Athens, Georgia, 1985. The acid had lost its come-hither bouquet and the speed had snapped everyone’s nerves like twigs. The run-down Victorians weren’t such a steal anymore and the days of buying an armful of thrift-store dresses for a quarter were long gone. Two years before, People magazine had run a photo of a group of obscure local musicians gathered around a Confederate memorial downtown to illustrate an article about America’s so-called rock renaissance. Considering that the South was where punk and new wave had been met, at best, with piss-off slurs, this was a little hard to fathom. But now, Athens bands were multiplying at a dizzying rate, and wannabe rockers were even making pilgrimages to this bucolic college town.

One sunny afternoon, I was driving near Barber Street (where penniless bands once flopped in “Munsters” houses, as Pylon drummer Curtis Crowe put it) and a friend in the passenger seat pointed out the window and casually commented: “You know, Pete Buck just bought a house over there.”

“What?!” I exclaimed.

“No, it’s true,” he answered with a slight smirk. Like many, he’d grown weary of the scene’s self-image as a bohemian arcadia, full of demure aesthetes, untainted by ambition.

Also Read

Kurt Cobain Forever

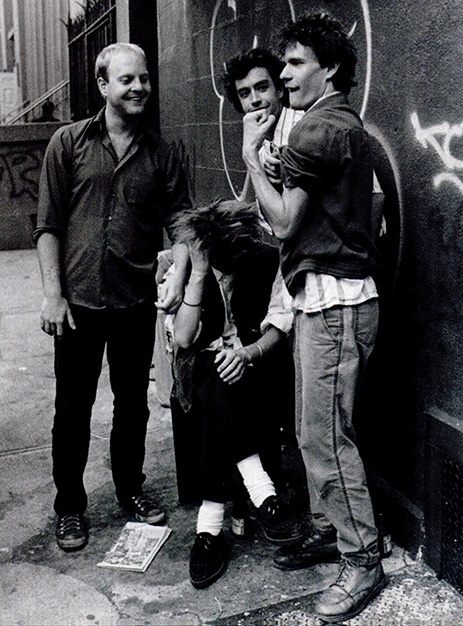

But I was flashing back a few years, to when Buck was just another unwashed face in the crowd: a babbling record-store clerk who gave me the hard sell on Pere Ubu, the New York Dolls, the Velvet Underground, and racks of other older bands that he touted as more “punk” than the hardcores I worshipped like Black Flag, Circle Jerks, and Dead Kennedys. To my surprise, he was also in a local band called R.E.M. (lower-case, blurry letters on a yellow flyer I pulled off a telephone pole) who played a cool black-and-white Rickenbacker guitar with an impressive panache for someone who clearly couldn’t even fake a solo. R.E.M. weren’t incensed punks or stylish, wound-up new-wavers, and even though they played familiar covers (“Gloria,” “Toys in the Attic”), they never really rocked. Instead, they sketched out shadowy moods in a swirl of twitchy melodies and rhythmic turnarounds. Rag-doll singer Michael Stipe would convulse, withdraw, and collapse into an introverted, swaying trance that, in retrospect, was a more languid version of Joy Division’s Ian Curtis. But at the same time, I thought he was the antithesis of every rock singer I’d ever seen. His phonetic lyrics, sung in a reedy near-drawl, made no apparent sense, but his voice felt totally original — intimate yet enigmatic. And he gave off a sexuality that had nothing to do with rock’s usual your-girlfriend-wants-to-fuck-me bombast.

R.E.M. soon began to tour — visiting towns largely unmarked by punk (from New Orleans to Memphis to Albuquerque), in addition to New York, Boston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Their shows were famously intense, whether playing for a bar of hostile drunks in Detroit or four curious hardcore brats in Birmingham. Buck became a true-believing advocate for scores of new underground acts — Minutemen, Jason and the Nashville Scorchers, Let’s Active, the Dream Syndicate, etc. And gradually, as more bands toured widely, an outsider circuit emerged based around independent labels and record stores, college radio stations, and fanzines. As a result, throughout the ’80s, strong scenes formed in places almost as unlikely as Athens — Minneapolis, Austin, Seattle, Chapel Hill.

This may not seem like a righteous cause today, but at the beginning of the ominously moralizing Reagan era, you took what you could get. For just about any kid who wasn’t an aspiring Christian careerist in khaki duck pants, the country could seem heartless and remote (there was no Internet-driven sense of community), and the music business, with its craving for baroquely produced, drum-machine Euro-pop, seemed just as inaccessible. Hardcore punks raged against the U.S.’s cultural and political depravity, but this new group of underground bands (like R.E.M.) had an oddly traditional, even patriotic, chip on its shoulder. It was as if they were saying, “There’s so much great music here that’s being ignored, why can’t people just wake up and appreciate it?” The Los Angeles punk poets X stated it plainly: “Will the last American band to get played on the radio, please bring the flag?”

R.E.M., in its way, made the country feel less foreboding and more inclusive, replacing hardcore’s iconoclasm with a warm invitation to less-hip kids who didn’t live in California or the northeast. “When I was 15 years old in Richmond, Virginia, they were a very important part of my life, as they were for all members of our band,” said Bob Nastanovich of ’90s indie-rock doyens Pavement. “They were this uniting force. People who liked Black Flag liked ’em and people who liked the Dead liked ’em. They were the first [underground] band that the frat guys looked at and didn’t say, ‘Oh, let’s beat up some fags.'”

R.E.M. weren’t selfless ambassadors, though; they were also role models because they succeeded. From early on, the band made sure business was taken care of so that it didn’t interfere with their music. In fact, ever since, people have talked about, and envied, the so-called “R.E.M. Model,” a series of basic, easier-said-than-done career moves — hire a manager and lawyer as soon as you make any money; tour like a circuit preacher; sign to an “independent” label that has major-label backing; move to a major only when you’ve built a substantial following; insist on “creative control” (you make decisions on the producer, the single, and the video); split the money fairly among the band members; don’t fear the power ballad.

By 1985, R.E.M. were about two-thirds of the way through this process, but it was already obvious that their music was paying off, and that their future was secure. They’d shown how far an underground, punk-inspired rock band could go within the industry without whoring out its artistic integrity in any obvious way. They’d figured out how to buy in, not sell out — in other words, they’d the achieved the American Bohemian Dream.

A couple of years later, the anarchic Texas hardcore band the Butthole Surfers performed an incendiary version of “The One I Love,” R.E.M.’s 1987 attempt at a prosaic pop single, while singer Gibby Haynes devilishly burned dollar bills onstage. Haynes was obsessed with R.E.M. — in fact, he’d briefly moved his band to Athens in the mid-’80s, partly due to his curiosity about their mythos. It amazed him that they’d maintained such an aura of purity, despite consistently burnishing their music and hardballing their business operation (R.E.M. Inc. is now one of the most powerful companies in Athens). As a Trinity College accounting grad turned lawless, shit-slinging prankster, Haynes was careening in another direction — his band’s name couldn’t even be mentioned in a newspaper — and he didn’t trust how efficiently the Model was humming. Didn’t there have to be some deal with the devil that we didn’t know about?

Or maybe it was just envy (the Buttholes eventually signed their own major-label deal years later). But as I was driving on that sunny Athens afternoon, pondering Pete Buck: Homeowner, I could relate. How did R.E.M. pull it off? And was there something wrong with the rest of us if we couldn’t develop our own plan for making a living off the scene?

As I gazed dumbly ahead, thoughts racing, my friend turned to me, his smirk now suspiciously deadpan. Then he delivered the kicker.

“You know, he’s got a pool, too.”

By the mid-’80s, the raw sprawl of post-hardcore “underground rock” was coalescing, and after R.E.M.’s success, a number of bands started to think that they could also buy in. Major-label reps were showing more interest, and it seemed like a new generation might be ready to have its day. (It’s no coincidence that SPIN published its first issue in May of 1985, though by putting Madonna on the cover, we were still hedging our bets.) But like the brilliantly unhinged Arizona burnouts in the Meat Puppets, many of the underground’s “stars” did live lives that could seem idiotic and buffoonish, and performed brain-raking music that genuinely freaked people out. Business was not their métier. Still, in 1985, the most incorrigibly ill-behaved rock band in America, Minneapolis’ Replacements, signed to Sire and released their major-label debut Tim, a perfectly ragged collection of anthemic pleas written by singer-guitarist Paul Westerberg. If the rock masses embraced the ‘Mats, maybe a change was coming. But Tim was a commercial stiff, as was X’s Ain’t Love Grand!, a last-gasp by the exquisitely corrosive underground elders to domesticate their sound. Former hardcore punks Hüsker Dü (Minneapolis natives like the Replacements), recorded their major-label debut, Candy Apple Grey, for Warner Bros., a 10-song stunner of feverish punk-pop headtrips, but it never earned a nod from commercial radio. The moment’s hopeful ambition faded. And in a tragic coda, D. Boon, singer-guitarist for agit-blurt virtuosos Minutemen, and possibly the underground’s most impassioned figure, died in an auto accident in December of ’85.

But this period of disenchantment would have just as permanent an impact on rock’s next ten years as R.E.M.’s crafty breakthrough. As major labels moved on to hump the L.A. hair-metal ass-party, underground rockers began to lose their craving for mainstream validation. The new role models became uncompromising label owners like Greg Ginn of Southern California’s SST, and Ian MacKaye of Washington, D.C.’s Dischord. SST, which had started in the late ’70s with Ginn’s pioneering Black Flag, was a relentless force, signing up the most significant underground bands of the early-mid-’80s — Minutemen, Hüsker Dü, Meat Puppets, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr., etc; MacKaye stayed local, assiduously documenting the D.C. punk scene of groups like Government Issue, Dag Nasty, and Rites of Spring. Both were consumed by the idea that a self-sustaining independent framework was necessary for compelling music to thrive. (MacKaye went so far as to break up his powerhouse hardcore band Minor Threat after the other members wanted to consider signing to a major label).

As this shift took place in the underground scene, a new tag for the music began to crop up: “Indie rock.” A nod to the importance of independent labels, it was the rare genre name rooted in economics rather the sound of the bands it involved. It could be traced to the early ’80s, Marxist-inspired British indie scene, where labels viewed their business arrangements — no contracts, 50/50 split of costs and receipts, the band’s ownership of their recordings — as a political statement. The American version was more individualistic than militant, and the music itself was much less self-consciously disaffected.

A classic case was Amherst, MA, trio Dinosaur Jr., who released their self-titled debut in 1985. Singer-guitarist J Mascis, though hidden behind a curtain of scraggly hair, unleashed a shitstorm of distorted riffs that could practically cave in a club’s ceiling. His songs, which sounded like Neil Young as a pissed D&D geek, were a roaring, revelatory purge. “Dino were part of this thing I saw with the later punks and hardcores — these guys who were too young to react against rock’n’roll,” wrote the Minutemen’s Mike Watt for a reissue of the band’s first three albums. “A lot of the ’70s punks were trying to be ironic and satirical about the whole paradigm of rock’n’roll… I was into a kind of ideological war, but for these guys, it wasn’t that much of an issue.”

A multitude of underground bands flourished during the latter half of the ’80s, and their music gave indie rock a creative rush that mirrored the late-’80s “golden age” of hip-hop — just substitute Run-D.M.C. for R.E.M. A band like Rites of Spring was obviously trapped in a post-hardcore malaise, but Guy Picciotto sang like he was setting himself free by ripping up diary entries in the middle of Dupont Circle, while guitarist Ed Janney looted a fakebook of melodies behind him (Rites’ sound was dubbed “emo-core” for its emotional bent, later shortened to “emo”). Picciotto then moved on to play guitar and sing with Ian MacKaye’s new band Fugazi, a hurtling blur of scratchy rhythms and open-hearted, anti-sexist manifestos. The band’s ascetic idealism — playing all-ages shows for five dollars — was almost as bracing as their timebomb-ticking songs.

In the D.C. suburb of Arlington, Virginia, Mark Robinson’s Teenbeat label was a cheekier proposition. His band Unrest mixed winsome, strummy love songs with a brash, pop-culture irony that would later become indie-rock’s defining identity (Camper Van Beethoven were the hippie-ish Northern California corollary). Unrest’s peak, the 1991 7-inch “Yes, She Is My Skinhead Girl,” a sugary ode to a punk crush, was co-released with like-minded Olympia, Washington-based K Records (K and Teenbeat were both partial to 7-inch singles with hand-made artwork, which carried a tinge of nostalgic innocence, especially as CDs became more prevalent). Known for its minimalist, almost childlike aesthetic, K was founded in the early ’80s by Calvin Johnson, whose band Beat Happening was the embodiment of the label, playing rudimentary, defiantly gawky songs about sexual coming-of-age from both male and female perspectives (Heather Lewis sang and played drums).

K also ambitiously mapped out the International Pop Underground, a network of heady indie acts — most notably Olympia singer-songwriter Lois Maffeo, Canadian folk-punk duo Mecca Normal, and scruffy Scottish romantics the Vaselines (led by singer-guitarists Eugene Kelly and Frances McKee); the culmination was 1991’s IPU Festival in Olympia, featuring Fugazi, and all-female bands Scrawl, L7, and Bikini Kill. The international indie-pop scene reached as far as New Zealand, where the label Flying Nun released records by a remarkable group of bands (the Clean, the Chills, Verlaines, the Bats) who matched fanciful lyricism with tremulous guitars.

But the most exceptional aspect of all the above bands was their distinct lack of macho posturing and objectifying lyrics, and as a result, they would inspire great numbers of women to start their own bands and labels. The prominence of so many male-female duos also gave the music a different level of complexity and a more revealing, if at times awkward, intimacy. The jangly, droning Velvet Underground-influenced sound of Hoboken’s Yo La Tengo, for instance, took on a more affecting edge when drummer Georgia Hubley tempered the feverishly boyish excursions of singer-guitarist Ira Kaplan.

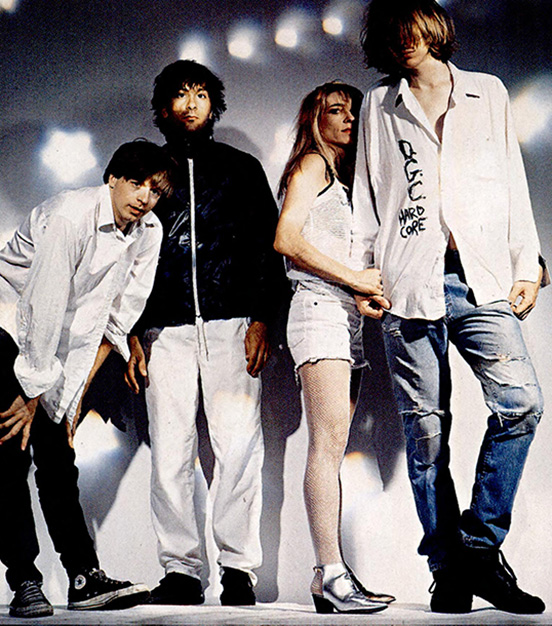

Bookending this period were two bands: Sonic Youth, who spent the pre-indie era as a cooler-than-you, downtown New York art-noise clique before developing into a R.E.M.-like presence through the mid-late-’80s; and Boston’s Pixies, who bypassed the U.S. indie circuit, first finding success for their abstract pop squall in the U.K. Both were led by male-female duos — Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore and Kim Gordon, the Pixies’ Black Francis and Kim Deal — and their music could like an ongoing 3 A.M. heart-to-heart, flipping from eerie whispers to alien croons to gnomic shouts. So when they signed to major labels — Pixies to Elektra in 1988 and Sonic Youth to Geffen in 1990 — it was an acknowledgement that indie’s reinvigorated version of rock might finally be market-ready.

But when the crossover came, it was from a scene that had little to do with the aforementioned aesthetic and social shifts (which might explain its commercial potential). Seattle had been an isolated and gloomy zone for underground and indie rock through much of the ’80s, a place where metalheads and ’70s-style rockers were still grinding it out in rainy anonymity. And the city’s important post-hardcore indie bands — Green River (which split into Mudhoney and Pearl Jam), Melvins, and Soundgarden — started by putting a punk spin on ’70s titans like Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, and Aerosmith. Though they might not have been the most progressive, Seattle’s best were ferocious live — their shirtless swagger and stomping, sludgy riffs headbanged with a shot of irony and humor.

Local indie label Sub Pop latched onto this so-called “grunge” sound, aggressively promoting and branding it like a mini-major label (even hosting British journalists, who went home crowing about Seattle as the center of America’s new rock revolution). The band who benefited the most was, of course, Nirvana, whose singer, Kurt Cobain, was a flannel-metal kid, but also loved underground punk bands (Black Flag, Butthole Surfers, Big Black) and indie rock (he said that K was his favorite record label). With the release of their second album, Nevermind (now on major-label Geffen instead of Sub Pop), Nirvana took all these disparate elements to the top of the pop charts, seemingly confirming that punk and indie music was capable of appealing to a mainstream audience (if given the right production and promotion). And in their wake, a series of bands were solicited and signed by majors.

But none would have the cultural impact of Nirvana, and few would see any financial windfall. While Cobain became deeply conflicted about the media notoriety that came with Nevermind‘s popularity (he was constantly referred to as the voice of a generation), indie artists also grew ambivalent. Was Nirvana’s success, and even Sonic Youth’s safe major-label passage, a case of “we won,” or just a pathetic grab for validation from the type of people who used to stuff “us” into gym lockers? Did former indie kids — now referred to as “alternative rockers” — really believe that major labels would bestow them with expense accounts and not ask for serious concessions? Nirvana had cited the R.E.M. Model as a way to maintain artistic integrity while doing business on a larger stage. But like Hüsker Dü and the Replacements in the mid-’80s, most other indie bands couldn’t meet the Model’s demands. And ultimately, neither could Cobain — who became disillusioned and committed suicide in 1994.

This ambivalence, and Cobain’s drugged-out breakdown, pushed indie-rock in two self-conscious directions: the “lo-fi” scene and the “riot grrrl” movement. Lo-fi devotees curled up and hid from the mainstream, favoring hissy four-track recordings and confessional, self-mocking lyrics (best represented by Sebadoh, Guided By Voices, and Pavement); an Olympia, Washington and Washington, D.C. nexus, “riot grrrl,” was overtly political, led by the bands Bikini Kill and Bratmobile and the label Kill Rock Stars. It matched a passionate, spray-the-room critique of rock and media sexism with a playfully artless attitude toward musicianship. Their best songs were like nursery-rhyme fatwas.

While riot grrrl was a radical indictment that helped lead to an actual “women in rock” surge at major labels in the mid-’90s, lo-fi was a strategic withdrawal — sincere and coy, meant to zero in on the music’s emotional core and deflate rock-star pretensions. There was a willfully ingenuous quality at the heart of lo-fi, a longing for a time before the temptations and pressures to cash in. Dinosaur Jr. had moved on to a major, but bassist Lou Barlow left to form the contentious trio Sebadoh, where he flayed himself as a needy, selfish jerk, in stripped-bare, often acoustic songs. Then there were the “slowcore” bands — Low, Codeine, Bedhead — who replayed moments of despair and isolation at ever more torpid tempos, as if to stop-focus every troubling detail. Punkish scrappers Superchunk tore out of North Carolina with the 7-inch anthem, “Slack Motherfucker,” a stirring refusal to work for anyone but themselves. And perhaps the genre’s most celebrated artist, Liz Phair, straddled lo-fi and riot grrrl, singing affectless post-feminist kiss-offs to an indie world she saw as increasingly dominated by indulgent guys.

But the bands that came to exemplify indie rock in this period, and still define the term in many people’s minds, were Pavement and Guided By Voices. A furtive collective from Northern California, led by singer-guitarists “SM” (Stephen Malkmus) and “Spiral Stairs” (Scott Kannberg), Pavement created lo-fi bedroom dramas that romanticized the misty bewilderment of college kids on the cusp of entering the adult straight world. Their free-associating lyrics over melodies that seemed embedded in the staticky fuzz of a transistor radio were a cryptic denial of alt rock’s ambition. Malkmus has a gift (like Kurt Cobain) for inside-joke aphorisms that felt like generational broadsides. On the 1992 album Slanted and Enchanted, he mused with a stricken hauteur: “I’ve got a lotta things I want to sell/ But not here, babe” and “All the things we had before/ You sold us out and took it all.” Guided By Voices, led by thirtysomething Dayton, Ohio, schoolteacher Robert Pollard, had been churning out cruddy-sounding recordings for years, but their literate, elliptical bursts of British Invasion-tinged rock never caught much attention. But with the release of 1994’s breathtakingly composed Bee Thousand, they were suddenly a mini-cause celebre, a symbol of the uncompromising, self-reliant indie artist who eventually gets the recognition he deserves.

As the ’90s progressed, indie rock became less of an oppositional cause — alternative had become a mainstream proposition, in an albeit attenuated form (Nirvana gave way to Pearl Jam which gave way to Stone Temple Pilots and Silverchair), and many of the music’s fans had grown up to work in mainstream industry jobs. “Indie” was now more of a pejorative for a sound (disaffected guitars and lyrics) and a stance (nerdy white college boys who prized their record collections). Many influential labels — like Sub Pop and Matador — cut deals with majors for financial support, and the indie/mainstream dichotomy became harder to parse. At this point, underground hip-hop more closely resembled indie rock’s ’80s ideal.

When alt rock finally collapsed into the sexually assaultive arena schlock of Korn and Limp Bizkit in the late ’90s, there was a quiet backlash in favor of more modest indie bands. These groups, unlike, say, Beat Happening, Bikini Kill, or even Pavement, had no real agenda or sense of a larger context — they just wanted to put on a good rock show that wasn’t a moronic embarrassment (a rarity at the time). The White Stripes (a male-female duo who got their first breaks opening for Pavement and riot grrrl progeny Sleater-Kinney) and the Strokes (worshippers of Guided By Voices) wrote great songs that sounded like direct tributes to other great songs. And they looked cool while doing it. In this version, “indie rock” was simply a smart aesthetic choice. Unsurprisingly, both bands enjoyed commercial success, signing lucrative record deals and giving the industry a fresh burst of energy.

Meanwhile, boosted by an economic trickle-down from alternative’s payday and the growth of the Internet, the indie/underground scene continued to professionalize. It was far easier for small labels to distribute records, and the touring circuit was lively and profitable. Artists were able to sell their songs to movie soundtracks and commercials to supplement their income and gain exposure. In effect, the indie scene was a viable career option and a major-label farm team, grooming bands for the next level. The R.E.M. Model had become the norm.

In October of 2003, singer-songwriter Elliott Smith committed suicide in Los Angeles at age 34 after a long, tortured battle with addiction and depression. Smith, who emerged from the Pacific Northwest indie-rock scene, was, like Cobain, one of the most talented songwriters of the ’90s. His hushed, wounded, folk-punk songs movingly reflected the fallout from alternative rock’s early-’90s circumstance. After releasing three indie albums (two on Kill Rock Stars) that built a moderate cult audience, he signed to the major label Dreamworks. But his inability to endure the demanding industry routine, especially after somewhat disappointing record sales, took its toll. He gradually found more comfort in drugs than music.

For fans of today’s commercially successful, blithely shambling indie-rockers — the Shins, Death Cab for Cutie, Interpol — Smith’s dilemma may be difficult to grasp, like an artifact from another generation. Sure, these bands express troubled emotions, but they never seem to be in any real danger. Listening to Death Cab’s Ben Gibbard, there’s a sense that no matter how badly things go for him, he’ll always find a soft place to fall. Is that maturity, or just the security that comes from the groundbreaking accomplishments of others? And does it have anything to do with the quality of today’s music? How you answer that question probably depends on how much you’ve invested in the indie saga, and how much you’ve been able to make its lessons pay off.