Despite an exorbitant budget, decades-long production history, prestige casting, and the involvement of a couple of the most famous entertainers of the past 50 years, HBO’s Vinyl was canceled earlier this week after a single season. The development was unexpected but not surprising — Vinyl debuted to lackluster ratings and underwhelming critical notices, and leaked buzz over the course of a rocky first run. Simply put, Vinyl was a failure: Its characters were unlikeable, its plotting was predictable, its drug usage was cartoonish to the point of actually being boring. The relationship between protagonist Richie Finestra (Bobby Canavale) and wife Devon (Olivia Wilde) went so bad so quickly that you had no reason to root for it to survive, and Richie made so many inexcusable decisions as head of the fictional American Century Records that you prayed they’d blow the label’s entire budget on Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music. It wasn’t a good show.

But that didn’t have to be a death sentence for Vinyl. TV shows don’t need to be good if they’re fun, and there is no quicker way to a fun TV show set in the music world than by having awesome fictional songs — as Empire and Nashville, two other gratifying industry dramas with soap-operatic scripting and sporadically reactionary politics, have proven. Weak character development, lackluster storytelling, and anachronistic ideas about Important Television are all totally forgivable if the show actually kinda rocks. And that, ultimately, was Vinyl‘s most unforgivable sin: Its music sucked, too.

The biggest issue came with the show’s central musical group, the Nasty Bits. The band was supposed to be Vinyl‘s Sex Pistols, or at least its New York Dolls — the act that comes along when rock excess is at its most bloated and self-satisfied and shocks everyone into actually giving a f**k again. But the show could never decide whether it wanted the Nasty Bits to be true punks, punks with hearts of gold, or just punks until a better opportunity came along, and the actors (led by James Jagger, son of Mick, as the band’s perma-snarling frontman) seemed just as confused as we were watching them. Events paired the band with Lester Grimes, an older, blues singer and ex-buddy of Richie’s, in an absurd reach to keep a core character close to the action while simultaneously proving that All Music Is Just Music, and the song that results from his mentorship — a cover of Grimes’ unreleased 12-bar jam “Woman Like You” — is about as blistering and urgent as a Jet single.

Other artists fared little better. Ray Romano’s record-man character Zak discovers Gary, a young piano player performing “Life on Mars?” at Zak’s daughter’s Bat Mitzvah, and hopes he can turn the enigmatic singer into the next David Bowie. But from his performances — one of which he breaks out during his contract signing at a crowded restaurant — it’s impossible to tell if the kid is supposed to be a legitimately impressive new talent, or just an awkward wedding singer that the insecure Zak has deluded himself into thinking is special. Funk shaman Hannibal — a P-Funkier Sly Stone in Vinyl‘s world — is a more convincing live performer, but a less convincing force of personality, and his best songs never raise above the level of plausible pastiche. For a show that’s supposed to remind you of the greatness of rock’n’roll, it’s telling that the only truly memorable fake song from Vinyl‘s ten-episode run was the depressing Robert Goulet Christmas ballad that American Century tries to talk him out of recording — yet another example of these characters’ (and this show’s) critical lack of discerning musical supervision.

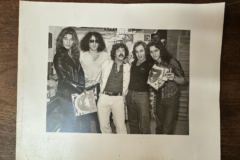

The real disappointment here is that Vinyl wasn’t without its musical spark — it’s just that it only flickered when the show interacted with lightly fictionalized versions of IRL music history. When Richie meets with Led Zeppelin backstage at Madison Square Garden in the pilot to discuss their contract, and Robert Plant is revealed through his interaction with Finestra to be the 1975 equivalent of Matty Healy from the 1975, it makes you realize, Wow, I never even considered what this super-famous rock legend was actually like as a young person. When Alice Cooper takes a naive young exec golfing and then pretends to execute him with his fake guillotine, you get the unmistakable urge to listen to Billion Dollar Babies for the first time in years. And when Richie meets with Fat Elvis in his Las Vegas hotel room and comes right to the precipice of convincing the King to make a run at recapturing his crown — before being thwarted at the last second by a malice-oozing Colonel Tom Parker — you’re actually crushed that he couldn’t get it over the goal line. But the electricity of these scenes only served to emphasize how much the rest of the show flatlined.

Considering the near-unprecedented financial resources invested in making Vinyl a success, you’d think that maybe HBO could have invested more in the fictional songwriting and artist development department — the fact that a Google search for “Adam Schlesinger Vinyl” returns nothing of consequence suggests they certainly could have tried harder. Or maybe they should have cut out the fake artists altogether and focused on alternate-history interactions with real-life artists like those listed above, however much more that would have cost. But bottom line: If you’re gonna make a show centered around the days when it used to be about the power of music, maaaaan, make sure the music is goddamn powerful. Otherwise, no one’s gonna put the needle back on the record.