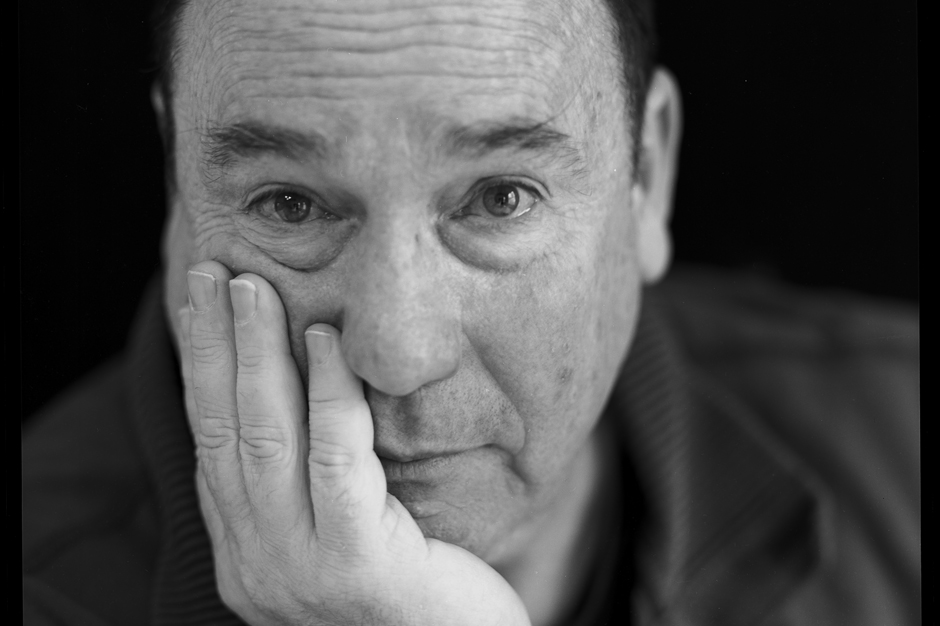

Percussionist William Winant has been the avant-elite’s go-to percussionist for more than 35 years. The list of folks he’s worked with is basically an abridged history of the 20th century’s back end: John Cage, Iannis Xenakis, Pierre Boulez, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Frank Zappa, Alvin Lucier, Anthony Braxton, John Zorn, Sonic Youth, and Mr. Bungle, to pick a handful. But despite appearances on more than 200 recordings, he had never released a proper solo album, a grievous wrong long-running indie label Poon Village has finally righted with the release of Five American Percussion Pieces.

A vinyl-only compendium of Winant’s disciplined precision, the result doubles as a hypnotic overview of underchampioned percussion compositions, banging and clanging through works by Lou Harrison, Michael Byron, and Alvin Currran. Using Winant reimaginings that date back as far as 1976, it veers from hypnotic snowflakes of vibraphones to cartoonish cowbell gamelans plonking and plunking. But the highlight is the brand new version of James Tenney’s 1971 piece “Having Never Written a Note for Percussion,” a meditative slow-burner that’s basically a Richard Serra sculpture performed on a single tam-tam.

Stream the album in full below; for further explication, Winant stopped by the SPIN office to chat about Iannis Xenakis and “Blurred Lines.”

William Winant, Five American Percussion Pieces

:audio=0:117985:playlist:William Winant, Five Percussion Pieces :

What took you so long to do a solo record?

It would take me probably two or three months to learn these pieces and then record it, so it always seemed like more trouble than it was worth. Then Kristin [Anderson of Poon Village] came and said, “I don’t care! Send me anything!”… I didn’t have to go into the studio, spend a lot of time practicing pieces — the record goes all the way back to 1976, when I was a student at York University. I think one of the things is off an audition tape that I sent to get into a masters program at Mills College. They were on cassette tapes.

The James Tenney piece is the only new recording. Can you explain it?

The James Tenney piece was part of a series of pieces that he called “koans.” These “postcard pieces” were pieces he would write for friends on a postcard and then mail them to his friends. This piece, “Having Never Written a Note for Percussion,” was written for my teacher, John Bergamo, and then actually the score is a postcard. Basically it’s just a crescendo and decrescendo, with a roll notation in the middle of it. So it starts from very, very soft to as loud as you can get to very, very soft, and the only other instruction is “for a very long time.” It can be played on any instrument. I chose to play it on a giant tam tam, or large gong.

What does it feel like to play that piece?

For me it’s like a form of meditation. You kind of get into it, you zone out. You relax into it. I kind of feel exhilarated after I play it. Every tam tam that I do it on is different. There is an endurance thing in it. Obviously when I was younger I was able to do that piece for 20 minutes or 18 minutes, and now most of the versions I do are around 10 or 12.

What are you playing in “Bang Zoom”?

Those are 13 tuned cowbells from Germany. And the real name for them is almglocken. They’re just these bells they put on cows, [so] that the farmers in the Alps would be able to find their cows. We got these 13 cowbells and them made a rack for them so I can play them standing up.

“Song of Quetzalcoatl” is a piece for four percussionists. Did you do all the parts yourself?

That piece is done with the William Winant Percussion Group. I’ve recorded, with that group, pretty much all of Lou Harrison’s percussion ensemble music and percussion music. Lou is a very important percussion composer, one of the first along with John Cage and Edgard Varese to write exclusively for large percussion groups. I was one of his heirs. When he died, he willed me his collection of percussion instruments. These recordings — both “Song of Quetzalcoatl” and the solo piece — were done under Lou’s supervision, using Lou’s instruments.

The second volume of this series has a Xenakis piece. You got to work with him around 1983. What about him would surprise us?

He was kind of the “old-school master musician.” It was, for me, hard to get close to him. But as I did these concerts, and he heard me play, he kind of warmed up. He has a very strong vision of what he wants. Once you got over this initial hump of meeting him and working with him, he seemed wonderful. When he was in the Bay Area, he liked to drive around and look at the architecture and look at the different buildings. I think he studied architecture before he even became a composer.

When you were on the last Mr. Bungle tour, did you know that was gonna be the end?

No. In the beginning, it seemed like this would go on for a while, but then I as I started to tour with them a lot, I could see the cracks coming. Definitely, the last European tour, I could see this was gonna be the last for a while. But, you know, at this point, all of these people are working back together. I just did a record with Trey [Spruance] and with Mike [Patton], for Secret Chiefs. They did a version of a Scott Walker song called “Ballad of Jackie.” It’s actually a Jacques Brel song. Trey asked Patton if he would sing the track, and Patton sang on it, and he sings in French and in English. So, in a way, they’re starting to work together. It seems that, as time passes, and people are getting mature, then maybe down the road something might happen. You never know.

This record is very abstract. What do you listen to for comfort food?

Right now I’ve been listening a lot to the new Smile, Brian Wilson. The new reissue of all the old stuff from the ’60s. I would say I’ve listened to hours and hours upon hours of that stuff.

What do you think of the drum sounds of contemporary rap and electronic music?

I like those electronic drums in that Miami Vice — boo-doo-doo-doo-doo, doo-doo-dooo.

What about the drums on “Blurred Lines”?

The one that’s the big summer hit? It’s great. I like that stuff. I think the way these people come up with these drums beats and these sounds? I really like it.