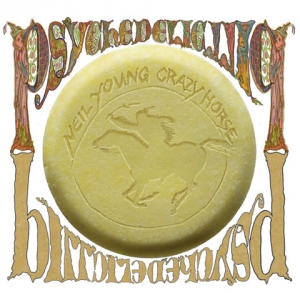

Release Date: October 30, 2012

Label: Reprise

At the heart of Neil Young’s beautifully batshit new memoir, Waging Heavy Peace, is the enduring affirmation that he remains far more impulsive than any rational non-rock-star human could ever conceive of being. Similar (though not very listenable) evidence came earlier this year via Americana, a collection of folk covers of the “She’ll Be Comin’ ‘Round the Mountain” variety played as only Crazy Horse shouldn’t have. Heavy Peace‘s convincing cliffhanger (spoiler alert) speculated on whether Young might ever write a song again. For that reason and more, his new double album Psychedelic Pill is all the more improbable and brilliant.

Not only does Young vividly reprise three or four musical selves here, but he effortlessly invents at least one new one in the process. Flushing songvertisements for Pono (his new audiophile portable music project), lyrics about “hip-hop haircuts,” and general crankiness out of his system during the 27-and-a-half-minute opener “Driftin’ Back,” Psychedelic Pill is as grand an album as he’s made since who-cares-when. Young stomps his way home from the other side of the mirror, dropping meta non-rhymes about his book, a redemptive Harvest-gospel classic, a few slices of nostalgic country, and three remarkably varied Crazy Horse blowouts.

Adopting the opposite persona to Bob Dylan’s late-era southern-gentleman-on-the-skids, Young declares his intention — during a 16-minute closer — to literally “Walk Like a Giant.” As they say, one Pill makes you bigger, and the joy of swallowing it is the joy of rooting for ol’ Shakey as he and his buddies rage against the thinning of the bandwidth, and all the other heartbreak we’re all in for sooner or later. Might as well jam. The results are the most pleasant kind of rambling imaginable. The three long outings — taking up 60 of the album’s 90 minutes — are breathtaking new territory for Young and Crazy Horse, either the most ambitious, multi-sectioned jams they’ve yet attempted or fresh proof that Neil and Frank “Poncho” Sampedro and the gang are far better at improvising forms than they’ve ever previously demonstrated.

“Driftin’ Back” downshifts between guitar grooves like an MC Escher loop, Young and Sempedro circling each other in instinctive, recursive noodle. On “Ramada Inn,” Young pairs earnest Harvest Moon-like heartland ache about a couple in deep middle age with meditative guitar unfurlings. “Walk Like a Giant,” meanwhile, carries the band into a sequence of gnarly solos, two beautifully harmonized bridges, and four minutes of deep Arc destruction that wouldn’t sound out of place at your local DIY noise spot. (Those wanting more would be advised to seek out the Arc 2012 fan compilation.) Each carries a story, even if that story is — in the case of “Driftin’ Back” — about Uncle Neil trying to get those damn mp3s off his lawn. Moreover, each presents a clear and immersive mood, perhaps the album’s heaviest selling point in its fight against the depravities of contemporary shuffle culture.

Everywhere, Young (or perhaps co-producers John Hanlon and Mark Humphreys) also blissfully remembers that Crazy Horse were once Danny and the Memories, a Los Angeles doo-wop trio with a sweet-ass vocal blend. Time has given his longtime compatriots a natural gravitas, and even the half-doofy, self-referential square-dance “Born in Ontario” and the “Like a Hurricane” sequel “She’s Always Dancing” come with a sense of purpose in large part because of, as it were, the Horse’s inimitable smell.

And nestled amid autobiographical twang and a title track with a whooooooshing mix that probably sounds totally bitchin’ on Neil’s own soundsystem, there’s also “For the Love of Man,” the gold-streaked outlier that seals Psychedelic Pill as quintessentially Young. Compressing all of Waging Heavy Peace‘s richest and most idiosyncratic reveries into a lilting carol-like reverence, his long-quivering falsetto enters a new phase of untamed lonesome reverie. It is both effortlessly universal and the best of all possible Neils, joyous and terrified, just like us. In the 21st century, that remains valuable. But so do all the Neils that aren’t like us, products of the last of the wild rock stars, crazed and impulsive and dreaming in Pono.