This is the piece that (eventually) became the skeletal structure for Killing Yourself to Live, a book some people love and many people hate. The principal reason certain readers dislike that book is that they feel betrayed — they go into the process assuming it’s going to be about the locations where rock musicians died, and that’s not the point. Killing Yourself to Live is a memoir about all the spaces in between, and the relationship between the past and the present and the imagined. Thematically, it’s totally different from this original story, which is only about the places I visited (as opposed to how I got there). I remember this article as mostly straightforward journalism, except that the paragraphs are pretty long and I occasionally snort cocaine. — Chuck Klosterman, as taken from SPIN Greatest Hits: 25 Years of Heretics, Heroes, and the New Rock’n’Roll

[This story was originally published in the December 2003 issue of SPIN. In honor of SPIN’s 30th anniversary, we’ve republished this piece as part of our ongoing “30 Years, 30 Stories” series.]

Death is part of life. Generally, it’s the shortest part of life, usually occurring near the end. However, this is not necessarily true for rock stars; sometimes rock stars don’t start living until they die. I want to understand why that is. I want to find out why the greatest career move any musician can make is to stop breathing. I want to find out why plane crashes and drug overdoses and shotgun suicides turn long-haired guitar players into messianic prophets. I want to walk the blood-soaked streets of rock ‘n’ roll and chat with the survivors as they writhe in the gutter. This is my quest. Now, to do this, I will need a rental car.

Death rides a pale horse, but I shall merely ride a silver Ford Taurus. I will drive this beast 6,557 miles, guided by a mind-expanding global positioning system that speaks to me in a soothing female voice, vaguely reminiscent of Meredith Baxter. This voice tells me when I need to exit the freeway, how far I am from places like Missoula, and how to locate the nearest Cracker Barrel. I will drive down the eastern seaboard, across the Deep South, up the corn-covered spinal chord of the Midwest, and through the burning foothills of Montana, finally coming to rest on the cusp of the Pacific Ocean, underneath a bridge where Kurt Cobain never lived. In the course of this voyage, I will stand where 112 people have fallen, unwilling victims of rock’s glistening scythe. And this will teach me what I already know.

Also Read

Kurt Cobain Forever

Nancy Spungen: Stabbed To Death, 1978

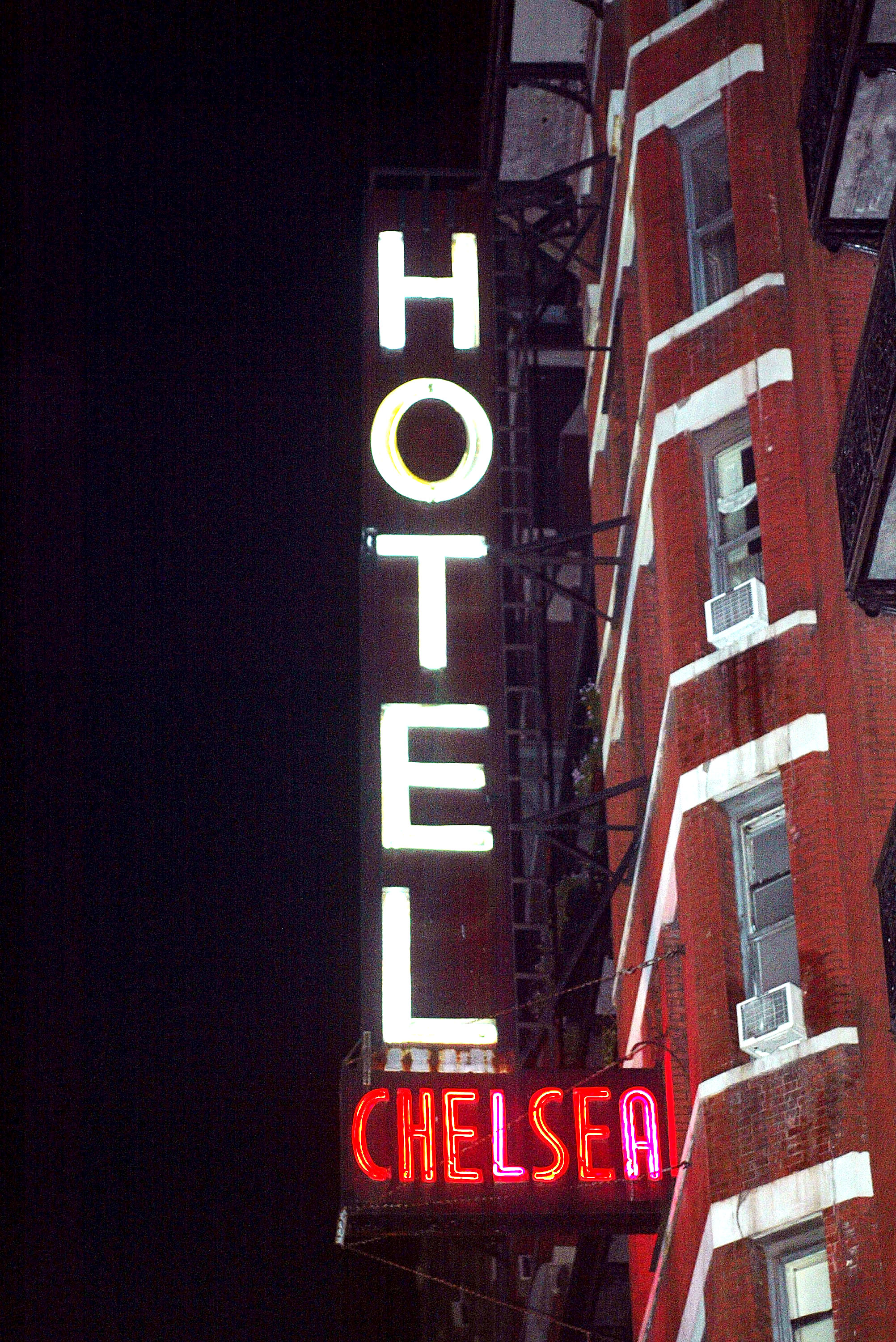

New York City (Wednesday, July 30, 3:46 p.m.): When I walk into the Hotel Chelsea, I can’t decide if this place is nicer or crappier than I anticipated. There are two men behind the reception desk: an older man with a beard and a younger man without a beard. I ask the bearded man if anyone is staying in room 100 and if I can see what it looks like.

“There is no room 100,” he responds. “They converted it into an apartment 18 years ago. But I know why you’re asking.”

For the next five minutes, these gentlemen and I have a conversation about drug-addled Sex Pistols bassist Sid Vicious, and mostly about the fact that he was an idiot. However, there are lots of people who disagree: Visitors constantly come to this hotel with the hope of staying in the same place where an unlikable opportunist named Nancy Spungen was stabbed to death. “We hate it when people ask about this,” says the younger employee. “Be sure you write that down: We hate it when people ask us about this.”

I ask the older man what kind of person aspires to stay in a hotel room that was once a crime scene.

“It tends to be younger people — the kind of people with colored hair,” he says. “But we did have one guy come all the way from Japan, only to discover that room 100 doesn’t even exist anymore. The thing is, Johnny Rotten was a musician; Sid Vicious was a loser. So maybe his fans want to be losers, too.”

While we are having this discussion, an unabashedly annoyed man interrupts us; his name is Stanley Bard, and he has been the manager of the Hotel Chelsea for more than 40 years. He does not want me talking to the hotel staff and orders me into his first-floor office. Bard is swarthy and serious, and he tells me I should not include the Hotel Chelsea in this article.

“I understand what you think you’re trying to do, but I do not want the Chelsea associated with this story,” says Bard, his arms crossed as he sits behind a cluttered wooden desk. “Sid Vicious didn’t die here. It was just his girlfriend, and she was of no consequence. The kind of person who wants to stay in room 100 is just a cultic follower. These are people who have nothing to do. If you want to understand what someone fascinated by Sid Vicious is looking for, go find those people. You will see that they are not serious-minded people. You will see that they are not trying to understand anything about death. They are looking for nothing.”

At this point, he politely tells me to leave the hotel. We shake hands, and that is what I do.

100 Great White Fans: Club Fire, 2003

West Warwick, Rhode Island (Saturday, August 2, 5:25 p.m.): For some reason, I assumed the plot of land where dozens of people burned to death during a rock concert would look like a parking lot. I thought it would be leveled and obliterated, with no sign of what happened on February 20, 2003, the night pyrotechnics from blues-metal dinosaurs Great White turned a club called the Station into a hell mouth. Small towns usually make sure their places of doom disappear. But not this town: In West Warwick, what used to be a tavern is now an ad hoc cemetery — which is the same role taverns play in most small towns, really, but not so obviously.

When I pull into the Station’s former parking area, I turn off my engine next to a red F-150 Ford pickup with two dudes inside. They get out, walk through a perimeter of primitive crosses that surround the ruins of the club, and sit on two folding chairs next to a pair of marble gravestones. They are James Farrell and his cousin Glenn Barnett; the two gravestones honor Farrell’s uncle, Tommy Barnett, and Tommy’s best friend, Jay Morton. The story they tell me is even worse than I would have expected: Farrell’s grandfather — Tommy’s father — suffered a stroke exactly seven days and five minutes after his son was burned alive.

I realize that this story must sound horribly sad, but it doesn’t seem that way when they tell it; Farrell and Barnett are both as happy as any two people I’ve ever met. Farrell is like a honey-gorged bear, and he reminds me of that guy who starred in The Tao of Steve. He’s wearing a tie-dyed shirt and a knee brace. He comes here every single day.

“I will remember the night this place burned down forever,” Farrell says. “I was in a titty bar in Florida — I was living in Largoat the time. I looked up at the ceiling, and I noticed it was black foam, just like this place was. And I suddenly knew something was wrong. I could just feel it. Then my mom called me, and she told me what happened. I moved up here to help out my grandma. She obviously has been through a lot, what with losing her son and then her husband. The doctor said my grandfather’s stroke was completely stress-related. I mean, he stroked out a week after the fire, almost to the very minute. That was fucking spooky.”

Farrell is 35, his uncle was just four years older, and they were more like brothers. Tommy, a longtime regular at the Station, didn’t even want to see Great White. He referred to them as “Not-So-Great White” and only went because someone gave him free tickets.

A few months after the accident, Farrell, Tommy’s daughter and his girlfriend, and two female strangers built all of the Station’s crosses in one night. The wood came from the club’s surviving floorboards. Originally, the crosses were left blank so anyone could come to the site, pick one, and decorate it however he or she saw fit. There are only about five unmarked crosses remaining, partially because some people have been memorialized multiple times accidentally.

[featuredStoryParallax id=”156252″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/08/150805-klosterman-quiet-145×145.jpg”]

As we talk, I find myself shocked by how jovial Farrell is.”I hide it pretty well,” he says. “And between you and me, I just did a line. Do you want to go do some blow?”

It turns out that this kind of behavior is not uncommon here: These grounds have fostered a community of both spirituality and decadence. Almost every night, mourners come to the Station cemetery to get high and talk about how they keep living in the wake of all this death.

“Nothing in West Warwick is the same,” Farrell says later, as he paints his uncle’s gravestone. “It changed everyone’s personality. Everybody immediately started to be friendlier. For weeks after that show, if you wore a concert T-shirt into a gas station, everybody acted real nice to you. If they knew you were a rocker or a head, they immediately treated you better. It’s that sense of community. It’s kind of like the drug culture.”

I ask him what he means.

“I mean, I just met you, but I would give you a ride anywhere in the whole god damn state of Rhode Island if you asked me, because I know you’re a good guy. I have something on you, and you have something on me. It’s like that here. The people who hang out here at night — it’s definitely a community of people dealing with the same shit. I call it ‘the fellowship.'”

A kid pulls into the parking lot and hauls an upright bass out of his vehicle; it’s one of those seven-foot monsters like the Stray Cats’ bassist used to play. He faces the grave markers, whips out a bow, and begins to play Eccles’ Sonata in G Minor. Either I am at the Station at the absolute perfect journalistic moment, or West Warwick is America’s new Twilight Zone.

“Oh, I used to play at this club all the time,” he says when I wander over. “I was in a band called Hawkins Rise, and I played upright bass through an amp. We were sort of like Zeppelin or the Who.” He tells me his name is Jeff Richardson, that he is a 24-year-old jazz fanatic, and that he knew five of the people who died here. He was vaguely familiar with many of the other 95.

“The same people came here every night,” Richardson says. “When a band like Great White or Warrant would come into town, all the same people would come out. There was never any pretentiousness at this club. You wouldn’t have to worry about some drunk guy yelling about how much your band sucked.”

To me, that’s what makes the Great White tragedy even sadder than it logically should be: One can safely assume that none of the 100 people who died were hanging out at the Station to be cool. These were blue-collar people trying unironically to experience rock ‘n’ roll that had meant something to their lives when they were teenagers.

Tonight, I will go back to the graveyard at 11 p.m., and lots of the deceased’s friends will pull up in Camaro IROC-Zs and Chevy Cavaliers. They’ll sit in the vortex of the crosses, smoking menthol cigarettes and marijuana, and they will talk about what happened that night. I will be told that the fire started during the first song (“Desert Moon,” off 1991’s Hooked). I will be told that the Station’s ceiling was only ten feet high and covered in synthetic foam and that when the foam ignited, it (supposedly) released cyanide into the air. I will be told it took exactly 58 seconds before the whole building became a fireball. I will be told that a few firemen at the scene compared it to seeing napalm dropped on villages in Vietnam, because that was the only other time they ever saw skin dripping off of bone.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=OOzfq9Egxeo

I will also be told (by just about everyone I speak to) that Great White vocalist Jack Russell is a coward and a hypocrite and that they will never forgive him (the fact that his bandmate Ty Longley also died in the blaze doesn’t seem to affect their opinion whatsoever). Around 1 a.m., Farrell will read me a poem about how much he despises Russell, and after he finishes, he will stare off into the night sky and say, “I would really like to hit him in the face.” But he won’t sound intimidating or vengeful when he says this — he will just sound profoundly sad. And it will strike me that this guy is a relentlessly sweet person with a heart like a mastodon, and I would completely trust him to drive me anywhere in the whole goddamn state of Rhode Island, even if he had never offered me drugs.

Three members of Lynyrd Skynyrd: Plane Crash, 1977

Magnolia, Mississippi (Wednesday, August 6, 8:20 p.m.): Despite the GPS, I’m semi-lost in rural Mississippi. And when I say “rural,” I mean rural: Ten minutes ago, I almost drove into a cow that had meandered onto the road. This is especially amusing because if I had driven into a cow, I would be only the second person in my immediate family to have done so. When my sister Teresa was in high school, she accidentally plowed into one with our father’s Chevy. Teresa hit it at 40 mph, and the old, sleepy-eyed ungulate went down like a tree struck by lightning. Those were good times.

I am hunting for the site of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s 1977 plane crash, which killed singer Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist Steve Gaines, and Gaines’ sister, backup singer Cassie. This tragedy is the presumed inspiration for the airplane scene in the film Almost Famous, although it’s a safe bet nobody on the Skynyrd plane came out of the closet just before they collided with the Mississippi dirt.

My initial plan was to ask for directions at the local Magnolia bar, but there doesn’t seem to be one. All I find are churches. Near the outskirts of town, I spy a gas station. The auburn-haired woman working behind the counter doesn’t know where the crash site is; however, there is a man buying a 12-pack of Bud Light, and he offers to help. “My old lady can probably tell you for certain,” he says. “She’s waiting in my pickup.” We walk out to his extended-cab 4×4 Ford, and his “old lady” (who looks about 25) instructs me to take the interstate south bound until I see a sign for West 568 and then follow that road for ten miles until I see some chicken coops. There’s one problem: There are a lot of god damn chicken coops in Mississippi. It’s getting dark, and I’m almost ready to give up. Then I see a sign by a driveway for Motefarms.com. This is the first time I’ve ever seen a farm that has its own website, so I suspect it’s more than just a chicken ranch. I’m right, and when I pull into the yard, I’m immediately greeted by a shirtless fellow on a Kodiak four-wheeler.

John Daniel Mote is the 21-year-old son of the farm’s owner. He is a remarkably handsome dude; he looks and talks like a young John Schneider, patiently waiting for Tom Wopat to get back from the Boar’s Nest. “This is the right place,” he says. “Follow me.” We drive down a dirt road behind the chicken coops. I can hear the underbrush rubbing against the bottom of the Taurus, and it sounds like John Bonham’s drum fills from “Achilles Last Stand.”

He finally leads me to a landmark that his father constructed years ago. It’s dominated by an archway with Free Bird painted across the top. There is a Confederate flag, of course, and a statue of an eagle. Mote says that if I were to walk through the Free Bird arch and 50 yards into the trees, I would find a tiny creek and some random airplane debris. I start to walk in that direction. He immediately stops me. “You don’t want to go in there,” he says. I ask him why. “Snakes. Cottonmouths. Very poisonous. Not a good idea.” And then young John Daniel Mote drives away.

By now, the sky is as dark as Nick Cave’s closet. I am surrounded by fireflies. There is heat lightning to the east. The temperature is easily 100 degrees. It feels like I’m trapped in the penultimate scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark, in which Indiana Jones and Marion are tied to a stake while the Nazis try to open the Ark of the Covenant. Or maybe I’m just thinking of that movie because Mote mentioned the snakes.

Still, part of me really wants to see where the plane went down. I feel like an idiot for having driven 547 miles in one day only to be stopped five first downs from pay dirt. I drive the Taurus up to the mouth of the arch and shine the high beams into the blackness. I open the driver’s side door and leave it a jar so that I can hear the radio. It’s playing “Round and Round” by Ratt. The headlights don’t help much; the trees swallow everything. I start to walk into the chasm. I don’t make it 50 yards. In fact, I don’t even make it 50 feet. I can’t see anything, and the cicadas are so loud that they drown out Ratt. I will not find the spot where Ronnie Van Zant was driven into the earth. I turn around, and the cottonmouth snakes gimme three steps toward the door.

Elvis Presley: Drug overdose 1977

Jeff Buckley: Drowned 1997

Memphis, Tennessee (Friday, August 8, 3:14 p.m.): So here is the big question: Is dying good for your career? Memphis offers two keypoints of investigation for rock ‘n’ roll forensic experts. The first is Graceland, where Elvis Presley overdosed while sitting on a toilet. The second is Mud Island, where the Wolf River meets the Mississippi. This is the spot where singer/songwriter Jeff Buckley went for a swim and never came back. One could argue that both artists have significantly benefited from dying: Presley’s life was already collapsing when he passed in 1977, so his death ended that slide and, in all likelihood, kept his legacy from becoming a sad joke (it is virtually impossible to imagine a “noble” 68-year-old Elvis, had Presley lived into the present). Meanwhile, Buckley’s death is precisely what turned him into a star. He was a well-regarded but unfamous avant-garde rock musician when he drowned on May 29, 1997. Almost instantly, he became a Christlike figure (and his 1994 album Grace evolved from “very good” to “totally classic”).

[featuredStoryParallax id=”156254″ thumb=”https://static.spin.com/files/2015/08/150805-klosterman-elvis-145×145.jpg”]

I am typing this paragraph while sitting by the banks of the Wolf River, presumably where Buckley disappeared into the depths. The water is green and calm as a sheet of ice. Buckley’s mother once insisted he was too strong a swimmer to die in these waters. I don’t know how I feel about this supposition, as I cannot swim at all (I can’t even float). The uber-placid river looks plenty deadly to me; as far as I’m concerned, it may as well be a river of hydrochloric acid.

But how or why Buckley died really doesn’t matter at this point; what matters is how his death is perceived by the world. And as far as I can tell, Buckley’s demise is viewed 100 percent positively, at least from an artistic standpoint. There is an entire cult of disciples (led, I believe, by Minnie Driver) who project the knowledge of Buckley’s death onto his work, and what they then hear on songs like “Drown in My Own Tears” is something that would not exist if he were alive. It’s a simple equation: Buckley is dead, so Grace is profound. But this says more about the people who like Buckley than it does about his music. Even when it’s an accident, dying somehow proves you weren’t kidding.

Robert Johnson: Sold Soul to Devil, 1930

Satan’s Crossroads (Friday, August 8, 4:33 p.m.): Just north of Clarksdale, Mississippi, at the intersection of Highways 61 and 49, the spirit of rock ‘n’ roll was spawned from Satan’s wheeling and dealing. You see, this is the “crossroads” where Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil in 1930, thereby accepting eternity in hell in exchange for the ability to play the guitar like no man before him. Satan’s overpriced guitar lesson became the blood of the blues — and, by extension, the building blocks of every hard-rock song ever written.

Obviously, this never actually happened. Robert Johnson (who was poisoned to death at 27) met the devil about as many times as Jimmy Page, King Diamond, and Marilyn Manson did, which is to say never. But this doesn’t mean rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t invented here. Rock ‘n’ roll is only superficially about guitar playing — it’s really about myth. And the fact that people still like to pretend a young black male could become Lucifer’s ninja on the back roads of Coahoma County (and then employ his demonic perversity through music) makes Johnson’s bargain as real as his talent.

Unfortunately, these present-day highways to hell don’t look like much. They look like (duh) two highways. There is spilled barley on the shoulder of each road, so this must be a thorough fare for local grain trucks. The only thing marking the site is a billboard promoting “microsurgical vasectomy reversal.” Ironically, I was able to find Robert Johnson’s crossroads with the Ford’s GPS: Somehow, it seems like satellite technology should not allow you to find the soul of America’s most organic art form. You’d think the devil would have at least blown up my transmission or something.

Cedar Rapids, Iowa (Saturday, August 9, 11:47 p.m.): Five hours ago, I was looking for a motel. Then I heard something on the radio waves of rural Iowa: 36 miles away, Great White were performing a benefit concert in Cedar Rapids to raise money for the Station Family Fund. Sometimes, you just get lucky.

After turning around and driving to Cedar Rapids, I realize I have no idea where this concert is, and the kind of bars that host Great White shows in 2003 are not exactly downtown establishments. I decide to just walk into a Handy Mart gas station and ask the kid working the Slushee machine if he knows where this show is. He does not. In fact, he hasn’t even heard about it. “Well, where do you think a band like Great White would play in Cedar Rapids?” I ask. He guesses the Cabo Sports Bar and Grill, a new place next to the shopping mall. And his guess is absolutely right.

The show is outside on the club’s sand volleyball courts; admission is $15. When I arrive, the opening band — Skin Candy — are doing a cover of Tesla’s “Modern Day Cowboy.” There are maybe 1,000 people waiting for Great White, and it’s a rough crowd. When you look into the eyes of this audience, you can see the hardness of these people’s lives. More than a few of them are complaining that the 16-ounce Budweisers cost $3.50. This is exactly what the crowd in West Warwick must have looked like.

I go backstage (which is really just the other side of the parking lot) and find Great White vocalist Jack Russell. He’s wearing a sleeveless T-shirt and pants with an inordinate number of zippers, and he’s got quite the little paunch. Somebody walks by and stealthily hands him some tablets, but it turns out they’re merely Halls cough drops.

I ask him what he remembers about the fire in Rhode Island, but he balks. “I can’t talk about any of that stuff, because there is an ongoing investigation, and I don’t want to interfere with anything the [Rhode Island] attorney general is doing.” This is understandable, but I ask him the question again. “Well, it changed my life. Of course it changed my life,” he says. “But I had to make a choice between sitting in my house and moping forever or doing the one thing I know how to do.”

Russell tells me he can’t discuss this any further. However, guitarist Mark Kendall is less reticent. He’s wearing Bono sunglasses and a black ‘do rag, and he fingers his ax throughout the duration of our conversation. He seems considerably less concerned about the attorney general. “That night was just really confusing,” Kendall says. “I was totally numb. I didn’t know what was going on. I had my sunglasses on, so I really couldn’t see what was happening.”

I tell him that there are people in Rhode Island who will never forgive him for what happened.

“Oh, I totally understand that,” Kendall says. “That is a completely understandable reaction on their behalf. I mean, I’ve never gotten over losing my grandfather, and he died 15 years ago. On the day of that show, I met five different people who ended up dying that night. I feel really, really bad about what happened. But no blame should be cast.”

I ask Kendall how Great White can donate the profits from their tour and still afford to live. “Well, we did sell over 12 million records,” he says with mild annoyance. Twenty minutes later, the band opens with “Lady Red Light,” and, much to my surprise, they sound pretty great. After the first song, Russell asks for 100 seconds of silence to commemorate the victims. It works for maybe a minute, but then some jackass standing in front of me holds up a Japanese import CD and screams, “Great White rules!”

Bob Stinson: Chronic Substance Abuse, 1995

Minneapolis (Monday, August 11, 1:30 p.m.): There are a lot of disenfranchised cool kids in downtown Minneapolis, and most of them have a general idea where Replacements guitarist Bob Stinson drank and drugged himself to death in February 1995. They all seem to think it was the 800 block of West Lake Street, near a bowling alley. They are correct. Stinson died in a dilapidated apartment above a leather shop and directly across the street from the Bryant-Lake Bowl.

I knock on the apartment door. No answer. I knock again. Again, no answer. This is strange, because I know for certain that somebody is in there. While outside, I saw a pudgy white arm ashing a cigarette out of the window. Granted, I don’t really have a plan here. I’m not exactly sure what I should ask this person if and when he or she opens the door. But I feel like I should at least see the inside of this apartment (or something), so I keep knocking. And knocking. I knock for ten minutes. No one ever comes out. I try to peep into the window where I witnessed “the cigarette incident,” but now the shade is down, and I’m starting to feel like a stalker. I decide to walk away, having learned zero about a dead musician I knew practically nothing about to begin with.

Kurt Cobain: Suicide, 1994

Seattle (Saturday, August 16, 2:12 p.m.): Lots of dead people here. If rock musicians were 15-ton ivory-bearing pachyderms, Seattle would be America’s elephant graveyard.

First, you have Mia Zapata of the Gits, the female punk whore presented liberation and self-reliance before she was raped by a sociopath and strangled to death with the string of her sweatshirt. There is Kristen Pfaff, the Hole bassist and smack addict who overdosed in her bathtub. And one cannot forget the (entirely predictable) demise of Alice in Chains singer Layne Staley, a man who OD’d in perhaps the least rock ‘n’ roll spot in all of Washington: a generic, five-story teal condominium in an area of town widely considered Seattle’s least cool neighborhood (it’s a block from a Petco).

Perhaps you are wondering how I knew where all these people perished; the truth is that I did not. The guided Seattle death tour was provided by Hannah Levin, a rock writer for the alternative newspaper The Stranger and a freewheeling expert on local tragedies. Of course, all the aforementioned demises pale beside the Citizen Kane of modern-rock deaths: the mighty K.C. This is what Levin and I discuss as we maneuver the long and winding Lake Washington Boulevard, before finally arriving in what used to be Kurt Cobain’s backyard.

“In the weeks before he killed himself, there was this litany of rumors about local singers dying,” Levin says. Back in ’94, she worked at Planned Parenthood but was immersed in the grunge culture. “There was a rumor that Chris Cornell had died, and then there was a rumor that Eddie Vedder had died. So even though a bunch of my friends called me at work and said Kurt was dead, I didn’t believe them. That kind of shit happened constantly. But then I went out to my car at lunch to smoke cigarettes and listen to the radio. My radio was on 107.7 The End, which was Seattle’s conventional modern-rock station. And as soon as I turned the ignition key back, I heard the song ‘Something in the Way.’ That’s when I knew it was true, because The End would have never fucking played that song otherwise. It wasn’t even a single.”

The greenhouse where Cobain swallowed a shotgun blast was torn down in 1996; now it’s just a garden. One especially tall sunflower appears to signify where the Nirvana frontman died, but that might be coincidence. When we arrive at the site, there are four guys staring solemnly at the sunflower. One of them is a goateed 24-year-old musician named Brant Colella. He’s wearing a Glassjaw sweatshirt, and it has been a long time since I’ve met someone this earnest. Colella makes Chris Carrabba seem like Jack Black.

“I’m from New York, but I moved to Portland to make music. I’m a solo artist. I used to be in a band, but my band didn’t have it in them to go all the way, and that’s where I’m going,” he says, and then looks longingly toward the sunflower. “His heart is here. My heart is here, too. I wanted to see where Kurt lived and hung out. I wanted to see where he was normal. The night before he died, I had a dream where Kurt came to me and told me that he was passing the torch on to me. Then we played some music together.”

Colella was 15 when Cobain died on April 5, 1994. Last night, he and his friends attended a Mariners game — Ichiro Suzuki hit a grand slam to beat the BoSox — but Colella wants to make it very clear that seeing Cobain’s house was his primary motivation for visiting Seattle. He also wants to make it very clear that (a) he hates people who wear Abercrombie & Fitch and (b) that Kurt probably didn’t kill himself.

“There are some people who assume he was completely suicide-driven, but he wasn’t like that,” Colella says. “I don’t want to stir up waves and get killed myself, but the information that indicates Kurt was murdered actually makes way more sense than the concept of him committing suicide. But I’m not here to point fingers and say Courtney Love did it. Only God knows the answer to this question. And I realize there are people who want to believe Kurt Cobain committed suicide. People are kind of broken into two factions: There are right-wingers who want to use his death to point out that this is what happens when you listen to rock ‘n’ roll, and there are also all his crazy fans who want to glorify depression and have Kurt be their icon forever.”

When Colella first said this to me, I thought it was reductionist, simplistic, immature, and — quite frankly — pretty stupid. But the more I think it over, the more I suspect he’s completely right. Except for the murder part.

Aberdeen, Washington (Monday, August 18, noon): Kurt Cobain’s hometown can be described with one syllable — bleak. Everything appears belted by sea air. The buildings look like they’re suffering from hangovers. Just being here makes me feel tired.

In the early 1990s, the suicide rate in Aberdeen was roughly twice as high as the national average. This does not surprise me. It’s also a hard-drinking town, and that doesn’t surprise me, either: There are actually road signs informing drivers that the Washington DUI limit is .08 (although it would seem that seeing said signs while you are actually driving your vehicle is like closing the barn door after the cows are already in the corn).

I notice these roadside markers as I drive around looking for a bridge that does not exist.

What I am looking for is the bridge on the Wishkah River that Kurt Cobain never lived under. He liked to claim that he did. Nevermind’s “Something in the Way” is the supposed story of this non-experience. It’s quite possible Cobain did hang out down there, since hanging out under bridges is something lots of bored, stoned high school kids are wont to do. But Cobain didn’t really live under any bridge; he just said he did to be cool, which is a totally acceptable thing to do, considering what he did for a living. Being cool was pretty much his whole job.

There are a lot of bridges in Aberdeen — this would be a wonderful community for trolls. I walk under several of them, and I come to a striking conclusion: They all pretty much look the same, at least when you’re beneath them. And it doesn’t matter if Kurt Cobain slept under any of them; what matters is that people believe he did, and that is something they want to believe. Maybe it’s something they need to believe, just like they need to believe that a legend’s death means something. If they don’t, they will be struck with the depressing revelation that dead rock stars are simply dead. Cobain’s death was no more remarkable than anyone else’s — it was just more “newsworthy,” which is something else entirely. All he did was live, sing, and die. Everything else is human construction. Everything else has nothing to do with the individual who died and everything to do with the people who are left behind (and who may even wish those roles were some how reversed).

As I walk back to my car and prepare to return to the world of the living, I think back to the conversation I had with the unabashedly annoyed man who runs the Hotel Chelsea. It turns out that he was right all along: I am not a serious person. I do not have any understanding of death. And I am looking for nothing.