The most radical turn in rhythm & blues history occurred in the early 1980s: the shift away from self-contained bands who carried their road sound onto records. This development happened in the wake of disco, early rap, Prince, Michael Jackson, and innovations in sampling and studio technology. And it effectively ended an R&B tradition you could trace back through P-Funk, Sly and the Family Stone, James Brown, Louis Jordan, all the way to Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five in the ’20s, at least. Of course, it’s easy to get stupidly nostalgic about the loss of “real musicians playing real instruments” — and it’s not like last-bands-standing the Roots and the Dap-Kings have made better music than everybody else on the planet in the past quarter century. Plus, R&B always had other traditions anyway: label “house bands” from Motown to Sugar Hill, producers shaping sounds, singers and vocal groups backed by session hands. Still, it’s enlightening to focus on the final decade where actual bands helped rule black popular music. Chic, the Time (whose albums were mostly played by Prince anyway), Cameo, and the Gap Band, you should already know about; Washington, D.C. go-go combos like Trouble Funk probably deserve their own separate category. But who knows — even cranky “real-band” purist Joe Carducci, of Rock and the Pop Narcotic treatise fame, might approve of the eight ’80s albums below. If you can’t be rockist about R&B, what can you be rockist about?

Fatback

Hot Box (Spring, 1980)

This Brooklyn ensemble was named by drummer Bill Curtis for a jazz rhythm named after the cut of pigmeat responsible for pork rinds and slab bacon, and they had high-cholesterol funk to match. They put eight albums on the Billboard 200 between 1976 and 1982; this, their highest, peaked at a just No. 44, and zero of the 30-or-so singles they placed on the R&B chart between 1972 and 1985 crossed over to the pop Hot 100. In the ’70s, those included songs about doing the bus stop and doing the Spanish hustle and (four years before Frankie Smith’s “Double Dutch Bus”) doing the double dutch. In 1979, they had the foresight to put a rapper on their record, and “King Tim III (Personality Jock)” beat “Rapper’s Delight” to the racks by several months. Supposedly, Fatback were past their peak by then (“On the downward spiral” and not loved much by MCs up in the Bronx, David Toop reports in his early hip-hop history Rap Attack), but you’d never know it from the excellence that is 1980’s Hot Box. The title refers to the big portable radio on the cover (maybe too cheery-looking to blast the ghetto — and the subway graffiti on the wall isn’t too convincing either — but they were trying), and also to a certain female body part in the big-bottomed title track. “Love Spell” drips just as much juicy groove, but on side two they move beyond mere funky filler, starting with two Top 10 R&B hits: The partly cartoon-rapped “Gotta Get My Hands on Some (Money),” which embraced an old-school early-Reagan recession theme that nobody talks about much anymore — see Prince Charles and the City Beat Band’s “Cash (Cash Money),” Divine Sounds’ “What People Do for Money,” “Hard Times” songs on both Kurtis Blow’s and Run-D.M.C.’s debut LPs — and then the farty-keyboarded “Backstrokin’,” about swimming, tennis, massage, your choice. Then they close with the awesome “Street Band,” with lyrics about Harlem kids making summer beats with whatever junk’s on hand, chanting that picks up on both naughty playground rhymes (“bang bang spoon spang”) and the rope-a-dope Ali/African bent of certain subterranean ’70s disco, and horns that feel like a throwback to Mardi Gras parade jazz.

Maze Featuring Frankie Beverly

Joy and Pain (Capitol, 1980)

Just as joyous as Fatback, but way more spiritual and way less grimy, gospel-and-doo-wop-bred Philly transplant Frankie Beverly and his Oakland septet Maze were another black band too uncompromising to cross over to white fans: Seven of the 10 albums they put on the Billboard 200 between 1977 and 1994 wound up in that chart’s Top 40, but they never scored a pop hit higher than No. 67. Every studio album they released landed in the R&B Top 10 and went gold, but none went platinum. Yet, like their apparent role models Earth, Wind and Fire, there was something curiously prog about Maze: Both in Sam Porter’s fancy electric piano and synthesizer doodling in tracks like the smooth-fusion workout “Roots,” and in their album covers, which almost always featured their giant cosmic hand-maze logo and often added mystic topographical vistas — on the back of 1978’s <i>Golden Time Of Day</i>, the band is on a snow-covered mountain plateau; the cover of 1979’s Inspiration displays an interplanetary tundra almost worthy of a Finnish doom-metal gang like Amorphis. As for the musicians, they all look like middle-aged African-American dads; on the back of Joy And Pain‘s sleeve, only guitarist Ron Smith lacks facial hair, and lead tenor Beverly is, of course, wearing his ubiquitous baseball cap. The seven band members’ credits on the cover list grown-man values they care about: “love,” “strength,” “warmth,” “fire,” “inspiration,” “gentleness,” “soul.” The music? Gorgeous, utopian, a nonstop relaxed groove secure in its manliness, embracing “Family” and “Happiness” (two song titles), assuring a mature audience that they’ll survive these “Changing Times,” acknowledging that life comes with both “Joy and Pain” (sampled eight years later, in the similarly named Rob Base and D.J. E-Z Rock hit.) In his 1988 book The Death Of Rhythm and Blues, Nelson George pegs Maze as pioneers of both “quiet storm” and “retronuevo” R&B, praising Beverly’s “working class” refraction of Marvin Gaye, particularly on 1981’s superb double-vinyl Live In New Orleans: “He sounds like a dedicated husband still madly in love with his wife after all these years.” In other words, as reliable as his band.

Slave

Showtime (Cotillion, 1981)

Slave, from Dayton, Ohio, home of the Ohio Players, also had arena-rock in their genes. Their audacious name shoved American history in your face, long before Prince wrote the same word on his; the cover of their 1977 debut album showed a shirtless black man carrying a giant globe on his shoulders. But their first few albums took hard rock guitars into account, in a much more blue-collar, less artsy-fartsy-Zappafied way than, say, Funkadelic. Robert Christgau, in 1977, even compared Slave to “third-generation” mid-American prog bands like Kansas and Starcastle. And on 1981’s Showtime, which rightly seems to be the consensus choice as their most solid album, they even put an arena on the album cover: An outer-space one, no less, with the stage under a glass pyramid. But sonically, they’d toned down their rock side through the disco years. Visually, too: On the back of that ’77 debut, they look like street toughs and sweathogs, with impressive Afros; on Showtime, they’re upwardly mobile, spiffy in sports jackets. Three members had just left to form the group Aurra; lead vocalist and percussionist Steve Arrington would leave after this record to form Steve Arrington’s Hall Of Fame and find Jesus Christ. <i>Showtime</i>is “dedicated to ALLAH for the Concepts of Pure Growth!!,” and post-1981, both spinoff bands would make better albums than Slave would. Here, though, Arrington gives bassist Mark Adams’ muscular throb a more consistent sense of melody than it ever found before. From opener “Snap Shot” (about taking a girl’s picture — for the cover of Life, not porn) to closer “Funken Town” (presumably about Dayton), these are actual tunes, even when they’re just chants. And the funk is the no-nonsense kind, even when the chants are nonsense.

Vaughan Mason and Crew

Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll (Brunswick, 1980)

Not all ’80s funk bands were ’70s holdovers. In February 1981, Michael Freedberg wrote a great essay for a now long-forgotten paper called The Soho News about a now long-forgotten urban street genre called “strut”: “The strut is as much rhythm from the bottom up as disco was about people of the bottom rising to the top.” A few 12-inches mentioned in the piece are early rap; several others might intersect with the kind of post-disco electro-funk that DJs later labeled “boogie.” But the primary focus of “Struttin’ With Some Belly Laughs” was an Atlantic City DJ named Vaughan Mason, who had gone No. 5 on the R&B chart in 1980 with “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll,” an eight-minute disc designed for roller discos (“Rrrrrrrrock…SKATE! Rolllllllllll…BOUNCE!”), built on a Chic bass line, but booby-trapped with multiple conga/bongo/hi-hat/Moog-bass breaks where the musicians improvise while skaters can shuffle in line or spin. The song was immediately sampled by rappers (see Trickeration’s 1980 single “Rap, Bounce, Rockskate”) and has been put to use since by everyone from L.L. Cool J to J.J. Fad to Daft Punk. In 2005, the Lil’ Bow Wow movie Roll Bounce took its name, among other inspiration, from the song. Two other long tracks on Mason’s rarely heard LP (“Roller Skate,” “We’re Gonna Funk You Up”) show his band taking similar extended rhythmic feints and dodges, often with whistles, handclaps, wails, and “baby-bubbah baby-bubbah”s spooned in; sometimes, it sounds like the birth of house music, which later in the ’80s Mason would reinvent himself for, under the moniker Raze. “Cravin’ Your Body” is more tribal and blurry and ominous, reminiscent of ’70s black rock bands like War or the Jimmy Castor Bunch; “Thinking About My Baby” is six minutes of drippy piano mush, the less said about which the better. (Liner note: “This album offers Funk, Ballads and Roller Skating music” — another lost genre!) The four guys on the back cover (out of eight musicians credited in the notes) are a real hoot: disco dudes trying to look cool; a taller dude with a pimp hat actually looking cool; and a very skinny dude with long snaky dreadlocks looking like a serene wise man. According to the Freedberg essay, that one’s Mason, and “onstage he wears a boa constrictor and wishes he was Alice Cooper.” Freedberg claims the Crew’s hit is “the most reggae-influenced funk cut ever to get over,” with negative space worthy of dub; he traces strut’s self-deprecating aesthetic back to “the cakewalk in early jazz.” Nobody else ever picked up on those ideas. But imagine if somebody had?

Skyy

Skyway (Salsoul, 1980)

“Nor are the house party revelers of Skyy’s ‘Skyzoo’ or Grandmaster Flash’s ‘Freedom’ ashamed that when they blast from their kazoos it comes out as babies squalling through pacifiers,” Michael Freedberg wrote in that same strut piece about Vaughan Mason. Skyy was an odd pairing, still possible in the pre-“Message” days: Acclaimed ground-floor hip-hop originator with a co-ed octet from Brooklyn, eventually best known for 1981’s super-cute Top 30 pop bubble-funk hit “Call Me,” where you root for a girl trying to steal her girlfriend’s boyfriend even if that makes her a jerk. The earlier and much stranger “Skyzoo” really did have a kazoo hook wafting through (hence its name), not to mention wacky repeated call-and-response (“Whatcha wanna do?” “I wanna play my skyzoo!”), Jimmy Castor-style troglodyte grumbling, and other disco reference points. It showed up on Skyy’s second album, the title of which you’re forgiven if you confuse with Skyyport, Skyy Line, Skyyjammer, and/or Skyylight (their third through sixth LPs.) Included among Skyy’s eight members were two mustachioed white guys (keyboardist Larry Greenberg and guitarist/keyboardist Anibal Siera) and three singing Dunning sisters (the most zaftig of whom, Bonny, gets the center spot on Skyway‘s back cover). Non-member Randy Muller, who had ’70s bands B.T. Express and Brass Construction on his resumé, did most of the producing/arranging/writing. But really, the group’s bass-plucking, string-surging sleekness was a testament to how much Chic had changed black pop. And the first half of<i>Skyway</i>is relentless, reveling in low-register fuzz, Captain Kangaroo/Mr. Green Jeans namedrops, and swiped ’70s novelty hooks (“Car Wash”/”In The Navy” handclap beats, direct quotes from Castor’s “Bertha Butt Boogie” and Daddy Dewdrop’s “Chick-A-Boom”) over variations on the Chic formula. Side two, in comparison, is a perfunctory but functional coast until the closer, “Music,” where cowbells, guitars, and wolf howls conjure the ’70s rock definition of “boogie,” while one of the Skyy guys fends off a bill collector trying to repossess his Cadillac, blue jeans, and cowboy boots: This ain’t no disco. Later (“Miracles,” 1982) one of the Skyy gals would learn to do a sweet Michael Jackson. For now, this’ll do.

Kleeer

License to Dream (Atlantic, 1981)

More post-Chic New Yorkers — nine of ’em this time, dressed to the nines too, but once again including three lady singers and two white men with mustaches. And like Big Apple Band alumni Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards themselves, Kleeer had a ’70s past playing (allegedly) hard rock: Pipeline, they were called then. You can totally hear remnants of that in the two side-closers of License To Dream, the most middling-successful of the three ’80s albums this band charted: “Hypnotized” kicks off with a Grand Funk cowbell, then turns into a kind of Santana-fied Latin blues with robotic proto-Italodisco shy-girl backup; “Where Would I Be (Without Your Love)” is pop funk verging on yacht rock. But those are nothing compared to the two longest cuts: The 8:17 “Get Tough,” where the players stretch out their buttery jam around comic mimicry of the recently buried John Wayne (three years before “Rappin’ Duke”), and especially the 7:22 “Running Back to You,” where Woody Cunnigham’s hypermasculine blues/soul/gospel testifying counterpoints wild percussion breakdowns and offhand synth squeals. Cunningham heartily throws down in opening theme track “De Kleeer Ting,” as well, and the band pushes hard and fast for this genre — think “Chic Cheer” gone thrash, almost. Except they do soft good, too: The ballad “Sippin’ And Kissin” is way above funk’s why’d-they-slow-down norm, and “License To Dream” is a lush ode to positivity that builds like it senses deep house music over the horizon. So no way will you mix up Kleeer with Klique or Klymaxx, right?

Champaign

Modern Heart (Columbia, 1983)

Is this even an R&B band? Well, they did have two Top 10 R&B singles, both wedding-ready ballads, both pop crossover hits, both pure swooning, cascading genius — “How Bout Us” in 1981 (which also went No. 1 Adult Contemporary), then “Try Again” in 1983 (which is here, and if it won’t persuade you to patch up your relationship, you were born with no soul). On the other hand, Champaign are such clueless Midwesterners they named themselves after their hometown (always a danger sign) — Champaign, Illinois, also home of R.E.O. Speedwagon! European ancestry seems to strongly dominate within the sextet’s lineup, and they are extremely fond of lite Caribbean lilts they seem to have picked up straight from either (1) Culture Club and Haircut 100 videos; or (2) some band that had a residency in the Terre Haute Ramada Inn cocktail lounge; or maybe (3) Lionel Richie (though “All Night Long” was still a few months away, so maybe not). One of their more island-riddimed things is even called “Cool Running,” a decade before that movie about the Jamaican bobsled team! And they follow it with this doo-woppish sort of Manhattan Transfer finger-snapper called “Walkin’,” which nonetheless manages to build momentum and go to church at the end. Side one thus complete, side two then bridges two fluffy ballads with two new wave robo-funk ditties (all the rage in ’83 — even Shalamar were doing it on The Look), the last of which derides “the toys of multinationals.” Champaign, Illinois: Weirder than you think!

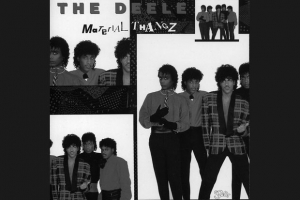

The Deele

Material Thangz (Solar, 1985)

But, of course, the guy who really brought new wave into R&B — and arguably the guy most responsible for the death of R&B bands, given his tendency to play most all the instruments himself — was Prince. The mid ’80s saw zig-zaggy ideas that Prince picked up from the Cars or Devo slipping into black pop across the board, and not many did it better than this last-ditch Cincinnati five-piece. They dressed hip, too: skinny ties, jheri curls, bright collarless shirts. On this album’s cover, pencil-mustached guitarist/keyboardist/vocalist Kenny Edmonds could almost pass for Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott, if not for his herringbone smoking jacket (nothing underneath, natch) that looks almost the same as the one El DeBarge wore on the cover of Rhythm Of The Night the same year. Edmonds was appropriately in charge of the Deele’s DeBarge-type vulnerable, falsetto-croon songs; the Deele would get a top 10 pop hit with their loveliest one, “Two Occasions,” three years later, perfecting a changing-seasons motif he instigates on this album’s “Sweet November.” Slow ones, though, aren’t what Material Thangz is about, which might help explain why it was by far the least lucrative of their three albums, despite probably being their best. “Let’s Work Tonight,” “Stimulate,” “Sweet Nothingz,” and the title track are irresistibly elastic and boisterous machine-funk, working the kind of rubber-band beats and sarcastic asides that Prince had concocted on Controversy,but had mostly shelved by Purple Rain; poor-guy/rich-girl rom-com “Material Thangz” itself also seems to nod to Madonna (who’d just scored with “Material Girl” a few months before), and “Suspicious” aims the gothic-horror-sound-effect paranoia that Michael Jackson was ruling the world with at a crafty lady stealing their stuff. Distrustful Deele tracks like that one also feel like blueprints for new jack swing and producer-driven pop R&B to come — which seems apt, given that Edmonds would revive his Bootsy-granted nickname Babyface before long, and he and Deele drummer L.A. Reid would soon be creatively charting R&B’s future at LaFace Records and beyond. Bobby Brown, Boyz II Men, Paula Abdul, TLC, Mary J. Blige, <i>The Bodyguard</i>, Mariah Carey, Pink, Rihanna: On their way. Bands? You had your day.