The British folk-rock boom that began in the late 1960s, in retrospect, was inevitable. You’d had American folksingers and roots bands, starting with Dylan, going electric, sifting through Folkways comps, curious about hillbilly music and the night old Dixie got driven down. You’d had Brit blues-rock bands, starting with the Stones, excavating riffs and words from the Mississippi Delta and the South Side of Chicago. Wasn’t long before the Animals put those urges together and dug up an ancient brothel ballad that Dylan and other Americans had dug up first. And then more Brits — Donovan, Yardbirds, Beatles and Stones like always — got interested in Eastern modes and bought sitars. Just a short leap from there to figuring out that ye olde Isles themselves had centuries of history worth exploring. Medieval lutes, Morris dances, reels, jigs, schottisches, hornpipes, madrigals, Anglican hymns to St. George, whatever: The roots of Appalachia, some of it, but with crusading scales and minor keys mysteriously intersecting the Middle East. An explosion of pastoral, plucking, whimsical, tradition-mutating British folk rock — groups like Pentangle, Fairport Convention, and the Incredible String Band — followed. But this movement, detailed in the eight records below, would only be the first part of a long tale. This music begat Led Zeppelin and Jethro Tull’s acoustic sides; Celtic rock starting with Horslips (who at their brawniest sounded exactly like Tull crossed with Thin Lizzy) and advancing in drunken punkness through the Pogues and Irish-America’s Dropkick Murphys; the acid-commune freak-folk of the mid-2000s; troll-under-the-bridge folk-doom metal; platinum preach-rock hacks Mumford and Sons and their West London fellow travelers Johnny Flynn and Laura Marling. But for now, hark — Stonehenge awaits!

The Incredible String Band

The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter (Elektra, 1968)

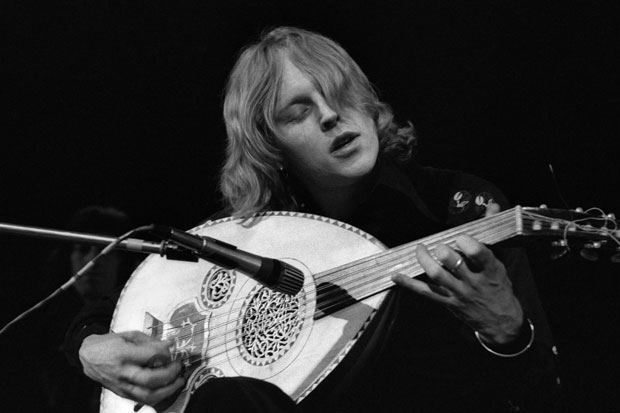

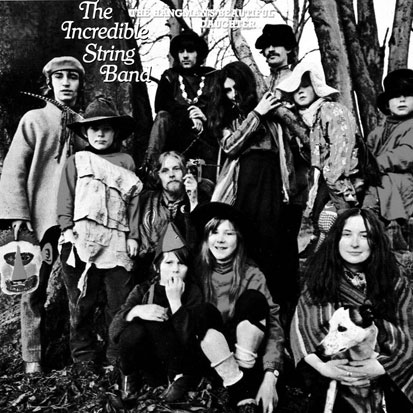

Might not be a stretch to suggest (especially considering Donovan) that British folk rock started in Scotland at least as much as England. The Incredible String Band materialized in Edinburgh and Glasgow circa 1966. Their third and most acclaimed album, with core twosome Robin Williamson (lead vocal on his own compositions, plus guitar, gimbri, whistle percussion, pan pipe, piano, oud, jaw harp, chahani, water harp, harmonica) and Mike Heron (lead vocal on his own compositions, plus sitar, Hammond organ, guitar, hammer dulcimer, harpsichord) assisted by a few friends (including a finger-cymbalist named Licorice), reached the Top 5 in the U.K. The cover art features 11 people — including at least five children — and a dog, posing in an autumn forest in very colorful costumes, presumably celebrating some joyous sort of prehistoric harvest ritual. And that’s what most of the music sounds like: whimsical odes to Minotaurs, witch hats, and the new moon, complete with nature sounds, pagan funeral chants, extended drones, and plinky-plonky ambient parts. Plus, “A Very Cellular Song” which, in just under 13 convoluted minutes, jousts backwards from a gospel spiritual to deep thoughts about the size of amoebas.

Also Read

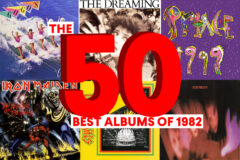

The 50 Best Albums of 1982

The Pentagle

Basket Of Light (Reprise, 1969)

Pentangle guitarist Bert Jansch and the Incredible String Band’s Robin Williamson had both performed traditional folk as regulars in the same Edinburgh bar early on. But the Pentagle were a full quintet (hence their name), and their lineup — couple hot guitar players (who double on banjo and sitar here), woman with a beautiful voice (Jacqui McShee, in their case), and rhythm section — sort of set a Brit-folk template. Their omnivorousness also swallowed influences from baroque to blues, jazz to the Jaynetts. The Pentagle interpret that Bronx girl group’s 1963 hit “Sally Go Round the Roses,” not long after both Grace Slick (in the Great Society) and Joan Baez had done it. And it fits right in, too: The lyrics obviously owe a lot to the Black Plague-inspired “Ring Around the Rosie”; another track here, “Lyke-Wake Dirge,” is said (in the liner notes) to be a pre-Chistendom English poem whose imagery lives on in “Hopscotch” and “London Bridge Is Falling Down.” In at least two other instances, the Pentagle reclaim for Britain songs Americans had altered; one of those, “House Carpenter” (done on The Anthology Of American Folk Music by Clarence Ashley circa 1930), evolved out of the Satanic romance “The Daemon Lover”: “My soul is bound for hell.” So Brit-folk’s occult obsession is hence conjured.

Fairport Convention

Fairport Chronicles (A&M, 1976)

British folk rock’s most important band were even less purist than the Pentagle. Their definitive compilation — 20 cuts drawn from eight albums, including spin-offs by Fotheringay, the Bunch, and Sandy Denny, all released between 1968 and 1972 — includes two adaptations of traditional numbers, but also songs written by Buddy Holly, Dion DiMucci, Bob Dylan (twice), and Gordon Lightfoot. The three gatefold pages of explanatory liner notes reference Jefferson Airplane, the Byrds, and Buffalo Springfield as Fairport inspirations, as well. Chronicles is arranged more by emotion than chronology: With “Tale in Hard Time” and Denny’s stark “Who Knows Where the Time Goes,” the album doesn’t exactly start out on an optimistic note, but “Walk Awhile” and the sloshingly loose “Million Dollar Bash” are clearly meant for drinking and dancing. By “Genesis Hall” on side four, though — “Oh, helpless and slow, and you don’t have anywhere to go” — even the alcohol abuse feels desolate and obliterating. Then soon comes genius guitarist Richard Thompson’s “Sloth,” one of history’s all-time powerful call-to-arms dirges — “just a roll on the drum, and the war has begun.” A depressing gravity, made sturdy for future centuries.

Comus

First Utterance (Dawn, 1971)

Comus resided on the extreme art-prog end of the Brit-folk continuum: beyond Tyrannosaurus Rex, beyond the Strawbs, beyond Gentle Giant, beyond Renaissance. They always had a cult — David Bowie had them open for him back then; people in Opeth and Current 93 and sundry freak-folkies worship them now. But they presumably never had any hopes of a mass audience, given both lyrics of extreme violence (their single “Diana,” more than a decade before Hüsker Dü’s similarly themed “Diane,” is a rape story) and feral vocals that suggest Yoko in Beatle-breakup-vibrato mode dueting with Bilbo Baggins auditioning for Rush. Or maybe Björk joining Cradle of Filth? The music’s out there, too: Leaky waterfalls (in “Drip Drip”), Iron John drum circles, hobbits banging on tree stumps and toadstools, maybe a fiddle or two being electrocuted.