaster and torn-away brick, and flecked with bullet and shrapnel holes like the black spots of an untreatable skin disease.

A tram, boldly red, rumbled past our hotel and down the middle of Marsala Tita, the main street which runs through the city as a bent spine. The tram is free and full of people.

The snow falls in long, fat flakes, further quieting the already quiet city. There are people walking over the thin, lumpy pillow of snow. There is no bustle anywhere, no rush hour, no rush. In hindsight it’s obvious there’s nothing to rush to, or particularly from. At the building the U.N. made its headquarters, the lighted offices a floor above the street gleam dully like jaundiced eyes beneath the brow of deepening evening. A small café on the corner of an alley is well lit and inside a couple of people, not together, read next to white china coffee cups.

There are a few clothing stores, with thin, uncomplicated window displays: a brown sweater on a plastic torso, a few ties and belts on the shelf. A woman’s clothing store boasts, dispassionately, a couple of unremarkable dresses and a blouse. The stores are closed most of the time. Purchases for household goods and food are made at little kiosks. There are no restaurants on the main street, they are tucked into the maze of side streets unfolding behind Marsala Tita, and they are coming back to life, like plants after a thaw. There are several cafés, bright and loud, invariably playing English and American pop music of the early ’70s, for some unfathomable reason.

NATO soldiers, and their trucks and tanks, are positioned everywhere. They stand patiently by their vehicles, at intersections and outside major buildings, projecting a solid efficiency and understated power. Some have sprigs of flora in their helmets, presumably as part of their camouflage uniforms. But it looks ridiculous, like the plumage of ceremonial guards, since there’s almost no foliage left in Sarajevo to blend into. The soldiers are friendly and mostly bored.

We stayed at the Holiday Inn. The entrance has been closed for years — it was too exposed to sniper fire — so you come and go through a simple door at the back. None of the rooms have windows you can see out of; where there was glass is now this opaque, heavy plastic that the U.N. has covered most of Bosnia’s serviceable orifices with. Many of the rooms don’t have rooms: You push open the door and behind it is just a bare floor and a gaping hole in the far wall, sometimes covered, sometimes not, with the ubiquitous plastic. There are no rooms on the eighth floor; they’ve all been blown away. Bullet and shrapnel holes pockmark the walls and doors. Curtains have bullet holes that look like cigarettes burns. The carpets are bloodstained.

The rooms ring the hollow center of the hotel, so that you can peer over the hallway railings and look into the cavernous lobby. The hallways are dimly lit by intermittent ceiling lights. Green exit signs glow in the receding dark at each bend of the corridor. The lobby is unheated and the two-story-high glass wall between it and the street is a patchwork of some remaining glass and the sheets of plastic shivering in the wind. The electricity went out regularly.

For its front office, the hotel administration resides glumly in a cage, with bulletproof glass from the counter to the ceiling. The hotel is actually a renegade. It broke away from the Holiday Inn chain when the war broke out and kept the name and, for press and military arriving on assignment from around the world, the fraud of legitimacy.

It is frozen at some mysterious point in time, like a watch stopped at the moment its face is broken. Pictures in the elevator show a glistening swimming pool, people eating in the patisserie, another elegant, sunny restaurant, and the casino, as if that was the way life was here just yesterday, or, more eerily, will resume tomorrow. Unconsciously apocalyptic, the digital clock-on-the-wall of the front office is stuck at 9999.

Alma Catal is 16 years old and has been interviewed dozens of times. She is elfin and cherubically radiant. Her hair pulled back accentuates her round face and, sucking on a straw buried deep in a glass of Coca-Cola, she is the only Sarajevan I met who looks younger than she is. She tells us she’s a dancer, saying it with the authority of someone declaring her profession. But there’s very little employment in recuperating Sarajevo, and she doesn’t actually mean she’s paid to dance. Dance is what she does — in clubs, with her friends, Indefatigably apparently, to hip-hop and techno. It’s her identity. It may even be her vocation, but Sarajevo is still too fractured to nurture the fragile concept of vocation.

She loves techno, disdains “alternative,” and abhors rock’n’roll, scrunching up her face as we name most new bands. She keeps asking me if I know the people in certain groups that I didn’t even know were groups.

She was 13 when the war started, and lived on the 15th floor of an apartment building exposed to Serbian fire. Her bedroom faced the mountains held by the Serb Nationalists — “the Chetniks,” as she and everyone else in Sarajevo refers to them. Mercifully, she and her family were out when the anti-tank bullets — the kind that penetrate the armor and explode inside and incinerate the crew — struck their apartment and burned it and everything in it to ash. In her excellent English, this little girl told us about how her parakeet had died in the fire, and how her father had explained (and I imagined him doing so tenderly as he stood in the smoldering ruins of their home) that the bird would’ve died from the smoke, not the flames, and therefore not in pain.

Yes, she had had friends who died. “My best friend, this boy, went to make a tape for me, to copy a tape I liked, and when he was in the shop, a grenade came and killed him and some others in the shop. He was there for many hours. Nobody could get him because of snipers. It was terrible. I loved him so much, he was my best friend, and he died trying to do me a favor.”

Alma is well-known in Sarajevo, because of her dancing and the amount of times she’s been on television, particularly in or in relation to Bill Carter’s stunning documentary Miss Sarajevo. Carter spent over two years in Sarajevo and, in addition to making this documentary, arranged for the famous satellite hookups from the besieged city to U2’s Zooropa concerts. Carter’s film chronicles, with emotional rawness, daily life and death in Sarajevo during the war. In one scene, he has to run the gauntlet of sniper fire in order to cross a road and park, and the jerky footage is of the road and approaching building he’s running toward, and the audio is his breathing and footsteps and the pops of rifle fire. The centerpiece of the movie, but not, despite its title, the point, is a local beauty pageant that crowns Miss Sarajevo 1993. The pageant was emblematic of the defiance of the Sarajevans to being cowed by the siege to stop living. Obviously, life couldn’t and didn’t go on as normal. but each trivial vestige of normalcy was a tiny triumph. At one point in the pageant, all the contestants, in swimsuits, unfurl a banner they stretch across the stage which says, in English, DON’T LET THEM KILL US. The women are smiling at the camera as they hold the banner.

“The pageant was so ironic it had to be in the movie, of course, but that’s not all the movie’s about,” Bill told me. Miss Sarajevo is Alma, he said. “It’s her irrepressible spirit that represents the hope of Sarajevo.” She figures prominently in the film, as de facto narrator, a bright, animated fairy, surrounded by her friends rendered mute by the language barrier while she explains, in a blended tone of innocence and detachment, the inexpressible horror of her world.

“I did see people get killed,” says Vlado Kavajic. “Not exact moment of death, but two seconds later you see the effect. I saw brains in the mud.”

Bill is broad-faced, with flashing, intense eyes that suddenly fix on you as if he has just seen something over your head or on the tip of your nose. He came to Sarajevo in March, 1993, 11 months after the fighting began, with an unclear purpose. The war galvanized his sense of purpose, and the documentary was born.

Not merely an observer, he helped in any way he could. He was distributing boxes of food at a children’s center a few days after his arrival when he saw his first “instance,” as he calls it: He had just handed a box to a six-year-old girl who was running back home across the open square with it, when a sniper blew her head off. Her headless body lay there for two days. No one could get to it because of the snipers.

“The whole time was a psychological f–k. They would shell for days and nights and then stop, for two days, and you’d think maybe it was over, and you’d start to come outside and people would walk around. Then there’d be one shell in a playground. Eleven kids dead — they knew kids couldn’t be kept inside. That wasn’t an accidental shell. That playground was targeted — someone said we’re going to kill 11 kids today.”

Ten thousand adults and 1,700 children were killed and more than 50,000 wounded in Sarajevo. Captain Claridge, an English officer in the IFOR (NATO’s Implementation Force) press office, told me this was the first war where civilians were the primary target. She told me about a man walking his three-year-old son in a stroller and a sniper shot the child in the head, rather than the father. Why? Because there was more horror, more residual terror in killing the child in front of his parent. She told me about a school of small children that operated every school day of the war, with thick drapes over the windows to thwart the snipers, until a rocket crashed through the window and killed everyone inside.

The siege itself was a protracted act of torture. The Serbs could have marched into the Bosnian capital, unimpeded, and occupied it in three days. But they chose not to; instead, for three and a half years, until NATO forced the end of the war, they tormented the Sarajevans like a bored cat toying with its captured mouse, trying to drive them collectively mad. Nor was the siege airtight: the Bosnian army built a tunnel under the airport through which troops, weapons, and black-market goods were shipped regularly, and refugees from villages came in and city dwellers left. This, too was part of Bosnian Serb president Radovan Karadzic’s tactic: He knew one of the surest ways to undermine a city is to flood it with refugees.

Still, I wondered why the Serbs hadn’t ultimately just gone in and taken the city. When I asked one of the American NATO officers, he shocked me with his answer: They didn’t want bad PR. How could that remotely be an issue, I argued, after all the atrocities the Serbs were known to have committed: the mass executions, the concentration and rape camps, and the complete obliteration of villages, all in the vile, unforgivable name of “ethnic cleansing”?

The American shrugged.

“They figured people’d forget about that. The Olympics were in Sarajevo. They knew nobody would ever forget if they took Sarajevo.”

At the outset of the war, the Serbs released their most psychotic criminals and mental patients, armed them, put them on the frontline, and told them to have a good time. The rape camps were one by-product, as were the torture and slaughter of unarmed Muslims.

Bill Carter told me this story: The grandparents of a friend of his lived in the Serb-held suburb of Grbavica. Even though they were Muslim, their neighbors protected them, but they couldn’t leave their apartment because the army would take it. So they never went out. Neighbors brought them food and water.

One day a Serb tank pulled right up to the front of the apartment building, and there was lots of shouting and banging in the apartment of a woman, a teacher, below. The grandparents felt sure the soldiers had come to kill them. They hugged, prayed, and waited for the end. The noise went on for an hour. Then it stopped and the soldiers got back in their tank and drove it away.

The old couple went downstairs, expecting there’d been a rape. They found the woman sitting calmly at her table, completely fine.

“She used to teach mentally retarded children,” Bill concluded. “The tank soldiers were her former pupils, and they were all freaked out — they didn’t know how to operate a tank or what they were doing — and came to see her so she could calm them down.”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”161818″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/09/old-man-italian-soldier-sarajevo-145×145.jpg”]

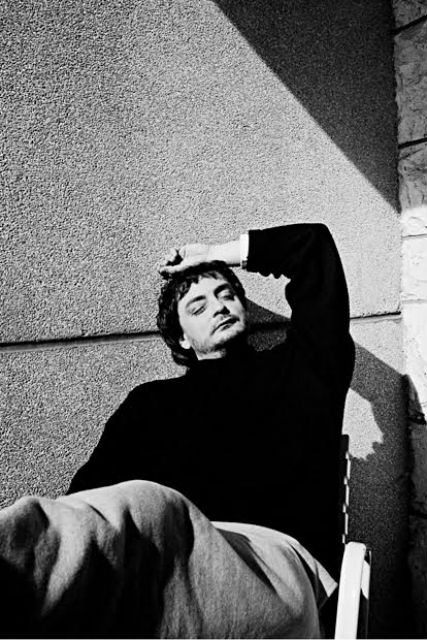

Vlado Kavajic is a musician, the guitarist and lead singer in a local band called Don Guido and the Missionaries. He is 33 — the age Christ was when he died, as he keeps hearing. He is trim and healthy-looking, with a high forehead, long jet-black hair to his slight shoulders and a Van Dyke mustache and goatee. His voice is deep and steady and he has a quick sense of humor. When he smiles his face creases with the pleasure.

He didn’t believe there’d be war, even though people kept asking him if he was prepared for it. When it came he went into the Bosnian Muslim army, even though he is Serbian. He fired a bazooka and estimates that he killed dozens of enemy soldiers. He played music right up until joining the army.

“I did see people get killed,” he says. “Not exact moment of death, because if a big bomb falls at the moment of explosion you can’t see much, but two seconds later you see the effect. I saw brains in the mud. I saw a man with a fountain of blood coming out of his neck, two meters away from me.” Incredibly, that man lived: Vlado held his hand over the wound, and carried him back to the camp. “He got paralyzed, but he can walk now.”

There were times when he was really scared. “I got terrified when I saw the death of my friends on the front line. It’s not an easy feeling, seeing death up close. I understand one thing, it’s part of life. It’s always there. If you come to terms with death, then you’re free to live.”

He was wounded only once: a ricocheted bullet hit him in the hand while he was playing pool at his base. He showed me the bullet, which he carries in his pocket. It is almost whole, just one side is flattened.

He says that the spirit of the people in Sarajevo during the siege was very powerful. “To be exposed to war constantly, every day, every moment of your life, to live four years under such conditions, if you don’t have a strong spirit, strong beliefs, a strong soul, you cannot survive, man. You either go crazy, or you die.”

He believes that Sarajevo is stronger because of that four-year nightmare: “Although it has been changed, it has been destroyed very much, enormous amounts of pain and misery happened to people, I think that now there is a different type of people, much wiser. A certain, maybe smaller circle of people really got wiser and maybe more determined to live.”

He thinks there is a good future for Sarajevans and, like so many of them, is forgiving of the aggressors, shrugging off holding a grudge, saying, “We who were attacked don’t want any more war.”

After lunch we went to the Trust Pub, a tiny bar with a pool table in front and several tables lining a banquette in the back. The band plays on a cramped loft platform.

He is late for rehearsal but the other band members, Fico the King, the bassist, and Attila the Hun, the drummer, are later, so we sit and drink coffee with Vlado and a few of his friends. I asked him how the war had changed his music. “I can really say it’s my music now,” he answered. “Maybe early it wasn’t really mine. The songs just come to me now. I make songs in a split second, no problem. I guess I became more open and more honest to myself also, and to others.”

“There’s so much romance in life now, for me. Much more beauty than before. You meet very nice women, very charming, and that is good.” He smiles. “It’s sometimes like in the movies, only more realistic.”

Trust, he said, in his voice that starts behind his chest, putting his hand on my shoulder, is very important. “And music — and love — are the most important things now. If you love, you don’t hate. It’s that simple.”

Suki says she doesn’t know why the war started. “Somebody told me, ‘You just can’t live together,’ and I don’t know why. We lived together before the war and it was great.”

Today was Bajram, the celebration of the end of the Muslim month of fasting, Ramadan. That night, the curfew was suspended and the bars and restaurants that normally turn you away at 10:00 because they must throw you out by 10:30 were able to stay open for as long as they wanted. The pub was packed till gone midnight, smoky, unbearably hot, pulsating with Vlado’s bluesy rock and the crowd’s dancing, as much as we could dance within the shoulder’s width space each of us occupied. At one point I had to pee. Having been to the tiny toilet earlier, when its single, overworked bowl was already much backed up, plumbing not yet one of the restored arts in Sarajevo, and guessing the situation couldn’t have improved since my last visit, I made my way outside. I didn’t realize how airless the pub was until I felt the sting of fresh air in my lungs. I crossed the street to the threadbare park, glistening blue-white in the street lamps lining it, and melting into a fathomless dark whose uneven crown was the outline of distant mountains.

I found a tree cloaked in shadow and relieved myself, listening to the muted sound of it striking the snow and looking back at the pub, lit like a lantern in the middle of a black, formless row of dead buildings. People milled in front, or walked by, a procession of unhurried shadows. Someone, 50 feet away, hailed a taxi coming down the hill by the side of the park. The taxi pulled onto Marsala Tita and stopped, waiting patiently under the moon of a street lamp, while its fares walked toward it.

I finished and came back down the slope, and waited at the curb as a couple of cars approached and passed, riding on the slush as if it were rails. The cold was biting and I was shivering now. In the club, I was sucked back into the heat and the stench of smoke and sweat.

After the pub closed, and its occupants spilled into the street, we went club-hopping. First we went to Cinema, Sarajevo’s upscale club, although all it is is a converted apartment that leads out to a large patio. It was literally too packed to move: You entered, went with the stream of people who had just entered before you, and were pushed from behind by the people entering after you. We did, as best I remember, a circuit of the two rooms and patio, and were carried back around to the front where, like silt, we were deposited against a wall, and stayed, happily, for about an hour.

We had swelled to a group of eight people, stuck to Vlado by his centrifugal force. We went from Cinema to a jazz club, where we drank until it closed at 2:00.

A Scotsman named Jim had joined us. He suggested we go to a speakeasy he knew in the hills. Even drunk l thought to myself hills will require a car, but while I was still logging this gem of logic in my mental vaults, Jim was procuring a U.N. van, and we were clambering into it from all sides. I was in the back, squeezed up against the door which I was fairly sure had been closed with less definiteness than I would have liked. Jim was driving, which is to say he was in the seat normally reserved for conscious, if not always sober, people who operate the vehicle — his version of which was to exhort it, in growls, including some ancient incantations about someone’s mother, perhaps his own, to climb the hill. Optionally, he tried steering, mostly to disappointing results. His discovery of the four-wheel-drive shift — there were, after all, two similar-looking sticks to choose from — was a great evolutionary step forward for our journey. As we skated sideways and backward actually more than forwards, I weakly inquired if this was in fact Jim’s U.N. van or the U.N.’s U.N. van, simply asking because it did seem he was on less than totally familiar terms with it and it had been a suspicious coincidence that this was the first vehicle we came across, as I recall. No one answered. Everybody was very happy (except me). Wedged into the corner of this van that still hadn’t abandoned its instinct to roll backward down the ice-glassy hill, I considered the growing likelihood that I had come all the way to Sarajevo just to die in the back of a stolen U.N. van, another drunk-driving victim.

Suddenly we stopped. Of our own volition. We had found the speakeasy! We emptied out of the van, our feet landing on crunchy, moonlit snow, trying to balance, gather ourselves and walk the ten feet or so to the front door, where, in a semicircle, grinning that half smile between looking foolish and attempting the look of all-knowing sophistication, we played the getting-in charade. We knock on their door at nearly three in the morning, and they pretend they don’t know what we’re talking about. as if otherwise it was perfectly fine to randomly call at their home in the middle of the night (when in fact, if you think about it, Sarajevo is exactly the last place in the world you want to go knocking on people’s doors at three in the morning if they don’t know you). Eventually, after a couple more exchanges in Serbo-Croat — presumably along the lines of “You sure you don’t have a speakeasy in there?” — we were admitted. We walked through a couple of rooms with people sitting on couches, talking quietly, into the kitchen where some very serious and equally drunk soldiers were sitting at a linoleum table, their rifles against the wall, and were taken into a neat living room, where we sat on couches and in armchairs, in the sort of orderly way you would if you were visiting your grandmother. We bought wine by the bottle, whiskeys by the glass, and two large bottles of mineral water. Jim made melodramatic toasts in his broad Scottish brogue that sounded like he was talking and drinking simultaneously, about friends who couldn’t be with us, and each time he and Vlado clinked glasses forcefully.

“De ye remember Dragan?” Jim asked Vlado at one point.

“Yes.”

“He jest p’id his speedin’ ticket the other dee—th’ one he got on Marsala Tita two years agoo.”

What ticket was this? I asked.

“He’s bombin dun Marsala Tita, being shot at by th’ Chetniks, and the focking Bosnia Police pull’im over. ‘Do ye know how fast ye were goin’? Yo were goin’ 95 miles per hour.’ ‘Nae I wasn’t’ ‘How fast d’ye think ye were goin’!’ ‘115 focking miles per hour!’ Th’ gave him a ticket. He said, ‘That’s why yer losing this war, th’ Serbs ‘ave got Kalashnikovs, and th’ Muslims have got ray-dar guns!'”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”161831″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/09/sarajevo-war-pub1-145×145.jpg”]

Since the day after Bajram was Ash Wednesday, I went to mass that afternoon. The church was old and freezing. Where the stained-glass windows would’ve been there was now only the opaque plastic. Everyone bunched together in the pews at the front, and we kept our coats, gloves, and hats on. Three priests in brightly colored ceremonial robes said the mass. In the first two pews to the right, eight women sang the hymns. Their beautiful voices rose to the stone eaves above them and hung in the vaults of the ceiling like smoke carried and dispersed by a breeze. I suddenly became overcome with emotion, moved by the simple, transcendent faith of these people who, after all they’d suffered, still believed God hadn’t deserted them, and I began to cry. I was kneeling and the women were singing and I kept my face hidden in my praying hands so no one could see my tears. I wasn’t ashamed, l just wanted to be unintrusive to my fellow worshipers and private in my own swirl of emotions. We lined up to receive the ashes and when I came before the priest and he applied the dark cross on my forehead, I realized that even though I couldn’t understand what he was saying in Serbo-Croat, I knew: We are dust and to dust we shall return, and I thought what an amazing place I was in to be reminded of that.

When I left the church it was a little after 5:00 and it was already dark. I hurried along Marsala Tita, past the chicken-bone intersection at Dure Dakovic that was the notorious Sniper Alloy. I was late to meet Suki at the Trust Pub to interview her. She had found Loren and me last night at the pub, latching onto us in the hope that we needed an interpreter.

The pub was too noisy, so we went to a café further down the street. There she told me she was 19 years old — l thought she was in her late 20s — and worked for the television station as a music assistant, matching music to programming and translating English-language movies into Serbo-Croat. She was paid a mere 90-deutsche marks ($60) a month with an additional 100 DM for each movie, but she was lucky if she got one a month of those to do. Which was why she was so eager to work for us at her declared rate of 150 DM a day. Her résumé was thin, she’d only interpreted once before as far as I could make out, but her English was good and knowing that two days’ pay equaled three months’ salary, it would have been selfish not to give it to her.

She is a pretty woman with intelligent, distrustful eyes, thick lips and a thick nose, and thick-brown hair to the nape of her neck, parted in the middle. She pursed her lips a lot when she talked, as if acknowledging and dismissing a thought at the same time. She sat back in her chair as she smoked, snaking her right-arm out to flick the ash into the ashtray. She smoked incessantly.

In her husky accent, she said she felt older than her age — “this is problem with war” — but that she doesn’t want to leave Sarajevo, because it’s evon harder to get work outside Bosnia, especially in Croatia, where they “hate Bosnians.” She herself doesn’t hate either Croatians or Serbs. “Why should I must hate someone if he is Serb, or Croatian? I mean, if he is good with me, I don’t care, be’lee me. I know one girl, she’s from Zagreb and she came here and she said, ‘You are great people, you don’t hate us, you don’t make jokes about us.'”

On the first day of the war, a rocket flew into her family’s living room. They had no idea why or, for the first seven days of the siege, what was happening.

“We just hear shouting all around. We are panicked. We was thinking, oh it will pass. All the time when war starts we are listening to the news, to the radio, and they didn’t know, they told us there are some Serbs on the street, they want some revenge [for a Serb killed at a wedding by a Muslim]. All television was lying. Serbian television talked like we are bad people, we killed all Serbs in Sarajevo.”

She says she doesn’t know why the war started. “Somebody told me, ‘You just can’t live together,’ and I don’t know why. We lived together before the war and it was great. When somebody told you a name, it don’t mean nothing to you. But now, when someone tells you a name, you just think, ‘Oh, he is Serb.’ But you don’t hate him for that.”

The siege preyed on Sarajevans like a Chinese water torture. “All the war, they are telling you it’s okay, it’s ceasefire, but they are shooting,” she remembers. “You walk in the middle of the street, really quiet, in the middle of the day, and you hear bullets and grenades, and you run home. You hear a million times that there is ceasefire, and they say it to move us into the street to kill us.” Like most Sarajevans, Suki lived on rice and beans, and sometimes feed, the dry grain given to farm animals. Meat was contraband: Every once in a while she’d be at a black marketer’s house who had meat, and offered it to her. Even though she was hungry, she’d decline it “on principle.” A kilo of sugar cost 100DM in the war. Some nights she’d dream of cookies and chocolate.

Suki spoke of going to hear bands in basements play by candlelight because there was no electricity. “You have a lot of best moments in war. Let’s say, one day you have sun, you are with people and you forget everything. That is a best moment, you know. You are drunk and you don’t think about nothing. You just want to forget about all that. You really have a great time. But tomorrow is another day.”

In the beginning, she thought the war was exciting, like being in a movie. She wanted to fight. Her brother who’s two years older became a soldier. But the novelty quickly wore off.

“I think Sarajevo will need a lot of time — no listen, Sarajevo will never be the same like before,” she says as she drags on her cigarette, the words coming out of the smoke. Around us other people are drinking coffee and beers. We could be in any café in any European city. “I didn’t blame Serbs for this — when I’m angry with somebody, when I want to kill somebody, you know, that somebody must do something to me. But how can I hate all Serbs? You have Serbs who are good people, be’lee me, and you just can’t blame them for this war.”

Her family lived in Grbavica at the beginning of the war; she was born and raised in that suburb. The Serbs took it over immediately and snipers who shot at Sniper Alley fired from what had been her apartment building. She recalled how, before the war, the soldiers used to play with her and her friends, show them their weapons, and tell them jokes. “We didn’t know they weren’t our soldiers.” she says now.

When she was a little girl, she asked her grandfather, who had fought in World War I (which started in Sarajevo), what it had been like. He replied it wasn’t interesting, saying, “What can I tell you?” and that he couldn’t explain. She says she could never understand that, but she does now.

We left to walk back to the hotel, to meet Loren for dinner. It had started to snow again, and the sidewalks were slippery. Suki put her arm in mine as we came to the intersection at Dure Dakovic and Marsala Tita and said, “Do you realize we are walking on the most dangerous street in the world right now?” I looked up at the flakes of snow falling and the snow-covered trees and the white park beyond the railings freshly trimmed white, and realized I didn’t.

“I will never forgive,” says Denis, “because I lost too many friends. In eight months, I lost ten people from my family. It’s not a thing you can forget.”

Oslobodjenje, Sarajevo’s newspaper, published every day of the war, despite its journalists being killed or wounded by snipers, its building being totally destroyed, having to move several times, and running so painfully short of paper that they sometimes printed only 300 copies of a two-page edition, which was posted in cafés and buildings so as many people as possible could read it. Paper donated from around the world was smuggled through the tunnel under the airport. As one of their chief editors, Mehmet Halicovic, told me, “Our people can live without bread, without milk, but they can’t live without newspaper.”

Today, Oslobodjenje (which means “liberation” and began publishing during the Second World War to oppose the Nazis) is housed in a small building on a square tucked in the folds of the streets behind Marsala Tita. Suki and I went to meet their editor and journalists.

There were about a dozen people in the “computer room” on the ground floor, where they make up the pages of what is now a 16-to-20-page edition, with a circulation of up to 7,000. A handful of operators sat behind long-outdated machines, several others sat on or stood around a couch in the middle of the room, smoking and drinking coffee poured from a large, copper Turkish pot. The room was cloudy with smoke. A small radio perched on a filing cabinet was playing George Michael’s “Jesus to a Child.” I noticed the curtains were closed over the large windows, even though it wasn’t sunny outside, and I asked Antonio, the journalist showing me around, why. “Memory,” he shrugged, meaning “habit,” left over from working during the war with snipers shooting whatever they could see.

Upstairs the offices are overcrowded but cheerful. Journalists without desk space sit in the hall in stiff-backed chairs, as if waiting outside a doctor’s office. Mehmet, who takes time to talk to me, despite having told Oslobodjenje‘s brave story hundreds of times, credited the foreign press stationed in Sarajevo with helping them with information, and talked about the illogical courage of his reporters getting so close to the fighting to report the news that literally meant life and death to their readers.

In one of the offices that seemed to comprise their newsroom, leaves from the newspaper were strewn around with manuscripts and faxes of foreign journals’ stories. I heard the long-forgotten sound of a typewriter as a worn-looking man with black hair combed over his baldness struck the keys. Here the culture journalist told me that one of the changes she’d noticed since the end of the war was young people weren’t listening to classical music as much, and she thought that was a shame. She also thought that the war had changed the “imagination” of people who wrote about culture. “Pain is a good inspiration,” she said.

From the newspaper we went to the market. I wanted to see where the notorious massacre had occurred which precipitated NATO bombing the Serb positions in the hills, which ended the siege of Sarajevo, and the war.

The market is much tinier than I imagined, about the size of a small parking lot. The rows of uniform, dark-green stalls are packed so tightly together they created the illusion of being under one roof. The narrow aisles are no wider than my shoulders. Hundreds of people were shopping on August 28, 1995, when two shells landed and exploded in the late morning, killing 37. Suki showed me the two shell holes, the larger one, about the size of a hubcap at the edge of the market, the smaller one in the middle. Around each hole was a splay of shrapnel holes, like many-toed claw marks. It was raining lightly and the large hole had collected a puddle. Rainwater dripped from the shiny edges of the stalls’ awnings.

Suki had been 100 meters away when the bomb hit. She described running to the market and being horrified by the carnage. Even despite all she’d seen, this rattled her to the core. She became emotional and began to shake as she told me, her voice rising like a frightened child’s, and for the first time I realized how young she really was. “It was terrible, all the blood and the screaming. The screaming was the worst. It couldn’t stop,” she said, staring down at the hole. Like everyone else who rushed to the market, she helped get the wounded treatment. Others took away the dead.

At the time, there was the suggestion, never completely dispelled, that the Bosnians had bombed their own market, but blamed the Serbs, to ignite such international outrage as to force NATO’s intervention. The Serbs denied they bombed the market. At any rate, two days later, NATO attacked, bombing Serb artillery and communications positions, and their tanks and bridges. They bombed relentlessly for three days, in almost Biblical fashion. The heavens opened up and retribution rained on the persecutors.

From the market I went, alone, to meet Denis, a Croatian who had defended Sarajevo. He was 17 and in high school before the war. He had a chance to go to a musical academy but the war derailed that. In April ’92, right at the outset of the siege, he volunteered for the Bosnian army.

Because he was young, his commanders positioned him in the hills as a sniper, away from the front lines. The first time he killed a Serb soldier he threw up. He said by the fourth time he killed, he liked it.

He is now 21, sitting opposite me in the narrow coffee bar, drinking a Coke. He is soft-spoken, but his voice, which is actually sweet and young while he talks, has a hard aftersound, a cold edge. His face is high cheeked and his forehead is high and flat. Long, shiny black hair falls away to either side of his face. He has a wide nose and his eyes are wide but black. They are probably dark brown, really, of course, but they look black, piercing but impenetrable, like onyx.

He had to kill soldiers in his own platoon. “This war is built on national hate, and in the beginning I had to kill the people who had aggression on my people, my town. Later on there were people who did not like me because I was not Muslim. In my squad, the people who are always with me, they love me, they respect me, like soldier. And they have nothing against my religion. But people from other units, they have something against that. When he pulled the gun, I must pull mine.”

I asked him how his experiences have changed him.

“I look how I was before — it not change me a bit,” he said. He feels that the people he fought and killed were not “his people,” they didn’t care about or accept him. He doesn’t forgive his enemies. “I will never forgive, because I lost too many friends. In eight months, I lost ten people from my family. It’s not a thing you can forget.”

“I can tolerate them. I can pass time with some man, and I know he was a soldier, and he came from the Serb side of Sarajevo, and maybe he killed, I don’t know, my uncle. If he don’t talk to me, if he don’t make contact with me, I will not react. But I cannot talk to them. I cannot be on the same level as them.”

His girlfriend, Delia, who is sitting with us, says she won’t forget the war, either. She’s younger than Denis and hosts her own television show, a program for children. “One of my shows, we talk about wishes, and one girl, four or five years old, I ask her what is her wish, and she said, “My wish is that my father come back to me.” Her father is dead. That girl will never forget. Me too, I will never forget.”

Denis got nightmares during the war, but not, he says, like the ones in books where you see the face of the man you’ve killed and your conscience haunts you. In Denis’s nightmares, his commander was always coming to his window and screaming to him to get ready, that they were under attack.

“This is funny,” he says, and smiles, and Delia lights up, too. “When NATO is bombing the Serbs’ positions around the city, I had a temperature. I was very sick, lying in bed, and I heard ‘blam, blam,’ and stood up looking for my rifle. ‘Oh, shit, where is it!’ And I tried to wake the person next to me, it’s my sister, but I think it’s my companion from the platoon, and I said, ‘C’mon, c’mon, we’re under attack.’ And I go to the living room and my parents are standing by the window and they are watching the bombing.”

He doesn’t think Sarajevo has much future. And if it does, he won’t be around anyway–he says he’s going to go somewhere else and try to live his life normally. He wants to go to California, but even though he plays in a band now, he doesn’t think he’ll be able to work as a musician in America, because there are too many professional musicians. He doesn’t believe the war changed his music, beyond giving it the benefit of his experience. “My music is not something the war can change,” he says flatly.

I asked him what the best moment of his life was. “When I buy my first electric guitar, just before the war. Then, when the war started, a grenade flew into my room and — there’s no more guitar!” He smiled again. “The best moment of my life, and then the saddest moment of my life.”

As we end the interview, Delia tells me she’d like to make a statement, but she’s worried about her grammar. I told her not to worry about her grammar, and she said: “When I was little girl, there were all kinds of churches and mosques in Sarajevo, all religion, and they were in 100 meters together, and everybody was tolerate of everybody else. That is my souvenir of Sarajevo, that is what I want to see happen again.”

There wasn’t much left of Ilidza. The roads were twisted into ruptured paving and cords of mud, with giant puddles dully marking the biggest shell holes.

In the taxi on the way to the ruins of the library, Suki told me a story about a Bosnian gangster who has risen to folk-hero status. “He was the first man in Sarajevo to pick up weapon — it was old army gun but it worked — and say we must defend ourselves, and we must kill the Serbs who try to destroy Sarajevo. He was the first and then others join him. He killed so many Serbs. I tell you, everybody was loved this man, bel’ee me.”

He was an incredibly fierce and brutal fighter, who could and did kill with his bare hands. He tortured some of his victims and severed the head of one of them. “But then he changed sides,” Suki continued, “and fought for the Serbs and killed Muslims on the front lines. The Serbs paid him more money. Everybody in Sarajevo was so disappointed.” I asked her what happened to him.

“I don’t know what happened to him.”

The library was the pride of Sarajevo, and acknowledged as one of the great ones of Europe for its renowned collection of antique texts and priceless books. Scholars from all over the world visited. The Serb Nationalists targeted it deliberately, to eradicate the Muslim heritage while they attempted to eradicate their race.

Only the walls and the carved stone columns, worn smooth by the ages so that the once intricate fine figures have been blunted to their crude essential shapes, still stand. The steps outside have been rounded by impacted ice. The inside staircases, because the windows and roof are gone, are slopes of ice.

We were alone while we were there, which was strange, as if time was momentarily suspended. It was snowing and soft flakes fell silently and slowly, like the souls of all the destroyed words returning to the library. While Loren took pictures, I made my way up to the second floor, slipping and falling as I climbed the slope on all fours. When I made it to the balcony, I looked down at a heap of red bricks on the ground floor covered with a layer of snow like freezer burn. Underfoot was rubble. I picked up a small stone and took my glove off to feel it in my hand. lt felt to me as if it had known life. as if even in its inanimateness it had possessed a consciousness of what it had been a part of. I thought about taking it as a souvenir, but that felt wrong, so I threw it down onto the pile of bricks, watching it hit, bounce, and then tumble into invisibility.

After lunch, we drove to Ilidza, a Serb-held suburb during the war. Like all the suburbs, it was being “reunified” and the Serb authorities were ceding control over to the Bosnian police as part of the Dayton peace agreement. The Serbs did not have to leave — in fact, they were being passionately entreated to stay — but they were, in droves, taking all their possessions they could carry away with them, sometimes just on their backs and in shopping bags. And they were burning the houses as they left so that returning Bosnians found only shells for what used to be their homes, one final indignity and loss in this unbearably cruel war. A European relief worker told me the departing Serbs were leaving new land mines behind (so perhaps there’s even more indignity and loss to come), which no NATO personnel would confirm officially, but several acknowledged off the record.

The first suburb, Vogosca, to be handed back to Bosnian jurisdiction was done so the week we were there. Ilidza was one of the next scheduled. Our driver, a tall, square-shouldered Muslim named Sacak, fought in the Bosnian army, doubtless with great courage (there wasn’t a lot of room in this war for people who didn’t have great courage), but adamantly didn’t want to drive us there. He offered to lend me his car instead, but told us he had to remove the license plates, because they would betray that the car belonged to a Muslim. I said that a car without plates might betray something not entirely on the up-and-up too, and that I didn’t fancy having to explain to Serbian police whose car it was once we’d established it wasn’t mine. Finally he relented — very bravely, far braver than I would’ve been in his position — to drive us to the edge of the suburb and we could walk the rest of the way in. His fear was palpable as we approached, he jabbed me in the arm to point out a distant clump of burnt-out houses: In the war, Serb snipers had shot at passing traffic from them. When we were stopped at an IFOR checkpoint. he pulled over and refused to drive any further, even though the soldier told us it was safe to proceed, and that at any rate we couldn’t stop here. Sacak drove forward 20 feet.

“He says the Chetniks will know he is a Muslim soldier and will kill him if he goes further,” Suki said to me, leaning forward over the front seat. Sacak was very frightened. We told him to wait for us at this spot and that we’d be back in an hour or two, and we got out and started to walk. We had only gone a hundred yards or so when an IFOR jeep picked us up and took us in.

Earlier that morning. I’d asked the New York Times reporter Stephen Kinzer what to be careful about in Ilidza. He said it was fairly safe, as long as you didn’t wander off the roads—the fields were still mined. “You want to get out of there before dark, because that’s when the snipers come out,” he added, matter-of-factly.

There wasn’t much left of Ilidza; it was mostly devastated. The roads were twisted into ruptured paving and cords of mud, with giant puddles dully marking the biggest shell holes. There was an open-air market, more spacious than the one in Sarajevo, but with only a few stalls active, and they were all selling mostly the same thing—the same chocolate bars, boxes of crackers, detergent, scraggly vegetables, soda, beer, some plain clothes. The merchants looked older and their clothes dirtier and more ragged than their counterparts in Sarajevo. They looked sadder, too—but then they were about to become voluntary refugees, whether genuinely fearful of retribution or stubbornly refusing to coexist with Bosnians.

We went into a café and could feel the tension toward us as physically as the sticky body heat and the low cloud of smoke. We sat ourselves, trying to project, if not exactly confidence, at least inoffensiveness. We asked for coffee, the waiter said we couldn’t have coffee, the electricity was out. We took Cokes, Loren whispered we should go, that this was dangerous for Suki, but she said no, we should stay, it might cause trouble if we went now. I felt the same thing–I wanted everyone to grow bored of hating us before we left, so that they wouldn’t particularly notice or care. The café was crowded and we had found a few of the last seats in the back. Most of the people were young and they were having fun. They were smoking and jabbing the air and laughing, and drinking coffee that must have been made before the electricity went out.

Back outside, I stopped two men walking and, through Suki, asked if I could talk to them. The one who did all the talking was full of anger—the Muslims did this, he said, waving his arm. They started this. And now we must leave our homes, but where can we go? This is our home but if we stay the Muslims will kill us when NATO leaves. He had a 12-year-old son, he told me, and he no longer wanted anything for himself, just his boy. Ho didn’t care for his own future, he just wanted his son to have a future. He pressed his finger into my chest. He didn’t want any more war, but he would kill anyone who tried to harm his son. He wouldn’t let Loren take a picture of him. As we finished, I told Suki to tell him thanks, and that I wished peace for him and his son. She translated this and his eyes watered and he took the hand I’d offered in both of his, and said in English, “Thank you.”

We talked to several others who each explained the war from their perspective, that it was they who lost everything and were being forced to evacuate, that the U.N. and America didn’t care about them. It was beginning to get dark. Suki negotiated with a taxi driver to take us back to the edge of Sarajevo, where Sacak was waiting and took us back to our hotel.

I asked Deniz if he ever found the war exciting. “Yes, in the beginning. But after maybe half a year I think, ‘When this stop?’ I want peace, but the peace isn’t come.”

Deniz Kamzic, the Holiday Inn’s only bellman, is sitting on the bed opposite mine in my hotel room. He was at the spot where the war started in Sarajevo, in the crowd upon whom the first shots were fired.

“You remember I tell you, I live in center here, by this hotel. On sixth of April I go with my parents to front of building where was our ex-government, in front of this hotel, and we are standing with many people. We are protest. We didn’t want the war, we wanted to live together. In one moment, the snipers started to shoot. They killed one girl on the bridge. It was sunny day. It was nice day. And we were so angry. We are seeing sniper shoot from this hotel, from Holiday Inn. People was crazy, and we broke in hotel. We throw rocks in window, and we go in hotel.

“I was in first group. We go first floor, and I heard automatic gun–oh, no, I don’t want to go in there! Our special forces tell us, go down, don’t go upstairs, the Chetniks will kill you. And we go down.”

“Did they get the snipers?”

“Yes. When I back on the street my mother’s looking for me. ‘Where are you?’ I was 16 years old.

“A couple of days from that date started real war. It started from the hills, and some buildings in Grbavica and Serb territories. They have modern weapons. We didn’t have good weapons, only some guns for hunting, pistols, and a couple of automatic weapons. And many young people, and my friends, are dying when this war started.”

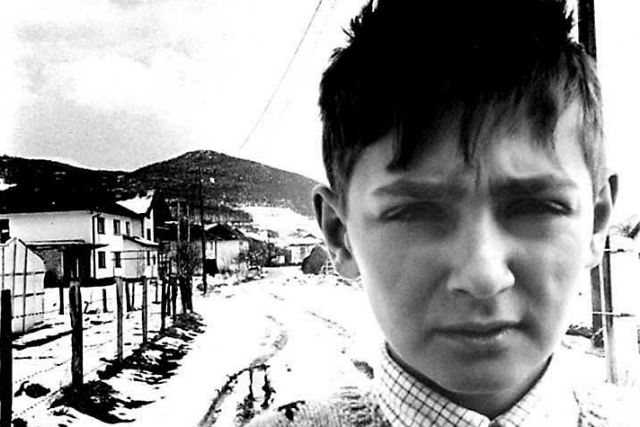

There was a deadly seriousness about him, blended with a contradictory exuberance. He frowned as he spoke, and sometimes smiled when he was finished. His eyes had a youthful light, but the features of his face were already advanced ten years beyond where they should be.

Before the war, he, too, had been in school, and intended to go to the air force’s military academy, which of course the war preempted. Since childhood it was his dream to fly. He joined the army in May ’93, when he was 17. His parents begged him not to. For six months he trained, ironically, to fire anti-aircraft guns. Then he was sent to the front line, in the bowl of hills that once provided the idyllic backdrop for the Olympics.

He thought he’d die many times. The most scared he was was when his commander sent him to another position on the front line, but the snow was falling so hard, he couldn’t see more than two meters in front of him and got lost. He thought the Chetniks would find him, but the gods spared Deniz Kamzic and his own soldiers picked him up.

I asked him if he ever found the war exciting.

“Yes, in the beginning. [Makes sound of shrapnel exploding and bullets whistling past.] When war started, everything was interesting for me, you know, but after maybe half a year I think, ‘When this stop?’ I want peace, but the peace isn’t come.”

“Did you kill anybody?”

“No.”

“Are you happy you didn’t?”

“Well, yes — because once I see dead peoples at the frontline, dead Chetniks. Our soldiers are bringing them in our base. I hadn’t seen death before and I think, I don’t blame him. Maybe he must come on Serb front line, and maybe not. Maybe the Serb government is call him and he must go to front line to fight to us. But if he is criminal, if he wants to kill, to rape, to burn houses, I would like to kill that man. That’s normal. Then I think, this man has a mother and she is thinking, ‘When will my son come home?’ But he will not come home because he is dead.”

He thinks it is likely that among the people he fought were some of his friends, boys he hung out with before the war, but he didn’t see any. He recalled, sadly, a Serb friend who fought with him, defending Sarajevo, who was killed. When I asked him if he coexisted with non-Muslims before the war, he replied: “Yes, of course, we live together and happy.”

What about ethnic hatred? “A couple of people on top,” he says with a frown. After four years, he stili doesn’t understand why it happened.

I ask if he can ever forget the war.

“Well, you ask a very hard question. But, yes, I have to, because I want to live together with some good people, who want to be civilIzed. And we young people are only hope for this country to live together. We must do something better, we must have some progress.”

[featuredStoryParallax id=”161840″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/09/Shadow-of-Peace-in-The-Park-sarajevo-145×145.jpg”]

Vlado had wanted us to come and hear him play at the pub again, and drink with him, as this was our last night in Sarajevo. But we were hungry and we went to have dinner instead with Deniz, Suki, and a couple of NATO press officers, one of whom told us about an American soldier who’d been shot by a sniper and just awarded the Purple Heart. Apparently, at first, it was thought he’d been shot in the wrist, a serious wound; in fact he’d been shot in the wrist watch, and didn’t have so much as a scratch on him. The original communique had been typed wrong. He still got the medal.

After dinner, we went to the pub and said goodbye to Vlado. As an afterthought, I asked him what he had done before the war. “I was a tour guide a Medjugorje.”

A handful of my damaged brain cells from the night at the speakeasy spontaneously reconnected and I remembered he had said something then about seeing the Madonna.

“Yes, I did see her,” he said. “It was Christmas day, 1990, around two o’clock. It was a nice sunny day. Me and several other tour guides were having lunch. A local guy was working outside his house, just across the road, and all of a sudden he stopped and was looking towards the Mountain of the Cross. He looked at me and said, ‘Vlado! Vlado! What’s there in the middle of the hill?’ And I looked over there and it was like a projection, like a laser-beam projection, just like she is pictured, with her left hand higher, the right hand lower, holy, holy, looking holy.”