The Big Star story, steeped in both myth and the music recorded in Memphis’s Ardent Studios, is far from a straightforward tale. Beginning in 1972, the quartet — guitarists-vocalists Alex Chilton and Chris Bell, bassist Andy Hummel and drummer Jody Stephens — released three distinctly crafted, contemporarily ignored albums, with Bell leaving after #1 Record and Hummel departing after 1974’s Radio City, leaving just Chilton and Stephens to record Third/Sister Lovers, the band’s devastating finale. But by the late ’80s Big Star was being repeatedly name-checked as an influence by the likes of R.E.M., the Replacements, and Teenage Fanclub, plaudits that propelled the band to cult status a decade after its final songs were recorded.

Bell passed away in 1978, and Chilton and Hummel both died in 2010, but over the years Big Star books, a multi-disc box set and tribute concerts have increased the band’s profile in fits and starts. Now, after a lap around the indie film festival circuit, Nothing Can Hurt Me, the first full-length Big Star documentary, will be released on July 3. (The film’s soundtrack will be released June 25, and on June 30 an all-star line-up, including Sharon Van Etten, Kurt Vile and Mike Mills, will perform Big Star’s Third/Sister Loversin New York’s Central Park).

We spoke with director Drew DeNicola and drummer Jody Stephens about the film, the band’s legacy, and the enigmatic Alex Chilton.

Drew, at the beginning of the film Hot Chip’s Alexis Taylor says, “It’s a strange history. You have to do a lot of explaining of who this band is.” And those are his words, not yours, but that feels like a thesis statement to me.

Drew DeNicola: Exactly. I mean, I was so glad he said that. That introduction was a new one that we made recently, because we felt like we wanted to try to bring in the uninitiated and explain why the story is almost an anti-rock band bio. You know, the band kept changing. You’ve got four guys on the first record, then three and then two, and the records were all, I think, uniquely different. There was so much experimentation going on in what their sound was going to be. And then finally the band was really appreciated retrospectively. You know, the fans of Big Star never really came in contact with Big Star so to me it just kind of turned the whole idea of a rock band on its ear, and I found that really interesting and challenging. I got really tired of “the founders of power pop”; “the Replacements and R.E.M. loved them.” Sure, that’s part of it, but there’s just so much else. And the relevance of the term “power pop” today, I just don’t even know what that means anymore. And I know it didn’t mean anything to Alex and Jody and Chris and Andy in 1971, so I feel like I wanted to debunk that moniker a bit.

Well, great. Now I can’t use power pop in my introduction. Thanks for that.

DeNicola: [Laughs] Sure.

Let’s talk about bringing in the uninitiated. You guys did the Kickstarter thing near the end of the project, and there’s some outreach involved with that. How do you describe the film to someone who hasn’t heard Big Star?

DeNicola: It was very frustrating to have to explain it. You know, it was almost like you’d be fishing. You’d say, “Oh, Big Star, they were this band from the ’70s. You know, Alex Chilton from the Box Tops.” And they’d be like, “Oh, the Box Tops. Name me a song.” “‘The Letter.'” “Oh, ‘The Letter.’ Yeah, yeah. So that guy had a band after?” But that doesn’t really explain a whole lot, and then you’d say, “You know that song from That ’70s Show? The guys that did that song.” But, I mean, that’s just a horrible way to try to get people interested in this band, so you have to fill in a lot of details. And that’s what I realized, is that the story was all in the details. The story was all in the uniqueness. It was all in the fact that this band that was, you know, strangely on Stax Records and Stax Records had Isaac Hayes. Hot Buttered Soul was at the top of the chart. And they suffered along with Stax, so that was part of why the record didn’t succeed. And the sound that they were making was a little bit out of place for Memphis, and really a little bit out of place for 1972. And so you need someone to give you a little bit more time to explain the band’s story.

Jody, you’re still a musician, you still live in Memphis and you still work for Ardent. Do you ever run across anyone who doesn’t know about Big Star?

Jody Stephens: Frequently. I’ll be having a conversation and someone will walk up and say “Hello” and they’ll introduce me. And they’ll say, “This is Jody Stephens. He was in a band called Big Star,” and I’ll see a blank face. And it’s like, “Hey, it’s okay. You know, not very many people knew who we were.” It’s okay not to know who the band is.

DeNicola: Jody’s gotten used to it, but I didn’t get used to it. It was just crushing to me, especially in the film festival circuit. In music circles it’s a little bit different, but when you’re at a film festival it would just be like crickets when we would mention Big Star. And I think along the way I started to pick up on that and say, “You know, we’ve got to find other ways to bring people into this story.” There’s just no reason not to love this band. They’re a retrospective classic. When I was in college my CD stand was like Beatles, Beach Boys, Big Star, Byrds, all together. And they slid in there really nicely. Even Douglas Hart from the Jesus and Mary Chain said that there was a whole new interest in classic music in the mid-’80s where they listened to Beach Boys’ Smiley Smile, girl groups and Big Star, you know. So it all kind of happened at once.

Jody, when somebody comes to you and says, “I want to make this movie about Big Star,” how much do you need to know about what these guys want, what they’re planning to do, before you decide, “Yeah, I think that’s a good idea to make a movie about this band that I was in”?

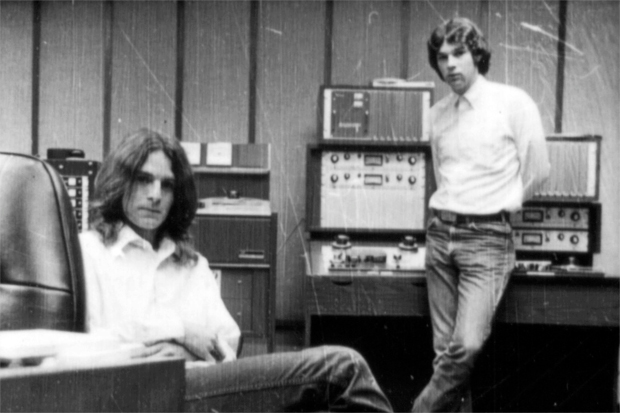

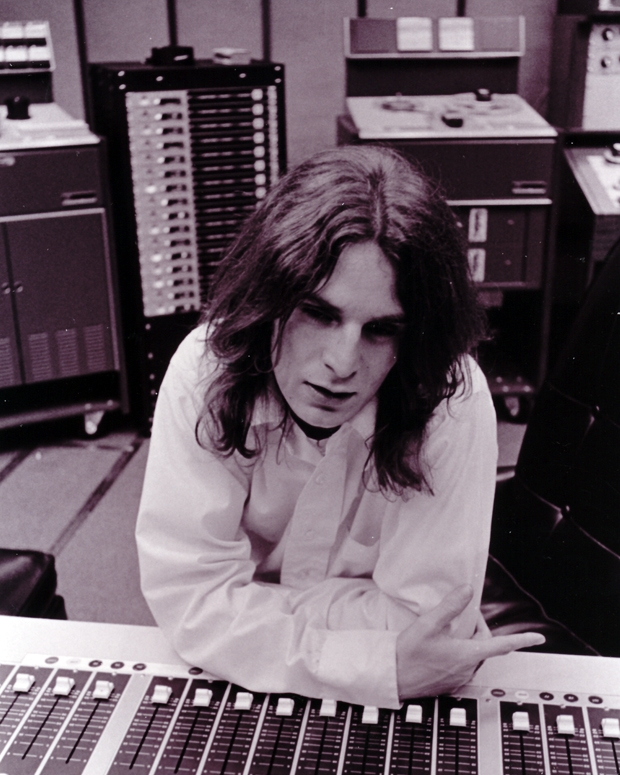

Stephens: Well, the initial gatekeeper was John Fry. You know, John is the owner of Ardent Studios still, and was Big Star’s mentor and engineer. So I think John got a really good vibe from [the film’s producer] Danielle McCarthy, and I just followed John’s lead because John’s pretty discriminating in his choice of folks that he’ll work with. I didn’t really have to think twice about it because John had done the research. And discriminatingly so.

Drew, you get the active participation of Jody and John Fry and [photographer] William Eggleston and his family, and those are all significant parts. Once you decided you were going to make the movie, was there anything that would’ve made you stop?

DeNicola: I mean, in the beginning I was absolutely petrified to do the film, because every time I looked there were just all these issues. Just the fact of very little footage, the fact of so many people not being around anymore. You know, there was about a year period where we were just going back and forth with Alex Chilton, who was absolutely delightful but just kind of made it very clear in the beginning, like he just kept saying, almost like a mantra, “This is not the sort of thing I’m inclined to do.” But he never said “No” definitively, so we were kind of waiting for that for a while. And then Alex passed away and we were already booked to go to South by Southwest, and so we shot that tribute show. And then even from there, there were issues. I mean, John Fry could’ve backed out all along the way, and to me the story of Big Star is the story of Ardent Studios. That’s the commonality amongst all those records. They were all made there, and they were made by a scene of people around that studio.

Jody, let me ask you about Alex’s lack of participation. He had mixed emotions about Big Star, and even though it was just the two of you by the time of Sister/Lovers, Alex is the last one to join the band in beginning. Do you think his mixed emotions come from feeling that Chris had created the Big Star template, and even though Alex was writing his own music he was working within Chris’s framework even after Chris left the band?

Stephens: Well, it’s hard to address that because, you know, it’s true. Alex joined the band that Andy and Chris and I had, and the first album was primarily Chris’s vision in terms of production and the approach and that sort of thing. Alex, of course, played a major role in writing, and probably musically, but it really was Chris’s kind of production vision for that record, and John Fry. Outside of that, I don’t know. I never spoke with Alex about whether he did or didn’t try to pursue a template that maybe Chris had established but, you know, looking at Radio City, so much of that is Alex’s input and guidance, and Andy Hummel’s too. I think Andy probably played a bigger role in that record than a lot of people think. So I don’t know if Alex was kind of looking over his shoulder at that.

Drew, Alex was almost certainly the most famous member of Big Star, so it feels like you made a special effort to show Chris Bell’s role, that from the beginning this was Chris Bell’s band. Is that a priority from the start or is that something that occurs to you while you’re filming?

DeNicola: It didn’t even occur. It was just fact. It was fact-based. I mean, as we were learning more it just was very clear that that Big Star was Chris Bell’s brainchild. It was like his dream group. It was his supergroup. Maybe that’s why it was called Big Star and #1 Record and all this stuff. I mean, it was the group that he wanted to have. He had been planning it since he was in his room when he was 15. I think that was also the impact that Chris had on Alex. I wish the film could’ve gotten that across better. We didn’t have the primary sources to tell you, but I think that Alex was trying to find himself musically in 1970, ’71, and Chris Bell gave him a path. You know, “In the Street” started out as a Delta blues riff on an acoustic guitar that Keith Sykes showed to Alex, and that became a power pop classic. So that’s Chris Bell’s influence. And what I thought was really revealing, and it’s in the film, is we have all these little tidbits of the band doing overdubs in the studio. I listened to them over and over again, and all I can tell you is that Chris Bell was running the show. He wasn’t this diminutive, quiet, sitting-in-the-corner kind of guy. He was really clever and had this wry wit. There’s a line that we used that I thought was very Chris and Alex. Alex says, “Where do I stand in relation to this mike?” And Chris just says, really flatly, “Uh, in front of it.” That was the way it was the whole two or three hours of tape that I listened to. Alex was deferring to Chris a lot. I just wanted that to be known because I don’t want to paint Chris as like this tragic mythic figure. He was actually magnetic. I mean, that’s what I kept hearing from people. He was a magnetic personality.

And, of course, John Fry’s contribution can’t be overstated.

Stephens: Mike Mills tells a story, and it was true for me, which is why I connected with what he was talking about. At the time, you know, there was Led Zeppelin and there was Yes and there were all these really amazing performers. The Beatles. And they were so far beyond what I could contemplate doing, that sort of production and what they had at their disposal with George Martin and Geoff Emerick. Actually John Fry was our Geoff Emerick. John was brilliant. But in terms of the studio and the instruments there at Abbey Road, what the Beatles were doing was amazingly sophisticated. I think Mike Mills said it was kind of a pie in the sky sort of thing. And then he said, you know, Big Star came along and he thought, “Well, this is something that we can do.” And that meant a lot to me, because it was pretty much what I was thinking about that period of music myself, and in some respect why I think we didn’t succeed at that time. Given what was on the radio and the sophistication of all that, in a way what we were doing was simpler, you know, on the surface of things. But melodically I think it was pretty sophisticated. Anyway, I enjoy Mike Mills’ story, that Big Star was something they could do.