Like a lot of things during that weird pre-Nirvana window when disposable cassettes were retailers’ favorite format, a prevalent turn-of-the-’90s prediction about our sonic future soon fell through the cracks: Namely, that newfangled sampling technology would knit music into a quilt of all kinds of other music. Pop, as one over-conceptual British band of the time put it, would eat itself. The germ of that idea had been around since Eno and Byrne’s 1981 My Life In the Bush of Ghostsor even Buchanan and Goodman’s ’50s “Flying Saucer” novelties, but ’80s hip-hop made it seem like more than a lark — “Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel,” also from 1981; Double Dee and Steinski’s “Lesson” mixes; early albums by Public Enemy, De La Soul, the Beastie Boys. Wax Trax industrial, the Residents, Age of Chance, and dub reggae (particularly Adrian Sherwood’s kung-fu production of people like Mark Stewart and Tackhead) figure in as well.

And by 1988 or so, certain wise-guy artists were making danceable collages their entire reason for being. That objective never totally went away, but before long, copyright lawsuits drove montage music into the shadows — increasingly subtle micro-snippets (DJ Shadow, Avalanches), increasingly grey-market bootleg mashups (Soulwax, Girl Talk.) Hip-hop producers consistently stayed years ahead of everybody else. The eight albums below, though, come from a time when the sampledelic playground was still being staked out — and several of these records found commercial success there, even if everybody’s long forgotten they existed.

Todd Terry Project

To The Batmobile, Let’s Go (Fresh, 1988)

Though Brooklyn-born, Todd Terry is probably bricolage music’s most direction connection to Chicago house: He was spinning it, along with Italo disco and ’70s standbys, at venues in New York right when it was happening. With his 1989 Jungle Brothers collaboration “I’ll House You,” he also played a fairly huge role in inventing hip-house (which dominated pop radio in the early ’90s more than you might remember — think Snap!, C&C Music Factory, Technotronic). And the 12-inches he made as Royal House, Orange Lemon, and Black Riot, even when less than memorable, always explored new chemical compounds. He was one of the first non-Chicagoans to get confusingly classified as “acid-house.” And on this debut album, he jumbled detached vocal tics and jazz-rock flutes and zany bass burps, dropping science like Galileo. There’s even a New Age instrumental called “Sense.” But the two real club classics are “Weekend” and “Bango” — the latter basically a missing link between Arthur Russell/Dinosaur L’s amazing 1982 “#5 (Go Bang!)” and Prince’s 1989 No. 1 single “Batdance,” possibly the Purple Slurple’s worst hit ever. Which wasn’t Todd’s fault.

Also Read

The Reissue Section: Winter 2021

Coldcut

What’s That Noise? (Tommy Boy/Reprise, 1989)

These two geeky-looking British gents — one who used to program computers, one who used to teach math — actually had their greatest moment with 1988’s James Brown/Ofra Haza/Don Pardo/Peech Boys/Salsoul Orchestra-sampling “Seven Minutes Of Madness” remix of Eric B. and Rakim’s “Paid In Full.” Translating such mind-blowing mosaic-making into an entire album was tricky, so they lured some lively voices to talk and/or sing on top: the Fall’s Mark E. Smith, Black Uhuru’s Junior Reid, Queen Latifah, up-and-coming Brit-soul diva Lisa Stansfield. Result: Cunning collisions that beg to be blasted loud, with drums doubling the groove and go-go, house, and worldbeat rhythms melting down. Tarzan and George Jetson stop by, too. “Beats And Pieces” pays homage to a venerable and largely bootleggish cutup series apparently initiated by Sly and Robbie in 1981, and “Adventures on the Wheels of Steel” itself gets steel-wheeled.

Colourbox

Best Of 82/87 (4AD, 2001)

Two brothers surnamed Young (but not the ones in AC/DC), augmented by shifting, weightless female voices, Colourbox were southeast Londoners obsessed with dub reggae and breakdance-y electro-funk before such obsessions turned commonplace. “Today, in the wake of the whole techno, trip-hop, and electronica revolution, it’s almost standard for bands to comprise a pair of faceless technocrats,” the now 11-year-old liner notes explain. “Back in the early ’80s, however, such outfits were on thin ground.” They were known to cover Augustus Pablo and U-Roy and nod to Jamaica’s obsession with spaghetti westerns (in 1985’s “Looks Like We’re Shy One Horse – Shoot Out”); they even created a “World Cup Theme.” But in 1987, when 4AD co-founder Ivo Watts-Russell persuaded them to unite with proto-post-rock/acid-house oceanic dream-pop vaguesters A.R. Kane under the joint moniker M/A/R/R/S for “Pump Up the Volume,” they put the needle to the record. To lots of records: Ofra Haza, Trouble Funk, Jimmy Castor, George Kranz, Last Poets, a couple hundred more, supposedly — including at least a few appropriated from Coldcut’s Eric B. and Rakim remix. They topped the pop chart in England, and even got to No. 13 in the States. “Pump Up The Volume” stands as one of history’s all-time how’d-that-happen? hits — but three years later, it didn’t even wind up on the soundtrack of the Christian Slater movie that sampled its name.

The KLF

The White Room (Arista, 1991)

What do you know — another pair of British dudes! Really subversive ones! Or, at least, they thought so. Especially as Timelords (who had a 1988 U.K. No. 1 with their glam-mashup goof “Doctorin’ the Tardis”) and the Justified Ancients of Mu Mu, and as authors of the 1989 self-help book The Manual (How to Have A Number One The Easy Way), Jimmy Cauty and Bill Drummond parlayed ideas allegedly learned from Situationist tracts and Illuminati conspiracy novels into an attempt to upset the music-industry apple cart, even shooting off machine-gun blanks at a BRIT Awards crowd. Totally heavy-handed shtick. But by 1990, Cauty and Drummond were calling themselves the KLF, inventing house music for airports (on the presciently ambient Chill Out), and writing real hit singles. This album spewed up three Top 10s in England and one in the U.S., and they hadn’t even met Tammy Wynette yet; when they later added her to the final track, “Justified and Ancient,” they scored another U.K. No. 2 and U.S. No. 11. Otherwise, they subordinated their slogans to any number of emotion-conjuring soul songbirds and Arabian wailers and dub-ska toasters, and their electropulses are well-built enough to support all sorts of life-forms: MC5 samples, rocket blast-offs, blues and Hawaiian guitar riffs, Radio Free Europe interceptions. In the very Vocodered “Last Train To Transcentral,” they even build their synth riffs into the sort of choo-choo on which the Monkees or Kraftwerk might enjoy being passengers.

Edelweiss

Edelweiss (Gig, 1988)

Here’s the group that justified the Justified Ancients Of Mu Mu’s existence: According to longstanding legend, at least, three Austrian “remixers” with hard-to-pronounce names read The Manual (How to Have A Number One The Easy Way), take notes, then do it. Well, “Bring Me Edelweiss” went No. 1 in Austria, Sweden, Holland, and Switzerland, anyway; but No. 2 in Germany and No. 5 in the U.K. (plus No. 7 on the Dance chart and No. 24 on the Modern Rock chart in the U.S.): Nothing to sneeze at, especially for what’s basically a Alpine gasthaus-house pile-on of Abba’s “S.O.S.,” K.C. and the Sunshine Band’s “That’s The Way I Like It,” Indeep’s “Last Night A D.J. Saved My Life,” “Edelweiss” from The Sound Of Music, and the most blatant yodeling in a hit record since “Hocus Pocus” by Focus. The 12-inch single sleeve showed pictures of accordions, purple cows, buxom, dirndl-wearing milkmaidens, and liner notes to match. And this debut “album” — subtitled A Sound-Attack Straight From The Alps — is somewhat a trip in that, despite containing six discrete and highly entertaining song titles after two “versions” of the hit (“Ruck Zuck,” “Inzest-House,” “Alpenglühn,” etc.), mainly seems to consist of eight versions of the hit, give or take closer “Schnaps Bonus.” Which is a grandmixered cuckoo-clock polka. Or something.

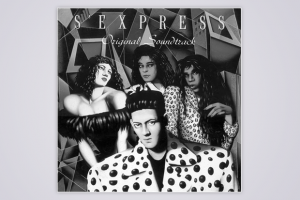

S-Express

Original Soundtrack (Capitol, 1989)

More Brits, more or less expanding on what Brits above had been doing for awhile now, but now deciding that it’s called “acid house” — just like Todd Terry — even if it didn’t sound nearly as toxic as the acid house that guys like Phuture had invented in Chicago a few years before. So, vocalist Michellé (Virgo) gets credited with “microdot clarinet,” for instance. The leader, Mark Moore (Capricorn), is one of two “noise engineers.” “Theme From S-Express,” a British No. 1, is a nighttime train ride across Europe, complete with woofing dogs and table tennis plink-plonks, and Karen Finley talking dirty. Supposedly, Sam the Sham, Gil Scott-Heron, Rose Royce, Stacey Q, Debbie Harry, and Yazoo make appearances as well, though good luck finding them. The locomotive chugs full-speed ahead, regardless. The rest of the album — including subsequent Brit-hits “Superfly Guy” and Sly Stone cover “Hey Music Lover” — is tasteless and generally devoid of personality, populated with porn stars and pimps and monks, but entrancing nonetheless. Album’s “dedicated to homeboy Philip Glass and the Ozone layer”; three years earlier, Colourbox had made a track called “Philip Glass.” Wonder if he heard any of this stuff.

Kon Kan

Move To Move (Atlantic, 1989)

Didn’t take long for sampledelic sounds to congeal into sticky bubblegum, and that’s not a bad thing. This briefly popular Toronto duo, named for the famous “Canadian content” rule wherein radio stations above the border have to devote a certain percentage of their airplay-time to songs by hockey players actually born there, were musical cutie-pies even by synth-pop standards. But that didn’t stop them from melding Lynn Anderson’s ’70s countrypolitan plaint “Rose Garden” with a whole bunch of other stuff (disco tidbits from GQ and Silver Convention and Spagna, an old Marlboro cigarettes theme) into a beauty of a hit (No. 15 U.S. — but only No. 19 Canada!) called “I Beg Your Pardon.” The follow-up single, “Puss N’ Boots/These Boots (Are Made for Walkin’),” shuffled Nancy Sinatra with Led Zep’s “Immigrant Song.” And they even won a Juno Award!

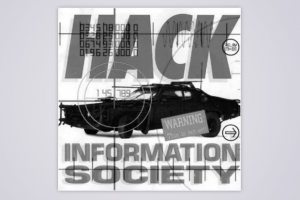

Information Society

Hack (Tommy Boy/Reprise 1990)

And speaking of bubblegum, there was also Information Society. Remember them? Grassroots enough that they put out an early EP on local Minneapolis label Twin/Tone (original home of the Replacements, Soul Asylum, and Babes In Toyland), but probably more enamored with Prince or even Lipps, Inc. than any of that gritty guitar-rock mess, they came off as either American kids who wanted to be British or Midwestern boys who wanted to be Latin freestyle girls. And they pulled it off, to the extent that their self-titled 1988 debut full-length landed two singles in the U.S. pop Top 10. But then they took that success and ran with it, proclaiming “This is not art!” on the cover of their 1990 sophomore set, naming it with a pun that suggested both artless pop-star shills and phone phreaks (or whatever their descendants in the coming, uh, information society might call themselves.) They sampled Rakim, the King Ad-Rock, Kraftwerk, James Brown, industrial muscle-pervs Nitzer Ebb, and Kurt Loder criticizing haircuts; ripped off other sounds and/or words from New Order, Led Zeppelin, and proto-dancehall poet Dillinger’s toasted “Cokane In My Brain”; slipped classical strings, saxes, insurgent mottos, and (speaking of obsolete technology) one VHS mention into the crevices. Flopped commercially, but it had quite the pretty groove to it. Somehow, it seems like they got away with something.