As I ask Chan Marshall why she would choose to live in Miami, I can hear the italicized sneer in my voice, though it’s unintentional. South Beach’s pastel chintz just seems to bring out a casual, unearned superiority, particularly at this moment between that one guy eating that other guy’s face and the Heat winning an NBA championship, two events viewed with similar disgust by the nation at large.

“But I don’t,” she insists. “I was never here, and I was never in New York, either — I’d only be off tour four days, seven maximum. You don’t live anywhere.”

I think what I mean, though, is that she’s always seemed part of something bigger. Though she is from Georgia, moved frequently as a child, and doesn’t have a sound that connotes any particular place or scene, she has felt central to ’90s indie-boom New York, as typified by her label Matador Records, where only Yo La Tengo and Stephen Malkmus rival her for seniority. Miami just seems so…not that. But as I ride a cruiser bike along its esplanade, a few feet behind Marshall, searingly hungover and armed with a bag full of empanadas, I find it easy enough to understand the city’s charms. She takes a photo of a bike chained to a tree; its model name is Sun.

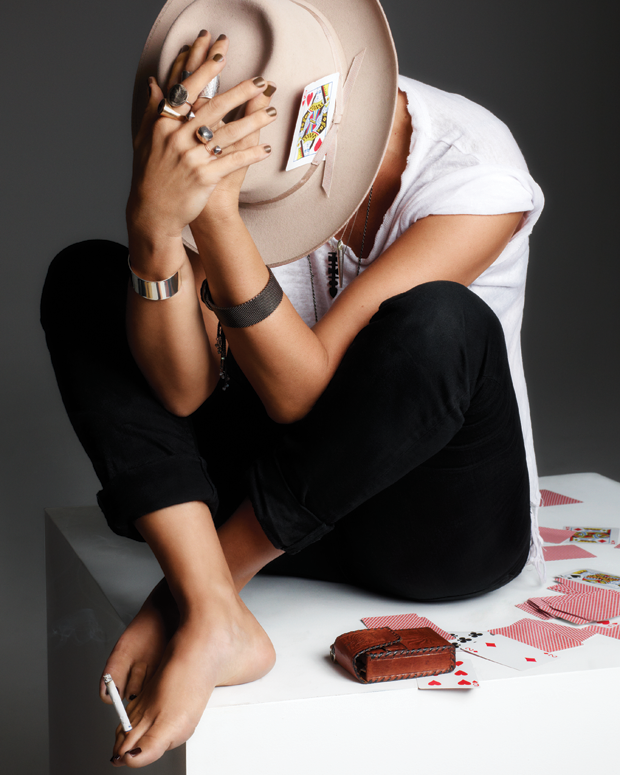

“Well, there’s no community anymore because everybody grew up,” she says, now sitting on the beach with her arms around her knees, Camel Light between her fingers. (“All the friends we used to know ain’t comin’ back,” she laments in Sun‘s chiming “Manhattan.”) “I do miss going to shows. I miss seeing the Make-Up, seeing Ian [Svenonius] hanging from the rafters. I miss seeing the Jesus Lizard. I think the hardest thing about my life is that I’ve met so many people all over the world who I love, but they’re not friends with each other. I’ve never had a clique. It’s impossible when you’re always traveling. Even when I was little, I was always going to a new school, and my parents would be ready to leave just when I’d made a best friend. And I think that’s why I’ve suffered in domestic relationships, because it means everything to me.”

The beach is bustling with families and dogs and people flying kites. The water is emerald, the sand is bone-white, and I am trying superhard not to dry-heave into a paper bag. “There’s nothing but men here,” she says, looking across the expanse of beach. She counts 12 women and 29 guys in her peripheral vision. “They’re all having fun, dude. It’s a Tuesday.” Three dogs. And one elephant.

As many times as she brings up her relationship and its role in the past half-decade of her life, she never acknowledges Ribisi by name. They only broke up a couple of months ago, and she’s still raw — as we wheeled the bikes out of her storage room, she pointed out the boxes of her stuff that were waiting for her when she got back to Miami.

“A lot of people were angry,” she says. “Or not angry, just fearful that I wouldn’t ever turn in a record or that it would be bad. But I was having a steady relationship, living in one place for a long time, and I’ve never done that. There were things I was learning about myself from that, you know? My identity within a new family structure, learning about a whole other life, separate from making songs up.”

And this is where I mention that there had been whispers that she’d gotten into Scientology, since Ribisi and his family are highly prominent members, and maybe the church had something to do with her prolonged absence, and for a moment, all the oxygen seems to vanish from Miami Beach.

“I wouldn’t know. I’m not a Scientologist,” she says brusquely, but not impolitely. “And I never have been.”

“Right, but knowing how active he and his — “

“My friends know I wasn’t [involved with] that. People and their religions don’t affect me. I was having a relationship with one person. My last relationship before that was with a Southern Baptist; his grandfather was a minister in North Georgia. Some families have religion and some don’t. You’re searching for something. What is it you want me to say?”

I tell her I’m not trying to get her to say anything and ramble on, explaining that the public perception of Scientologists is acutely different from that of Southern Baptists, especially as it relates to the creative class and famous people. For every celebrity who speaks openly of an association with Scientology, such as Beck — Ribisi’s brother-in-law — others honor the organization’s well-cultivated shadowiness. It’s not a stretch to speculate that Marshall, who has been frank about her psychological struggles, might have backed away from a music career because her boyfriend was involved with a highly secretive group whose staunch antitherapy stance rates among its few widely known tenets.

“Well, it’s new,” she says. “Our religious culture is based on shit that’s been talked about for hundreds of years. But this, nobody fuckin’ knows about it. But I’m a very accepting person, so I don’t really care, so long as you’re not telling me I’m going to burn in hell unless I do this or that.”

“Are you mad at me?”

“Naw, inquiring minds want to know.”

Which is not to say that Sun was an easy record to make, or lacked drama. She played an early demo for a trusted confidant — “I can’t say whom, I’ll hurt someone’s feelings” — whose reaction was just withering enough to crush her momentum. “I’ve never played songs like that for anyone before, and he thought the songs were too slow. I was really devastated and didn’t do anything else for, like, eight months.”

But from that tailspin came a resolve to do things differently. She booked studio time in Los Angeles so she could write in earnest, rather than hope her tape recorder at home had batteries whenever the muse struck. A turning point came when she heard the Beastie Boys’ Hot Sauce Committee Part Two, and she arranged to meet Philippe Zdar, who mixed that record, in Paris to play him the new demos.

“The songs sounded pretty much the way they do now,” says Zdar, who considered Marshall’s lack of familiarity with the tools of production to be an asset as he helped her piece the bits together into songs over nine months in France. “There was a naïveté, but also a genuineness. She’s true. She doesn’t try to seduce you.”

This story originally ran in SPIN’s September/October 2012 issue — order yours here now!