This story originally appeared in SPIN’s July 1994 issue.

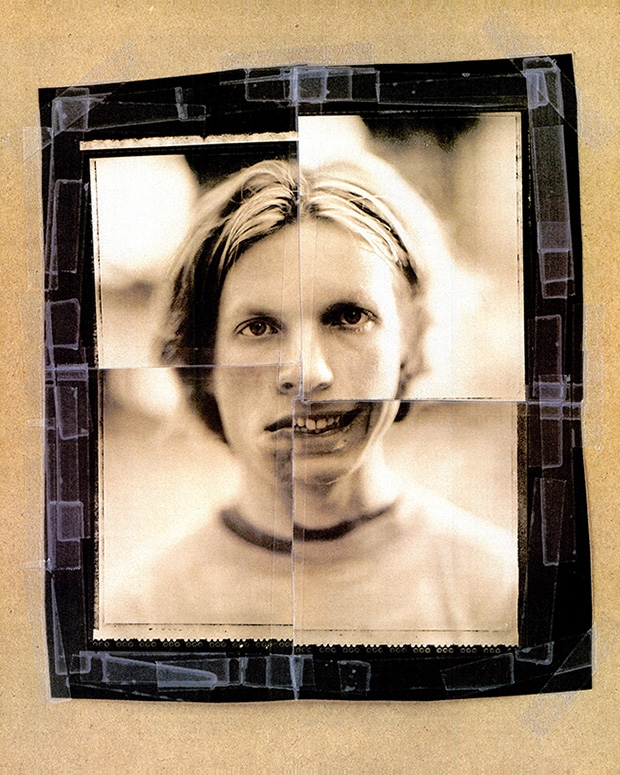

This is Beck. He’s not a slacker, an angst-ridden mouthpiece, or a loser, baby. He’s a cosmic naïf with one foot on the zeitgeist wahwah pedal and a scary inner-bluesman aching to turn it loose.

“The best place to view Los Angeles of the next millennium,” wrote social historian Mike Davis in the prologue to his 1990 dissection of L.A. development, City of Quartz, “is from the ruins of its alternative future.” Granted, the specific ruins Davis was discussing were the crumbled vestiges of the former utopian socialist hamlet of Llano del Rio, its vacant desert acreage awaiting annexation as a subdivision for the white flight of the 21st century; and, of course, his definition of alternative had nothing at all to do with a contrived corporate radio format.

But, oh well, whatever, never mind. I figured that the best place to view Los Angeles’s “alternative” future was from the ruins of its indie-rock past, from the hieroglyphic squiggles of its bands’ promotional graffiti, from the faded small print on its wrinkled-up paycheck stubs.

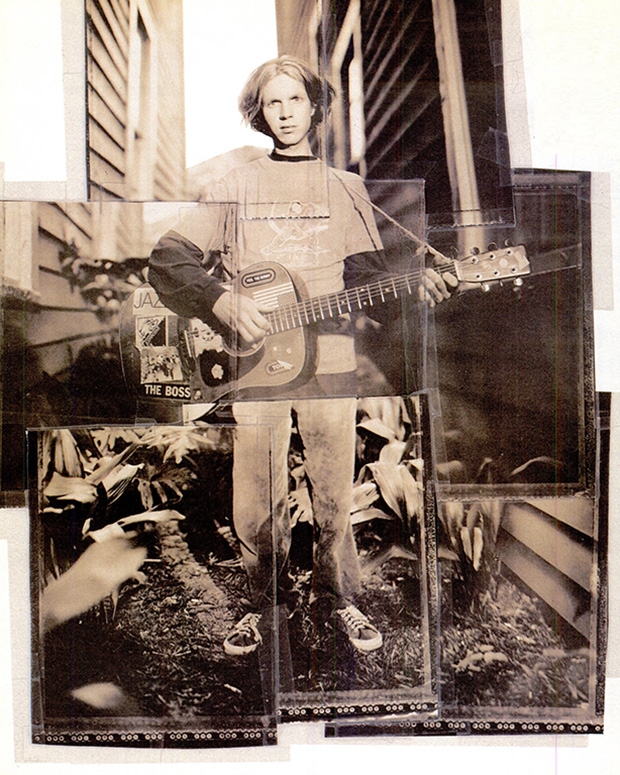

And so that future, as embodied at the moment in the scrawny frame of Beck, a.k.a. Beck Hansen, a.k.a. Beck Campbell, 23-year-old folk-rap-noise balladeer and MTV Buzz Bin sensation, is busy excavating the rubble of his own past for me.

“See that sign over there?” asks Beck, pointing out the car window as we drive down Hyperion Avenue in the fading light of day. “I painted that sign.”

I crane my neck to see a plain brick building, its facade festooned with big block letters — THRIFT STORE. The nondescript storefront testifies to how far the sandy-haired urchin has come in a very short time. Only two years ago he was painting electric pink and blue signs on lingerie stories, eating Cheetos, and making living-room cassettes of his twisted pseudo-folk songs for friends.

Today, he still eats Cheetos and makes living-room cassettes, only now his single, “Loser” — recorded in just a casual couch-potato scene — has been the hottest request on the radio stations across the country. An irresistible snatch of honky hip-hop, it’s a demi-dadaist rap in the (somewhat clunky) cadence of Bob Dylan‘s “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” laid over a funky backbeat and grafted to the most infectious slide-guitar lick since the Allman Brothers‘ “Midnight Rider” was drafted into a beer commercial. His debut album, Mellow Gold, originally slated to be released on L.A. mini-indie Bongload Records, has instead come out on mammoth DGC.

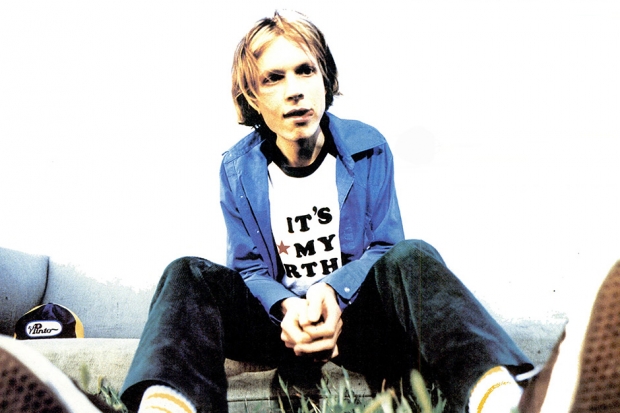

The critical avatars of the boomer media have anointed him a spokesman for his generation, an honorific with slightly less power than the Prince of Wales — call it the Prince of Wails — and ten times the royal pain in the ass. Such a burden sits uncomfortably on Beck’s head and shoulders, which are currently covered by a blue polyester shirt and a leather-brimmed baseball cap with the Ford Pinto logo on the front. (The Beastie Boys‘ Mike D, an acquaintance of Beck’s and no ’70s sartorial slouch himself, says Beck is “one of the best dressers I’ve hung out with in a while,” citing in specific his corduroy flares, Jordache jeans with the hems let out, and “a thrift-store T-shirt collection that can rival anyone’s.”)

The Dylan comparisons are dangerous enough and this spokesperson stuff just doesn’t wash with him. “Jesus!” exclaims Beck at the very notion of being a mouthpiece for millions. “You’d have to be a total idiot to say: ‘I’m the slacker generation guy. This is my generation, we’re gonna fuckin’ — we’re not gonna fuckin’ show up.’ I’d be laughed out of the room in an instant.”

So let’s set one thing straight: Beck is no slacker. “I’ve always tried to get money to eat and pay my rent and shit, and it’s always been real hard for me,” he says, affecting a certain amount of B-boy swagger. “I’ve never had the money or time to slack.”

For the past year, Beck’s been collecting unemployment checks after being laid off from his $4.00-an-hour video-store job, unable to find any work at all. He doesn’t even watch TV; though he’s performed a song called “MTV Makes Me Want to Smoke Crack” for the last few years, he’s never really seen the channel. “I was blissfully ignorant,” he admits.

“If you told me a year ago I was going to have a record deal, I would have laughed at you,” he says. And not just one deal. In addition to Mellow Gold, he has a new album on Flipside, Telepathic Astromanure, as well as an album and a seven-inch single to be released on K Records this summer. With a handful of indie EPs and the full-length cassette Golden Feelings (from Sonic Enemy) out last year, Beck is rapidly becoming as prolific as a low-fi Prince.

The tour continues. Passing a prefab-looking shopping strip, he points out the former location of the video store that laid him off, now itself a figment of the strip mall’s past. On Sunset Boulevard he motions toward Tang’s Donut Shop, an all-night pastry hut where he would hang at 4:00 A.M. getting a “nice sugar rush” while watching homeless guys play high-speed chess.

Further down Sunset, Beck points out a revolving sign for a podiatry office. On one side of the sign is a “before” cartoon foot, propped up on crutches and sporting a miserable frown; on the other is the after-care foot, beaming with post-appointment relief. The sign gets turned off every night. A few years back, Beck lived in a house right behind it. He and his roommates would sit around at dusk, drinking beers and waiting for the sign to stop spinning. If the sign came to a halt and the happy side faced the house, he says, they’d head out for action, but if the sad foot pointed in their direction, they’d call it a night.

He’s had jobs moving refrigerators and furniture. He worked at children’s birthday parties as a hot dog man, serving root beer and hot dogs to little kids. As his song “Beercan” attests, he quit his job blowing leaves, but not before his leaf-blower ended up on stage with him as a musical instrument.

“It’s a very large population here,” he says of leaf-blowers. “There’s a leaf-blower contingent. There’s no union that I know of so far, but there’s certainly a spiritual brotherhood. They are the originators of noise music. It’s like a cross between a Kramer guitar and a jet pack.”

Later, he tells me, “All the shit that’s happening to me now is totally insane, because if you ask anybody that knows me, they’d tell you I’ve had the worst fucking luck. This is all an avalanche of confetti and balloons and kazoos. Before, the party was just an empty room with a bare light bulb on the ceiling. It was pretty bleak.”

When I suggest that with such sentiments he’s veering dangerously toward Vedderian angst, he laughs and begins sarcastically whining in a pinched voice, as if lecturing his inner Jeremy. “Oh, the tragedy and the anguish. You just gotta Rage Against the Appliance, man. The toast is burning and you just gotta rip it out and free it before it fills the house with smoke. Rage Against the Toaster.”

If not for “Loser,” Beck would still be a street-fighting folk singer with a distortion pedal and a dream, if not quite a — well, loser. Beck’s path through the pop charts is certainly one of the most unlikely sagas in recent music history, a harmonic convergence of indie-rock dissonance and the new A&R paradigm.

Gigging at L.A. coffeehouses and clubs and circulating his tapes, Beck was spotted by Bongload co-owner Tom Rothrock, who eventually put the cosmic naïf in touch with producer Karl Stephenson. Goofing around with some songs over at Stephenson’s house, Beck laid down some slide guitar which Stephenson recorded, looped, and set to a hip-hop beat. Beck wrote some lyrics on the spot and got on the mike trying to deliver a Chuck D-style rap. “When they played it back, I was like, ‘I’m the worst rapper!’ So when I did the chorus I was just putting myself down.” Meaning the put-down currently being appropriated for an already put-upon generation — “I’m a loser, baby, so why don’t you kill me?” — is actually just Beck’s critique of his own Chuck D imitation.

While Beck’s collision of folk and rap might seem jarring, to Mike D it’s not an incongruous mix at all. “He fits into the nomadic folk tradition of Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, the whole traditional coffeehouse balladeer tip,” he says. “But his hip-hop side legitimizes Public Enemy as the real folk music of the ’80s, because he draws on that aspect just as much as on anything else that he’s picked up along the way.”

“Loser” sat around for over a year, until Bongload released it in March ’93 in a pressing of 500 copies, just for friends and local college radio stations to play. “But last fall these really heavy-duty commercial stations starting playing it,” says Beck. “They didn’t even have copies. They were making cassette copies off of someone who had a copy of the vinyl.”

Unwittingly, his song played into the hands of those who would demonize his peers as do-nothings. “I didn’t even connect it at all to that kind of message until they were playing it on the radio and I heard it, and they said ‘This is the slacker anthem,’ and immediately it just clicked and I thought, ‘Oh shit, that sucks.’ ”

Beck hasn’t sung the line live in over a year. “It was a fun song to make, and when they take it out of context like that, it’s kind of a drag. It’s tongue-in-cheek, you know. It’s not some anguished, transcendental ‘cry of a generation.’ It’s just like sitting in someone’s living room eating pizza and Doritos.”

The self-deprecating stance of “Loser” is nothing new. The song mines the rich tradition of self-mocking shemphood that probably made its first dent on the hit parade with the Beatles‘ 1964 “I’m a Loser,” continuing on through the Stooges‘ “I Wanna Be Your Dog,” and Sebadoh‘s “Losercore.” Sub Pop even put “LOSER” in big block letters on its T-shirts back in 1988. Like rappers’ use of the N-word and gay activists’ use of “queer,” embracing “loser” may even have an empowering quality, although it may just as likely indicate that young people have internalized their buzz-word abuse at the hands of boomers.

Now that he’s helped perpetuate this generational “Loser” phenomenon, Beck has come up with an alternate plan to combat it. “I’m going to get this gigantic 40-foot-wide pair of pants and get all the kids to get in the pants with me, and we’re going to do aerobics. The problem with these kids is they’ve just gotta get in shape. I’m just going to be sort of the exercise instructor…”

“Of a generation,” adds Chris Ballew, Beck’s backup guitarist.

“A human aerobics tape, if you will,” continues Beck. I suggest that perhaps Neil Young has already explored this oversize theme as a tour motif. No problem, says Beck. “You have to pay homage to your elders. That’s part of the new respect with this generation. Once they’re more in shape they can pump their fists with confident biceps and all that shit.”

Beck’s unconventional upbringing prepared him for his sudden explosion into the national zeitgeist. His mother, Bibbe Hansen, was a former scenester at Andy Warhol’s Factory, appearing in Warhol’s (unreleased) film Prison along with Edie Sedgwick. The daughter of Al Hansen, an artist who was part of the Flexus movement in the 1960s with Joseph Beuys, she raised Beck and his brother with a deliberately hands-off approach, stressing self-reliance. She takes no credit for the way he turned out. “Oh no, he’s an original,” she says when asked if her bohemian background had somehow influenced him. “He did it all completely on his own. I wouldn’t have a clue as to how Beck became Beck.”

As a kid, while his single mom was struggling to make ends meet (and his father, whose surname is Campbell, was off starting another family), Beck was shuffled back and forth between L.A. and Kansas, where he lived with his paternal grandfather, a Presbyterian minister.

At age 12, he returned to live with his mom in L.A. where the hardcore scene was in full flower. “She would let punks stay at our house who didn’t have a place to stay,” says Beck. “She actually claims that Darby Crash crashed out a few times on our living room sofa. She was older, but she kind of felt sorry for them.” Beck’s mom confirms that her acts of charity reached out to members of the Screamers, the Controllers, and yes, Bobby Pyn, later known by his Germs stage name Darby Crash. “Punk was like the best thing I’d heard in years,” she admits. “So yeah, there was always a peanut butter-and-jam sandwich and a couch.”

One day over at a friend’s house, Beck found a copy of a Mississippi John Hurt record from the ’60s. “It was shrink-wrapped, it hadn’t even been opened, and it was this insane close-up of his face, sweating, this old, wrinkled face, and I took it,” he says with more than a trace of Midwestern twang. “I was going to return it, but I didn’t. I loved the droning sound, the open tunings, the spare, beat-down tone. And his voice was so full. He just went through so much shit, and it comes across really, really amazing.”

Exhilarated by his discovery, he began banging out tunes on an acoustic guitar that was lying around the house. Around this time, after finishing junior high, he dropped out of school. “I didn’t have any friends, it felt kind of like a waste to me.” Instead of high school, he’d sit around his room all day playing along with his Charley Patton and Blind Willie Johnson records.

To get over his shyness about performing, he would go to the park near his home in L.A.’s Little El Salvador neighborhood and serenade the Spanish-speaking soccer players. “There would be these Salvadorian guys playing soccer and this little white boy playing Leadbelly songs. Nobody would listen,” he says. “It was really pathetic.”

Some days he’d board the back of a bus, riding the Vermont line down through South Central and back around up to Hollywood, practicing Fred McDowell slide-guitar licks, changing the setting of the lyrics from the rural south to his mass transit surroundings. Every now and then another musician would come to the back and jam with him, but mostly he got blank stares or verbal abuse.

When he was 16 or 17, Beck began making tapes by recording onto one cassette player, then playing along with that cassette player into another, repeating the procedure until the sound was completely distorted. The screwed-up tape speeds resulted in a helium-enhanced vocal effect of which Beck is still fond. He was also weaned on records by Sonic Youth and atavistic aut-rockers Pussy Galore, whose album he bought out of curiosity at age 15 because he had been “a total James Bond freak” as a little kid. “Pussy Galore was a Bond character so I bought it. It was so distilled and pure. It had all the elements, just turned up.” To Beck, noise became like a drug: “Once you start doing it, you can’t stop.”

In 1989, he set out for New York with a girlfriend, only to have her ditch him soon after arrival. Hanging around the Lower East Side without a place to live, he crashed on friends’ couches and in anarchist squats, working a succession of odd jobs, such as taking ID photos at an Upper East Side YMCA and checking jackets at an East Village bookstore.

One night, sitting out in front of Chameleon, a bar on 6th Street and Avenue A, picking his guitar, a fellow wayward troubadour played him a number he’d just written about potato chips. Blown away by this deep-fried approach, Beck discovered that such bizarre subject matter was being explored regularly inside Chameleon on their open mike nights, and he immediately took to performing there and at ABC No Rio as part of the “antifolk” scene that had already spawned Roger Manning and John S. Hall.

As he worked at honing his songwriting craft, Beck fell under the charismatic spell of poet-performer Mike Tyler, at the time the publisher of American Idealism Rag, or A.I.R. “He knew Bukka White, you know what I mean?” says Tyler of Beck. “He could get up on stage with somebody else and it just always seemed perfect. All the false alternative hypocrisy just seemed to fade away when I saw him.”

Sunlight streams through the window and onto the cluttered record stacks at KXLU out in the Westchester section of L.A. It’s a beautiful southern California afternoon, but we’re jammed into the college radio station’s minuscule offices on the campus of Loyola Marymount University where Beck and Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore are broadcasting a live performance.

Crammed practically onto each other’s laps in the tiny studio, Beck and Moore look like micro- and macro-versions of one another: Moore wearing sunglasses and a plastic visor; Beck, the test tube Moore, in a flannel shirt and his Pinto cap. As the duo serenade a pudgy DJ in a Rollerskate Skinny T-shirt across a table full of recording equipment — Moore assaulting his guitar, Beck gurgling into a mike — the feel is improvisational and the theme is ferocious noise.

“The next song is called — what’s the next song called?” wonders Beck. “The next song is called ‘Super Christ,'” says Moore, announcing what will probably be a big hit among listeners at this Catholic university. Beck launches his Moog into a succession of burbles and squiggles while Ballew, the only member of his band present, plays percussion by scraping the metal arm that supports the studio mike.

Suddenly, mid-song, Beck runs out of the studio, down the hallway, and disappears. Three minutes later he comes running from the opposite end of the hallway back into the studio. A few songs later, he repeats his disappearing act. Later, he tells me he had set his Moog to play a sustaining note while he ran a lap around the station office, rode down the elevator and back, all with the keyboard continuing to bleat away.

After 30 minutes more of joyful noise, Moore calls it a set and the DJ segues from the super-session into Superchunk. A young station staffer ambles up to Beck as he’s unplugging his synthesizer.

“Do you know how to play the piano, or were you just faking it?” she asks.

“I can’t really play anything,” he replies, glancing up wide-eyed. “I just try to feel my way around it.” He pauses, looking perplexed. “Why, did it seem like I was unknowledgeable?”

The girl, perhaps sensing a confrontation between the forces of market-driven conventionality and the free-form impulses of the avant-garde, evades answering the question. Beck packs his Moog into a beat-up old suitcase worthy of a door-to-door salesman and disappears out the studio door. Five minutes elapse. Then Ten. Moore, responsible for driving Beck to another radio appearance, begins searching.

“Maybe he’s lost,” offers the girl.

“He is lost,” answers Moore, speaking generally. “And sometimes he gets found. These days, he gets found a lot. It’s like Hendrix, he took drugs to get straight.”

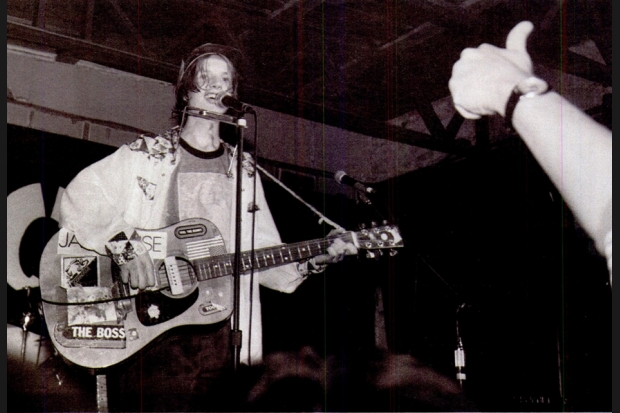

It’s Friday night, and downtown L.A.’s Troy Café is abuzz with more than just caffeine. A tiny coffeehouse whose narrow confines make CBGB look like Madison Square Garden, the Troy is vacuum-packed for the second public performance by Beck’s band, the crowd stretching from the cappuccino machine out on to the street, despite the gig’s lack of advertising.

“This is a total harmonica freakout from 1896 called ‘One Foot in the Grave,'” announces Beck as he takes the stage alone, launching into a frenzied mouth-organ blues. Stomping his foot on the floor for percussion, bellowing vocals through a fuzzed-out monitor, he sounds like an ancient southern bluesman trapped in a teenage smartass’s body. It’s roots music that’s been peroxided blood.

After the solo number, the rest of the band comes up on stage: guitarist Ballew, whom Beck met in Seattle when Ballew jumped on stage at a solo show to provide human beatbox sounds for “Loser”; bassist Dave Gomez, a burly veteran of several local hardcore bands whom Beck describes to me later as “a Long Beach O.G.”; and Joey Waronker, a drummer from a musical family (sister Anna plays guitar in That Dog, father Lenny is the president of Warner Bros. Records). For the time being, the group has decided to call itself “After School Special,” although no one is quite sure if ABC-TV will appreciate this.

“This is a crazy little Gary Numan song called ‘New Wave Cocksuckers,'” declares Beck, as he and the band break into an indecipherable, high-speed thrash. “What’s with these ‘LOSER’ T-shirts?” he asks between songs, spotting a familiar message on some chests in the crowd. “Don’t you people have any self-respect?”

A song called “Teenage Wastebucket” begins in a mellow lope, accelerates into a breakneck romp, then suddenly segues back into the slow groove before devolving into a Sonic Youth-style espresso-to-your-skull feedback drone. After Beck flails about like a spastic dervish, nearly trashing Waronker’s drum kit, a female voice calls out, “I love you, Beck!” Picking himself up from the floor with an embarrassed grin, Beck replies, “Thanks, mom.”

Of course, the heckler probably is Beck’s mom: Not only is she the co-owner of the Troy Café, she’s also the guitar player for the evening’s headlining band, Black Fag, a punk-rock performance-art group fronted by a six-foot seven-inch African-American drag queen named Vaginal Creme Davis.

The next night is the band’s final send-off before the tour, and they’ve chosen to celebrate the event at Fuzzland, a roving club that changes locations from show to show. Tonight’s gig takes place in a dilapidated former bowling alley, with the stage set up at the end of one of the lanes. It’s supposed to be a record-release party for Beck’s Flipside CD, but in typical indie-rock form, the records aren’t ready yet.

The show moves through various acts of Beckian theater, including auditioning drummers to fill in for an ailing Waronker (who, as Beck tells it, ate “some fucked-up Satan sushi”), before Beck finally relents and gives the people what they want. “This song is called ‘K-Rock Set My Dick on Fire,’ ” he bellows, introducing “Loser.” In time to the beat, Beck tugs at a chain dangling above him, turning a neon Miller Genuine Draft sign over the stage on and off.

Tonight the Spanish lyric, “Soy un perdidor” (a rough translation of “I’m a loser”) sounds like “signed to Polydor,” and the chorus’s response is “Why don’t you kill yourself?” Raw and distorted, Beck’s rapping more off-kilter than ever, the song bears little resemblance to the smash hit that’s beginning to hang like a dookie rope albatross around his neck. It’s somehow fitting that the show comes to a close with Gomez leaping off the stage and squashing several members of the audience sitting on the floor.

“We need about two or more weeks of rehearsal,” Ballew tells me after the show. How soon till the band leaves on tour? “Two days.” He laughs. “Well, we’ll work it out on the road.”

As I leave the club, I’m not so sure. I think back to Beck’s words in “Pay No Mind”: “Give the finger / To the rock’n’roll singer / As he’s dancing upon your paycheck.” In his live performances, Beck has changed the target from a rocker to a “folk singer.” He might be singing about himself, knowing, as he seems to, the ebb and flow of rock’s fickle spin cycle. He’s a protest singer for the irony age, chronicling the punchline, not the breadline. So he knows full well that someday, probably sooner than later, he’ll be the recipient of that bird.

Oh well, whatever, never mind.