Descending into the dank PATH train station on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, I’d barely heard of Hoboken other than in terms of it being Frank Sinatra’s hometown. I paid my 30-cent fare at the turnstile and traveled through the tunnel under the then-filthy Hudson River for 20 minutes or so, eyeing the businessmen and occasional student types on the journey. Finally climbing the stairs at the other end, I emerged into the bright light of day in another world. It was as if the train had transported me not only far from Manhattan, but far from the current year as well, turning the clock back 20 years or so in those 20 minutes. A total time warp. The town that time forgot…

Arriving in New York City at one of its lowest points in history, the winter of the 1970s, was culture shock in itself, but I was fast approaching the big 2-0 and with a promising new decade ahead I was up for anything. The glitzy disco revolution was nearing the end of its decadent peak, and I myself was starry-eyed with the gritty anti-glamour of the CBGB scene then in full force.

I had answered an ad in the Village Voice. “Band seeking guitarist into Velvet Underground, Talking Heads, Television…” I was living in Brooklyn with a band called the Laughing Dogs, early CBGB stalwarts who I had met in my hometown in Tampa when they were on tour backing up the Monkees. “Why not move to New York and stay with us at our loft?” they had suggested. Indeed, why not? The minute I arrived up north that snowy first winter I started looking for any opportunity to be in a band myself. This ad sounded promising.

The guys who had placed it — Glenn Morrow, Rob Norris, and Frank Giannini — all lived in New Jersey. We clicked at the first meeting, and started practicing pronto. A few months later, when the Laughing Dogs decided to sell their loft, Glenn offered me a room in his three-bedroom Hoboken apartment — a sixth-floor walk-up on Hudson Street near 11th, across the street from the imposing Maxwell House Coffee factory, just behind the giant neon sign (the largest in the world at one point) facing Manhattan with its mammoth coffee cup dripping neon drops into the Hudson. I loved the town, the apartment, even the caffeinated air emanating from across the street. I moved into what would be my home for the next five years as we started the band — soon called “a” — that later morphed into the Bongos.

Also Read

Compact Discs: Sound of the Future

Only a couple of miles away from midtown Manhattan, the city of Hoboken was a distant star, light years from the high-pitched frequency of New York City, and had a particular kind of beauty that comes from being “authentic.” The quiet streets and storefronts had barely changed since they served as the location set for On The Waterfront, almost as if it were a fading Disney theme park of an American town of the 1950s: clothing stores with mannequins and displays that had been in place since the mid century (there was little need for “vintage” clothing shops — they practically all were); mom-and-pop cafés and diners; and blue-collar families of Italians, Irish, and Puerto Ricans who worked in the coffee factory or other industries in the mile-square radius, mingling and milling casually along the main drag of Washington Street. Not much hustle-bustle. Oh, and the bars. Although not very Disney-like, there was at least one bar on every corner, sometimes one on all four. Ninety-seven or so bars in those 14 blocks. All had been connected at one time via an intricate underground tunnel system that allowed Hoboken to be surreptitiously stocked during the dark dry days of prohibition. This town was serious about its drinking.

Maxwell’s Tavern, barely a block away on Washington Street, had been purchased recently by the Fallon family, who converted the space from a dark, workingman’s bar to a bright bistro serving salads and quiches with a cool ambience similar to one you would find in SoHo: Hanging plants, lots of wood, and shiny brass at the bar. It was Glenn Morrow’s idea for us to ask Steve, the young co-owner and sincere fan very in-tune with the current wave of bands and trends (this was the era of Joy Divison, A Certain Ratio, Gang of Four; the fierce beginnings of indie rock.), if he would be interested in bringing live music to his new venue — meaning, us. With hardly any shows under our belts, Steve took a gamble and said yes.

So, on one weekend night in October, 1978, “a” set up and played our new, idiosyncratic tunes right there in the restaurant, our backs to the big picture windows facing Washington Street, at which a crowd soon gathered. Other than jukeboxes, an occasional combo, or “Gene the Singing Plumber,: the town had not been a swingin’ pop Mecca since Ol’ Blue Eyes had skipped town. Hobokenites of all ages were looking in curiously at this alien development — the newly transformed Maxwell’s was throbbing with raucous, live music. We played with enough gusto to rattle the delicate wine glasses and hefty beer mugs off their shelves and crashing to the floor. The feeling that something could be starting here became apparent.

Soon, there were shows and growing crowds in that front room every weekend, just like a real venue.

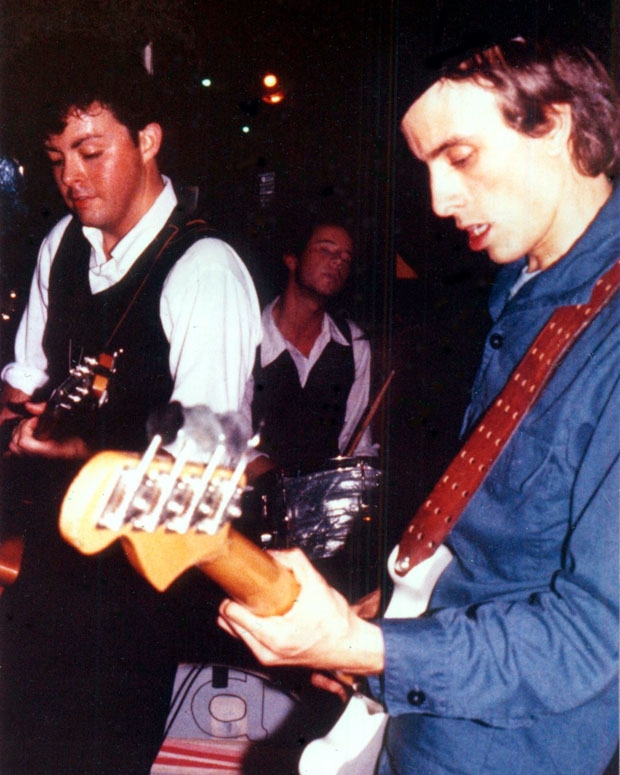

After several months, “a” splintered. Glenn pursued journalism with the New York Rocker and later founded the Individuals and Bar/None Records. Rob, Frank and I became a trio, using the dark back room as our incubator for rehearsals, and eventually re-emerged a few months later as the Bongos. Our first show was in the front room, opening for the Fleshtones. But at some point, we started inviting friends and regulars to hang out at rehearsals. When Steve noticed the vibe that was happening in the back, it became clear that the neglected storeroom easily could be set up for shows.

Applying a fresh coat of paint, polishing up the back-room bar, and adding a sound mixer/DJ booth, the place was transformed. Our practice sound system and the casual air of community that existed at the beginning remained throughout Maxwell’s heyday years. It was rare, then and now, to experience a venue where the separation between performer and audience was less distinct. The lines blurred. Because the newly built stage was low to the ground, and the room so small (200 people was jam-packed), the synergy was palpable. What happened off the stage was often just as entertaining as what happened on. One night, the young owner of British indie label Fetish Records saw us play, and signed us then and there, resulting in the first Bongos album, Drums Along The Hudson, in 1982.

Things happened fast after that. The back room of Maxwell’s caught fire, in the way that great pop stars catch fire. The bright lights of media exposure descended upon the small town and the small club. Television crews, The New York Times, national magazines like Musician, all covered the Hoboken scene simultaneously. The Bongos signed to a major label (RCA Records), added fourth member James Mastro, and soon we were darlings of the fledgling MTV, where we were always announced as “Hoboken’s Favorite Sons.” Like Athens, Georgia, and later, Seattle and Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Hoboken was, for that moment, the “it” town. A parade of the most important bands of our era played in that little back room, from Nirvana and New Order to, well, basically everyone. All were drawn to it because it was truly special. In an era of artifice and image, it was truly real, almost humbling.

But with ascension came inevitable decline. By the mid-’80s, the Bongos were on tour for more than 300 shows a year, and each time we came home to Maxwell’s for a joyful homecoming we could sense change. As Hoboken grew, gentrified, and its rents increased, the innocence and unique characteristics fell away one by one. Instead of mom-and-pop stores, the chains came in. Sidewalks seemed suddenly overcrowded. The blue-collar families were replaced with a new wave of aggressive professionals; artists and musicians were squeezed out to make room. Now, rowdy sports bars overtook Washington Street as weekend traffic and parking became unbearable. The Fallons sold Maxwell’s, and the new regime soldiered on, but times and needs had changed. Maybe most importantly, indie rock was now the mainstream, and no longer the alternative.

Regardless, a lot of great music and unforgettable shows were still to come. Even as the city around it changed, Maxwell’s somehow held onto its integrity and stayed cool way longer than any of the New York City clubs that could be considered its contemporaries. Maxwell’s itself was a star, bright as the sun. In its orbit were the many bands that played there and the colorful regulars. And for the city of Hoboken, Maxwell’s served as a cultural center: a noisy little corner of civic pride, ever-changing and full of surprises. And, like its namesake, to the very end it was “Good to the Last Drop.”

Richard Barone will reunite with the Bongos and “a” to perform at Maxwell’s final show on July 31. He is still a recording artist and performer, as well as a producer and author. Since his days as frontman for the Bongos, Barone has worked with artists from Lou Reed to Pete Seeger. He now lives in New York City’s Greenwich Village, where he is a professor at New York University’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded Music.