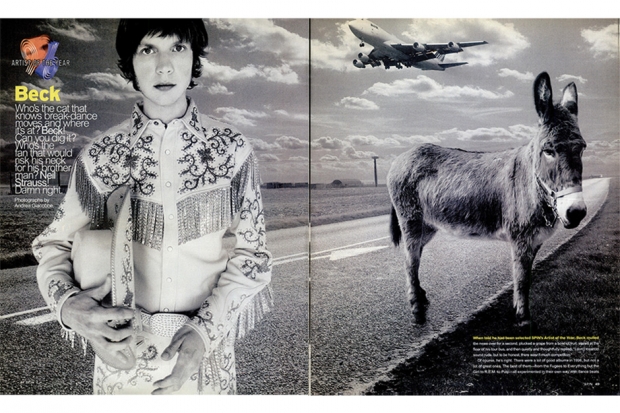

When told he had been selected SPIN’s Artist of the Year, Beck mulled the news over for a second, plucked a grape from a bowl of fruit, stared at the floor of his tour bus, and then quietly and thoughtfully replied, “I don’t mean to sound rude, but to be honest, there wasn’t much competition.”

Of course, he’s right. There were a lot of good albums in 1996, but not a lot of great ones. The best of them–from the Fugees to Everything but the Girl to R.E.M. to Pulp–all experimented in their own way with dance beats and grooves. Even big, bad heavy-metalers like Metallica and White Zombie pledged allegiance to the remix. But when Beck’s Odelay arrived in June, it stood apart immediately–not because it was a perfect album but because it was perfectly imperfect. Its grooves were built from the sounds of braying donkeys and distorted drum machines, all layered so thickly with surplus sound effects and instruments that they became elusive, hard to grasp but easy to dance to. Though vintage keyboards, kiddie toys, a Frogs sample, and answering-machine tapes are all used, the grooves on Odelay are not about collage but about variety, moving from Terminator X noise to Grateful Dead jams. Even the catchiest song on the album, “High 5 (Rock the Catskills),” was sabotaged by seven seconds of Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony.”

Traveling with the 26-year-old Beck and his band on their luxurious, bona fide rock-star tour bus offered a rare glimpse into the contrast between Beck’s creativity and his personality. As we bounced from city to city in Texas, fans approached him not with adulation but with eccentricity, offering him roses picked near a chemical dump, or speaking to him in purposefully fractured English.

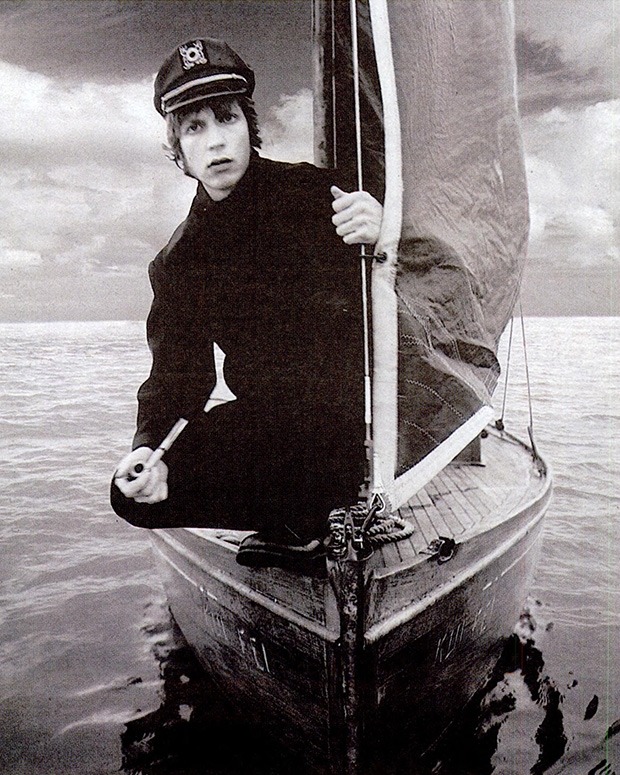

The truth, though, is that Beck– the son of a bluegrass musician and a former Warhol Factory denizen–is more straightfoward and down-to-earth than anyone might expect. Outfitted for most of the trip in a two-sizes-too-big open-collared shirt and a blue blazer, he gives off the impression of being slightly out of sync with the world. But when he wasn’t just plain exhausted from months of touring, Beck was more attuned to his environment than most people you’ll meet. Everything around him, whether it be a passing parking lot or a CD some stranger handed him outside a show, influences his thinking in some way.

If Beck is chameleonic, he is certainly adaptable. On the bus, watching old country-music videos with his band, he’s one of the boys. During soundcheck, funkily waving his hand and thrusting out his neck to his band’s funk vamp, he’s a B-boy entertainer. And when he picks up a new guitar or drum machine, he’s a dedicated musician, intently picking his way though Delta blues songs or hip-hop beats. He is, as drummer Joey Waronker puts it, “the most complex person I’ve ever known.”

Houston

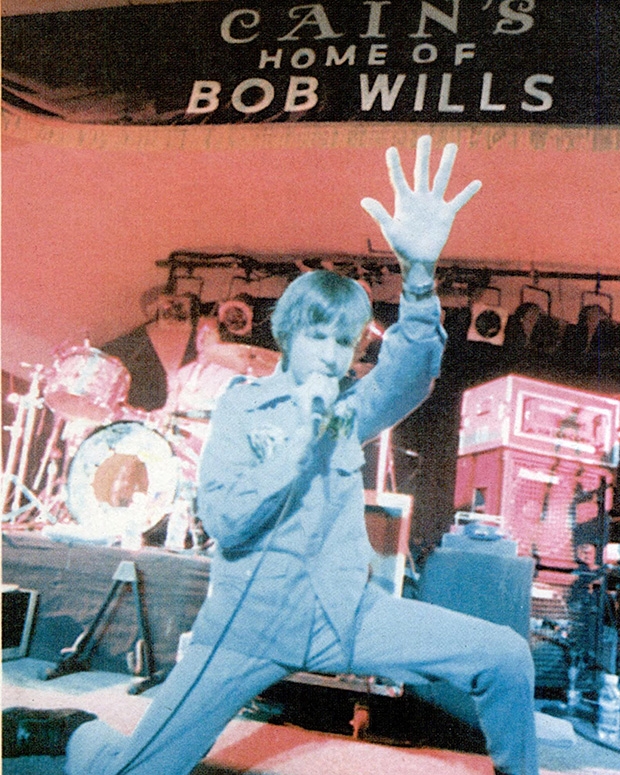

It’s Monday night, and the streets of Houston are completely empty except outside Numbers, where a line stretches the length of the club. Beck is just about the only thing happening in a 100-mile radius. And though he may have a reputation for sloppy, improvised, free-floating performances, on this tour Beck works hard for the money. Backed by a tight four-man band, he break-dances, does the electric slide in unison with his guitarists, jumps in the air and lands in a split, even gets down on his knees and begs. Though far from well, Beck still kills.

Later, on the tour bus, Beck nonetheless apologizes for what he deems an interior performance. On the VCR, the band is watching a videotape by DJ Swamp, an Ohio kid famous for ending his set by smashing his records into pieces and cutting his chest up with them. This particular video is personalized for Beck, with Swamp mixing and scratching (though not mutilating himself with) tracks from Odelay.

Afterwards, Beck and I move to the back of the bus to exchange pop-and-lock break-dancing moves and discuss the show.

SPIN: Last night, you did this move I always see in Jackie Chan movies, where you’re on your back on the ground and you flip yourself up to your feet without using your hands.

BECK: I get all my moves from Hong Kong movies, Mexican TV, and Arabic TV. They have really good moves on Arabic TV, especially on the pop music variety shows.

Do you know how to do the move where you sort of pop out each joint in your arm like this? [demonstrates]

You’re good, man, you’re actually good. That was the shit right there. We should have brought you up for a little guest popping and locking. I think I did that one tonight, didn’t I? You’ve got to do it real jerky. That’s the thing people don’t know: The stiffer and more awkward you are, the funkier you are. It’s this weird inverse-funk thing. If you look at the funkiest dancers, their upper bodies are totally stiff while another part of their body is doing something else.

That’s funny, because people usually think they’re just supposed to relax and feel the beat.

Yeah, but that’s not funky at all. Tightening up your body, like this, and being real jerky, like this [he shows how, sending a wave down his torso], that’s the funkiest.

Did you think of putting together something like a soul revue with horns and everything for this tour?

Yeah but I’d be afraid of it becoming too much of a parody. i’m sure there’s some people who think that already. But to me it’s not at all. It’s pretty sincere. There’s a sense of humor to it. But any good music has humor in it.

I noticed that backstage at Adam Yauch‘s Tibetan Freedom Concert in San Francisco, whenever someone asked you for an autograph or a picture, you would try and go about it in the most creative and humorous way you could.

Yeah, otherwise I’d feel like I was going through the motions. That’s just my instinct: to get away from the cliché. Or to take the cliché and exploit it and blow it up as intensely as possible. But that can get you into the territory of parody or kitsch. It’s really easy to do that. To do something that has some personality, some modesty to it; to do something sincere and direct, not cloying or phony, that’s the challenge.

So much of this age group or generation–and even I’ve been guilty of this in the past–takes something that’s ’70s and twists it around, either making fun of it or embracing it. There’s not a lot of direct, inspired stuff. Sure, music always feeds off itself and its past, but there’s not a lot of commitment. There’s always this snatch of. “We’re just kidding, we don’t really mean this.” It’s this continual need to goof on something our parents did or that we did ten years ago. That’s something I would really like to move away from. That’s why I was initially attracted to folk music, and ultimately hip-hop. It’s so potent. It has possibilities.

Didn’t you used to cover Ice Cube in concert?

That was around 1991, which was when I did “Loser.” I started thinking that somehow the hip-hop and the folk thing could work together. I loved playing straight old folk songs, but in rock clubs the environment didn’t really connect with that music. Other bands were doing noise stuff, experimental stuff, jazz, and hip-hop. And all that started filtering into what I was doing.

If you were locked in a room with a drum machine, how long could you stay in there without getting bored?

I don’t know; that’s a good question. When I was recording Odelay, I’d be in there for 18 hours. If you listen to the album, some of the songs and the structures seem really basic and traditional, but there are all these sounds going on in the background. I would spend forever on those. And when i had an idea for a sound, if I couldn’t play it on an instrument I’d try to do it on my voice. You go to extreme measures to come up with the right thing.

When we talked backstage at the Tibet fest, you said you liked to test out new songs in your car after you’d recorded them.

Yes, because the studio is such an insular environment. You have to take a song out and see how it holds up as a soundtrack to the world passing by. My whole approach to recording is more along the lines of something visual, looking for that sense of compositional balance and different colors and textures.

We have to work really hard to bring it off live, because something like “High 5,” that’s straight-up studio experimentation, a deconstructed song. To make it flow live is touch. But that’s what i”m shooting for in general: to take all these disparate elements and make it flow. People say that what I’m doing is like switching channels on the TV. But I don’t really look at it like that: I look at it like it’s integrating the flux and the chaos and making something substantial from it. It’s not about randomness, but taking that randomness and giving it some body. It’s not really channel-surfing. It’s more letting a batch of weeds just grow. Foliage. As if nature is just organizing, shaping, and molding this thing.

I’m always perceived as the kid who’s impatient and wants the next thing. Maybe it’s my fault. I’m definitely still developing what I’m doing. I’m feeling my way around, trying to get to that fluid place. Maybe it’s a little crude and unformed right now. There’s lots of people who need logic and structure to really move forward. But I need a jungle to find my way out of.

Do you have any idea what you’re going to do for the next record?

I think I want to do some stuff with more instrumentation, expand that a little. I don’t know, it’s all about getting in there and getting a rhythm and letting it come. Definitely the hip-hop stuff just keeps growing. I though it was just “Loser” and “Beercan.” That stuff on the first album, those were just experiments. They weren’t premeditated at all. With this album, I really found myself in this place where I knew the song was a hip-hop song. For me it’s the most challenging thing, so of course it’s the most interesting. And the deeper I get into it, the more addictive it is. The form is really conducive to experimentation. There’s only so much you can do with a country song or a hard-rock song. So I guess I’ll just be looking for more possibilities.

It would be cool to merge hip-hop with something that’s really arranged and come up with–

–with something hard and disgusting. That’s what we’re jockeying for these days.

Austin

Beck’s concert in Austin is the kind that makes a band superstitious. Everything about it is bizarre: There is a confused-looking man in a wheelchair crowd-surfing, passed wheel-to-hand to the front of the stage; during “High 5” a ten-year-old no one seems to know dances on stage as if he’s part of the band; in the middle of Beck’s acoustic interlude, he is pelted in the face with ice; and backstage after the concert; a rat drops off the rafters and onto the head of rodentphobic drummer Joey Waronker.

Back aboard the bus, the band–keyboardist and table player Theo Mondle, guitarist Smokey Hormel, bassist Justin Mendal-Johnson, and longtime Beck pal Waronker–commiserate over the weird goings-on. Free time on the fully equipped luxury liner is most ofter spent exposing one another to new music, videos, and ideas (there were no drugs, alcohol, or groupies consumed or even craved during the days I spent with them). To kill time en route to Dallas, a Scrabble game ensues. There seems to be a theme not just to the words Beck strings together (“savior,” “God,” “sin”) but to the entire game (“child,” “molest,” “jeers”). For bonus points, Beck spins a story about Michael Jackson using only the words on the board. Inspired by this rush of creativity, the idea is proposed that instead of a straightforward question-and-answer session, Beck and I would engage in some word games (exquisite corpses, free association).

But as much as he loves those games, Beck declines: “I think we should just talk. People always come into an interview and try to do something different or unusual because they think I’m off-center.”

In the back of the bus this afternoon, however, he is talked into one brief game.

I picked up a newspaper review of your show in Houston. Guess what overused word was used to describe you?

Oh no. They probably said something about how I do really bad Elvis moves. They really think I’m doing Elvis, but it’s not Elvis at all.

They didn’t mention that.

Was it “wacky”?

No, though they might have used that.

“Slacker”?

No, it’s a word that’s used almost exclusively to describe you. I’ll give you a clue. When you played in New York, you changed the chorus of “Asshole” to this word because you said it was just as offensive.

Oh, “Manchild.” Of course. I started substituting that because every review I’d pick up would say “manchild Beck.” What do I have to do? I’ve got hair on my chest, you know. I’m 26. I mean, granted, I look young. I always take it as a little disrespectful. It’s like I’m not to be taken seriously.

How do you want people to perceive you?

Human nature says that you don’t want to be categorized with Beck stamped on your forehead and sealed in hot wax. I’m just a musician that certain people seem to like. I don’t need all the attachments: I don’t need the slacker thing, I sure don’t need the retro or kitsch culture-loving thing. It’s constantly frustrating–and sometimes hilarious–supposedly being this person you’re not. But maybe I’d like to be taken a tiny, tiny bit more seriously. The records aren’t all wacky or silly nonsense, you know.

Don’t you think that by billing yourself as just Beck as opposed to Beck Hansen, you are indulging in a little self-mythologization? It’s like you’re trying to create a different from your true self.

That always turns me off. I hate that. I wanted this album to be Beck Hansen. If you look on the back cover, in the lower-right-hand corner–they didn’t want to put it on the front cover–it says in really tiny print, “Hansen.” It’s kind of too late to change, though.

Wasn’t it your choice originally to be billed as “Beck”?

Actually it started when I was playing open-mike nights and small gigs. They would write out the bill and they’d only remember my first name and never bothered with my last name. Beck was easier to remember than Beck Hansen. But there was a while when we were putting out Mellow Gold where I was like, shouldn’t I be Beck Hansen? I just didn’t think that it would matter, that anyone would care. Had I known…

You’ve also become this strange sort of sex symbol. But when I talk to people who feel that way about about you, they say that they’d be just as happy to get stoned with you as sleep with you.

Oh yeah, definitely. It’s silly. People think that drugs are a big part of my identity, and they really aren’t. I don’t need drugs to be creative. Taht’s not what my music’s about. It’s just a creative crutch. There are aspects to the music that have something to do with disorientiation, but it’s more about disorientation in modern life and our culture.

That makes sense, because in Odelay, a lot of the songs–”Famshackle,” “Derelict,” “Sissyneck,” “Readymade,” “Jack-ass”–are about lost, lonely characters out of place in society. Having been on the road with you, I wonder how much of that is a result of the constant touring and the sudden success.

Well, there was a lot to deal with. But I was determined not to let Odelay turn into something dealing with the “demons of celebritydom” and all that nonsense. It’s a very heavy thing, but you get over it. There are so many people out there who are going to make you feel like you don’t ever want to pick up a guitar again. Everywhere you turn, there’s somebody saying “I dig what you’re doing” and then you turn around and there’s a few other people saying you don’t deserve to live.

What I really wanted this album to be was celebratory, to be all about what I love about music, which is the blast I had for two weeks recording stuff for Mellow Gold, when everything was still new to me. It seems like a cliché to use your second album to grapple with the harships of fame.

Let me ask you about some of your lyrics, like that line about spreading disease across the land in “Hotwax.” What’s that about?

It’s like spreading the funk. When you come to our shows, you catch it, catch the disease.

Older musicians used to use that analogy a lot, but younger musicians never do because it has such as bad connotations with AIDS and all.

Yeah, yeah, I know. But you’ve got to take it back. I like the older sland and outmoded colloquialisms. I always try to stick a few in. There are a lot of those in traditional and folk songs: certain turns of phrases that have been lost from modern-day discourse. The old B-boy terms are really good: We had one of those how to break-dance posters, and it had a glossary section with definitions of all the B-boy terms. There were some amazing ones that I hadn’t heard in 15 years.

I liked what you were saying backstage about how you were influenced by the way Japanese people translate English.

Any foreign language. I grew up in a neighborhood where English was the second language because people spoke Spanish. I always loved that reinterpretation of language. I did this thing in Scandinavia where i took the most horrendous words–they have these 13-syllable words, concatenations of consonants, double t‘s and x’s and crazy things–and I put all of them together and had somebody translate them for me. And they were way better than anything I could write.

I definitely want to experiment with that chance operation [John] Cage thing about taking away your own instincts and letting the music just be a true expression, not colored by personality. I wouldn’t do anything like that for the sake of doing it; it would have to have some flavor to it. I think you can have a system or a plan, but ultimately the thing that’s going to be interesting is the unintended, where all the machines break down, the mistakes.

Have you done anything that conceptual in your lyrics?

No, I haven’t. You could look at some of my lyrics and think it’s a bunch of random gibberish that I made up off the top of my head. But it really isn’t at all. I couldn’t sing it if it didn’t mean something to me, if it didn’t realte to some experience or some running joke I have with a friend. Even if other people don’t really get them, still there’s this sense that it’s real.

Let me ask you about that line on Odelay: “Rocking the plastic like a man from the Catskills.” I have a few theories about what that could mean. It could mean charging a lot…

Yeah, using a credit card.

Or it could be about rocking on a microphone.

Sure. The microphone I sing through is made of plastic. I could be rocking the plastic that way, too. Ultimately, it’s all open-ended. You could say rocking the plastic as an emotion even. Or rocking plastic as almost anything you use to drink out of or sleep on or drive in. I like words that have such a presence in our lives that they’ve taken on a personality of their own.

Plastic is just one of a few words that pop up a lot in your songs: garbage, beans, plastic, cans.

Yeah. I try not to do that too much, but I can’t help it. “Mind” keeps popping up too. That’s just a good word to say: “mind.” It’s like that line “Devils’ haircut in my mind.” If you said, “Devil’s haircut in my soul…in my kitchen.” No, it doesn’t really work. Certain words are more musical.

Do you consider yourself a perfectionist?

Not in an anal/cleanliness way. That’s what I tend to think of when I hear “perfection”–someone who doesn’t want a hair to be out of place. The hairs need to be out of place, you know.

Dallas

Becks’ publicist pokes me on the shoulder: “Beck wanted me to find you and ask if you’d pop-and-lock onstage with him.”

It’s too late to RSVP. Beck is already onstage. And though the Dallas Bronco Bowl is basically a Chuck E. Cheese-style entertainment complex with a baby arena attached, it is also the site of one of Beck’s finest concerts in weeks. He is in rare form. After a loud and funky “Beercan,” Beck staggers to the microphone: “Dallas, I think I funked too hard tonight.” Then he collapses. His bandmates look around, confused and concerned, then carry him off the stage. In the meantime, one of his booking agents nervously rushes backstage, unaware that it’s all just a salute to James Brown-style showmanship.

Towel draped around him, Beck is brought back on stage or an encore, propped up by his bandmates. He vallantly throws off the towel, tosses the crowd an I’m-gonna-give-you-the-last-drop-of-funk-I-have look, and performs a brilliant outtake from Odelay, “(I Wanna) Get With You” (“and your sister Deborah”), a bedroom R&B slow jam that he emotes in a lover’s falsetto.

When it’s over, two banks of colored disco lights start flashing, and the band launches into a rousing “High 5.” After the Schubert break, Beck steps up to the microphone: “Dallas, I want to introduce you to a good friend of mine: Neil the Human Robot.”

Before I have time to wonder if I should really be messing with the tour of the year, Beck’s guitar tech pushes me onstage. I walk directly in front of the disco lights, blowing the crowd kisses to bolster my confidence. And they’re actually cheering madly, necks craned as if I’m part of the roadshow. So I run through the few pop-and-lock moves I learned in high school. Beck, standing three inches away from me, starts doing the wave with his arms. I pick it up and we pass it along, back and forth, Krush Groove style. He leaves, and bassist Johnson walks over. I touch my chin with my fingers and turn my head robot-like towards him. We pop-and-lock together.

Afterwards, the band surrounds me. “That was the funk,” Beck keeps saying. “You’ve got the funk.” More important, I got Beck’s point from our conversation about parody. Though break-dancing isn’t something a white boy in the ’90s normally does on stage, I wasn’t doing it sarcastically. It was simply the movement the music required. It wasn’t about being nostalgic or refential either: It was about being appropriate and instinctual. And this is Beck’s main qualification for greatness: not his genre-compressing songs or his deft wordplay but his good instincts, and the way he follows them, no matter how far away from musical convention they take them.