Conservative columnist David Brooks is just smart enough to get by. He’s armed with hubris that allows him to wander out of his house and fit whatever he sees into an already formed thesis that sounds pretty reasonable if you don’t think about it too hard. Yesterday’s column by Brooks, a wide-eyed, close-minded Stanley Crouch rip-off called “The Power of the Particular,” is ostensibly about seeing Bruce Springsteen in Spain and France. But woah, man, you know all those foreigners over there in Europe? Well, despite not being born in the U.S.A., they somehow manage to relate to the Boss’ distinctly American/New Jersey sensibility because it’s just so authentic and real, and, why, that got David Brooks thinking about how pandering politicians and bantering business fucks reaching for universality have just got it all wrong.

Isn’t David Brooks, a supposed conservative, just as superficially out-of-place at a Springsteen concert as an arena full of Europeans? Never mind all that, his insight really seems aimed at Mitt Romney, whose Wawa(s) boner last week was particularly transparent: “The whole experience makes me want to pull aside politicians and business leaders and maybe everyone else and offer some pious advice: Don’t try to be everyman. Don’t pretend you’re a member of every community you visit. Don’t try to be citizens of some artificial globalized community. Go deeper into your own tradition. Call more upon the geography of your own past. Be distinct and credible. People will come.”

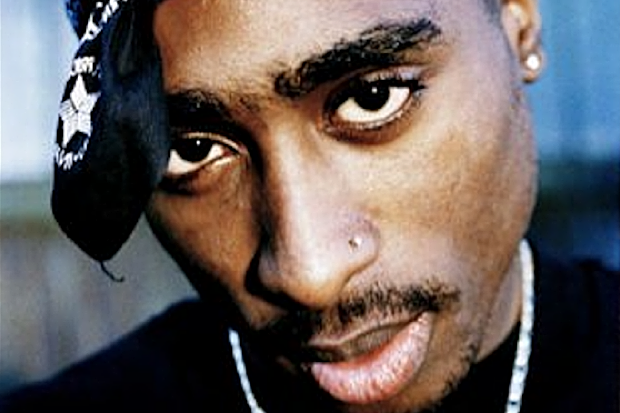

Along with Springsteen, Brooks suggests some other non-everyman, global community-rejecting practitioners such as J.K. Rowling, Evelyn Waugh, the guy(s) who created Downton Abbey, and Tupac Shakur. This is classic David Brooks rhetoric. Unlike his completely clueless, right-leaning buddies, Brooks has some pretense towards inclusiveness and, so, he makes sure to crowbar in that hip-hop reference. And as is often the case with Brooks, when he tries being hip and with-it, this “public intellectual” ends up showing his ass (like when he famously said Barack Obama “doesn’t seem like a guy who can go into an Applebee’s salad bar”; Applebee’s don’t have salad bars).

Also Read

SAME AS THE OLD BOSS

Brooks cites Tupac’s milieu as “Compton” — that’s to say, in David Brooks’ insular editorial-page world, Tupac is to Compton what Springsteen is to Asbury Park, N.J. — which, of course, is blatantly incorrect. The late rapper was born in Harlem, spent some time in Baltimore, moved to Marin City, California, in 1988, and when not simply reduced to a “West Coast rapper,” is generally associated with the Oakland area. And as any number of people trying to make a case for Tupac’s bigger-than-hip-hop respectability will mention, he was raised by a mother who was in the Black Panthers, was a theater student who performed Shakespeare, and a poet. The monolithic, world-renowned rapper contained multitudes and he brought those multitudes to a public who could relate, not because he was some raw uncooked product of a single city or environment (an assumption just as absurd to pin on Springsteen), but because his music could appeal to many different people for many different reasons.

This isn’t just rap-nerd nitpicking, either, because Brooks’ use of Tupac (and his whopper Compton gaffe) illustrates the problem with Brooks’ thesis altogether. There is nothing “particular” about rock music. It is a mutt mix of blues, folk, country, jazz, and many more styles. The power of “Born in the U.S.A.” or Tupac’s “Brenda’s Got a Baby” is not their particularity, but the way that these artists swirl around dozens of particulars, leaving room for a variety of ways to penetrate their work. Brooks’ essay couches a dangerous argument against cross-cultural exchange and a sly rejection of multiculturalism. Springsteen and Tupac would still exist if they believed that “global communities” were “artificial.” Their music was formed by a confluence of particularities.