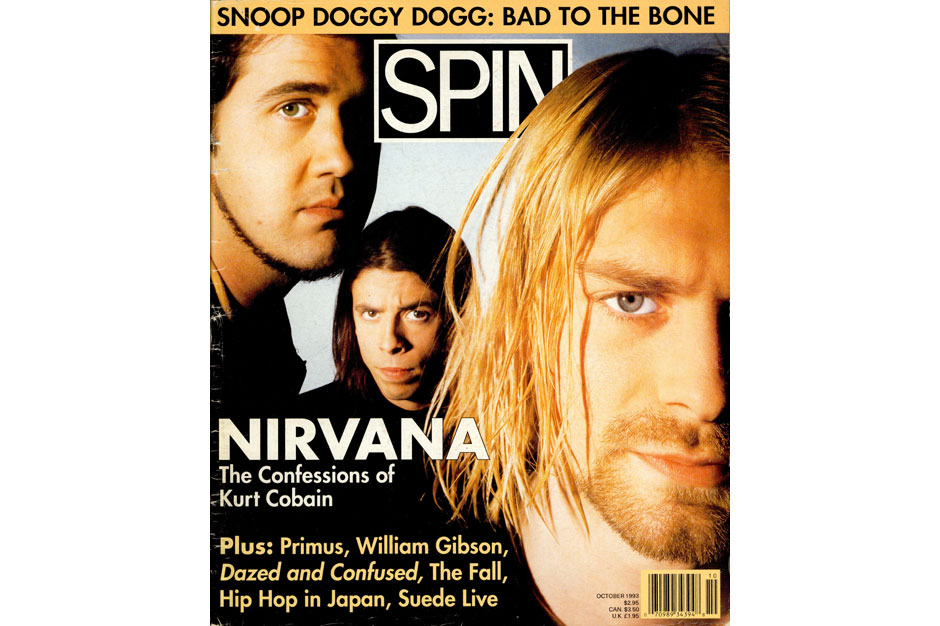

[This story was originally published in the October 1993 issue of SPIN. In honor of SPIN’s 30th anniversary, we’re repromoting this piece as part of our ongoing “30 Years, 30 Stories” series.]

Fame has a vaporizing effect. It lifts and floats the celebrity into our most private venue: dreams. But for Kurt Cobain, our collective obsession seems like a car’s stark headlights, freezing its unassuming victim in the glare. “In my dreams, there’s always this apocalyptic war going on between the right and the left wing,” he says, sitting on the plush burgundy couch in his Seattle living room. “The last dream I had like this was two nights ago. Courtney and I were in the Hollywood Hills, and Arnold Schwarzenegger was my neighbor. I was completely disgusted by the idea of living next to these people.” Cobain speaks in a lilting Pacific-Northwestern drawl, like a grungy Quentin Crisp. “So I went down to where the oppressed people were starving on the streets, killing each other for a quarter. In one part of the dream I was being honored for something and the ceremony was at an S/M club, but it was a really nice one. It didn’t have chains on the walls, just beautiful flowers. Lots of stars went there.” Cobain glances up at the small plastic doll in a nun’s outfit propped up on the mantel, one of the hundreds of dolls that he and his wife, Courtney Love, leader of the band Hole, have collected. “I had to make an entrance from the top of the stairs, and because of the way people think of Courtney, she happened to be this two-foot-tall black midget with huge feet. She waddled like this…” Cobain sways back and forth like Charlie Chaplin. “As soon as she made her appearance someone kicked her down the stairs. I just started screaming.”

As it would with anyone, the past 18 months have taken a fierce toll on Nirvana and the Cobains. They’ve struggled coming to terms with their gargantuan stardom, straining to get their footing on the unfamiliar and sometimes brutal landscape of fame. The terrain has been dotted with obstacles: some mere potholes, some treacherous landmines. With the follow-up to Nevermind, In Utero, due on September 14, the Seattle-based trio hopes to trade in its celebrity status for the more comfortable role of rock band. But erasing the lunacy of the months gone by may require more than a bracing blast of punk rock.

Last September, Vanity Fair ran a much-publicized piece on Love. The article quoted her as saying, among other things, that she used heroin while pregnant with their now one-year-old (and healthy) daughter, Frances Bean, which she later denied. Cobain refers to Condé Nast, which publishes the magazine, as “a bunch of right-wing, high-fashion, Christian Satanists. They have the power to eliminate anything that threatens them.”

Cobain tends to go to extremes when discussing the abuse he’s taken from the mainstream media. His outrage borders on a persecution complex, but the press has left him feeling terminally unprotected, his day-to-day life and love compromised in ways he never imagined. He’s horrified about rumors that have been circulating concerning a recent trip to New York City, where he and Love were supposedly so high they were puking in the back of a cab, and when they got out they left little Frances Bean behind in the backseat. The story continues with the cabby driving around for hours not knowing there was a baby in the car.

“It’s like the Rod Stewart semen story,” I tell him. “You’re a part of modern folklore.”

“Geez,” Cobain says. “I could live with that, Kurt Loder saying, ‘There was a half gallon of semen found in Kurt Cobain’s stomach.’ That at least is funny.”

Notoriety doesn’t really bother bassist Krist Novoselic. He says he makes himself available so often he’s gotten over any phobia, but he admits to awkwardness when meeting people. “If you introduce yourself they say, ‘I know who you are.’ And if you don’t they think you’re arrogant.”

Dave Grohl, Nirvana’s drummer, figures the reason he’s seldom recognized is because people can’t really see him behind his drums and his long hair. Though he’s never been stopped on the street, something he recently heard did freak him out. “There’s a guy in New York City that goes into this record store every single Sunday and claims he’s my father. It’s creepy.”

Both agree that while stardom is sometimes hard for them, it’s hell for Cobain. “It’s a load of s**t on Kurt’s mind that he doesn’t deserve,” Grohl says. “You can tell when he’s upset, and it ends up bothering all of us.”

“You know how Tabitha Soren’s delivery is usually kind of flat and calm? I’ve noticed whenever she reports anything on us, she really gets into it — her eyebrows raise, and she gets this venom in her voice.” Cobain says this as we settle into a booth with Novoselic at the Dog House Restaurant, a diner in Seattle that’s been open since 1934. A sign above the counter says all roads lead to the dog house. Cobain’s intensity is startling, practically electric, like the hum from overhead power lines. A bad case of scoliosis as a child has left him permanently hunched, and in his plaid hunter’s cap, flaps down over his ears, and visor pulled low for privacy, his ice-blue eyes are transfixing. His black tennis shoes have “Fugazi” written on the toes in black magic marker, each foot with a different spelling. He lights yet another cigarette, his fingernails a splatter of chipped red nail polish.

Cobain is referring to a July 12 MTV news segment based on a piece in the Seattle Times. The article reported a domestic disturbance at the Cobain home, claiming the couple were physically fighting over their possession of several handguns and an AR-15 rifle.

Cobain shakes his head. “I was just so surprised to find the police report so detailed, yet so completely wrong.” He sinks deeper into the booth. “What really happened was that Courtney and I were running around the house screaming and wrestling — it was a bit Sid and Nancy-esque, I have to admit — but we were having a good time. And then we get this knock on the door, and there are five cop cars outside, and the cops all have their guns drawn.” His voice mirrors the absurdity of the situation. “We were in our pajamas. I was wearing this long black velvet pipe-smoker’s jacket. Not the most desirable thing to be arrested in…” The police explained a new Washington State law that requires that someone be arrested in cases of domestic violence. “That’s when we did start arguing, about who was going to jail. I said, ‘I’m going,’ and Courtney said, ‘No I’m going.’ And I said ‘Noooo, I’m the man of the house. They always arrest the man.'” Cobain smiles. “I kind of regret that now, because the idea of Courtney as a husband-beater is kind of amusing,” he says wryly. “She did throw juice at me and I did push her, but it was about who was going to jail.”

Novoselic, tall and Abe Lincoln-like, listens sympathetically. “Just as we were going out the door,” Cobain continues, “the police said, ‘By the way, do you have any firearms in the house?’ And I said no, because I didn’t want this to turn into an even bigger deal. But Courtney said yes.” Cobain’s cheeks flush, his narrow shoulders tense. “I’m in full support of that law though. I’ve witnessed that kind of domestic violence. On one occasion my mom’s boyfriend was beating up on her. He’d done it before, but I only witnessed it once. He was this huge Yugoslavian macho man who drank a lot of booze. She had two black eyes and had to go to the hospital.” Cobain’s own eyes grow as big as saucers, as it becomes painfully clear why this accusation has affected him so deeply. “I am sympathetic to this new law,” he says quietly.

Novoselic has a calming effect on Cobain, bolstering him verbally, talking him down when he grows too paranoid. He tells how the Seattle Times called his mother for her comments regarding the Cobain-Love allegations. Mrs. Novoselic refused to say anything; Novoselic has trained her not to talk to the press, promising to “give her a new roof on her house” if she kept quiet.

Grohl, on the other hand, deals with the treadmill of catastrophes by staying out of the loop. “I love to play music with Chris and Kurt, but I don’t like all the hubbub that surrounds it,” he says. “Some people have to have psychodrama, but I have to not have it.”

This current rock’n’roll juggernaut is a long way from the band’s humble beginnings. Cobain’s early years were spent in a trailer park in Aberdeen, 100 miles south of Seattle. Novoselic grew up in Los Angeles before moving to Aberdeen at age 14, where his mother still runs Maria’s Hair Design.

In high school Cobain won a scholarship to art school, but he chose not to attend. He was more interested in music, specifically in local sludge-rock heroes the Melvins. Cobain incessantly watched the band rehearse, and eventually wrote and recorded songs with the Melvins’ drummer, Dale Crover. Novoselic, also a Melvins insider, was impressed by the tape, and in early 1987, he asked Cobain if he would like to start a band together. After forming this early incarnation, both left Aberdeen: Novoselic moved to Tacoma, finding work as a house painter, while Cobain settled nearby in Olympia, a place he’d always thought of as a “cultural Mecca,” eventually working as a janitor in a dentist’s office.

They gigged in the area, and soon after booked recording time at Reciprocal Recording with producer Jack Endino. There they recorded a demo tape, which Endino passed along to Sub Pop’s Bruce Pavitt, who was duly impressed. “Love Buzz/Big Cheese,” the band’s first single, was released in October 1988, followed by 1989’s Bleach, their debut LP, which they recorded in only three days for a mere $600. It wasn’t until 1990, after going through a handful of drummers, that Cobain and Novoselic drafted Grohl, whom they spotted at a gig behind the kit for the D.C. hardcore band Scream.

As a result of their fans having a difficult time finding their records, and their label, Sub Pop, prowling for a distribution deal, Nirvana began entertaining the idea of jumping to a major label. The band shopped the songs that would end up on Nevermind, recorded by a Madison, Wisconsin, studio owner named Butch Vig. A subsequent bidding war broke out culminating in Geffen buying out its Sub Pop contract and offering the band a reported $287,000 spread over two records. Vig eventually produced Nevermind, with Andy Wallace handling the final mixes. Nevermind, which record executives expected would sell around 300,000 copies, flew out of stores at a breakneck pace. MTV endlessly aired the video for “Smells Like Teen Spirit” (later even saturating America with its parodic partner, “Weird Al” Yankovic’s “Smells Like Nirvana”). The single went straight to the top of the charts, and Nevermind went on to sell five million copies in four months (it has now exceeded nine million worldwide). The record’s unparalleled success has altered the course of music, fashion, the recording industry, and deodorants. Nirvana went from being just another punk band schlepping around from gig to gig in its van to the punk band. Nirvana’s sound helped create and define a category of music. Nevermind also made the band members Rock Stars.

“I really miss being able to blend in with people,” Cobain says wearily. “It’s just been lately that I could even handle being recognized.”

Cobain tells me about an incident that took place when he went to see a Melvins show in Orange County, California. “One by one, these drunk, sarcastic twentysomething kids would come up to me and say, ‘Aren’t you in the B-52’s?’ Just trying to start a fight. One guy came up, smacked me on the back, and said, ‘Hey, man, you got a good thing going, just get rid of your pissy attitude. Get off the drugs and just f**king go for it man.'”

There are times when Cobain yearns to take his fans aside, explain the endless complications, pressures, and compromises of stardom, prove to them that in his heart he’s still the same lonely Aberdeen kid whose life was irrevocably bettered by punk rock. Once in a while he doesn’t have to. “There were these, like, ten-year-old kids at a Butthole Surfers concert. They had green hair, they were skater punks who had made their own T-shirts with their favorite bands written on them. I could tell we had some kind of impact on them, and so had punk rock, because they didn’t want autographs. They just wanted to shake our hands and say thanks. I get a thrill meeting kids who are into alternative music. To be that advanced at that age makes me so envious.”

Cobain is clearly pleased that he’s helped nurture a subculture, one that was much less accessible when he was their age. Still, with Nirvana’s new record, In Utero, about to be released, it’s impossible not to wax nostalgic about life pre-Nevermind, pre-grunge.

“It was just so much simpler then,” Cobain says. “I was just getting out of this heavy period of depression… I lived in bed for weeks, reading Beckett, writing in my journal. Dave and I were living in a tiny apartment, eating corn dogs and potatoes. The place was a mess, cigarette butts everywhere, half-eaten food. Chris and I pawned all our equipment. Once I even had to go to the hospital, get hooked up to an IV because of dehydration… but as soon as we got to L.A. to record Nevermind, all that lifted. It was totally warm and kind of tropical. We stayed in the Oakwood Apartments, most of which were filled with Star Search mothers and kids. Kind of gross, but it was such a relief. They had a weight room and I cooked fish dinners.” He pauses and sighs. “This time, with In Utero, it seems like it’s taking forever. I feel like I’m stuck in a void.”

At around 4:30 in the morning, Geffen publicist Luke Wood volunteers to drive me from Cobain’s house back to my hotel. Cobain, whose 1990 Volvo has come up lame, says he wants a ride to a friend’s house. Wood asks if he wants to call his friend, make sure he’s awake. Cobain shakes his head no. We drive down Interstate 5. The few lights left in the hills surrounding Seattle make the water glitter — the place has a dreamy feel, like Oz. We pull off the highway, then, following Cobain’s instructions, zigzag from one side street to another. It’s an older neighborhood, three-story wood houses nestled side by side. “This is it,” Cobain says. “I’ll get off here.” He opens the door. It’s drizzling. All the houses are dark, quiet. I say good-bye, leaving him standing on the wet pavement, lit by a lone street light, preoccupied and exhausted.

The ghostly spectre of Cobain, adrift in suburbia, with dawn still an hour away, is mirrored by his uncertainty over In Utero. “I haven’t heard enough positive feedback. The initial tapes from the studio don’t give me the same chill. With Nevermind, we were so musically validated it was almost embarrassing, but with this record because of the production [infamously recorded by Steve Albini], the songs, and the way we approached the record, you really have to listen a few times to be able to understand it.”

Cobain, though hesitant, is genuinely proud of In Utero. “The lyrics on the new record are more focused, they’re almost built on themes,” he says. “With Bleach, I didn’t give a flying f–k what the lyrics were about. Eighty percent were written the night before recording. It was like ‘I’m pissed off. Don’t know what about. Let’s just scream negative lyrics, and as long as they’re not sexist and don’t get too embarrassing it’ll be okay.’ I don’t hold any of those lyrics dear to me. Nevermind was an accumulation of two years of poetry. I picked out good lines, cut up things. I’m always skipping back and forth to different themes. A lot of bands are expected to write as a whole. One song is supposed to be as cut-and-dried as a Dragnet episode.”

The songs on In Utero are indeed more concentrated lyrically. “Scentless Apprentice,” co-written by all three members of Nirvana (a process Cobain refers to as “a breakthrough in our songwriting”) is based on Cobain’s favorite novel, Patrick Suskind’s Perfume. Perfume’s main character is Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, a strange, odorless monster of a man with an acute sense of smell who works as an apprentice to a perfumer, and in his spare time kills virgins in order to steal their scent. The song’s lyrics paraphrase from the book (“Most babies smell like butter,” goes one line), as Cobain brutally connects his own discomfort with the world to Grenouille’s horrific deeds (“Go away, get away, get away,” Cobain begs). Besides, both Cobain and Love are way into scents, from the rank gymnasium stench of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” to the Love-penned ode to odors in a recent Mademoiselle. “I’m really interested in smells,” says Cobain. “I think I’d like to own a perfumerie someday.”

“Rape Me,” which carries a quiet biblical angst, is the song the band wanted to play on last year’s MTV Music Awards instead of “Lithium.” Cobain conceived it as a life-affirmative rape song. “It’s like she’s saying, ‘Rape me, go ahead, rape me, beat me. You’ll never kill me. I’ll survive this and I’m gonna f**king rape you one of these days and you won’t even know it.'”

Nirvana has been an active, outspoken promoter of social causes, openly condemning homophobia in print (“I’m definitely gay in spirit and I probably could be bisexual,” Cobain told the Advocate, a gay and lesbian magazine) and headlining a recent benefit for Bosnian rape survivors, which was Novoselic’s idea. Cobain hopes In Utero will change the misogyny so endemic to rock’n’roll. “Maybe it will inspire women to pick up guitars and start bands. Because it’s the only future in rock’n’roll. I’ve had this negative attitude for years. Rock’n’roll has been exhausted. But that was always male rock’n’roll. There’s a lot of girl groups, just now, within the last few years. The Breeders and the Riot Grrrls all have a hand in it. People are finally accepting women in those kinds of roles.”

The band’s new album is certain to be scrutinized like a virus under a microscope. Even months before the scheduled release there was a raging controversy. In late spring, word leaked in the Chicago Tribune that Geffen wasn’t happy with the record. One industry insider called it stridently anticommercial in Newsweek. Some say the leak sprang from the band; others say it was producer Steve Albini who complained to a journalist. Albini says that “the rumors of the trouble came from the record company. They were trying to undermine the band’s confidence.” He feels Geffen tried to pressure Nirvana to add some commercial gloss to his defiantly monochromatic production. The band, on the other hand, alleges the remixes had nothing to do with corporate intervention, but that they were the ones who decided the vocals on two songs were too abrasive. (Scott Litt, who works with R.E.M., remixed “All Apologies” and the album’s first single, “Heart-Shaped Box”). Following the Newsweek article on the conflict that exacerbated it further, Nirvana rebutted the media’s claims with a full-page ad in Billboard magazine.

“I was happy with the recording process, for the most part,” Cobain says. “Albini was great but he’s an opinionated guy. Basically the whole media thing was an ego boost for him, a way for him to get out of the fact that he had anything to do with us. He’s so into being Mr. Punk Rock. It didn’t surprise me. He’s an extremely paranoid person. But he may have reason for that… many major labels do f–k with their artists.”

Guttersniping and bickering aside, In Utero was finally given the September 14 release date, and Nirvana is ready for a long stint on the road. “I’m totally excited to tour,” Cobain says. “But we don’t know yet what kind of venues we’ll be playing. We don’t know how well the record will sell. Because of the backlash, and the general negative attitude toward our band the past year, we can’t expect to book arenas.”

They’ve had offers to play with U2, and this past summer rejected a possible $6 million paycheck from Lollapalooza. Instead, they want to tour with a myriad of their favorite bands. The Breeders will open some shows, as will longtime mates Mudhoney, and, they hope, TAD and Sonic Youth. “It can get monotonous seeing the same people for seven weeks,” Cobain says. “We don’t want to take any chances of getting into fights with our friends.”

In the wee small hours of the morning, Cobain is rifling through his record collection. Novoselic left hours ago; the next day he’s going to try to track down a female cello player for a scheduled band practice, and his cleaning lady is coming by early.

Hundreds of records are stacked against the wrought-iron rail that looks over the living room. The record player is perched on an old black trunk. The painting from the cover of Incesticide leans against one wall, a giant telescope in front of it. On the floor, near a big cardboard box overflowing with papers, is a bound black journal with a polaroid of Frances glued to the front, sandy-haired and adorable. “The Bean,” as Cobain sometimes calls her, has flown off with the nanny today to see her mother in England, where she’s playing with Hole at the Phoenix Festival. There are reminders of both of them everywhere: Love’s guitar, painted red with Victorian flowers; her ’70s fake-fur coat in the closet; Frances’ playpen, her stroller, her little dirty baby socks all over the place.

Showing off his records, Cobain appears more at ease. He proudly hands me the cover of one of his Daniel Johnston records, titled Hi, How Are You, and puts it on the turntable. “He’s an insane person, been in and out of mental hospitals… I have a videotape of him playing. He sits down at this organ — you know, the kind Christians had in their homes in the late ’60s, the ones with the colored plastic tempo buttons. He starts crying about mid-way through the first song. It’s just so touching, you feel so sorry for him, but at the same time you’re so intrigued.”

Next is the new Royal Trux record. “It’s basically New York scum rock.” And then “The ‘Priest’ They Called Him,” a record he collaborated on with one of his heroes, William S. Burroughs. “It probably pleases me more than it pleases anyone else.” Burroughs’ familiar warble comes on and Cobain’s feedback wails underneath.

He passes me a Wipers record. “I got this in Europe.” And then a Meat Puppets album. “Leave that out,” he says to me, “we’re gonna do a cover of ‘Lake of Fire.'” There’s the Kyoto monks, and a Half Japanese record. “Jad Fair is gonna open for us a few times in the fall.” A very worn copy of Revolver balances against the brown box in the center of the room, and there’s a smashed Knack record near where Cobain squats, flipping through vinyl.

He loves the new PJ Harvey record. I put on the new Hole EP, Beautiful Son. On the cover is a school picture of a young Cobain, framed by pink and blue bows. “No one’s supposed to know it’s me,” Cobain confides. Love sings, “What a waste of sperm and egg.” “Man, if I could get that girl to publish her poetry, the world would change,” Cobain beams.

He holds up The Flowers of Romance by PiL. “This is a great record, it’s just totally uncompromising. It’s a bunch of drum beats, Johnny Rotten yelling over it all, but it works somehow.” Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols follows. “This is still the best-produced record in the world. I want to work with the guys who produced this on our next record.” He sits back on his ankles. “But if they’ve been progressing with technology, their production might suck now.”

He grabs a Smashcords record. “I found this in Aberdeen.” Then Black Sabbath’s Born Again. “They got Bill Ward out of the asylum to play drums.” I tell him I like the cover, a purple-and-red devil baby. He tells me his mom didn’t want him to have the record in the house, that he had to hide it.

He picks up Mark Lanegan’s solo record. “He has the greatest voice.” A Jandek record is next. On the cover there’s a very blurry photo of a man sitting in a lawnchair. “He’s not pretentious,” Cobain says, “but only pretentious people like his music.”

Cobain says he listened to the Shaggs’ Philosophy of the World (Third World) every day for months. The three girls on the front have ’60s hairdos and wear plaid pleated skirts. “The first records are good but then they started taking it seriously and really trying to learn how to play their instruments and it wasn’t as good.”

He moves to the far wall. “Time to get the Leadbelly records out.” Cobain hands me one, a deep blue duotone adorning the time-worn jacket. “I think he’s still most popular among intellectual Jewish communists from the East Coast,” he says jokingly. One of the rarest of his Leadbelly records is cracked, and he explains Courtney isn’t always so good at taking care of records. Recently, Cobain says, a lawyer representing the Leadbelly estate phoned up, offering him the only guitar Leadbelly ever had. “But it was $500,000. I can’t afford that.” He shrugs his shoulders, moves over to another stack of albums, and smiles sarcastically. “I just wish there was some really rich rock star I could borrow the cash from.”