[EDITOR’S NOTE, February 2, 2010: Because the White Stripes announced today that they are officially disbanding, we are republishing Chuck Klosterman’s first interview with the band, which originally appeared in SPIN’s October 2002 issue.]

Jack White flicks his cigarette ash into a glass of water. He and Meg White are sitting on a couch in an überswanky hotel room in downtown Chicago, trying to explain how it feels to be a punkish underground band — with modest sales and an antimedia aesthetic — that has somehow become America’s most frothed-over rock group.

“We’re in a weird spot right now,” Jack says. “To be honest, I have a hard time finding a reason to be on the cover of SPIN. It was like being on the MTV Movie Awards [where they performed their recent single ‘Fell in Love With a Girl’]. You start asking yourself, ‘What are we getting from this? What are we destroying by doing this? Does it mean anything?’ So you try it. You wonder if you’ll end up being any different than everyone else, and usually, the answer is no.”

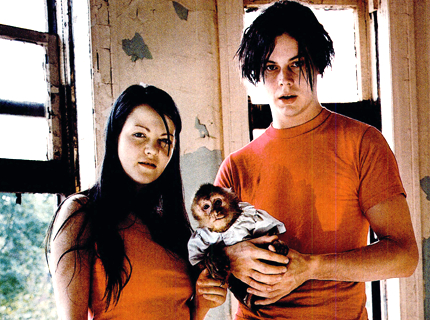

Actually, the answer is yes. The White Stripes are different. If you ignored their songs, you’d assume they were a novelty act: They wear only matching red, white, and black clothing, they have no bassist, and they’ve built their public persona around a fabricated relationship (they claim to be siblings, but they’re actually an ex-couple whose divorce was finalized in 2000; see sidebar). But there is no punch line. Mixing junk punk and tangled roots music, singing some of the most complex love songs since Liz Phair’s heyday, the White Stripes have done what great rock bands are supposed to do — they’ve reinvented the blues with contemporary instincts. They represent a sound (postmodern garage rock) from a specific place (downtown Detroit), and it’s a fascinating mix of sonic realness and media boondoggle.

As we talk, guitarist Jack speaks in full, articulate paragraphs. Drummer Meg mostly hugs a pillow and curls her legs underneath her body, hiding feet covered by rainbow-colored socks that resemble Fruit Stripe gum’s zebra mascot. The night before, the duo played the Metro club near Wrigley Field, and it was an acceptable 90-minute show. However, tonight they’ll play a blistering set at the Metro that won’t start until 12:55 A.M., and it will annihilate the molecules of Illinois’ air: They will do an extended version of a new song (“Ball and Biscuit”) that makes references to being a seventh son and includes a grinding guitar solo that’s shredded over the beat from Queen’s “We Will Rock You.” They’ll cover the Animals’ “House of the Rising Sun.”

Everything is raw and unrehearsed and imperfect. And that’s why it’s so fucking good.

“We have to go back,” Jack insists. “The last twenty years have been filled with digital, technological crap that’s taken the soul out of music. The technological metronome of the United States is obsessed with progress, so now you have all these gearheads who want to lay down three thousand tracks in their living room. That wasn’t the point.”

“The point,” says Meg, “is being a live band.”

Perhaps Meg is right. However, classifying the White Stripes as two kids in a stellar live band in no way describes their curious career arc and often contradictory aesthetic. Supposedly formed on Bastille Day in 1997, they got some attention for being bass-less and dressing like pieces of candy. After they’d released two albums (1999’s eponymous debut and 2000’s De Stijl, named after a Dutch art movement that emphasized primal abstraction) and toured with Pavement and Sleater-Kinney, there was a growing suspicion that Jack and Meg were succeeding where Jon Spencer and his cheeky Blues Explosion had failed — there is no irony to what the Stripes create. “We wanted things to be as childish as possible, but with no sense of humor,” Jack explains, “because that’s how children think.” Children also fib, conflating truth and fiction, real and fake, for the mere fun of it.

Like Pavement in ’92, the Stripes brought romance and mystery to an indie underground devoid of rock’n’roll fantasy. By the release of White Blood Cells in the summer of 2001, they’d evolved into a cultural phenomenon. Eventually, they signed a lucrative deal with V2 (which has since rereleased their earlier albums), had their own Lego-centric MTV hit, and were embraced by modern-rock radio programmers looking for a post-Bizkit hangover cure.

V2 President Andy Gershon, who reportedly signed the band for $15 million, was reluctant at first. “Your conventional wisdom is that they’re a two-piece, they need a bass player, they’ve got this red-and-white gimmick, and the songs are fantastic, but they’re recorded very raw…how is this going to be on radio?” he says. “But for me, it was like, the record’s amazing.”

Along with the Strokes and the Hives, the White Stripes are part of a back-to-basics real-rock revival awkwardly termed “neo-garage.” With roots in the ’60s stomp of teenage bands responding to the British invasion, “garage rock” is all about simple, direct catharsis. For years, the music was the province of aging coolsters, but neo-garage infuses that old sound with glammy magic.

The White Stripes are from Southwest Detroit, more specifically from a lower-middle-class Hispanic section uncomfortably referred to as Mexicantown. They claim to be the youngest offspring in a family of ten children. They claim to have formed one day when Meg wandered into their parents’ attic and began playing Jack’s drum kit. This is certainly not true. This much is true: Mexicantown is where Jack White grew up and operated an upholstery shop, and Meg is from the same ZIP code; she once worked as a bartender at a blues bar in the trendy northern Detroit suburb of Royal Oak. Jack is 26. Meg is 27. The White Stripes are “Detroit people,” and they are the most visible band in the Detroit garage-rock scene, a conglomeration of pals extending far beyond the Stripes themselves.

Detroit is full of underproduced, wonderfully primitive rock bands, all playing the same bar circuit. You could waste a weekend trying to name every band in the 313 area code (a lot of them are on the Sympathetic Sounds of Detroit compilation, which Jack White recorded in his living room). There are the Von Bondies, a sloppy, MC5-ish rave-up quartet, and the Clone Defects, an arty, quasi-metal band. Slumber Party are borderline shoegazers; the Come Ons play trad ’60s-ish pop. The Dirtbombs bridge the gap between glam, Detroit’s Motown past, and the blues-rock future. The Piranhas are a destructo-punk band, already local legends for their “Rat Show” at a now-defunct club called the Gold Dollar in 1999 (their singer performed with a bloody, freshly executed rat duct-taped to his naked torso). The Detroit Cobras are the hottest band of the moment(supposedly ignoring an avalanche of major labels trying to sign them).

But the White Stripes are the conflicted media darlings. Unlike most of their blue-collar peers, they have a well-cultivated look, an artistic sensibility, and a mythology, which makes the Stripes an idea as much as a band (almost like a garage-rock Kiss). But the real reason they’re the biggest little rock group since Sonic Youth is impossible to quantify: Audiences hear something in their music that’s so fundamental, it almost feels alien.

According to Jack, what they’re hearing is truth.

“We grew up in the late ’80s and ’90s, and what was good in rock’n’roll for those 20 years? Nothing, really. I guess I liked Nirvana,” White says. “And sometimes when you grow up around all these people who only listen to hip-hop, something inside of you just doesn’t connect with that. Some people will just kind of fall into that culture — you know, white people pretending to be black people or whatever — because they’re involved in an environment where they want to fit in and they want to have friends, so they decide to like what everyone else likes and to dress how everyone else dresses. Meg and I never went along with it.”

I try to get Meg to comment; she defers to Jack, smiles, and looks away. Meg seems really, really nice and really, really bored. She and Jack laugh at each other’s jokes, but they mostly behave like coworkers. I ask her how she feels about the way people have portrayed her — like when reporters infer profound metaphorical insight from her unwillingness to chat.

Wendy Case is less shy than Meg White. In fact, Wendy Case is less shy than David Lee Roth. She is the 38-year-old lead singer/guitarist for the Paybacks, a band Case describes as “hard pop.” Her hair is blonde on top and brown underneath, she laughs like a ’73 Plymouth Scamp that refuses to turn over, and she can probably outdrink 90 percent of the men in Michigan. We are riding in her black Cherokee down Detroit’s Cass Corridor.

“If you’re gonna look for one unifying force [in the Detroit scene], the thing is that we all still drink,” Case says. “You get together and you drink beer, and you listen to music. That’s pretty much the nucleus of every social situation.”

The Cass Corridor is a strip of urban wretchedness jammed between the north shadow of Detroit’s skyline and Wayne State University. It’s basically a slum, filled with dive bars and homeless people who spend afternoons having animated conversations with the heavens. This is where Detroit’s garage rock has flourished, so it’s no surprise that most of this town’s bands are no-nonsense buzz saws. But the depth and intensity of their musical knowledge is surprising. The recent Dirtbombs album, Ultraglide in Black, is mostly covers (Stevie Wonder, Phil Lynott), and the Detroit Cobras’ Life, Love and Leaving is all covers.

“We’ll all sit around and listen to an old Supremes record or a Martha Reeves and the Vandellas record and marvel at the production level, especially considering how cheaply it was done,” says Eddie Harsch, a guy who used to play keyboards with the Black Crowes and currently plays bass for the Cobras. “People in Detroit know their records.”

This is true for the Stripes, who pepper shows with Dolly Parton’s “Jolene,” Meg’s rendition of Loretta Lynn’s “Rated X,” and the menacing, tommy-gun riff of Link Wray’s “Jack the Ripper.”

Explains Jack: “We’ve never covered a song simply because it would be cool or because we’d seem really obscure for doing so. Certain circles of musicians will all get involved with the same record at the same time and suddenly it will be cool to like the Kinks’ Village Green Preservation Society for a month. But why didn’t people feel that way three years ago? I’ve always hated the whole idea of record collectors who are obsessed with how obscure something is. Usually when somebody brings up something obscure, I assume it’s not very good, because — if it was — I would have heard it already. Record collectors are collecting. They’re not really listening to music.”

We talk a little longer. Then Jack does something odd. He reaches behind his waist and rips the tag off his black pants. It’s the type of weird moment that makes the Stripes so baffling and compelling. In and of itself, it’s not mind-blowing that a guy ripped the tag off his pants. But this small, theatrical gesture punctuates Jack’s quote better than words ever could. It looks rehearsed, even though that’s impossible (it’s hard to imagine Jack buys a new pair of trousers for every interview). Yet everything the White Stripes do raises a question. How can two media-savvy kids posing as brother and sister, wearing Dr. Seuss clothes, represent blood-and-bones Detroit, a city whose greatest resource is asphalt?

“One time I was joking around with Jack,” recalls Detroit Cobras guitarist Maribel Restrepo, who lives ten minutes from where Jack resides in southwest Detroit. “And I said, ‘If you tell little white lies, they’ll only lead to more lies.’ And he goes, You can’t even do that, because the minute you say anything, that’s all people will talk about. It gets to where you don’t want to say anything.'”

It’s not that less is more; it’s that less is everything. When Meg White hugs her pillow and tells me that people put more thought into shyness than necessary, I want to play along with her — even though she’s totally lying. It’s as if we don’t want to know the truth about the White Stripes. The lies are so much fun.