Crouching on an island of rotten linoleum, hammer in hand, Cass McCombs proposes some friendly competition. “If you’re lucky, you’ll get an entire tile to come up at once,” he says as he thumps a putty knife into a seam in the floor. “And whoever gets the most tiles, gets a prize.” It’s a warm September morning, and McCombs, freshly showered in a dirty white t-shirt and blue jeans, has offered to help renovate his friend Albert’s new home, a pre-war row house Albert and his girlfriend Nicky recently purchased on Jefferson Avenue in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood.

In preparation for Nicky’s upcoming birthday party, the three of us are all working separate corners of a small room on the ground floor that Albert will soon expand to house his psychoanalysis practice, once he’s knocked down some walls and sanded away the swamp of glue waiting beneath every tile we remove. The previous owner, a former corrections officer in his sixties, had lived here his entire life. McCombs, as is often the case, is just visiting.

“Oh, oh, I might be getting one here,” Albert says quietly, like he’s got a fish on the line. “Please don’t fuck this up.”

“No,” McCombs groans as he stops to watch him free that first tile. “You guys lucked out. Look at all of this glue over here, just brown all ’round me. I’m stuck in Glueland.”

“You wanna switch?” Albert asks with a laugh as he pulls up another tile.

“Yeah, I do. Either call off the competition or make it fair.”

Albert leaves us to tend to some e-mail and lets the 36-year-old singer-songwriter take over in a less laborious part of the room, a move that turns out for the best. Before long, McCombs has an impressive collection of tiles leaned against the wall. An hour later, the two of us are even at 12 apiece with just two left to uproot. He laughs as a long crack breaks out across the face of my last. “That’s how the linoleum crumbles,” he says, before hoisting a final, pristine tile in triumph.

There was never a prize to be won. But to repay us, Albert treats us to some sandwiches in the backyard, where he and McCombs enjoy a cigarette in the breeze. Over a decade ago, when he first moved to New York, McCombs worked a construction job in Brooklyn and New Jersey: demolition mostly, for a Frenchman named Claude. “I didn’t really intend to move here,” he says. “I was sort of shipwrecked.”

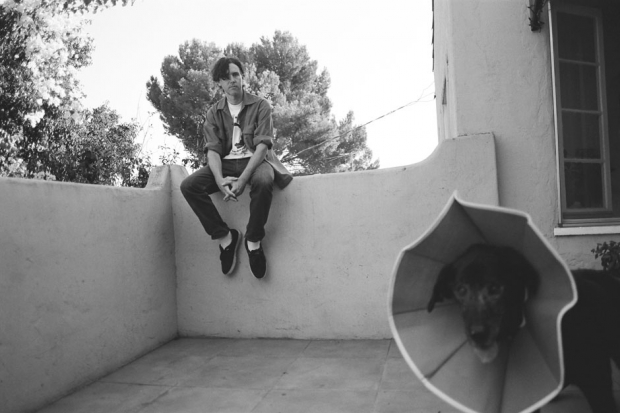

Though he’d originally come to visit family and friends from home in the Bay Area, he stayed a few years, drifting from crash pad to crash pad and job to job, until it was time to move on to another city he’d experience in much the same transitory manner. He stayed with Albert last night, he doesn’t yet know where he’ll sleep tonight, and in less than a week, he’s off to Los Angeles. “I’m totally supported by my friends,” he says. “That’s how I exist.”

The one constant during the past ten years has been McCombs’ inexorable need to write and sing songs. This month, he’ll release Big Wheel and Others, a towering achievement made possible by contributions from those same friends, a deep community of artists, engineers, and musicians he’s met along the way. Only two of the 22 songs across the album’s two discs were recorded by the same combination of players; its vivid, Hieronymus Bosch-like cover art was drawn by none other than Albert, our host and foreman.

“I always think about the band as an allegory for teamwork,” McCombs says to us, a blue New York Mets cap shading his green eyes from the sun. “A baseball team is like a band. Because conceptually, there are no heroes in baseball — there’s just the team. Even the pitcher, who’s supposedly the leader and gets the ‘win,’ statistically, sometimes doesn’t play half of the game.” I ask him if there is one Met in particular to whom he relates. “I like Darryl Strawberry,” he says quickly. “Or maybe Kevin Mitchell — he went on to be a great Giant.” He pauses, holding eye contact for six, maybe seven seconds. “I don’t relate to anyone,” he says. “But Strawberry’s great. That swing of his is just so fluid.”

This is a quintessentially McCombsian exchange: deeply conflicted, strangely enlightened, as rooted in paradox as it is the headlong pursuit of some cosmic truth.

Albert, though, is focused on more mundane matters. “Can you believe how fast we got that done?” he asks in disbelief.

“Exactly!” McCombs shouts. “You’d just be whacking away at those linoleum tiles for days if it wasn’t for us.”

One week earlier, McCombs was passing through Biddeford, Maine, an old mill town just 15 miles southwest of Portland. As part of a three-night, three-date acoustic jaunt through the margins of New England, he and his constantly mutating band were set to play the Oak and the Axe, a café and DIY art space hidden behind a Mexican restaurant downtown. At 8 p.m., that restaurant, Bebe’s Burritos, was filled with dozens of middle-aged, margarita-holding locals getting lost in a grizzled cover band’s similarly grizzled rendition of “Layla.”

Down a harshly lit hallway to the back of the building, past a pregnant doorwoman, there was another world entirely: Arthur Russell‘s cello meditations on the house speakers, a guy in a blazer sipping red wine at his laptop, and a few couples sitting closely in rows of vintage chairs, speaking in hushed tones over plates of homemade crepes from the bar. Beautiful butterscotch tin lined the ceiling; reclaimed wood lined the walls. Pillar candles glowed inside papery birch skins, illuminating an array of dead-flower arrangements in frosted vases. There was a community bookshelf and community artwork and a floor-level stage just large enough to comfortably fit McCombs and two bandmates, who appeared at about 9:45, at which point the room had taken on a dozen more couples and a twenty-something up front in a striped red sweater who’d opted to bring his own dinner from home. The second McCombs opened his mouth to sing, this young man was transfixed.

Standing in the dark, lit only by a shimmering wall of light boxes designed by his friends, Jake and Molly, McCombs casually led the room through an hour-long set of songs old, new, and re-imagined, through bottomless melodic vortexes and obliquely told tales of great existential and emotional despair. “Happy to be in Maine,” he said, shortly after opening with “Buried Alive,” an elegiac beauty from 2011’s Wit’s End, the first of two records he released that year. “I’ve never been to Maine.”

His voice was smooth and clear. During “Big Wheel,” he scatted between verses, parroted the twang of his nylon-string guitar into the microphone, and laughed at himself. Time slowed, as if by design. Everyone in the room looked as though they’d taken a shot to the stomach or head. But my neighbor in the sweater — his mouth always parted and eyes always wide — was feeling this all in another way, which is to say, ecstatically: gasping audibly during choruses, slapping his knee in disbelief as each song came to a close.

Afterwards, as the room emptied itself and the band dispersed, the two shook hands just before McCombs disappeared out the front door. I listened to the guy for a moment as he spoke to a fellow audience member, a bespectacled man in a white button-down shirt and chinos who was also lingering a while longer. “I don’t know, man,” he said, visibly stunned. “He was busting out some notes I’ve never heard before.”

McCombs offers little in the way of details about his past or personal life. “It’s a decision I made a long time ago,” he says of the former. “Leave it behind.” Born in Northern California in 1977, he grew up among step-siblings and half-siblings, with “lots of different religious experiences: Baha’i, Unitarianism, Catholicism, atheism, and rock’n’roll.” He played piano and saxophone, danced and drew, sang in choir and acted on the stage. There was always a guitar in the house, and he would always try to pick it up. “But it didn’t fit my little hands until I got a little bigger,” he says. “I grew into the guitar.” As a teenager, he started performing in cafés and playing in bands with friends equally enamored by the varying psychedelic properties of Metallica, Guns N’ Roses, and Primus. “I was an acid kid,” he says. “Anything that remotely suggested acid, I was there.”

After he graduated from high school (“barely,” he says), McCombs left for New York City, where he eventually lived and began playing with members of Gang Gang Dance, White Magic, and Animal Collective, all vital components of a downtown community whose experiments found a home at Tonic, a now-defunct venue on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. A few days after we worked on Albert’s house, McCombs and I meet at B&H, a Kosher diner not far from both Tonic and the café where he played his first show in New York: the Pink Pony, also gone.

When I walk in, he’s seated at the countertop with his nose in a small notebook, nodding and singing to himself. He’s just finished up a bowl of hot borscht in an effort to keep Kosher. (“Oh, you gotta: That tradition has lasted this long, you know what I’m saying?”) He also means to maintain his diet of warm foods and liquids, as prescribed by a “witch doctor,” an expert in traditional Chinese medicine he’s been visiting of late.

That sort of personal idiosyncrasy is McCombs’ default mode of being. He is, in a variety of conversational situations, quick to cite stories from the Bible. He has designed board games and fonts. His voice, he argues, is not really his, but rather, the sound of the muse, of the collective unconscious, a notion that, by its very nature, calls into question the necessity of inquiries that tend to come up in interviews, which he mostly avoids. “There are a lot of heathens out there,” he says, “that don’t realize that music comes from the Great Spirit. To refine it and to trace it to the individual is blasphemous. An artist is a butcher, and it’s fine to give respect to the meat man who brings in the goods, but it just feels limited.”

Spiritually, musically, he is nothing if not omnivorous. “I was just a folk singer,” he says of the late ’90s and early ’00s in New York. “I cut my teeth on the streets, you know. I don’t see that too much anymore. I don’t think it occurs to people that they need to pay their dues on the sidewalk. You just bring your guitar, and you try to sing for your supper. I was inspired by hunger. A lot of people don’t know what it’s like to actually be hungry. I do. I’ve also slept on the streets.”

In 2003, he left New York for Baltimore, where for a hundred dollars a month he lived in an abandoned supermarket that doubled as a rehearsal and studio space he shared with punk bands like OXES and Lungfish. He released his debut that year, A, a spare but hypnotic record that would launch what has become one of the past decade’s most compelling bodies of a work, a catalog whose obvious musical touchstones — Robert Smith and Buddy Holly, John Lennon and Lou Reed, Hank Williams and Leonard Cohen — aren’t nearly as important to the songs as the company kept by their creator. In L.A., he befriended legendary lo-fi figurehead Ariel Pink as well as Ariel Rechtshaid, a producer and songwriter who has worked most recently with Justin Bieber, Major Lazer, and Vampire Weekend. While in Chicago, McCombs crashed a couple of blocks away from Rosa’s, a blues lounge where he’d take in shows by the likes of Pinetop Perkins and the late Honeyboy Edwards, with whom he also played.

In the process, McCombs has quietly become something of a songwriter’s songwriter, developing a following Vampire Weekend multi-instrumentalist Rostam Batmanglij calls the “Cult of Cass.” “He’s pretty unafraid of simplicity,” says Batmanglij, a devotee of McCombs’ understated 2007 LP, Dropping the Writ. “That’s what draws you in. But the reason why you want to keep listening to his songs over and over again is that there’s something there, emotionally, that haunts you. And when you get down to that, it’s actually never so simple.”

If he’s troubled, McCombs says, he gets it out. “It’s like eating,” he says of writing. “The songs are just how I’m feeling in that hotel room, in my friend’s house. Sometimes I feel like I finish a song, and there’s another song that I have to write in response to that song. Each is like its own separate feeling, its own separate universe. Just that, nothing more.” When asked what troubles him, McCombs proffers a list: “Constipation. Repression. Racism. Sexism. Prejudice. Violence is troubling.”

Rechsthaid, a fan of McCombs’ since 2005’s PREfection and frequent co-producer since 2009’s Catacombs, considers him to be the finest songwriter of his generation. “Sometimes I hear one of his songs and it’s hard for me to believe that he wrote it,” Rechtshaid says. “It’s hard for me to believe that it hasn’t been around forever, that it’s not an institution. He’s always been admired by huge artists, been invited to go on big tours, and he rejects the things that don’t make sense because he knows better than to try and fit into something that he doesn’t fit into. Some people may see that as self-sabotage. I disagree.”

“An American poet,” McCombs says, reading aloud from a passerby’s Jim Morrison t-shirt in Tompkins Square Park. After an egg cream and some coffee, we’ve taken a seat beneath the Hare Krishna Tree, an enormous elm that has been a place of communion and site of worship for Hare Krishnas since the late ’60s. Two months earlier, McCombs says, he performed a play in this very spot, written by a friend of his. “We had two dancers and a speaker,” he recalls, slipping off his black skate shoes and stretching his toes. “It was about recycling.”

On a philosophical level, performance has become paramount to McCombs in recent years, especially as the way he’s looked at his own work has changed. “I don’t want that to go away, the ability to play constantly,” he says. “That’s an incredible privilege. The records? Whatever. I could not put out records. But the ability to be invited to play shows all year — I want to maintain that, because playing a show really demonstrates the being in the here and now. Each second counts. We all enjoy the feeling of the moment and just watch it pass. You open up the wormhole to let in spirits and beings, to get to the magic. You pound on the wall until it starts to crack, to break on through to the other side, you know what I’m saying?” He pauses to watch a pigeon pecking at garbage near our feet. “There is no future. I don’t plan ahead.”

Which wouldn’t be a particularly effective way of drumming up excitement for a new double album, had Big Wheel not benefitted a great deal from that kind of laissez-faire thinking. In August of last year, McCombs was invited to attend Move Me Brightly, a five-hour jam at Tamalpais Research Institute in San Rafael, California, in celebration of what would have been Jerry Garcia’s 70th birthday. Along with several other musicians, many of them unfamiliar to one another, McCombs sang and played guitar on seven Grateful Dead songs, including “Dupree’s Diamond Blues” and “Terrapin Station.” He caught the attention of Mike Gordon, a bassist whose band, Phish, McCombs had long enjoyed.

“Playing with him, watching him, listening to him, you realize he’s a bridge,” Gordon says of McCombs. “Imagine him at this Grateful Dead gig. How does this guy appreciate the Grateful Dead? But it all makes sense: It comes down to a mood. His songs have this flow, where they just keep going and going, like a biplane over rolling hills, continuing and continuing to the point where they become meditations. In that way, it is like a Grateful Dead jam. Even though he’s a singer-songwriter, he still embraces what happens when you just go.”

Gordon and McCombs began exchanging e-mails, and not two months later, as the latter returned to Brooklyn with a wealth of material and studio time booked, he established one rule: The door to the studio stays open, so anyone can and should come through and play. Gordon contributed bass to nearly half the record. The late actress and singer Karen Black — with whom McCombs had collaborated on Catacombs, and for whom he’d specifically been writing another album— gave what would become her final vocal performance on “Brighter,” before losing her battle to cancer in August of this year. Former Girls bassist Chet “JR” White mixed the record and contributed “paper tearing.”

Big Wheel‘s list of contributors is long, and the result, captured live with very few overdubs, nearly became a triple album. “We were trying to push it as far as we could take it,” says McCombs. “But I have very simple goals: I want to learn more. Even when I was young, I was very serious. I’ve always despised twits. I’ve always wanted to learn from older people, keep my eyes open. And in getting older, I’m no longer afraid to regard my music as labor. Before it was, ‘No, this is just for fun and it doesn’t matter. If I make a mistake, no one is paying attention.’ But I’ve set a higher code for myself.”

On the face of things, McCombs’ feelings about this record — and his recorded work in sum — provide a slippery parallel to his intense discomfort not just with the idea of settling down, but with subjecting his life and music to the rigid confines of a written narrative. “Remember when you were a kid, and you thought Michael Jackson was saying something, and you find out later that he was saying something different?” he asks. “You weren’t wrong to think that: A song lives in an interpretative realm, and it doesn’t exist in any one place. A recording exists on wax, forever. That’s why I hate recording. I’m not comfortable with the permanent record. There’s nothing permanent about this world, least of all fuckin’ rock’n’roll records.”

But couldn’t each of these records be considered a document of where you were, emotionally or otherwise, at a given moment?

“To me, the records aren’t a document. They aren’t. The song is a fleeting experience, just like every other experience in life. It’s no different than anything else, no better, no worse. Maybe there’ll be some virus that will wipe out all recorded material. Maybe wax will melt, and the new aeon will come. Maybe there will be no corporal plane in the Age of Aquarius.”

Maybe, I say. But maybe you’ll change your mind.

“We all have changed our minds so many times,” he says. “I might change my mind about everything I’ve told you in the last few days.”

You probably will, I say.

“I probably will. And that’s life.”

On behalf of Albert, McCombs has asked me to come back to the house that night for Nicky’s birthday party. When I arrive, a little after midnight, most of the party is downstairs on the garden floor, dancing under blue light. Albert’s doing a drunken twist, Nicky’s following suit, and the house is full of familiar faces, singer-songwriters like Mike Wexler and Sleepy Doug Shaw, a Big Wheel contributor, included. Tiki torches are aflame outside, two women are discussing Qigong in the kitchen, and McCombs, true to form, is long gone. Albert says he left hours ago.

Two weeks later, McCombs and I speak on the telephone. He was in L.A. and had just performed two of his songs at Karen Black’s memorial service. I asked him how he was feeling ahead of the album’s release. “I don’t have any wild illusions for what may come,” he told me. “I think that when you’re young, you have an improvisational ambition. You don’t know what to expect, but you want the world. It’s like a mixture of lust and greed, with no basis in reality. I might still be lusty, but my ass is planted.”

I asked him about the party, and if he’d had fun. He muttered a bit, demurred.

But you were among friends, I say.

“Yeah,” he replies. “I don’t know. I’m not a party animal. I’m definitely not the belle of the ball. I’m the black sheep.” He grew quiet. “But we did put some new life in that old house.”