Twenty years ago this month, rapper Nasir Jones introduced himself to the world with Illmatic, a masterful debut album that offered a wistful yet hard-edged look at life inside New York City’s Queensbridge Houses, the largest public housing project in North America. Illmatic wedded clear-eyed, street-level reportage on the city’s crack epidemic to richly musical loops and no-bullshit beats crafted by a murderers’ row of respected producers that included Large Professor, Gang Starr’s DJ Premier, A Tribe Called Quest’s Q-Tip, and Pete Rock.

The story of Illmatic is a quintessentially American one: A young man uses his raw talent, tireless work ethic, and enviable connections to rise above his modest upbringing. It’s a narrative arc examined to powerful effect in Time Is Illmatic, a new documentary that details the forging of Nas’ musical career and iconic debut, and also explores the social and economic circumstances that informed the record’s alternatingly world-weary and hopeful point of view.

“The things that influenced Illmatic and influenced Nas as a young boy coming of age in America to create Illmatic are still relevant today,” says Erik Parker, 42, the writer-producer of Time Is Illmatic. Parker says he was originally inspired to make the film back in 2004, when he wrote a piece for VIBE commemorating Illmatic‘s 10th anniversary. “It felt like you couldn’t do enough justice to it in print,” he says. “I knew there was such a bigger story there.”

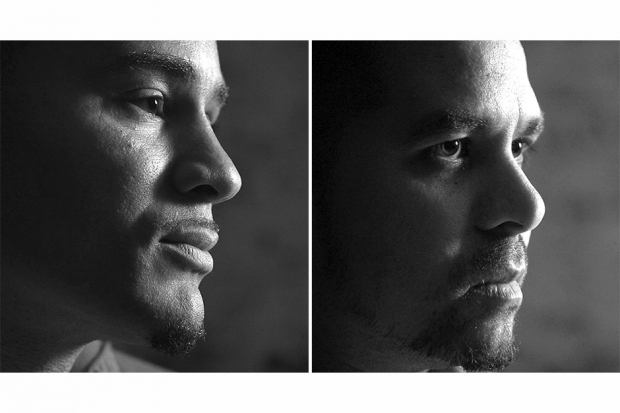

According to Parker and his 42-year-old director-producer partner One9, that “bigger story” involves the voices listeners don’t hear directly on Illmatic. With his inaugural LP, Nas nodded to his family’s history (his jazz-musician father, Olu Dara, supplies horn on the track “Life’s a Bitch”) and spoke for those who too often go ignored by society, most notably on the epistolary yarn “One Love,” which plays out a correspondence between Nas and a friend serving prison time.

Also Read

Every Nas Album, Ranked

Time Is Illmatic serves as a worthy companion to Nas’ 20-year-old hip-hop landmark. The film features interviews with Nas, his loved ones, his collaborators, and delves into his early life, but also goes back further, contextualizing the construction of the Queensbridge Houses, as well as Olu Dara’s own childhood in Mississippi. Release details are still being sorted out, but the doc recently opened the 2014 Tribeca Film Festival with an April 16 premiere at Manhattan’s Beacon Theatre. After the credits rolled, the projection screen rose upward and disappeared from view, allowing Nas to take the stage at the Upper West Side venue and perform Illmatic in full. Days later, SPIN spoke with Erik Parker and One9 about their film and Nas’ New York state of mind.

There has been so much written and said about Illmatic over the years. What separates Time Is Illmatic from that other coverage?

One9: When it comes to Illmatic the album, you’re looking at something that resonates to your soul — to your gut — whether you grew up in hip-hop or not. For me, personally, when I first heard [Illmatic], it blew me away. I never heard anything so lyrically gifted and sonically raw. I was doing artwork — graffiti art, street art — at the time, and I really think I listened to this almost everyday when it first came out. Like, back-to-back, rewinding it, playing it again. What we thought our movie would do was capture the honesty, the storytelling. Illmatic is really about people in his neighborhood: the people that he surrounds himself with, that he grew up with, who are locked up, dead, missing. The people that are gone. And he became a voice for those people. What you can get in the movie is that real intensity, that real emotion that you may not get in the written word. It’s not from the outside looking in. I’d say our movie really starts from the inside looking out.

Erik Parker: One of the things that we really wanted to make sure stood out with this film is that Illmatic is not about just Nas and what he saw outside of his window. It’s about the people he saw outside of his window, the conditions he saw outside of his window, and how he got to that point. I’m not saying it hasn’t been said. I think a lot of times what happens with Illmatic is journalists and critics and people who look at the music, they sometimes — this is not a criticism of them, this is what I see it as — they sometimes are in awe of the poetry that Nas spoke on Illmatic. And a lot of times, their analysis has stopped at the poetry and how great it is, because it’s truly great. And you can spend years just dissecting the poetry of Illmatic. I think what we were hoping to do is move beyond that, and look at the conditions that create the poet.

There’s a scene where Nas’ brother, Jabari “Jungle” Fret, looks at a photo of Nas and other people from Queensbridge that was taken by famous photographer Danny Clinch in 1994. Jungle says that pretty much everyone in the photo excerpt for Nas is dead, in jail, or just recently out of jail. And then you cut to an interview segment with Nas reacting to that, and he’s speechless.

Parker: That’s a very powerful moment. It kind of drives home one of the main themes of the film, and also of the album. You have this guy pointing out all these friends who didn’t make it, who were sitting on that same very bench, who came up in those same projects, who breathed that same air, who didn’t become Nas. And the reality is that most people don’t become Nas. Some people will overcome all of their obstacles despite the odds, and they do it with help. But what about the other people who didn’t? You can’t truly, fully understand or appreciate Illmatic, or appreciate Nas and what he did on that album, without trying to understand the predicament of the people that it was representing.

One9: Yeah, that was an amazing moment. It was spontaneous, really. We shot Jungle in Queensbridge and one of the last things was to talk about these people in the photograph. And he looked at it and was shaking his head like, “I can’t believe what I’m about to tell you.” And he started with the youngest ones [in the photo], the babies. He was like, “He’s doing 25-to-life, he’s locked up doing life.” I was like, “Wow, this is tragic.” When we sat down with Nas, he was in the studio in L.A. We played [him] that Jungle [clip] and we just wanted footage of his reaction. He didn’t know exactly what happened to all of his friends or the people on that bench. It was a hard moment. And that to me really sums up a lot about the pain of Illmatic and Nas’ voice. Nas’ lyrics become, like Q-Tip says, “Hope.” If it wasn’t for music, Nas says, “I wouldn’t even been in the picture. I wouldn’t have been on that bench. I might not have made it out.” That to us really sums up what our film is about. He becomes that voice for those who are not here anymore. And he still represents that.

It’s great that you gave some screen time to Olu Dara’s background and had Dr. Cornel West discuss the history of Queensbridge, because those elements are really intrinsic to the record.

One9: The few times that we’ve been through [Queensbridge], you feel a lot of love in the community. You feel a lot of pride. You feel a lot of lives change for better or for worse. And during the time period [of Illmatic], it was crazy for [Nas]. You had the crack epidemic — drugs and violence were at an all-time high. Nas use to talk about, “We all had guns.” All of his friends carried guns. It was like how other guys would carry a book to school. It was just that crazy. People don’t really understand where Queensbridge is, what it means to New York, what housing projects really mean to New York. We actually had that section a lot longer but we had to condense it. But we wanted to give a little bit of insight. And Cornel West was just incredible to really break things down, from the G.I. Bill, to how land was being allocated at the time. What happens to the family once jobs go overseas and the drug invasion comes and Reaganomics kicks in? How does that affect the Jones family and, more precisely, how does it affect Nas? We wanted to give that backstory, to really give you a better look at where Illmatic came from.

Did you uncover any surprises about the album in your research?

Parker: As an editor at a magazine, I’ve deconstructed records based upon how they were made, and what took place in the studio, and the little details that went into the making of records. We kind of limited that for this film. What we took away from all of our research and time is that the making of Illmatic started well before he got into the studio. It was a culmination of life experiences, world experience, his friends, his family legacy. It wasn’t built in one generation. That’s the takeaway. But what happens in music is that a lot of times, what’s done in the past is not acknowledged in the first album. For example, you might hear an album from an artist, and that artist obviously wouldn’t be where they are at that point without a great deal of help and commitment. However, the album may not reflect that; may not tell the story of that; may not have the depth, the context, that allows you to point to those influences. What Illmatic did was it showed the culmination of generations, by even adding Olu Dara playing horn on “Life’s a Bitch” — the bridge to his Mississippi roots, to jazz, to the blues.

At the premiere, after Nas performed, he thanked everyone and mentioned that he was originally hesitant to get involved in the project.

One9: Initially, it was such a raw look at his life. We’ve seen the evolution of Nas through the course of making this film. By that I mean he was somewhat guarded at first about telling his story, his family’s story. I’m sure anybody would be. We kind of started this project on our own, out of our pocket, as a passion project. We interviewed his father first, and that was an amazing interview that lasted about three-and-a-half, four hours, and it really gave us a look into the Jones family history. We got a chance to hear about what it was like for Nas growing up, for his brother, and what music and the culture was. And from there we took it on our own to interview [DJ] Premier, Pete Rock, AZ, a bunch of other people, and actually pitched a trailer without Nas to Nas’ management. And we sat down with his manager and he actually brought Nas to the dinner table. And we talked about it. He looked at it—he was very impressed. But again, he didn’t know us, so he said, “Keep going, see what you guys got.” Once we had more scenes cut together and more rough cuts, then of course we just needed the man himself. We needed his voice to tell his side of the story. And we eventually got a grant for it. So we reached back out to Nas and said, “Listen, we can make this a reality. We’d love to finish it up.” So he came in and looked at little clips, rough cuts, and four hours later, he didn’t want to leave. He was like, “Man, this is amazing, let’s definitely do this.”