ALBUM OF THE MONTH

B.N.M. / P.D.D.G., S/T (Príncipe)

The Príncipe label’s output barely amounts to a trickle — just five EPs over the past three years — but it’s enough to confirm that Lisbon is currently the source of some of the most exciting new developments in electronic music. Príncipe signees DJ Marfox and DJ Nigga Fox tore the roof off Krakow’s Unsound festival this fall with DJ sets full of rubbery melodies and elastic rhythms drawn from kuduro, batida, kizomba, funaná, tarrachinha, and Afro-house, all enlivened by scraps of rap and dubstep. It’s the best party music in the world, but Príncipe’s new release pulls back the curtain on quieter, more abstracted sounds from the Angolan diaspora. In the process, it reminds us how little most of us outside Lisbon really know about this culture. To wit, this mini-comp introduces us to seven new names. DJ Firmeza, DJ Maboku, and DJ Lilocox represent the Piquenos DJs Do Guetto crew, named in homage to DJs Do Guetto (Marfox, Nervoso, N.K., and other pioneers of the Lisbon scene); from the other side of the city, DJ Kolt, DJ Perigoso, and DJ Noronha represent the Blacksea Não Maya crew.

What they all share in common are resonant sampled percussion, loping polyrhythms, and an exceptionally porous sense of texture; scraps of accordion and voice flutter like laundry in the breeze. The plucked electric bass and fluttering congas of DJ Kolt’s “Afrooloove” evoke darting moths and dripping faucets, and Noronha’s “Africa Congo” mirrors staccato organ melody with stuttering hand percussion and machine snares, while Maboku’s similarly pointillist “Instrumental Pe” daubs flute synths over drums that land like fat, scattered raindrops. Mobuku, Lilocox, and Firmeza’s “O Vento de Uma Verdadera Amizade” is the record’s most outwardly emotional song, with lilting accordion melodies played against lithe synth fillips and tinny brass stabs — it brings to mind Doctor Rockit’s “Café de Flore” as reimagined by DJ Mujava — but Firmeza’s solo tracks are entirely different. “Dedicado ao Projecto Príncipe” pairs jubilant shouts and yelps with wildly syncopated and pitch-shifted toms, and the shuffling “Remeche as Coisas” is a slow-motion swirl of hand drums and hiccups in 6/8 time. DJ Perigoso’s “Dia da Moka” and “Decaléé” are the most disorienting songs on the record, dissonant and soaked in echo, and recasting techno futurism in corrugated tin and pirated electric current.

Logos, Cold Mission (Keysound)

Turns out that not even grime is immune to nostalgia. It’s well established that U.K. house music is deep in the throes of a retro moment, but adherents of the so-called hardcore continuum pine just as hard for rave’s prelapsarian era — just consider Burial’s misty-eyed paeans to the post-club night bus, Four Tet’s pirate-saluting “Kool FM,” and Special Request’s back-to-basics breakbeat forays. The East London producer Logos is upfront about the sentimental underpinnings of his own music, which he described as “tracing the links between classic Metalheadz productions and early grime, […] but integrated in to a roughly 130bpm club context.” (In the press release he noted, “A lot of the album is informed by nostalgia for pirate radio grime and the sense of loss I feel for that period — 2002 felt like such a simpler time.”) Nevertheless, there’s nothing expressly retro about his strange, enveloping album, whose very structure seems inspired by the fitfulness of memory. It’s abstracted to the point of dissolution and pocked with blackouts, awash in classic bass-music tropes — breaking glass, guncocks, stubborn squarewave bass bleats, icy arpeggios — that tend to spin idly in midair, like gears that have come undone from their machinery. This isn’t due to some failure on Logos’ part: You can tell from the way his songs start, hesitate, stall out, and start again that they’re supposed to work this way. Even the heaviest beats are rendered weirdly functionless, and long stretches of shimmering synthesizers render the album’s overall effect closer to ambient music. It’s grime as Zen garden, a careful array of raked gravel and auspicious boulders and lone, green shrubs whose spatial arrangement is designed to facilitate maximum contemplation.

Egyptrixx, A/B Til Infinity (Night Slugs)

No label has a keener sense of its vision right now than Night Slugs. Few have a more original vision, either, although their signature isn’t the kind that necessarily jumps out at you. It’s not about particular sounds or rhythms or tropes; pretty much everything in their music has been done before, by grime or techno or house or ambient, but they’ve never been done in this combination. It’s a question of proportion, of focus, of texture; less what the music does than how it does it. Like recent records from Jam City, Girl Unit, and Kelela, Egyptrixx’s new album makes the most of negative space — space that he often fills with great, metallic sheets of clang, like a Foley artist in a fugue state. The opening “Axis” sounds like a grime remix of Haxan Cloak, and it just gets heavier from there. Unlike most heavy club music, though, the beats don’t dominate. Even on the technoid “Alta Civilization” and “Water,” the kick drum’s a fickle shadow of a thing, leaving buzzing synths and bell tones to bear most of the weight, and for good long stretches, the record drifts in a beatless Blade Runner haze. “My Life Is Vivid, My Eyes Are Open” sounds like Oneohtrix Point Never imprisoned in a basement grime rave; the closing “A_C_C_R” offers us a portrait of the artist asleep at his Juno 106, face mashed against the keys — until the reverie is shattered by blast-beat kicks and rapid-fire lazer zaps, reminders of the awesome and unpredictable forces that lurk beneath even the quietest moments of this intense, unsettling record.

Graze, Edges (New Kanada)

Canadian-in-Berlin Adam Marshall and Canadian-in-Canada Christian Andersen (a.k.a. XI) both hail from the same Toronto suburb, although they didn’t cross paths there; Marshall comes from techno and Andersen came up playing drum’n’bass and dubstep. The project was conceived while Andersen lived in Berlin but recorded after he returned to Toronto, and fittingly, it functions as a snapshot of the amorphous and geographically dispersed club style known as “bass music.” Somber, sullen, thick with gurgling synthesizers and plated with brushed steel, it often feels like techno, but the broken rhythms and staggering kick drums are indebted to dubstep and jungle. The tempo, meanwhile, runs slower than any of those genres, lending even more moodiness to cuts that are already equal parts melancholy and menace. The album gives up the goods only grudgingly, particularly in its first half, where metallic percussion sounds set the tonal agenda and melody is relegated to a purely decorative role. But there’s levity here, too: Beneath the stately chords and cloth-wrapped hammers of “Airror,” there’s a faint cry that sounds like it might have been sampled from MJ Cole’s “Sincere,” and “Ripley” is soft and yielding beneath its thunderclaps and flashing rotors, as evocative of Cocteau Twins as it is Carl Craig.

Ricardo Tobar, Treillis (Desire)

Like many port cities on the Pacific, Viña del Mar, Chile, has amazing light and a radiant gold/pink glow, which might go some way towards explaining the incredibly luminous quality of its native son Ricardo Tobar’s jewel-toned electronica. He got his start recording for James Holden’s Border Community label, and his own music has evolved in parallel with theirs, growing from fuzzy, bulbous, chord-heavy techno into something fuzzier, more colorful, and even more unpredictable. Squirming like an amoeba under a microscope, his debut album evokes an organic vibe similar to that of Four Tet, Daphni, and Luke Abbott. Unsteady machine beats thump spasmodically away beneath pinwheeling arpeggios and meandering modular patches, and it often feels like it could all fall apart at a moment’s notice; in “Organza,” an errant LFO threatens to derail the beat altogether. But scrape away the shards of broken kaleidoscope and the layers of melted crayon, and rave’s ecstatic pulse pumps fervently away. It’s a gut-level memory — refracted through shoegaze and Boards of Canada and top-shelf psychedelics — that smells like salt air and tastes like sunset and coral.

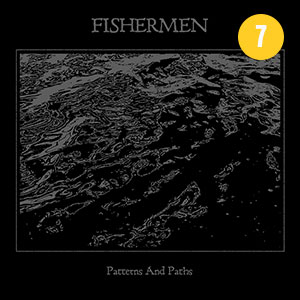

Fishermen, Patterns and Paths (Skudge)

Just going by their t-shirts, you might guess that Skudge was a metal label. Wrong: They’re techno to the core. But the debut album from Fishermen (Skudge regular MRSK, a.k.a. Martin Skogehall, with Thomas Jaldemark) definitely makes good on all that grim affect. Following a pair of EPs released earlier this year, Patterns and Paths pursues their loose nautical theme (“Scurvy,” “Torments,” “Sunken Mosque”) across sluggish, slow-mo techno, gothed-out tribal house, and old-school, Jeff Mills-style bleepery. “Greenhorn” sounds like Sleep Archive remixing Deafheaven; “Serpents” throws dancehall shouts over downtrodden Belgian rave; and “Get None” sounds like what might happen if Diplo were a Rotterdam gutter punk with a nasty lean habit. Throughout, there are enough pitched-down, tape-warped vocals to make you wonder if Fishermen’s analog delay is picking up EVP as they go crawling through techno’s shadowiest extremes.

Ben Sims, Fabric 73 (Fabric)

Ben Sims is getting it done. His Fabric mix is workmanlike in the best way: This is techno as rock quarry, techno as loom, almost Sisyphean in its slow, methodical sweep. Over the course of 69 minutes, he plows through 44 tracks, and “plow” really is the operative metaphor, with four-to-the-floor pulses laid out like furrows, crumbling at the edges and bristling with debris. Turning up scraps of acid and glinting tri-tones as it churns, the mix is more varied than it might appear at first; that 128-BPM pulse is ceaseless, but the real action comes in slower, subtler gestures, with passages shifting and colliding like gusts of rain. Occasionally, a voice cuts in: Alden Tyrell’s “Wurk It” urges dancers into a loopy delirium early on, and Sandrien’s “I Left My Girlfriend in a Club” lends a moment of voices-in-your-head unease. And Sims isn’t afraid to grab us by the lapels when he feels it’s appropriate: Launching into Marcel Dettmann’s “Corebox (James Ruskin Blueprint Mix),” one of the mix’s early highlights, he even lets rip with a vinyl spinback, as though reminding us that “no nonsense” doesn’t have to equate to “no fun.”

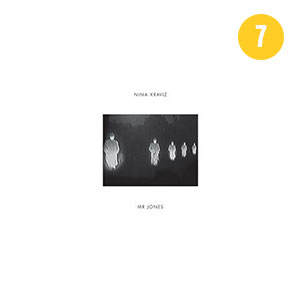

Nina Kraviz, Mr. Jones (Rekids)

One possibility went overlooked in all the bubble-bath hubbub earlier this year: Maybe Nina Kraviz likes a good soak because she’s really, really cold. Her new EP for Rekids sounds chilled to the bone. Its seven tracks (10, including alternate versions, totalling nearly an hour-and-a-half of music) amount to some of the wintriest, most desolate house music of the year, looping spoken phrases and wordless vocals over brittle, desiccated drum tracks and filling in the emptiness with eerie bleeps and barely-there chords. Drawing layers atop translucent layers, the tracks come together like lines traced in a frosted window; their numbing repetition suggests Ricardo Villalobos’ “Fizheuer Zieheuer” in a cryogenic state. (In “Remember,” she even chants, “You’re so cold.”) There are nods to warmer climes — “Black White” features “Beau Mot Plage” chimes and a vaguely Dem Bow-ish beat, and it begins with a snippet of stoned pillow-talk between Kraviz and a male speaker, who banter huskily about oysters and pearls until she throws a bucket of ice water over the proceedings. When the man professes to prefer mussels, she reprimands him, “They eat shit, you know.”

Jonsson & Alter, 2 (Kontra Musik)

The Swedish producers Henrik Jonsson and Joel Alter have said that they wanted “heavier beats” on their second album, and there’s no doubt that their low end packs a hefty punch. (Unlike their debut, tracked out in jam sessions and mixed down on a laptop, this one was made in a proper studio, with a long-player as the endgame.) But floating on air remains the predominant mode here, with cottony kick drums and airy atmospheres lending the impression of deep house at its most horizontal. Smallville’s night-sky fantasias are the main point of reference for Jonsson and Alter’s twinkling keyboard melodies and general aurora-borealic glow. “En Melodi” traces circles in the air with piano and vibraphone; “Svalor” keeps its drums way back in the mix, shrouded by string pads and a delicate vocal loop. For the most part, the whole album blurs together, and quite agreeably so. Like the best mood music, it never presumes to tell you exactly how to feel; it just soaks into the air around you and amplifies the resonant frequencies of a given mindstate.

Zed Bias, Boss (Swamp 81)

Loefah’s Swamp 81 label swaggers hard. Its titles broadcast brute force — “Mean Streets,” “Sicko Cell,” “Stubborn Phase,” “Don’t Ask, Don’t Get” — and its best tracks inhabit the sweet spot where surly meets slinky. Garage veteran Zed Bias’ Boss certainly fits the Swamp 81 mold. It’s structured around terse, staccato bass, white-hot 808s, and not much else. The opener, “Eingang,” plays with a prancing bass line inspired by early New York house, and the closing “Ooh” nods to Bias’ broken-beat roots, with a lanky, Latin-inspired groove, gooey Rhodes, and soulful vocal shots. But the majority of the record is focused squarely on the club (a point driven home by the fact that the 10-track album is pressed as a quadruple-vinyl package, to maximize audio fidelity). Bias goes light on obvious hooks, preferring the austerity of coolly efficient grooves — the storm-tossed toms and monosyllables of “Tug (Alt Mix),” or the nervous “Think” breaks and jittery son clave patterns of “Ye,” with a queasy phaser effect that rocks it like a seesaw. “Copper” fuses tribal house with dry electro zaps; “We’re There” and “Flamm,” both featuring the Swamp 81 producer Chunky, take 2-step grooves and slow them until they’re muddy and foreboding. The Roy Davis Jr.-assisted “We Are There,” featuring a bright synthesizer lead reminiscent of Mathew Jonson’s sunny meanderings, offers a welcome respite from the darkness. In many ways, the album feels like a companion piece to Special Request’s Soul Music. Bias is less invested in the breakbeat canon, but his perfectionist fine-tuning of rhythms and timbres lends to a similarly claustrophobic atmosphere, as voluminous low-end throb threatens to suck up all the air in the room.