Art Alexakis is nursing a broken foot. Sustained “trying to dodge somebody in a doorway — I didn’t want to trip over them and I tripped and fell,” the Everclear frontman has no intention of missing his annual Summerland Tour, which this year features ’90s and ’00s alt-radio contemporaries like Fuel, Toadies, and American Hi-Fi. “For my age I heal ridiculously well,” he says over the phone. “It’s good and it’s bad. I get it from my dad: My dad’s 93 years old, and he’s way outlived his usefulness, big time. That’s just too old. Who wants to be that old?”

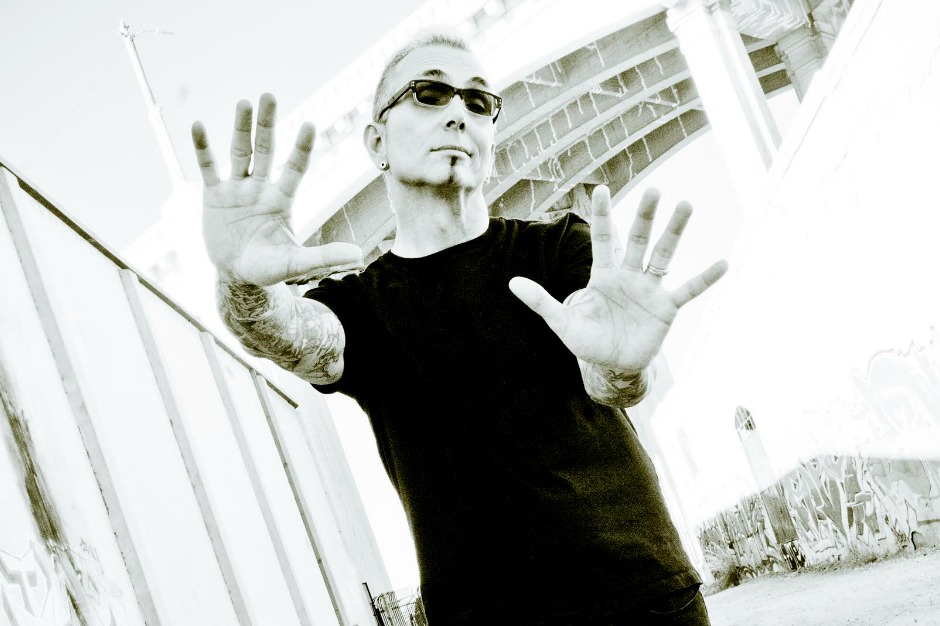

Alexakis, who recently released Everclear’s ninth studio album, Black Is the New Black, last April, sounds dismissive when he mentions his dad — a shadowy, mostly absent figure who left when his youngest son was only five years old. Though the 53-year-old wouldn’t really begin to lyrically explore feelings of paternal abandonment until 1997’s So Much For the Afterglow hit single “Father of Mine,” the still bleached-blonde frontman poured myriad other childhood sufferings into his band’s career-boosting sophomore release, Sparkle and Fade, which turned 20 this past May.

Weaving autobiographical tidbits from his own life into fictional tales of drug abuse (“Chemical Smile”), suicide (“Heroin Girl”), and interracial dating (“Heartspark Dollarsign”), Sparkle and Fade is clearly steeped in the pain of seeing too much too early in life: The singer lost his older brother to a heroin overdose when he was 12. In the same year, Alexakis, who had his own substance struggles, witnessed his girlfriend’s suicide via the same narcotic.

As much dysfunction spills out of his 1995 record, Alexakis was — and still is — capable of instilling a sense of optimism in the mess. “I think a lot of my music’s like that, even our new record is really dark, but I think there’s a lot of hope there. Sometimes you’ve got to squint a little bit to find it.” SPIN called him up to re-examine the record that broke his career, the anxiety and depression that followed, and what parts of Sparkle and Fade are culled from his own life.

Sorry about your foot. You going to be okay for the Summerland tour?

Are you kidding me? Get out of here; of course. It’s going to be fine. It feels better a day into it already. They’re just going to put a pressure boot on it and I’ll put ice on it at night.

It’s one of those things that we all deal with. We all deal with the not-pretty aspects of life fine. Just don’t talk about it. It’s funny — my mom, when she started getting older, she became that person [who broadcasts their ailments]. I didn’t think she thought she was going to become that person, but boy, she did. God bless her, but I guess your focus becomes these smaller things in life. If you have that every day, it’s a good day. Can I ask how old you are?

I’m 28.

Oh my God. I have a 22-year-old daughter. I don’t want to hear “engagement” until she’s at least 30. It’s just like, have fun. Learn, live, do all those stupid things you’re not going to do in your 30s and 40s, because once you have kids you’re not doing it. You’re not jumping off bridges and bungee-ing. You’re not backpacking through Transylvania. And I think when people get married, they should not have kids for five or six years. Just enjoy having a partner, doing cool things together.

That’s pretty much where I’m at right now.

Well, there you go. Spoken by the guy that’s been married four times. You know, SPIN put us on the cover for this record.

Yeah, I remember it.

How? You were like, 12.

I’ve seen it in the years since.

Okay, I have one bone to pick with SPIN. They sent out the cover to us — what it was going to be — and it was this really cool picture of us after we did the photoshoot and everything. This really cool picture. And so we sent it back saying, “Awesome.” And then they put that picture on the cover of us looking like total goofballs, which now I can appreciate, but at the time I was too punk rock. It just wasn’t punk rock enough for me. But, you know, I grew up after 20-some years.

I can’t speak for what the art department was like then, but —

I’m just teasing, I don’t care. I mean, we were on the cover of a major magazine; I cared, but really I’m just joking. Even at the time, I was like, “Oh, I’m on the cover of SPIN. Let’s just enjoy that.”

Speaking of photos, when Sparkle and Fade came out, what led to the cover art being pictures of you guys as kids?

Basically, my idea was just to show us when we’re young and perfect, and before all the damage sets in and the baggage really starts weighing you down and all that stuff. And then the flip side of it was to show the end: Craig [Montoya, former Everclear bass player] and me were great. Finding those pictures was no problem. That was the picture of me — I had just shot up a bunch of coke — the picture of me on the back with the long hair and I’m in the army jacket. I had just shot up a whole bunch of coke, and I was going on a motorcycle ride through the ghetto where I lived.

And that picture of Craig, he had been on a bender. Finding a big picture of Greg, our drummer at the time, was really hard, because he never really rebelled. He was just a happy middle-class kid. Went to college, loves his parents, you know, the idyllic life, which is awesome. But that wasn’t mine and Craig’s experiences at the time. And so I put a picture of him with the dreadlocks, which I thought was bad because again, I thought I was very punk rock, and that whole hippie thing was just a dark stain on your soul as far as I was concerned at the time. But it was really funny because young girls always thought, “You look great with dreadlocks!”

What prompted you to single out these lyrics for an album title?

To be honest with you, I hate to use the word because it’s kind of cheesy, but it was just a very organic thing. I didn’t name the record, I always feel like records name themselves, and you’ll figure it out. The next record we did — just case in point — I went into it thinking it was going to be called “Pure White Evil,” but the album changed. I made the record, I wasn’t happy with it; I pulled some songs off it, wrote some more songs, went through the old songs; and then at the end of it, during that process, wrote a song called “So Much for the Afterglow,” and I’m like, boy, that’s a “F—k you” to all the people who’ve given me s—t about this album, that we’re going to fail and our sophomore slump. And then I put a song on there called “One Hit Wonder,” just to f—k with people, basically.

Sparkle and Fade, that seemed that that’s what it was dealing with: It was dealing with a lot of stories about people going through tough times and trying to find their way out of it, trying to find the light at the end of the tunnel.

There are a lot of pop-punk riffs on the record (“My Chemical Smile,” “Her Brand New Skin”). Were you in any sense paying homage to the stuff you were listening to at the time?

Probably. You’ve got to remember, I’m 53. I was playing in bands when I was 14, 15 years old, and so the whole power-pop or pop-punk thing — I don’t want to say I was part of creating it, but it was going around when I was coming up and kind of making my bones back in the day. All the bands that helped start that, from Bad Religion on up to the Descendents, which would probably be the prototypical pop-punk band of all time — I mean, when I first heard that in ‘85, on college radio, their song “Cheer,” I was just like, “Yeah, that’s where I’m going.” I loved the Beatles and I loved punk rock, and I loved big guitars, and that’s where I wanted to go.

I’ve always been a softie for all sorts of kinds of music, like singer-songwriters. Everclear was a combination of hard rock plus punk bands meets singer-songwriter, because that’s kind of me.

I was reading an interview you did last year, and the interviewer trips up because they think “Heroin Girl” is your story. You said, “No, it did not happen to me. It’s not autobiographical. I’ve said this 1,000 times in the press.”

And I do! You could go back and look at the huge, phonebook-sized press that was done over a period of 20-some years. I’ve always said that, even back then. Just for an example: After Sparkle and Fade came out, people started coming out of the woodwork, and I got confronted in a parking lot outside a show, and this girl’s just like, “You know what, I’m just here to tell you that we’re friends with Esther’s family, and they’re really upset about it and are probably going to press charges.” And I go, “Whose family? Esther’s? You mean from the bible?” They’re like, “No, Esther from ‘Heroin Girl,’” and I go, “She’s a made-up character.” I go, “Either you’ve been misled, or you’re full of s—t. One or the other. So don’t threaten me, how about that?”

I get that stuff all the time. I don’t get the negative crazies so much any more. I’m sure they’re there, but I don’t get them that much any more. Mostly, I think it’s because it’s after the fact. When you’re on the rocket ride up and everybody’s scrutinizing everything, I think that that’s a different perspective than it is now.

So how much personal experience, if any, lies within “Heroin Girl”?

My brother died of a heroin overdose. I had a girlfriend that killed herself by injecting heroin, so she died of heroin overdose, but it was a suicide. She wasn’t named “Esther.” “Found her out in the fields” — I made that up.

But the line specifically where the police said it was just another overdose — when my brother died of a drug overdose, it was a Saturday. Sorry, I’m a little emotional even now. They called my mom at work to say, “Hey, you need to come down and identify this body, we think it’s your son.” Are you f—king kidding me? They called a woman at work to tell her that her son was dead. I was little — I was 12; I was playing at baseball, little league. And my sisters drove over to find my mom just walking through the parking lot, out of her mind. When they went down to the police station to identify my brother, there were a couple of cops over in the corner talking, and they were like, “Nah, it’s just another overdose, stupid kid.” And my mom walks over to them and goes, “Not another overdose. That’s my baby. That’s my son.” So part of this is from my life, but some of it isn’t.

What I hear on Sparkle and Fade is a lot of reoccurring themes of fantasy and escape.

Absolutely. I made a comfort zone. The song “Summerland” — I’d been that character of like, “Let’s get f—king drunk and make it all go away for a day. Let’s get in the car and drive.” I grew up in Southern California, where, when you’re younger, no one has apartments, but you have cars. So you party in your cars and you just drive. We’ve got money for gas and we’ve got money for booze, let’s go. Which is a horrible idea! But when you’re 17, 18, 19, 20, that’s your little world. You don’t have it at home, you don’t have it anywhere else. I come from car culture, which is a whole different way of thinking from people who grew up in places with rapid transit.

I guess Sparkle and Fade was kind of my escape route. It’s funny, I wrote the song “Santa Monica” — most bands from that era that had really big hit songs that just really kind of defined the band at the time, and it’s fair to say that about “Santa Monica”: “They had that song when they got signed, that’s what they got signed for.” We didn’t have that song. We got signed to Capitol, and I started writing songs, in our rented house — we rented an nicer house when we got some money — and I had a 2-year-old at home and my second wife, and every night after the baby would go to bed, I would write songs out on the front porch so I wouldn’t wake anybody up. The next day, the band would come over and we’d go down in the basement, and we’d work out songs that I’d written the night before.

I suffered from anxiety and depression really bad then, especially after getting signed — it was intense, it was weird. I’d come up through a housing project and was a child of abuse and abandonment and all this stuff, and I wasn’t used to people liking me and saying good things about my band or about what I do. When that happened, that became a different kind of anxiety. I couldn’t really process it or understand it at the time. Looking back, I think I’ve got a better grasp on it.

Was it an “all this could fall apart any minute” kind of anxiety? Or “how do I live up to the expectations people have set for me?”

You’re smarter than I am. You’re going deeper than I think I did at the time. It was just pretty much, “What the f—k is this?” I’m used to people saying no; I’m great with that. I’m great with saying “F—k you” to the world. But when people are faking nice — because it was fake.

Let’s talk about “Heartspark Dollarsign.” I haven’t heard much of a discussion of race in alt-rock. How much of this song is based in real experience, and at the time, were you interested in talking about race relations?

I’ve always wanted to talk about racial things. “Heartspark Dollarsign” was written in my previous band, called Colorfinger, which originally I wanted to call “Colorblind.” So there’s always been that aspect of — you know, I grew up in a black neighborhood, so the things that concerned a lot of people didn’t concern me. I’d always been a pretty sexually charged kid, and I had girlfriends at a very early age. If you look at all the women I’ve ever dated, there’s no type. I don’t have a type. I think beauty and intelligence and humor, those are devoid of type. I liked every type of gal, back when I was dating.

My mom, you have to give her credit. She’s from the Deep South, from the Depression; she wasn’t overtly racist, she didn’t use the n-word, she would smack us if anyone even hinted at something like that. To be compassionate to her, it’s really hard to shake what you learn when you’re a kid for some people. Not for everybody, but for some people. And me dating black girls and Asian girls and Hispanic girls, Filipino girls was hard on her. I think the hardest one for her, which is sad to say, was the Jewish girl. She wasn’t “rich rich,” but for as poor as we were, she was pretty well-off. It might have been more the money thing than it was the Jewish thing.

But anyway, I dated a [black] girl, and it was this three-week whirlwind — like, from the time we looked at each other across the room, it was on, you know? It was just on. And she came out to meet my mom, and my mom was horrible to her. And the next day we went and met her parents. Her mom was half-black, half-white and her dad was black, and he was nicer to me than her mom. Her mom was just flat out like, “You shouldn’t be here.” She just didn’t want any part of that world, and it affected our relationship. We were young enough that we weren’t in a place where we could go tell the world to go f—k itself. We said we were, but we really weren’t. Not at that point. And that’s what that song’s about, is just embracing the value of love and passion — your heart.

What is “My Sexual Life” about?

It’s in some ways about my sexual life. The characters in this song — a lot of it came from myself, a lot of it came from partners I’ve been with and just things I’d seen and lived through and been close to. And I just take it all together and make characters out of it a lot of times. And that was at a time when it was hard for a woman to say, “Yeah, you know, I want what you have. You come, I come.” That wasn’t an accepted thing then. It was in some small circles of super-educated people, but the world for the most part — and it still is, if you start getting under the darker areas of our country and our world. Most sex for women is like rape. It’s not a beautiful thing that writers write about.

Do you have a sentimental favorite from of Sparkle and Fade?

What’s funny is, we just did the 20th Anniversary tour in Australia and New Zealand, and we played the whole album. We play the first eight songs pretty much all the time. But the second half of the record, from “Her Brand New Skin” on, we just started playing and working on them. We played every night for a couple of weeks. And to be honest with you, I don’t think there’s any songs on there that I didn’t enjoy playing or found weird.

One song I really enjoyed playing was “Pale Green Stars.” That’s pretty autobiographical. There was a version, I don’t know if it’s still around, but originally, it said, “Anna is in love with the side of the moon.” It was “Anna,” not “Amanda” — that’s my daughter. I changed it to “Amanda” because her mom thought it was just too intensely personal. I’ve had people go, “I know Amanda, and she’s doing really well, I just wanted you to know.” And I go, “Who?” And I feel really bad. I’ve met girls named Amanda who have pale green stars tattooed on their skin, and there was one time when I’d tell them the whole story and say, “No, you shouldn’t do it,” but now I don’t even argue. I just go, “Awesome.” See? I’m becoming a dad. I’m on my way to being a grandpa.