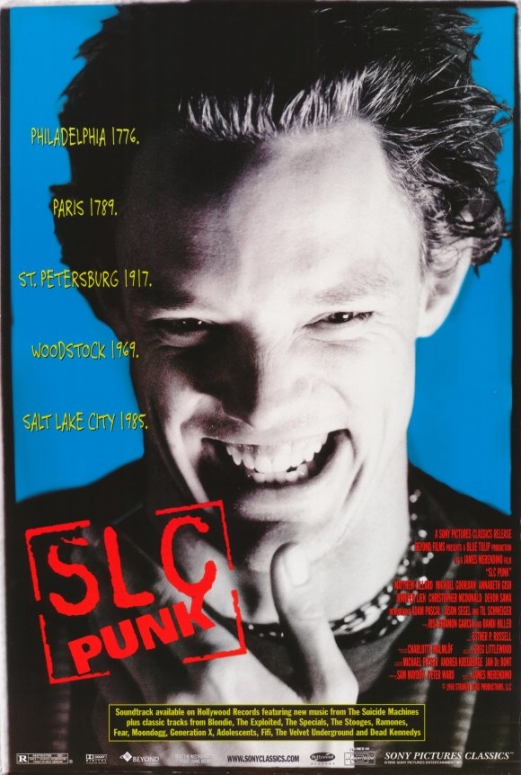

At the end of writer-director James Merendino’s 1998 screed of a film, SLC Punk!, the main malcontent, Stevo, played by Matthew Lillard, sits on a Salt Lake City bench wearing a suit and tie, his short hair neatly groomed. Looking directly into the camera, his eyebrows arching almost imperceptibly, Stevo, who until this point had sported tattered clothes and a Mohawk, declares: “When all was said and done, I was nothing more than a goddamned, trendy-ass poser.”

It’s a tough ending to a scabby movie, and it makes you question the freewheeling and furious 98 minutes that came before. Did Stevo give up on his anarchic philosophy too easily? Is he joking about going straight? Set in 1985, SLC Punk! bursts with Stevo and doomed sidekick Heroin Bob’s harangues about how to live out loud in a quiet, closed-in city. Fifteen years after its premiere — and 15 years, less a month or two, after it disappeared from theaters — the movie still finds new minds to infect with its provocations.

“I walk with the movie like a badge on me every day,” says Lillard, 43, who has since carved out a successful career as a character actor. “If I walk down the street and ten people recognize me, nine of them will be disenfranchised punk-rock kids. When I was growing up, The Decline of Western Civilization was the VHS tape passed around high school. The same thing started to happen with SLC: Punk!”

Michael Goorjian, who played the Travis Bickle-inspired Heroin Bob, also isn’t immune to the film’s influence. “There are a bunch of people running around with Heroin Bob tattoos,” he says with a laugh. “It’s a little scary.”

That this movie, filmed fast and cheap during a Salt Lake City winter, moshed its way into cult acclaim is especially gratifying for Merendino, who based much of the screenplay on his own experience growing up as an anarchist punk in the titular straitlaced town.

“The whole reason I wanted to make the movie,” says Merendino, “was to help people understand what, exactly, being a punk is about. Previous to that, I kept seeing punks in movies shown as guys with knives mugging people. All my punk friends were intellectuals. I wanted to show there was some complexity to the lifestyle.”

To the film’s credit, complexity isn’t the thing that initially registers as you watch Stevo and Heroin Bob tussle with rednecks, philosophize in head shops, and generally try to find a way not to feel like a phony or a victim in a world that seems set up to force its protagonists into either of those two roles. Set to a soundtrack that rages with the Stooges, Minor Threat, Dead Kennedys, and the Ramones — plus a pivotal aural flashback to Rush — and filmed in a frenetic, kinetic style, SLC Punk! is a visceral blast. The images and action and ideas — delivered via Lillard’s rants — are pure punk energy.

“I remember James and his DP setting up these crazy shots with a bunch of cameras,” says Annabeth Gish, who played Trish, the muse-ish object of Heroin Bob’s affection. “I’d worked with Oliver Stone and Lawrence Kasdan, and what we were doing [on SLC Punk!] felt radical. I definitely had the feeling of ‘Wow, this is some cool-ass filmmaking.'”

And while the film’s technical exuberance makes the strongest impression, it’s the attitude that’s had the longest-lasting effect. Take Stevo’s monologue to his fomer hippie parents (dad is played by the great Christopher McDonald):

You two are divorced. So love failed. Two: Mom, you’re a New Ager, clinging to every scrap of Eastern religion that may justify why the above said love failed. Three: Dad, you’re a slick, corporate, preppy-ass lawyer. I don’t really have to say anything else about you, do I, dad? Four: You move from New York City, the Mecca and hub of the cultural world, to Utah! Nowhere! To change nothing! More to perpetuate this cycle of greed, fascism, and triviality. Your movement of the people, by and for the people, got you… nothing! You just hide behind some lost sense of drugs, sex, and rock’n’roll. Oooooh, Kumbaya! I am the future! I am the future of this great nation which you, father, so arrogantly saved this world for. Look, I have my own agenda. Harvard, out. University of Utah, in. I’m gonna get a 4.0 in damage. I love you guys! Don’t get me wrong, it’s all about this. But for the first time in my life, I’m 18 and I can say, “FUUUUUCK YOU!”

These are hardly original ideas. But for a certain type of teenager, hearing someone else articulate them on screen — particularly if that someone has a massive blue Mohawk — can have the force of someone hearing the Clash or the Minutemen for the first time.

“Because of the rants and digressions,” muses Merendino. “The movie seems to assert that it knows something. If you’re 16 years old, and you’re living in a small town and don’t really fit in or don’t know how to channel your feelings, suddenly you can see this movie that says, This is how to do it. It’s easy to understand how that can turn into a cult thing.”

Lillard points out that, even today, the film is still a beacon: “The things you hear in the movie aren’t exactly what you hear in The Avengers. Contrary to what people might think, there are a lot of kids out there who could still use validation and justification that it’s okay to be punk rock.”

So how, then, to explain the ending’s seeming capitulation? “I think it’s appropriate to the film,” argues Goorjian. “It’s maybe not a fun ending in a stereotypical movie sense, but it does point out the fucked-up situation of being a punk: are you actually one or are you just playing the role? There’s not necessarily an answer to that question.”

Merendino adds that the final scene represents “the contrarianism of punk again. When [Stevo] says that he’s selling out, it’s sarcastic. I wanted to leave it ambiguous, but I probably could’ve done a better job of underlining the sarcasm a bit more.”

He’s hoping to get a chance to put a finer point on the film’s ethos — Merendino recently finished a script for a sequel in which he’d catch up with the main characters 18 years after the first film left off.

“They’re all having their midlife crisis,” explains Merendino about the sequel’s narrative. “They’re paying taxes, they’re having jobs, they’re doing things that aren’t very punk but they didn’t give up what they believe in.”

Though the script is finished, it’ll still be a while before we see Stevo and Co. back on screen. “I’m trying to put together the money, which is maybe not the most punk rock thing to say,” says Merendino wryly.

He remains hopeful, though, that the second time around, “People will still have strong feelings about the ending.”

Stevo wouldn’t have it any other way.